Mixing By Feel: Chris Tabron Taps Into the Emotion Behind His Workflow for Son Lux’s “Labor”

There have been plenty of powerful articles on SonicScoop about mix techniques. Compression ratios, EQ settings, and automation ideas have been shared — and will continue to be.

But today we take a pause from the technical side of mixing, and switch to another dimension that’s equally essential to outstanding results: It is in this intellectual hemisphere where Chris Tabron resides.

Splitting time between NYC and LA — with his official mix HQ in Brooklyn’s Bushwick nabe — Tabron has built up a noticeable portfolio in his career, for such clients as Beyoncé, Nicki Minaj, Mary J. Blige, Common, The Strokes, and Erykah Badu. His moniker of Madison Avenue Girls gives Tabron additional license to produce pop and hip hop, as well as remix.

Perhaps not surprisingly, his discography also includes the artist Son Lux, whose beautiful broodings most recently resulted in the recently released album Brighter Wounds. Inventive in its artistry, it’s a record as much crafted as it was written and performed by its band members Ryan Lott, Rafiq Bhatia, and Ian Chang.

Tabron’s friendship with Chang, plus some old skool hustling, won him the opportunity to mix the majority of Brighter Wounds. First up was “Labor,” which Tabron calls “the Rosetta Stone” for the rest of the album. Tabron’s mix is a vessel for the song’s fragile majesty, allowing all its rawness, refinement, deep thought and longing to reach the listener’s ear seemingly untouched. Vocals solo and in choral layers, strings, drums, and space weave together with strength and subtlety until — before you know it — this 4:10 mini-movie is over.

Tabron worked out of his Brooklyn studio Rumours to mix “Labor.” A hybrid analog digital setup, it features such niceties as PMC IB2S-A monitors, a Crane Song Avocet, and Pro Tools HD 2018 in the driver’s seat. Outboard includes Neve 33114 preamps, Neve 33609 C compressor, Empirical Labs UBK Fatso, and AMS RMX 16 Reverb. Conversion comes courtesy of Dangerous and Avid units.

But you won’t hear Tabron discuss gear when he reveals his mixing techniques for the masterful “Labor.” That’s because his own labor is focused on pre-production psychology, maintaining a creative mindset, and knowing when to say “when” – all invaluable parts of the mix process that he shares here. As for those compression ratios, EQ settings, and automation curves? Tabron just goes into the zone.

Why is it important for you to not just get to know the artist’s music, but the artist’s motivations and intentions, before you mix the record? How does that change what you can do for them?

Well, sometimes the artist’s existing body of work might not be enough context for where the current work is headed. I’m fortunate that many of the artists I work with don’t want to make the same record over and over, so even if I’m really familiar with their previous work (or worked on it myself) I usually am pretty firm about not listening to old work.

Also, I like to engage the artist in talking about their music in terms of emotions and how they want to feel when they listen to it. The more they are in that frame of mind when we talk about their work, the better it will be for the entire process and the work we’re doing together.

The scientist side of me loves to tinker with gear, pop the lid open, see how it’s made and maybe even modify it. But I do that on my own time. When it comes time to mix a record I’m not thinking about my gear any more than a painter is thinking about his or her paint brush. It’s my job to find an emotion’s technical correlate, so I can’t do that if I’m thinking all the time that I’m mixing. I need to be in the same head space where I’m just playing similar to how an artist isn’t thinking when they’re playing.

I wouldn’t say my approach is anti-technology, but more about using technology toward a humanistic outcome. It’s easy to think that technology is oppositional to humanity, but I think one of the foundational technologies we have is language. I want the artist communicating to me in as colorful and detailed language as possible about their art. Sometimes that’s as simple as asking why they chose a certain word in the bridge, or watching how they dance to the rough mix. Or sometimes it’s knowing when a thing can’t be explained and they just tell me how they want to feel when they listen to the song.

In terms of how that changes what I can do for them, I think it helps me better understand the nuanced aspects of their song, put that into a sonic presentation that’s going to be appropriate for what it needs to be, but also help them know when it’s done and we’ve reached that goal we set out to achieve.

Head Room

What are some of the techniques you use to stay in the proper headspace once you start mixing?

One of the biggest—and sometimes overlooked—aspects is having a good assistant prep the mix for me. I’m lucky to have a couple of guys who are really good at tracking down missing files, making sure we have the latest reference mix, interacting with the client on getting dry versions of tracks printed, etc. so I don’t have to get too mired down in that left brain side of things right when I sit down to mix.

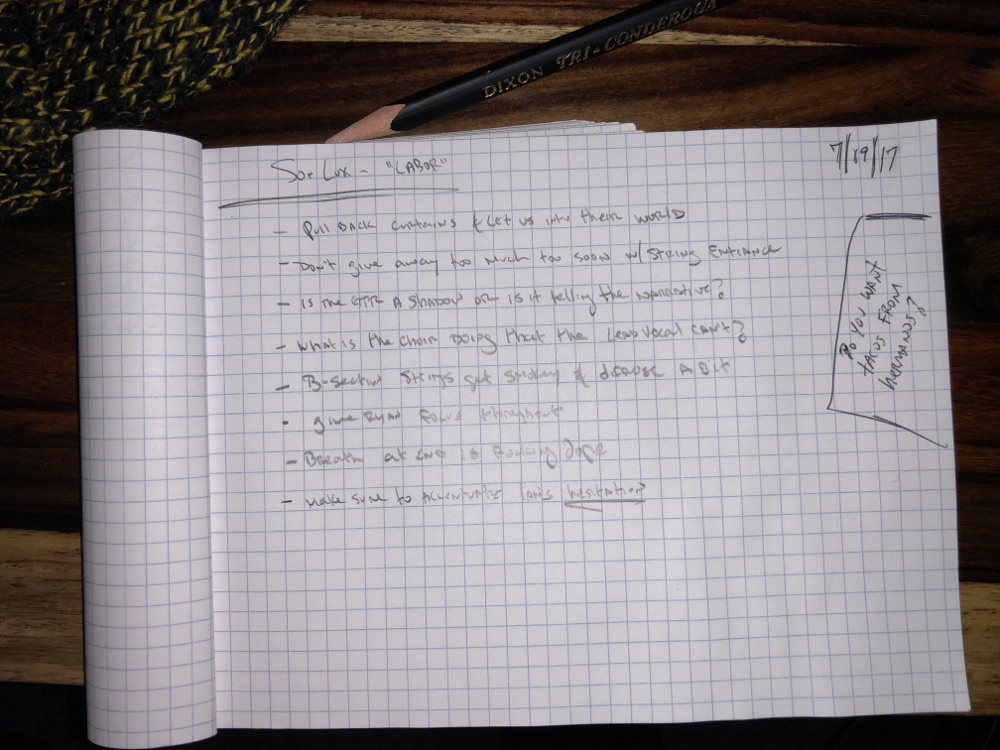

The first thing I always do, is to play the reference mix down in the Pro Tools session. Instead of sitting at the computer, I sit on the couch in the back of the room and take notes with a pencil and paper. I like to write notes out long hand rather than type because typing is so much quicker, it’s hard to not try to keep up with the song which is NOT what I want to do. If my idea is good enough, I’ll remember it when I finish writing the previous one; it’s good to be deliberate about your ideas rather than just fast.

Once I have those ideas down (I found the photo of what I wrote down for “Labor” attached) I start mixing pretty quickly right after. During the next 45 mins to an hour, I just play the song top down and try not to do any stopping or much solo-ing. I try to get a feel for the energy flow of the song, and implement rough ideas I have and see how the arrangement responds. It’s usually in this phase where I know what I want to do is gonna work, or if I have to figure out another approach.

Somewhere around the hour mark, I print a pass of where I’m at and I take an ear break. This mix pass never gets sent to the client, and it’s usually pretty rough around the edges, but there’s always something worthwhile in there during the early stages before I get too familiar with the song. The purpose of this mix (that I will reference later as I move along) is to capture the phase where I was reacting like a listener might, just playing off of the arrangement and production. It’s also a good chance for me to listen to any happy accidents I may have made by just throwing up faders and not refining my balances.

Other than that, I have quite a few speakers that I listen on, and once I’m in the thick of mixing I tend to get up and move around the studio a lot, or listen on the couch in the corner way off-axis to the speakers, or stream it to my laptop speakers. Sometimes I’ll have the TV on low volume and kinda ignore the mix and see if it’s still keeping my attention. I’ll flip back and forth between the reference mix and mine occasionally, but unless I was told specifically to not change a certain element at all, I don’t like to get anchored by the other mix on this first pass. In general, I mix rather quietly, especially when doing vocal rides, so I don’t get burned out if I have to mix 2-3 songs a day.

One thing most people don’t realize about modern mixing workflows where you usually don’t have a big console in front of you is that it’s much easier to just sit in the sweet spot all day, which can be a bad thing. If you had a 64 channel desk and you had to get up and walk down to channel 9 or across the room to the Pultecs, you get used to hearing the mix in all parts of the room out of habit. So I try to keep that cadence of moving around in mind.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, how do you know when you’ve completed the task of mixing a particular song? In other words, how do you know when it’s “done”?

Mixing is one of those things that the better you do it, the less evidence there is that you’ve done anything. The goal of mixing is not to hear the mix but to hear the song, so I guess I know it’s done when I just hear the song and not the mix.

Now, I remember hearing the great Bruce Swedien say in an interview that an engineer often gets the feeling of being “finished” but much less often gets the feeling of being “satisfied,” and that’s something I 100% understand.

Sometimes, you just have to be “done” even if you’re not “finished” because of deadlines out of your control. But one of the things I ask myself before I send a first mix pass to a client, or before I send final passes to mastering, is “does it feel right?”

I may make 50 small adjustments or decisions on a record that I’ll be the only person in the world who will notice them (or cares!), but the summation of those decisions will be felt by the artist, and—if we’ve done our job right—the audience. No one cares if I used a 45 year-old compressor or a plugin; they’ll just know if it feels right or not.

Seeking Completion

Is there a way to explain what a song does when it achieves maximum emotional impact — what does a song do to you personally when it hits you “just right?”

It’s tough to put into words, but I think that’s kinda the point. I can’t think of many amazing mixes that weren’t amazing arrangements first, and a lot of mixing is bringing out that emotional impact. I know even as a mixer, when I listen to “Check the Rhime” my ear doesn’t gravitate to the mix. The mix is so perfect, it’s just an amazing song.

I’ve spent many, many hours studying mixes of people like Bob Power, Bob Clearmountain, Russ Elevado, Tony Maserati, and others but one thing a lot of their work usually has in common is that it’s hard to not get distracted by how dope the song feels when you’re trying to figure out what kind of vocal reverb they used. I remember having to rewind many times and saying, “ok this time without singing along!”

So, I’ve often said the best compliment I’ve ever been given on a mix of mine is “Wow, what a great song!” Similarly, when a song hits me just right, I’m probably not doing any thinking at all.

What was the feedback that you got from Son Lux on you work? How did “Brighter Wounds” help you to grow as a mixer?

I have to credit the band for being really open and receptive to my creative ideas when mixing. It’s a delicate situation when there’s a tight-knit unit like Son Lux, who previously handled all of their mixing on their own, to have someone else come into the fold.

From the start, it wasn’t a relationship where Ryan said, “Hey I want this 10% better than the reference mix,” and he really gave me that trust early on to explore. Almost immediately, it felt great to know we were all on the same team, and that we all wanted what was best for the record — that’s quite a privilege to get that commitment in a creative relationship early on.

Ryan’s also a good mixer in his own right, so it was great to be able to hear what he was doing on the few songs on the album I wasn’t mixing, and we would pass notes back and forth to make sure everything we were doing would gel together. It was also great to know that from the first pass of the first few songs I was going in a direction that they really liked.

Brighter Wounds was the first full-length I mixed since getting new main monitors (PMC IB2S-A), so I made sure to reference on lots of sources as I got used to the detail of the PMC’s. In general, working with Son Lux was one of those experiences where everyone on the team was on their A-game and it makes you push harder to get better.

Finally, what advice do you have for emerging mixers who reading this that want to grow and nurture their own skills? How can they be a Better Mixer?

A lot of my guys say they want to be a mixer and I tell them all the same thing: Record as many artists and bands as you can first.

It’s not like you won’t be doing any mixing during that time, but most younger engineers in their early 20’s don’t have the discography or experience to have people reach out to them for just mixing. Plus, you need to record hundreds and hundreds of artists in different situations so you can know what a Tele sounds like vs. a Strat, vs a thicker pick vs. a thinner one, vs. a Fender or a Vox amp.

But also you need to be in the room with lots of people, from the producer to the drummer, to the drummer’s roommate’s girlfriend to whoever, and know how to navigate those personalities as it’s a useful skill in your career. Also, being a recording engineer gives you a front row seat into those moments in the room when the vibe is perfect and you know that was the magical take of a song — and that’s the very energy you’re looking to make sure is showcased in a mix.

In terms of developing mix skills, well MIX! Mix your friends’ stuff for free, download stems of popular songs and try to match the mastered version. You have to make a commitment to be a student of the craft and study the greats across all genres. If you don’t have the bug where you want to spend your down time reading up on how they made “September Gurls” or scan interviews with Susan Rogers, then mixing probably isn’t going to be the right fit for you.

Understand the reasons certain technical decisions were made on classic records, and how that impacted the outcome of the song. Also, don’t be afraid of learning from the work of the younger generation of mixers who are doing really innovative work and pushing boundaries in their craft as well. You have to have an insatiable desire to learn and improve yourself every day because it’s a lifelong journey towards mastery.

I never went to engineering school, but I was lucky enough to have a background as a DJ and know a decent amount about a lot of different types of music from all around the world. So if you don’t have a similar background, I’d say study music that’s not the type of stuff you listen to for fun. Combine that with listening to lots and lots of work that you know sounds amazing, and no matter what type of speakers you have, you’ll start to learn frequencies and how to get them to get along in a mix.

One technical piece of advice I can say applies to most young mixers is mix quieter. Yes, you! Turn that shit down, you’re not going to impress anyone by mixing loud and you’re going to shorten your career. Plus, your sense of balances really goes to hell at loud volumes.

Also, limit your processing. Make sure you’ve got the right balances and panning before you start getting plugins involved. Mixing is as much of what you don’t do as it is what you decide to do. Get people’s opinions of your work, and get used to not taking feedback personally.

Don’t limit your feedback from other engineers…play a mix for a non-technical music fan and ask them what they think of the song. If we only made music for other engineers, there’d be no platinum records.

— David Weiss

Please note: When you buy products through links on this page, we may earn an affiliate commission.