Don’t Fear Your Meters (How to Gain Stage the Mix)

If there’s a topic that will get rabid audio fans to their feet, it has to be metering and reference levels, am I right?

If there’s a topic that will get rabid audio fans to their feet, it has to be metering and reference levels, am I right?

I will acknowledge that it’s not as glamorous or sensational a subject as some, but there’s a reason that meters are still with us after all these years.

In the most basic sense, meters are there because we can’t physically see or count the electrons traveling through the console or compressor or mic pre, so we can’t know how far above or below the optimal signal level we are with any certainty.

But despite their ubiquity, I feel like the true usefulness of a good audio meter is often overlooked. And not all meters were created equal.

I would wager that most musicians, producers, mixers and engineers don’t think much about their metering, and about the correlation between what a meter is trying to tell them and the reference level at which they’re working.

I also suspect that I could safely place another wager that most of them really don’t care what reference level they’re working at, which is fair.

But just because most people don’t think much about their metering or reference levels doesn’t negate the fact that there is much to gain by thinking just a little bit more about yours.

Why Bother Talking About Meters, Anyway?

After your ears, your meters can tell you more about your mix than any other tool. And different types of meters can help lead you to different decisions.

When I started developing my skills in audio way back in 1987

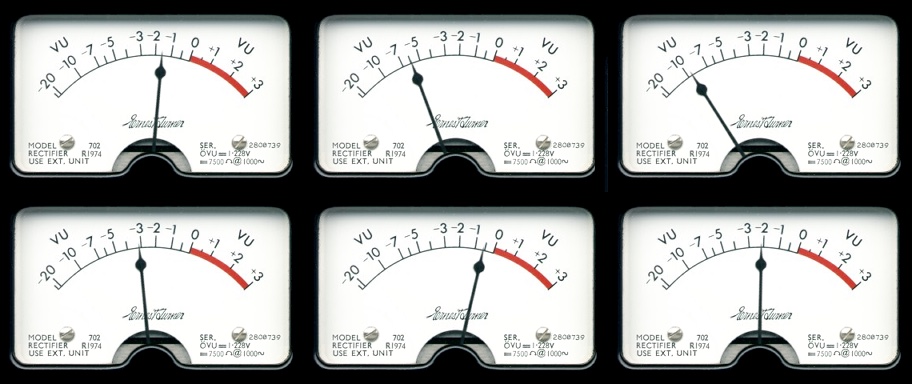

VU (Volume Unit) meters were standard on tape machines and on the main outs of the console.

Back then, the LED ladders and bar graph meters, which are now so common today, were usually limited to “newer” compressors and effects devices.

The same was true in the live sound world: The input meters were often LED ladders, or in simpler arrangements, a “signal” and “peak” indicator which let you know that each channel was passing signal and was not clipping at the input stage. The trusty console output VUs, however, were there to tell you what was really happening, as LEDs weren’t (and often still aren’t) a very good indicator of overall volume or RMS levels.

As consoles got smaller and cheaper, the need for compact metering became essential. Soon, only the most expensive, large-format consoles would include a pair of VUs on the main stereo buss.

The first time I ran a small show on a 16-channel mixer with nothing but LED metering, I found that it was not easy to know exactly how hard I was really driving the system on average, aside from listening for how loud it was, of course. Having grown accustomed to using VU meters, I was a bit out of sorts.

In my years of doing live sound, I learned early on that knowing a sound system’s optimal level and absolute limitations are key to getting great results out of the PA.

If a sound system has been properly aligned and gain-staged, you can keep your average levels around 0VU and you will usually be in good shape throughout the entire signal path. By doing this, you could generally ensure that you would have minimal noise and more-than-adequate headroom to keep things clean—even with large transient changes.

Could I just use my ears? Sure, why not. Ears are a remarkable at discerning tiny changes and differences in a way that meters don’t always bear out. But our ears also tend to prefer “louder” and “brighter” (especially when directly comparing options in the short term) so they are not the most objective instruments. Meters, on the other hand, are completely objective and absolute.

If you use meters deliberately to help make better decisions about how to make things sound good then you’re much more likely to consistently deliver excellent results.

In the end, using meters isn’t about trying to stay strictly within the boundaries. Rather, it’s about clearly defining where those boundaries are so you can comfortably brush up against them.

Gain Structure in Consoles

The best way to understand how metering works in the digital domain is to first understand how it works in the analog world.

Recording consoles—and all other analog audio devices for that matter—are designed so that when you use them properly, you can maximize the signal-to-noise ratio while keeping distortion low or non-existent.

Console manufacturers try their best to provide a roadmap by clearly labeling the faders and pots, and calibrating the meters to specific standards.

All audio circuits have a “noise floor”—the operating noise of the electronics even when no signal is passing through them— that serves as the lower boundary for their dynamic range. They also have a “maximum output level”—which is often qualified with a distortion percentage, expressed as a percentage of “Total Harmonic Distortion (or THD) within a certain set of parameters.

Faders generally have a “unity gain” marking to give you a starting point for a kind of operational sweet spot. By setting the fader at unity gain, you can then dial in the amount of input gain needed for a particular source. When setting the input gain, if I set my average levels to be around 0VU, then unless an extreme peak comes through, I should have a mostly clean, robust, low-noise, distortion-free track.

On a professional analog console or piece of gear, a signal at 0VU normally leaves about 20dB of headroom before audible clipping. It should also leave the noise floor far below—usually between -72dB and -90dB, depending on the quality of the piece of gear, the number of channels engaged and so on.

20dB above 0VU is actually a ton of headroom for a single input. But when you consider this headroom across a full mix and the transient nature of most music, that 20dB can quickly disappear, or at least seem closer than it appears in your rear-view mirror.

To add to the precariousness of balancing and policing levels in a dense mix, an analog console’s summing amps are located before the master fader. If you happen to be slamming the output meters and think you can remedy the problem by bringing the master fader down? Sorry, you’re out of luck. Anything that exceeds the maximum output level is likely clipping the summing amps as well. The only way to fix this problem is to bring all of the faders down a proportionate amount.

This differs from Pro Tools today, where bringing a master fader down actually lowers the operating level of the corresponding bus, thus eliminating the headroom problem. Since modern DAWs have an almost unlimited amount of effective internal headroom—especially in today’s world of 32-bit floating point processing—the concept of “running out of headroom” in a digital mix may seem peculiar or foreign to newer mixers, but I assure you it exists!

Tape is the Same…But Different

The behavior of an analog tape machine is similar to any other analog circuit, except at the extremes.

The noise floor of good, professional, virgin tape is around -68dB, though print-through can make the practical figure more like -56dB (as per ATR Tape).

At the top end of the scale however, the output level at 3% THD (Total Harmonic Distortion) is +12dB.

This means you have about half as much headroom above 0VU with tape as you do on a good analog console. That would seem like a problem on its face…because why would you want to lose headroom? Dynamics are important in music, right?

But tape, being the sneaky bugger that is, is not a linear medium, unlike so many audio circuits. Tape compression, which occurs as you exceed 0VU is very gentle and pleasant sounding. In fact, analog tape is so good at setting compression thresholds and ratios that we hardly notice it. This is because tape responds gradually and dynamically to changing levels in a sonically pleasing way.

To add to tape’s versatility beyond compression, the signal will gradually transition into saturation as you drive the tape harder. And this saturation sounds quite good if used on certain sources with some discretion (transformer-coupled circuits can behave like this too).

All of these factors contribute to tape’s revered “warmth”, and will make an otherwise perfectly reasonable person say, “it sounds like a record” when they track to tape. It’s almost as if the tape machine becomes your skilled, astute, invisible virtual assistant, who perfectly processes your audio before the first playback.

Contrast that with a typical solid-state analog circuit, which goes from clean to dirty in an instant and you can see how that this “loss” of headroom is now a benefit.

Rather than abruptly clipping signals that contain large peaks (like what happens on a console) you are treated to smooth compression and pleasant harmonic distortion, leaving your tracks, thicker, smoother, and easier to deal with. When you apply this effect across a bunch of tracks you end up with a more consistent average level, too.

Once upon a time, this was just part of the everyday process of recording, because tape was the only available format. Once digital became the de facto standard, I had to adapt my analog-centric workflow to deal with the change in tone, dynamics, and noise. It took a period of trial and error to feel comfortable again, but at least I was still mixing on a console with my reassuring VU meters starting back at me.

From Then to Now

The transition from mixing on a console to mixing in-the-box, did not go quite so well for me at first. To be honest, it was a mess.

My monitoring was good. Creating complex routing schemes in my DAW was far easier than with analog. There were virtually unlimited channels available and I had plenty of plugins available.

But despite all that luxury, every mix had become a bit of a crapshoot. The balances were fine, but I always felt like I had no idea of how each mix would interface with the outside world. In addition, I also was not consistently driving my compressors the way I wanted to. The thresholds and gain structure seemed a bit off from what I expected.

Mastering was even worse. Without my trusty analog VU meters, the only way I could ensure my masters were loud enough was to directly compare my average levels with other commercial releases by ear. This was not ideal.

Mixing on a console had been so easy for me in the past. Everything made sense, and the gain structure was basically the same for every mix. When I would patch in a compressor, it lined up as expected, and setting the threshold was a breeze. “0” had meaning across the whole system. But in my DAW, there was no longer any such standard.

What had changed? You guessed it…no VU meters!

This experience taught me that using VU meters was a bigger part of my workflow than I had realized. On a VU-equipped console, I could use the meters to set things up at the start of the mix to ensure that I maintained adequate headroom on the stereo bus at the end. In other words, I used the meters at the beginning and I used the meters at the end; the rest of the time, I was just mixing.

In the box, I was still “just mixing”, but the ending wasn’t always so happy. Keeping the mix bus out of the red was pretty simple, but aiming for some kind of consistent RMS level became a stab in the dark. The ballistics of the stock DAW meters at the time were not very good at displaying average levels, so they were not particularly useful.

Clearly, if I wanted to improve my in-the-box mix process, I needed better metering and I needed a new reference point.

Improving Metering in the Digital Domain?

Deciding on a new digital reference level took some research, forethought and discussion with trusted colleagues. A defining moment in my quest for better digital metering came after a mix project in 2006.

It was the first time I had elected to print my final mixes back into Pro Tools instead of printing to ½” tape, and it was a real eye-opener.

After some discussion with the mastering engineer, I decided to set my console’s 0VU point to -18dBfs, which is still a common reference point today. This means that 0VU on my console would correspond with -18dBFS on Pro Tool’s digital scale, about 1/3 or so down from the top of the digital meter.

My thinking was that there would be little chance of any digital “overs” this way, and the console output would be captured accurately and transparently. I completed the mixes and the band and I were very happy with the way everything sounded.

On this particular record, another mixer was going to mix two of the songs, so the mastering engineer would now have to deal with two different types of mixes, mixers and reference levels. No big deal.

While my mixes were printed at the wide-open, super-dynamic -18dBfs reference, the other mixer had printed his, way, way louder…somewhere around -8dBfs! The other guy’s mixes were already as loud as the final master ended up being, but mine were nowhere near that level. The mastering engineer had to add a bunch of extra level to mine and take a bit away from the other guy’s mixes as he ran them through his chain, but all in all, it turned out well.

Knowing what he had to do to bring my mixes up, and considering what may have been lost by having to reduce the other mixer’s tracks caused me to re-think this whole reference level business: If I printed too hot, then the mastering engineer would have nowhere to go but down. If I printed too low, then he might have to add a bunch of level to drive his signal path properly, which could potentially add some noise.

I wanted to find a good middle ground that would approximate the RMS level of ½” tape while still giving the mastering engineer a little room to do what needs to be done.

Taking matters into his own hands, the author built his own VU meter box for his DAW. Today, similar solutions are available in the box as well.

First thing to address: Get some good meters, and preferably, some VU meters.

I had a friend design a meter drive circuit that I could run off my audio interface. I then purchased a used pair of VU meters from an old MCI console.

I got a project box, bought some components, stuffed and soldered them into a breadboard, installed the meters and input jacks, and voila! I had a VU meter box.

My circuit-designer friend made sure that there were trimmers on the circuit to allow me to align them to a chosen reference. So naturally…I had to determine an ideal reference point for 0VU on my own.

Based on my tape analogy (pun intended), using a reference level of -12dBfs would give me exactly 12 dB of headroom before I hit digital full scale (0dbs) and risked hard clipping.

This reasonably approximates the general level of headroom that tape affords, but doesn’t really account for the transients that would exceed a good tape machine’s “3% THD @ +12dBVU” spec. Tape tends to forgive such ills as an occasional peak, and they often pass by without being noticed.

But digital does not possess this same forgiving tendency, and when presented with too much signal it gives you back lovely, flat-top waveforms. This was not acceptable.

With all of this to consider, I decided on a 0VU reference level of -14dBfs and have never looked back. It gives me enough headroom to not have to beat transients into submission—though I must always be mindful and proactive to keep them in check. By using this reference level, I have a nice, healthy amount of RMS (average) level on every mix, and 14dB of available headroom before digital clipping to maintain some transient dynamics.

Some mixers go even further by calibrating their monitors to a specific reference level in terms of SPL. For instance, if you were to calibrate your speakers to put out 80dB or 85dB of sound pressure level in your mix room when you hit 0VU with broadband signal, you could know just how low loud your mixes sound and feel compared to others without ever having to pull up a reference track.

Zero, My Hero

This is where a full understanding of how these analog devices absorb a signal is so important. The snare, the lead vocal, a big tom hit, bass drops and the like can all cause pain and clipping on the stereo bus, so I had to figure out ways to deal with them while maintaining my overall average levels.

By using plugins that simulate the effect of tape, or tubes, or transformers on these types of sources, I can gently round their transients into compliance without messing with the internal balance of the mix.

Rather than expecting a 2-mix compressor to grab these transients (which will momentarily affect everything in the mix each time it does) I prefer to deal with them individually to maintain the mix balance. If I selectively control these elements, I can then leave the full dynamics of everything else comparatively untouched.

Being able to pick and choose what elements I think needs “control” rather than being forced into wholesale processing across the entire mix allows me to deliver a mix that is both dynamic, densely packed, but still well-behaved and nicely controlled. This helps the mastering engineer do their job by giving them a track that is easy to “make loud”.

Since I am very protective of my mixes when I send them out for mastering, the more “finished” the mix sounds when it leaves my studio, the less (I hope) the mastering engineer must do to deliver a great master.

I could just disregard all of this obsession about metering and reference levels and still get decent results, and I’m sure that many do. But in order to safely navigate the murky waters of music delivery these days, being able to ensure some kind of predictable quality no matter where your clients’ music ends up is an important responsibility.

Delivering great mixes is the best approach to be sure, but not allowing downstream compression or level restrictions to negatively affect the mixes is taking this responsibility one step further. For me, using VU meters, and then correlating them with some kind of meaningful standard has allowed me to do that more consistently. I’m always aware of how close I am to reaching the dreaded digital full scale, and I actively work to keep the margin between average and peak levels where I want it to be.

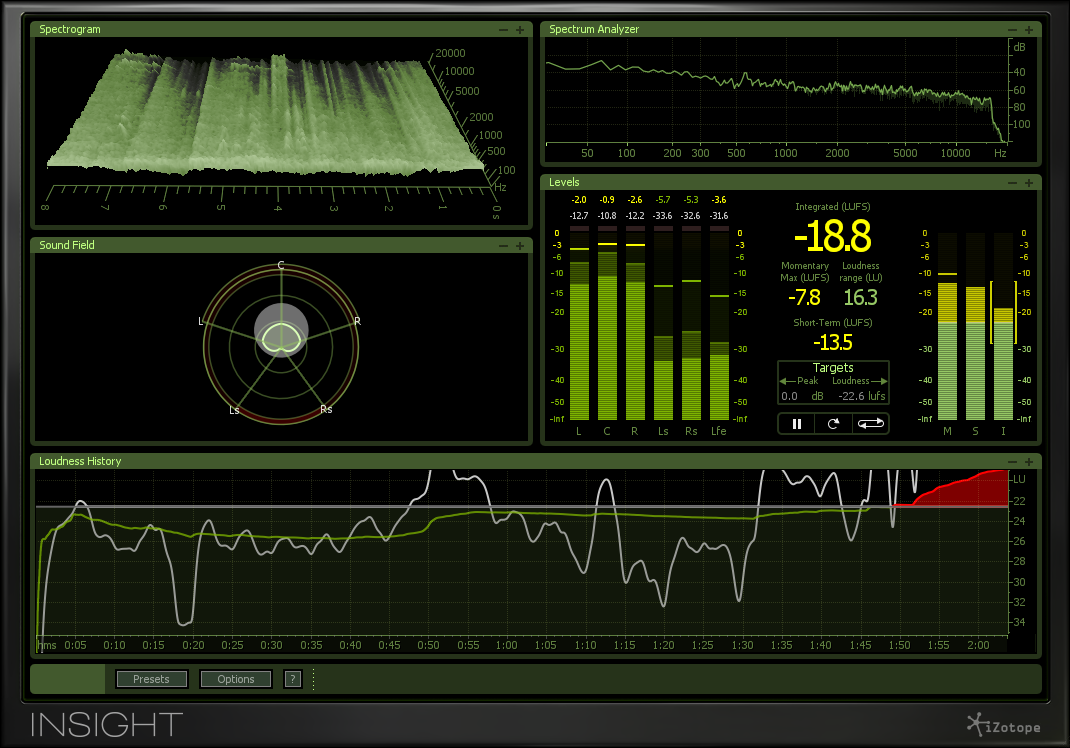

In addition to an increasing number of in-the-box VU and loudness, meters, full-fledged meter suites like iZotope Insight can help keep you truly informed about what’s going on in your mixes.

As reliant as I am on my VU meters, they don’t tell me everything. I will occasionally use iZotope Insight for its loudness metering, frequency metering, and other empirical measurements.

When mastering, it is almost imperative to know what the absolute peak values are and Insight has very accurate, numeric readings for both conventional RMS averages and LUFS (“loudness units relative to full scale”).

Recently, I have become quite comfortable with the metering in Nuendo 8 also, which is versatile, feature-laden, and easy on the eyes. Between these three references, I am fully confident that what I’m sending downstream is well-accounted for and safe for mass consumption.

Today, an increasing number of in-the-box VU meter plugins are available from low-cost developers like PSP and Klanghelm, And for those who want a next-generation approach to level metering, loudness unit meters like the K-Metering system, Waves WLM and the Dynameter are also available, in addition full-featured suites like iZotope Insight.

The Zeroes of Others

Knowing the circuitous route I traveled to arrive at my preferred reference level, I thought it would be valuable to ask other trusted colleagues about their reference levels and why they use them.

Ashley Shepherd, producer at PICTUREMUSIC and owner of the fabulous Audiogrotto in the Cincinnati area has some varied and specific standards under which he operates.

“I use Nuendo which has a quite useful master meter capable of K-system, AES digital and even LUFS metering so normally I do not need any other meters besides what Steinberg provides,” he says. “On occasion, I will use the spectral meter from iZotope for frequency-specific levels.”

Ashley generally mixes and masters adhering to the “K12 reference-based on the Bob Katz K-system” but confessed that when people want it “loud as hell” (and who doesn’t?) he will work reluctantly at a K9 reference level.

Citing Nuendo’s versatile metering he notes: “Film and post production must meet broadcast guidelines. For that, I use the LUFS meter in Nuendo and follow broadcasters’ instructions.”

John Stephan, owner of the remarkable Springs Theatre Arts & Recording in Tampa uses his Dorrough Loudness meters and the meters in his DAW to keep an eye on his levels throughout the recording process.

He “calibrates his monitors with pink noise” to 85dB SPL, referenced to -12dBfs.

This is much like the K-System (which Ashley Shepherd also mentioned) where a fixed monitor volume is used as an absolute reference point.

The wisdom behind the 85dB SPL reference point is that human hearing is at its most accurate at that level. By listening at this level your sense of tonal balance is not skewed by volume-which is a common pitfall faced by less experienced engineers.

Seattle-area engineer Tom Hall [Queensryche, UB40, Eric Tingstad, Tangerine Dream, Triad Studios in Redmond, WA, Live On-Air mix engineer for KEXP in Seattle] of Earworks Audio has a looser, more varied approach:

“I work on a really wide selection of musical styles; some are meant to melt your face off, some to stroke your delicate sensibilities. I mix for what will best suit the music. I use meters to make sure that I’m not leaving any resolution on the table. For me, aside from that, if it sounds good, it is good.”

However, he did qualify that with “If I had a reference, it would probably be around -14 LUFS…that seems to be where I end up a lot of the time.”

While Tom does not concern himself much with a specific target or reference level while mixing, he does pay close attention while tracking:

“When I’m tracking, metering and gain structure are vital…even down to getting the best gain structure for cues. I constantly reference the indicators and meters on the mic pre’s, compressors, A/D’s, DAW, and headphone amp. Once it’s all in the box, I’m most concerned with how it sounds and feels and making certain that I’m using all of the available resolution.”

Tom’s preferred meters?

“When working at my own studio or an outside studio and working ITB, I mostly rely on the internal metering in ProTools, and I prefer the ProTools Classic VU. Back when we were mostly working on analog consoles, I relied on meters a lot, and found LED and plasma meters to be useful but different from traditional VU meters. I’ve also recently been using the Waves WLM … mostly to confirm what my ears are telling me.”

Meters Can Show You the Way

The whole reason for the history lesson about metering and reference levels is to help you understand how it all relates to your workflow.

The gain structure of your mix, the input levels into your plugins, and how you drive your buses and outputs are not small details that can be glossed over; especially if you’re trying to do professional work.

With our modern obsession with all things “vintage” or “retro”, it certainly helps to know how and why engineers drove things the way they did in the past to achieve these types of sounds.

Usually, it was not haphazard or a mistake. As a rule, professionals don’t leave technical details to chance, and usually develop their processes based on methods that actually work—not methods that others say are nostalgically authentic. Establishing reference levels and knowing how to use and read meters is necessary to do this with any regularity.

Ultimately, the point of recorded music is for it to be consumed in some way at a later date, whether it be on vinyl, streamed to a phone, downloaded and played back on a computer, or featured in a TV show or web series.

All of these formats have parameters under which they perform their best (read: where they change your music the least) but they also have limits and restrictions based on the delivery format. Knowing how to deliver music across multiple formats and standards is a core reason that meters were invented in the first place. And that is fodder for a whole ‘nuther article.

In the meantime: Don’t fear your meters. They’re only there to help.

Mike Major is a Mixer/Producer/Recording and Mastering engineer from Dunedin, FL.

He has worked with At The Drive-In, Coheed and Cambria, Sparta, Gone is Gone, As Tall as Lions, and hundreds of other artists over the last 30 years.

Major is the author of the book Recording Drums: The Complete Guide.

Please note: When you buy products through links on this page, we may earn an affiliate commission.

DPrty

January 26, 2018 at 3:24 am (6 years ago)Really good article. Thanks

victor

January 26, 2018 at 2:07 pm (6 years ago)someone please help me with this…. so if i give a mastering engineer my digital master, and it peaks at let’s say -.5, a half a db of headroom so we are sure there are no peaks at or over zero. if the mastering engineer needs a few more db of headroom, , why can’t he just pull the level down himself 3 or 4 db in the digital realm before he starts his mastering chain?… why do i always hear the importance of leaving those db at the top when i mix, when he (or she) could just as well do it. seems like it would be exactly the same as pulling down my master fader before i print the mix.

Maleet

January 26, 2018 at 9:27 pm (6 years ago)This was an excellent article! My question however would be since analog emulation plug ins such as UAD LA2A are calibrated at -18dbfs for an optimal input level, is coming in at -14dbfs going to drive it to drive it to hard when it comes to gain staging? Should I have my track levels at -14dbfs or does the -14dbfs only apply to the master bus level? Thank you for insight.

Mike Major

January 27, 2018 at 5:19 pm (6 years ago)Thanks Maleet! Glad you enjoyed it.

I only drive the 2-Mix at -14dBfs but I make up that little bit of gain on the stereo buss after I have the mix together. I run my mixer internally much lower than that. It’s kind of a complicated gain structure if I was to break it down, but in a nutshell, I want my faders to hover around unity because of the finer resolution when writing automation. I trim the inputs (with clip gain or the like) so everything can live at unity to start. Then I make sure the groups don’t drive the stereo buss too hard either. It’s easy to make it louder later.

Mike Major

January 27, 2018 at 5:34 pm (6 years ago)There are different schools of thought about this so I understand your confusion about it.

I think some mastering engineers ask for more headroom to make sure that people don’t drive the output too hard without regard for the peak to average ratio. Maybe it’s a “better safe than sorry” scenario. Ultimately, I think mastering engineers just want to make sure they have

somewhere to go, and maximizing and limiting a mix to death does tend to paint the mastering engineer into a corner. That’s no fun.

If you’re cautious (or at least aware or vigilant) about your peak levels throughout the process then you may deliver something that’s in better shape, rather than just burying the stereo buss in the red and then turning it down at the end. That’s an indication of other problems, I think.

My habits were established on analog consoles where turning it down didn’t always fix the problem (as I stated in the article). By working within those constraints I had to tend to the level housekeeping at all times. Digital mixing has helped to eliminate that problem but it doesn’t mean that the gain structure of a digital mix is healthy even though there’s no peaks.

When I master stuff that’s sent to me too hot, I just turn it down and I don’t think it’s a big deal. I know that technically, you are losing bits when you do that, but in the grand scheme it’s insignificant. If the mastering guy is mastering in analog, then they can trim it before it hits their first analog device to get the gain structure right through their signal path.

Mike Major

January 27, 2018 at 5:34 pm (6 years ago)Thanks! Glad to hear it. I half way expected that no one would care much about this subject but thankfully, I was wrong!

DPrty

January 28, 2018 at 1:15 am (6 years ago)Well it’s an important subject if you’re hoping to get good result’s and there is not a ton of well written informative article’s around on this. I will be pointing some of my friends at this article. So yes we care and thanks.

Dale Seppie

January 30, 2018 at 2:50 am (6 years ago)Great article, thanks for taking the time to write this. I have one question on one of the points highlighted: how does one calibrate one’s monitors or even headphones to the 85db SPL mark which you pointed out delivers the most accurate reference for tonal balance?

Mike Major

January 31, 2018 at 3:40 pm (6 years ago)Glad you liked it Dale. That’s nice to hear.

Here’s an article by Presonus about the calibration procedure.

https://www.presonus.com/learn/technical-articles/how-do-i-calibrate-my-studio-monitors

Bob Katz’ book also has a full chapter on using his “K-system” and calibrating your monitors to one of the reference points. It’s pretty detailed and to do it correctly takes some time. In the most basic sense (which kind of defeats the point of an absolute reference), you have to send pink noise at your average mix level out of your DAW (for me, around -14dBfs referenced to 0VU) and then turn the monitors up until the SPL meter reads 85dB C weighted, slow response. If you do this, wear ear protection!

Mike Major

January 31, 2018 at 3:41 pm (6 years ago)And the video as well with some good points:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=idGvZnSnPhs&index=155&list=FLlSEjHIIYBRYH1efBup9m1g