Mixing with Impact: 12 Ways to Command and Direct a Listener’s Attention

This is a guest post by Wessel Oltheten, a producer, engineer and author of the new book Mixing with Impact.

One of the producer’s most important jobs is to be a steward of the listener’s attention, helping to direct it to the most important elements.

I recently took part in a blind comparison between the work done by various human mastering engineers and a popular ”artificial intelligence based” algorithm.

While the algorithm did a respectable job, it also made me realize that the things we sometimes see as goals in music production—a good frequency balance, impressive dynamics, a wide stereo image, transparency—aren’t important in and of themselves. They are just the ways we use to achieve the highest goal of all: Guiding a listener’s attention through the music.

Try to think of the time before you got “contaminated” with all sorts of inside knowledge on music production. Remember how you experienced new music without dissecting its ingredients, and without thinking of how you could create something similar yourself.

In that non-analytical and open state of mind, your attention is free to go along with the music. It can be captured by a musical element that drags you into the story, while other elements support or oppose that movement.

You form expectations of a kind of sonic story, which can then be granted or broken. After a while, you hear elements you didn’t notice before, and they can draw you into even deeper layers of the arrangement.

When the presentation is executed well, the music can demand your complete attention and evoke strong feelings or associations in the process. It puts your mind at work on multiple levels: Cognitive, associative, and emotional.

That presentation is music production, which is our main focus here. To me, production is about telling a story with sound, by giving a listener different focus points over time. When you think about it in that sense, EQ is not a means to prevent masking but a way of steering attention towards (or away from) specific musical elements.

This change in mindset can be helpful, because quite often, masking isn’t a problem to be corrected but a feat to be accomplished: If a particular element is meant to have a supporting role, perhaps it’s better that it’s partly masked and that you don’t consciously become aware of it before the fifth time you hear it.

When it comes to these kinds of decisions, the mastering algorithm didn’t perform well; it obviously can’t understand musical context or role division. An algorithm only sees problems it can fix—like so many novice engineers.

The way you experience music—which is what music production should be about—has a lot to do with you shifting your attention at various times. The musical structure partly decides for you where your attention should go: If there’s a clear change in the arrangement, you have to go along with it. But within this musical structure, there is also freedom. You can direct your attention to various aspects of the whole. That’s why every time you hear a piece of music, the experience is different.

Because music is a multilayered art form, in which many interesting things can happen simultaneously, you’re always allowed to focus on an element of your liking, and thereby change the pathway you follow as the music progresses. You can find many such pathways when listening to a piece of music multiple times.

When its too easy to discover all the different pathways through a recording, music reaches its full emotional potential almost on the first listen. But I’ve also noticed that I tend to get bored with it pretty quickly after that. For me, music that takes me five or so times to get familiar with before I feel its maximum emotional impact is at a kind of sweet spot. If it takes me longer to get there, I tend not to push through and just play something else. If it takes me fewer listens, I usually move on to new music fairly quickly. Perhaps you can relate.

The author, Wessel Oltheten, at work in the studio. His new book Mixing with Impact is out now.

Obviously, the balance between cognitive effort and not getting bored is a highly personal preference, which is subject to previous experience, taste, mood, time of day, and so on.

The important thing to take away from this is that listening to music requires effort, and the amount of effort should be adapted to a particular setting and audience.

As the designer of a musical experience, you have to think like a person you’re designing for—and that person may not have the same knowledge about the musical contents as you do. What would they need to be intrigued—and not put off—by the first spin of a record? Or, what’s needed to deliver emotional impact to them, even on the first listen—like film music is required to do?

These questions tend to be hard to answer when you’re already intimately familiar with the music yourself. This is why your first contact with a piece of music is so important. The moment a film composer puts his first mockup under the picture will never come around again. The time you first play the demo of an artist you’ll be producing will never return. It’s these experiences from which you can learn the most about what a production needs. So be mindful of what attracts your attention, what speaks to the imagination, but also of what distracts from your experience.

These insights can be used later on to design a production that works even better. It can give you the perspective you need to present the listener with more of a clear structure and division between elements so you can lower the threshold for being engaged on the first listen. Or, you can do the opposite and purposely break some of these expectations, to prevent them from thinking that they’ve heard something like this hundreds of times before.

In music, there’s usually not a concrete storyline like in a movie, but there are al kinds of patterns that form a coherent structure. If you can make this structure comprehendible you’re allowing a listener to find her own way through the music—and enjoy all its substructures and patterns— without losing track. It very much resembles the job description of an orchestra conductor: To determine where, and at what time, emphasis should be placed within a complex whole.

Attention Mechanisms

Of course, you don’t directly control a listener’s attention. There’s no way to prevent them from just focusing on the lyrics to a song, or from not noticing what is being sung at all.

Much of where listeners put their attention by default is due to differences in personality, cultural background and listening circumstances. But what you can control is whether or not your production makes sense to the average listener. That means you need to position elements of greater importance in a way that makes them attract more attention than less important elements for a casual listener—someone who isn’t actively focusing their attention.

To be able to do so more effectively, let’s first look at some of the mechanisms that influence the amount of attention a sound attracts:

1. Absolute Nearness

When a sound source is close to you, it automatically gets high perceptual priority. That makes sense, since physical objects that are nearest to you can usually impact your life the most—be it positively or negatively.

You perceive the distance to a sound source in a number of ways: The relative loudness of a source, the amount of high frequency detail, the amount of reflections versus direct sound, and the amount of shift in perceived location and diffraction effects when you move your head are the main factors your brain relies on.

When a sound is located extremely close to a listener, it can yield a discomforting sensation. I call this “entering a listener’s personal space”. I usually avoid this bone dry, mono, and overly loud zone in music production (apart from special effects), as it tends to ”push the listener away” from the music.

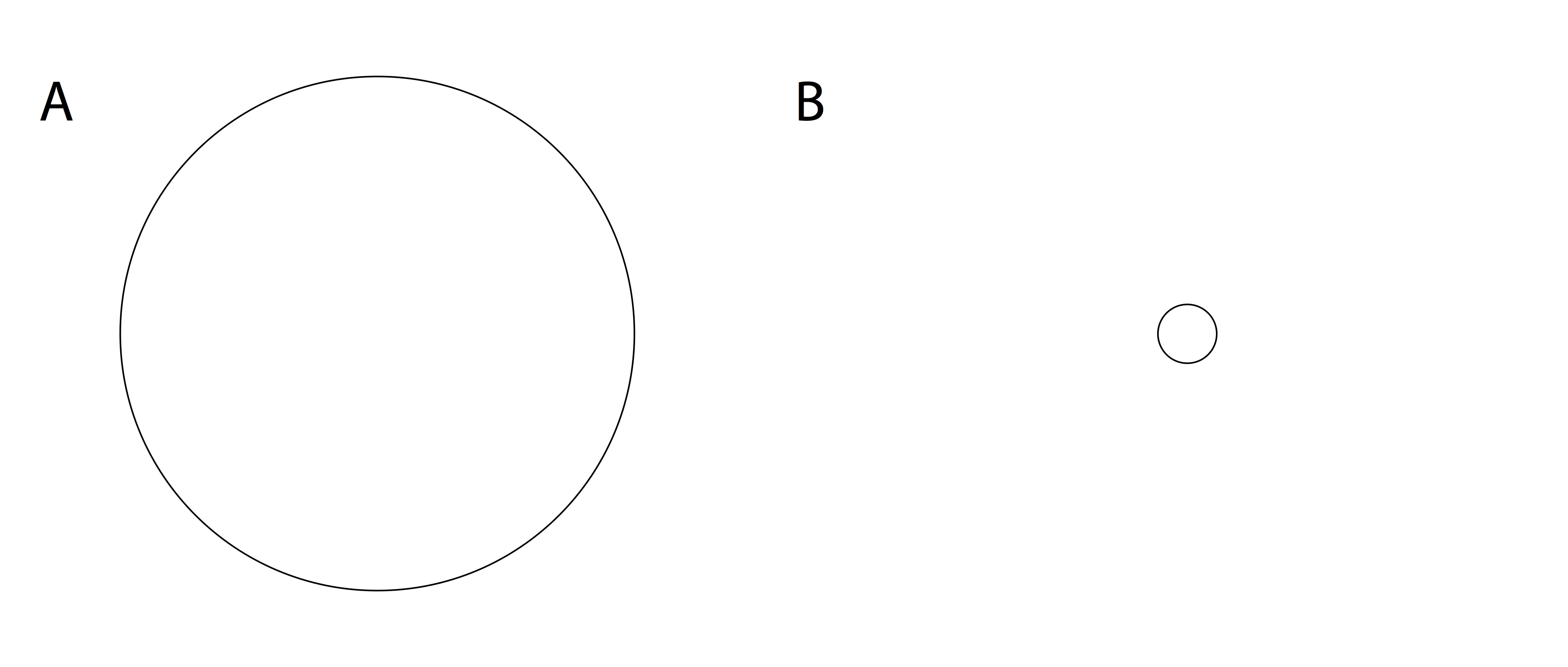

Figure 1: The average person’s attention is automatically drawn to the circle that’s closest. (In this example closeness is only portrayed by size, though in reality it depends on multiple factors).

2. Relative Positioning and Grouping

In the perception of simultaneous sound sources, the way they group together is very important.

When I ride a bicycle, I can only hear the sound of its tires, its dynamo, and the rattling of its fender as separate entities when I put in the effort of consciously focusing my attention on them.

When I listen casually, they are all part of the same perceptual label ‘bicycle’. This is because they all originate from roughly the same location and are all moving in conjunction with me as a listener. This allows my brain to perceptually combine them into one object, thereby saving me some attention to spend on other sounds.This is helpful, because attention is a limited quantity. The amount of sources you can deal with simultaneously and actively is always restricted.

In music production, you can make instruments group together more easily if you place them in the same sonic “location” and have them play similar parts, thereby saving the listener some attention to spend on other instruments.

Alternately, if you want something to attract more attention, have it make an opposing movement in pitch or rhythm, or place it in a different position in the sonic landscape to prevent it from grouping together with other parts.

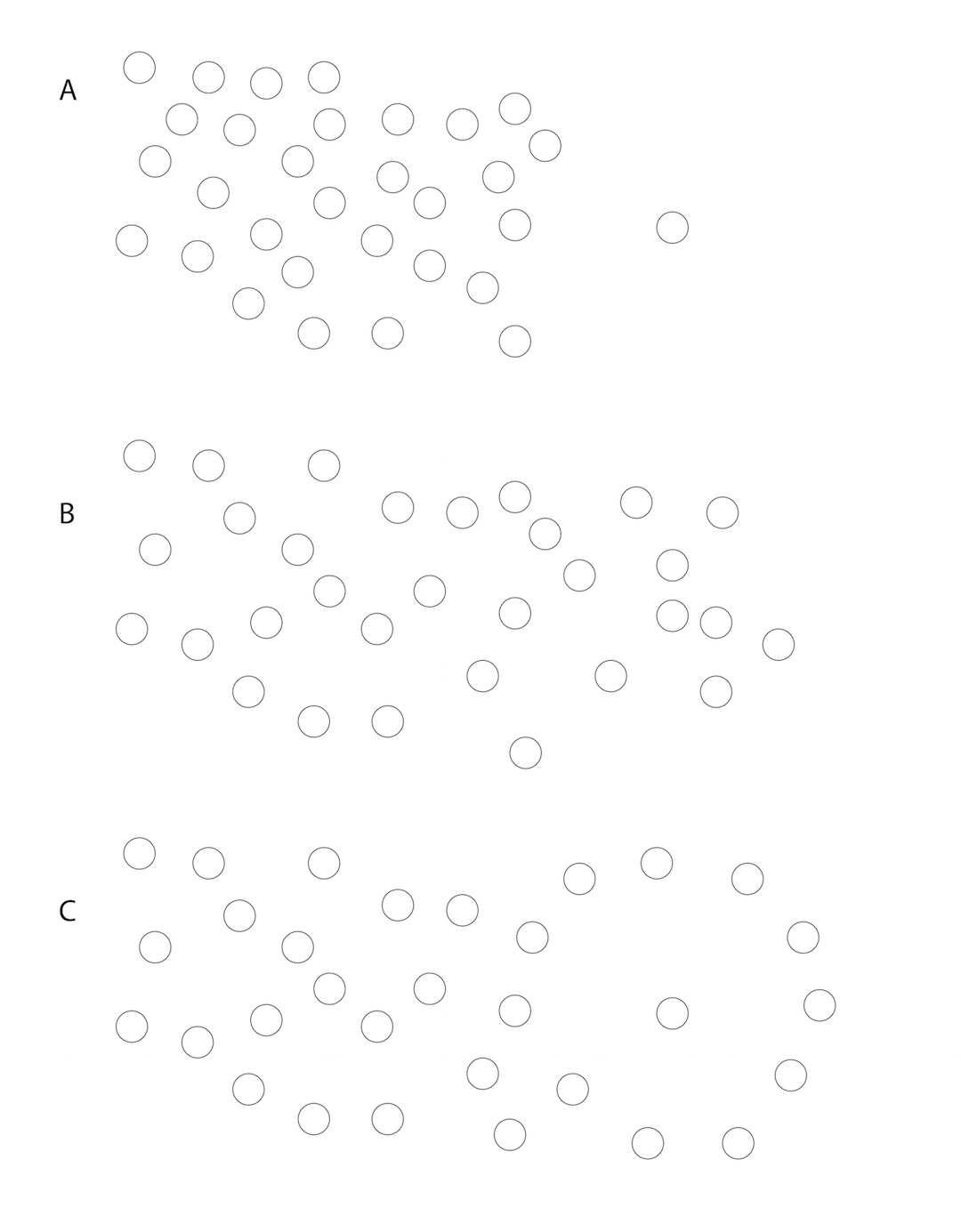

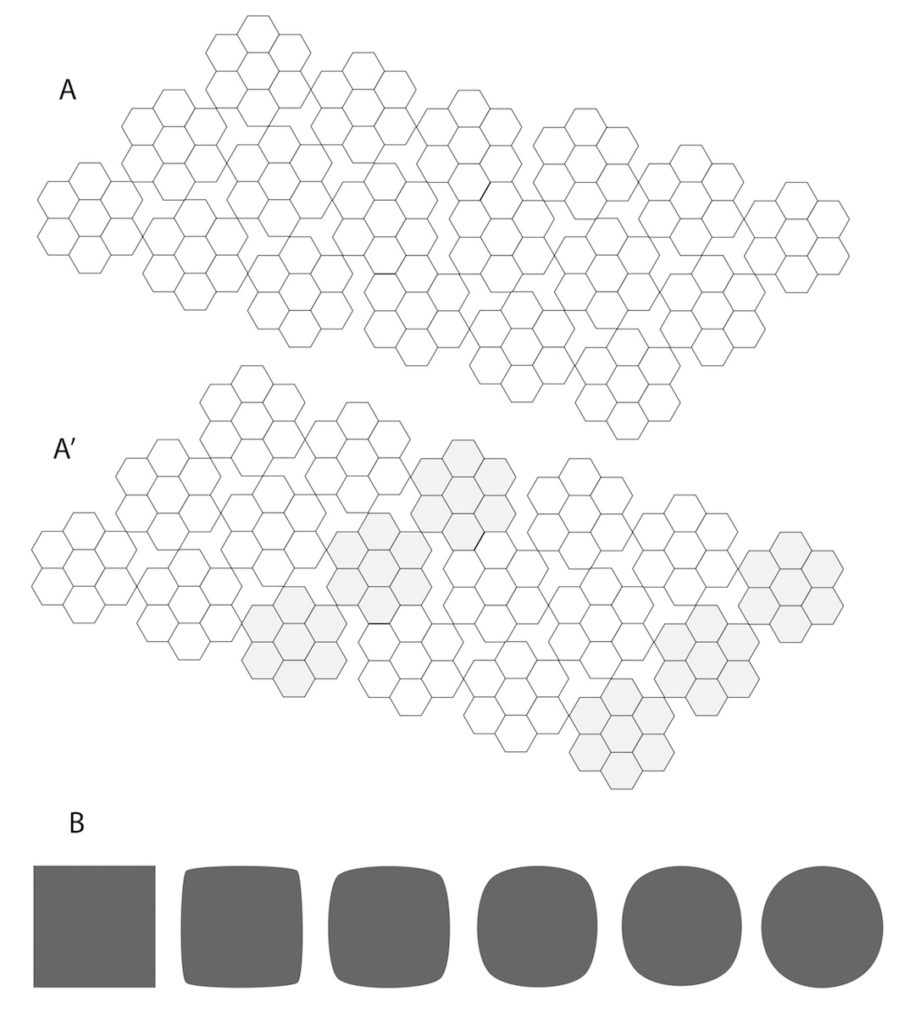

Figure 2: Where a source is located and to what extend it appears to be part of a larger structure, determines how much attention it attracts. The most extreme case is (A): the isolated circle attracts attention straight away.

In (B), the same circle barely receives individual attention, and you only see the bigger structure. In example (C) a pattern can be discovered which places the circle at the center of a different part of the structure, making it seem more important.

3. Relative Loudness

A loud bang attracts attention, but only when the sounds surrounding the bang are less loud than the bang itself. This means that loudness can be a great way to focus attention, but only when there is a difference in loudness (dynamics).

You can hear differences in loudness in time (first it is silent and then a sound appears) or in relation to the surrounding sounds (all instruments are fairly low in level apart from the drums).

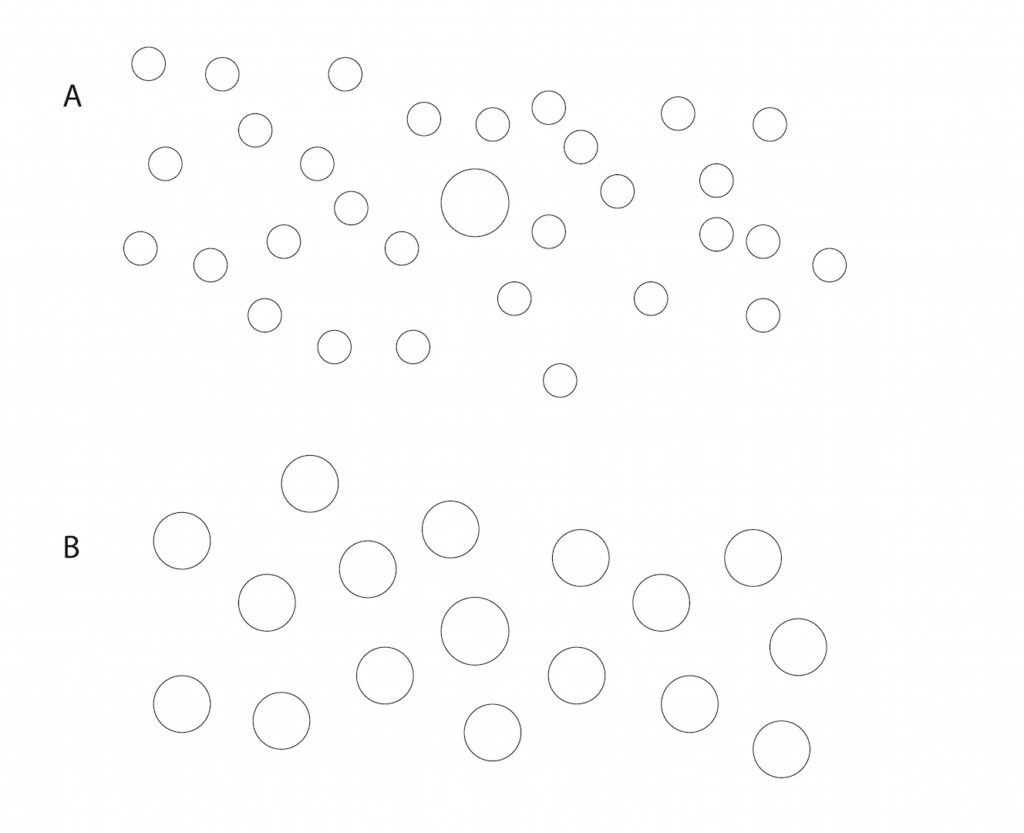

Figure 3: The parts of a structure that are relatively loud attract the most attention. The bigger circle in (A) is a bigger center of attention than the same circle in figure (B).

4. Absolute Sound Color or Pitch

The human ear is not equally sensitive to all frequencies. At an equal level, the sound with the the strongest high frequency emphasis—whether because its fundamental is higher, or because it has more upper harmonics—will tend to attract the most attention.

This is something to take into account during mixing. While high sounds don’t tend to mask other sounds that much in the sense that the other sounds can’t be heard clearly anymore, they do attract attention with relatively ease, rendering other sounds less significant by comparison.

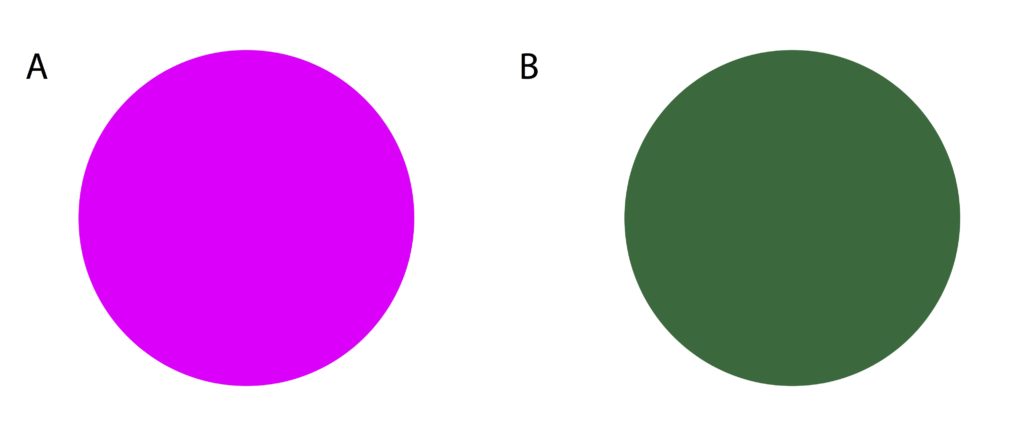

Figure 4: Some colors attract more attention than others. Just like bright pink is more striking than green,instruments with a lot of spectral density between 2 kHz and 4 kHz stick out more than the average bass instrument.

5. Relative Sound Color or Pitch

Putting multiple parts together is what creates musical meaning. Any one of the parts in an arrangement can have a totally different effect on you when you hear it in isolation than when you hear it in context.

For instance, in a C major chord, a B sounds dissonant and thereby attracts more attention, while the same B is more consonant in an E major chord and ”sticks out” much less. In one melody, F4 is the highest note, making it the center of attention, while in the next melody that same note can be an inconspicuous passage tone.

A distorted guitar solo with an extremely dense spectrum of high order harmonics that’s accompanied by low string parts attracts much more attention then the same solo surrounded by two equally distorted rhythm guitars.

Your perception of pitch and sound color is ultimately relative: The surrounding sounds (and their history) determine how much attention a particular sound attracts.

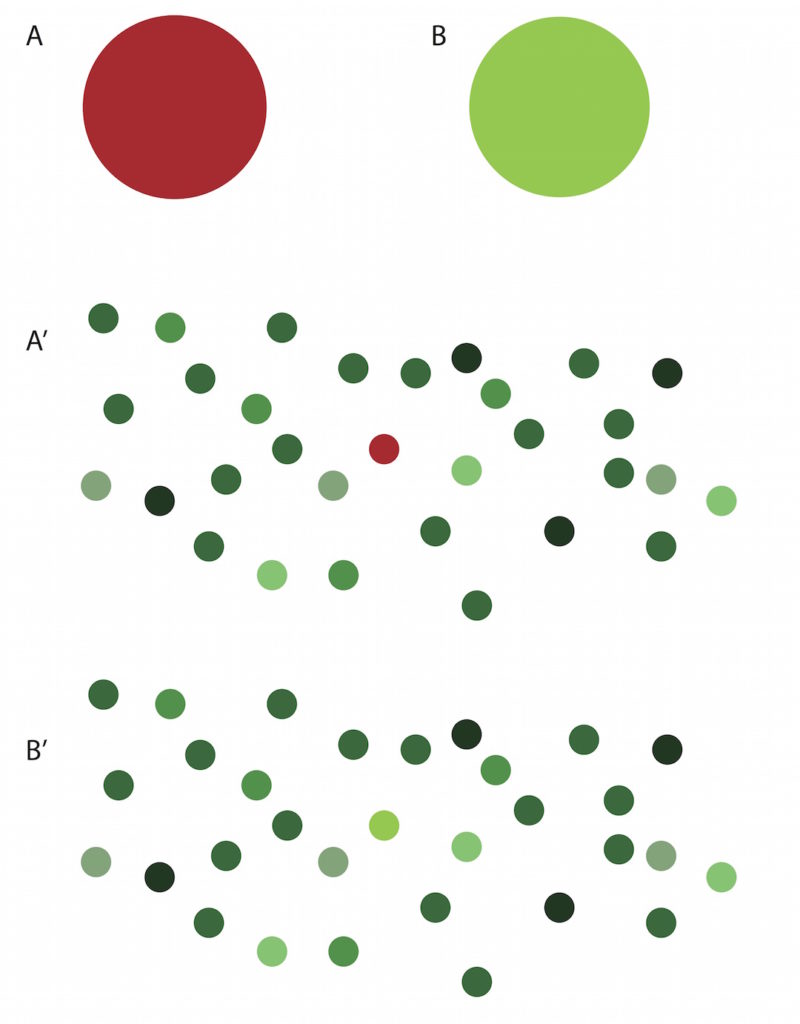

Figure 5: Individually, the large dots at the top of the image are somewhat equal in the amount of attention they attract. But when placed in a context their meaning differs a great deal.

In figure (A’), red is now on hard contrast with the surrounding green, making the circle immediately stick out while the bright green circle barely attracts any individual attention anymore in figure (B’).

6. Contour and Duration

A sound that lasts a long time will automatically attract less and less attention as it goes along. Attention is closely related to change, which implies new information. In absence of change, after a couple of seconds, your attention will slowly start to drift in search of other sources of information.

On a shorter timescale, another related mechanism is at play: A sound can have a sharp contour or a smoother and more fluent one. This can be thought of as the sound’s “envelope”.

Rapid changes in sound, like the ones percussion instruments produce, attract more attention than slowly developing sounds, like softly played legato strings.

There’s an attention hierarchy for the duration of these short sounds as well, but it’s the opposite of the one for long, sustaining sounds. Rapid changing sounds that last only for a very short time (like the fleeting clicks an unsynchronized DA-convertor produces) attract much less attention then percussion sounds with more weight and sustain, that last a bit longer. Only when a sound lasts for seconds without changing, does the amount of attention decrease slowly.

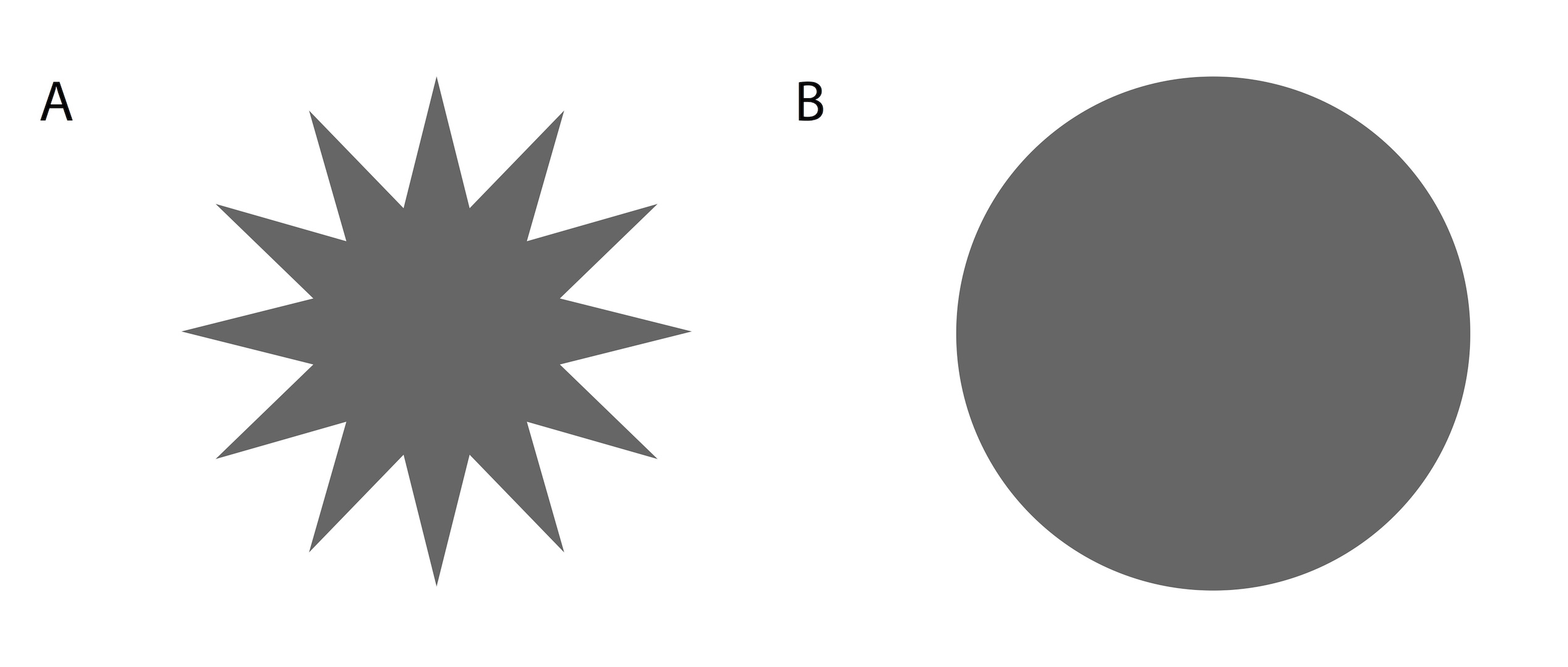

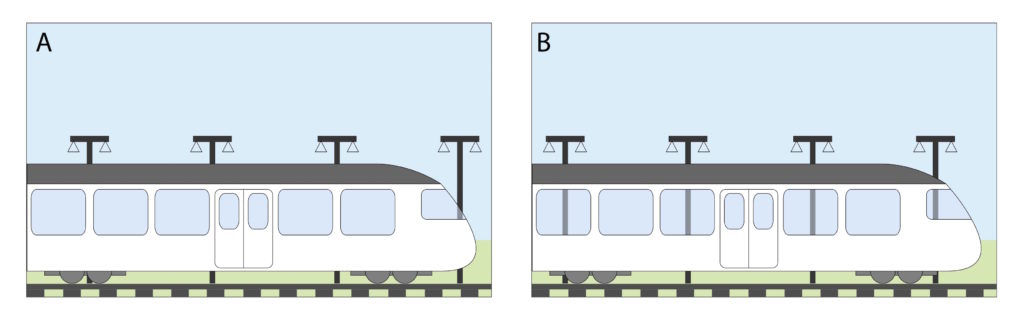

Figure 6: Sounds with sharp contours (A) attract more attention than sounds with smooth or fluently shaped contours (B).

7. Texture

A sound’s DNA (which is comprised of the frequencies of which the sound is composed, their relative balance, and especially, the way they develop over time), determines how much information you can retrieve about the sound source, and therefore how interesting the sound is.

Sounds that have a recognizable pattern, like a harmonic series, or a sound that has been filtered by an acoustic sound box, tend to be more interesting to listen to than sounds that have a more random and noise-like) frequency spectrum.

There’s a good reason for that: The brain tries to suppress noise in favor of information retrieval. Noise can attract attention, but mainly when you give it a sharp contour. It’s the sudden beginnings and endings of the noise that attract the attention, as they imply an acoustic event. When you leave the noise on, it disappears into the background faster than a sustained tonal sound (like an organ) of the same level and duration.

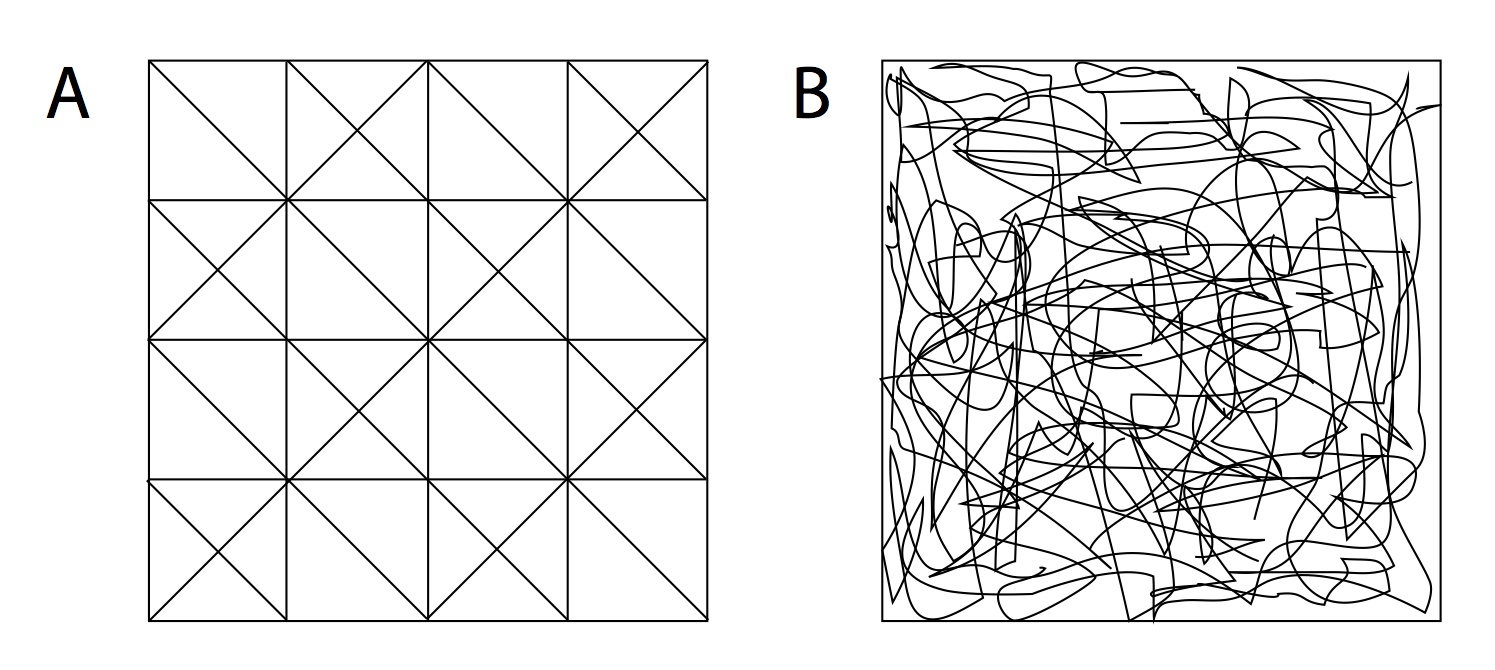

Figure 7: A sustained sound in which you can recognize regular patterns (A) attracts more attention than sustained irregular (noise-like) sounds, in which it is hard to discover information (B).

8. Shape and Location

You can more easily recognize an individual sound source when it is placed at a discrete location in the soundstage. As soon as you spread out a sound—for instance by treating it with a stereo chorus effect, by recording double parts and cross panning them, or by using multiple microphones on the same source and cross panning them—the location of the source in the soundscape becomes more ambiguous.

Take this too far and the source appears to be coming from all around the listener, which for the brain is a sign that the source is part of the surroundings, like wind or reflections. This means the brain is less likely to allocate individual attention to the source, as opposed to a sound that is recognizable as a point source.

Figure 8: Sources that are ambiguous in terms of placement (A) attract less attention than sources with a clearly defined shape and location (B), because the brain is more likely to hear them as part of the surroundings.

9. Synchrony

The time at which a sound is heard in relation to others also determines how much it can stand out and command attention.

When a sound coincides with others and no major conflicts in sound color occur, it will attract less individual attention. It is likely to be perceived as part of a bigger structure—a sound group, like in the bicycle example.

However, when a sound begins or ends at a different moment than the sounds surrounding it, it is more likely to stand out. It can of course still be part of a bigger structure, but it becomes easier to direct attention to the individual part.

On the other hand, when a sound clashes with a structure it’s part of, due to dissonance, for instance, the clash will be more obvious when the sounds occur simultaneously.

Placing the sounds at slightly different moments in time can lessen this effect, only suggesting the clash, without letting it occur. The first sound of any structure naturally attracts the most attention, because it tends to signal the beginning of a new event.

Figure 9: When elements coincide with other elements, like the electricity poles in (A), they have to share their attention. If elements occur at different times, they can more easily be perceived individually (B).

10. Movement and Change

This mechanism can be seen as an addition to the mechanisms we have already covered. Everything attracts more attention when it’s in motion, and the faster the motion, the stronger the effect.

A source in motion can’t be temporarily let go of by the brain because the risk that the source will move towards you and become relevant all of a sudden is too great.

Even when a source is stationary, but makes a highly variable sound, you have little choice but to pay attention to it. The variations imply information–like speech for instance–which could be of value. Only when the changes become predictable and repetitive is it possible to shift your attention away from them. You begin to accept them as the new status quo.

Changes can be heard in individual sounds, but also in the overarching tonal and rhythmical structures.

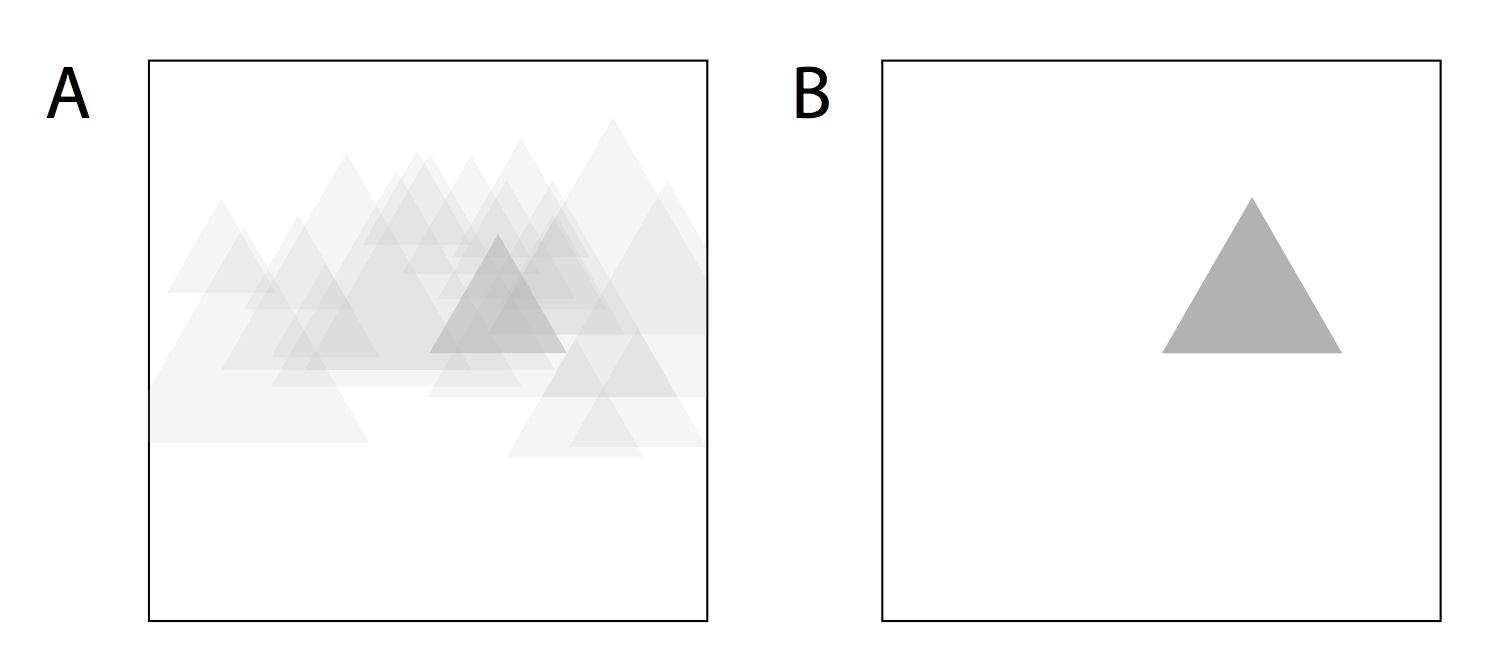

Figure 10: Change attracts attention. But when a change happens gradually, or is otherwise hard to perceive, you can’t reap its benefits (A). By emphasizing the overall structure the change becomes more obvious and more powerful (A’). Change can also happen within instruments (B).

But remember that radical changes can seem like a movie in which the characters are constantly being played by different actors. Especially in compositions that have much variation in what the characters have to say (like many jazz or classical pieces), it makes for a clearer story when you avoid changing their sound and positioning too much. In electronic dance pieces with a lot of repetition, there’s much more room for variation of sound placement and character.

11. Breaking Expectations

While surely not entirely beneficial, people often deal with the complex world around them by relying on some degree of what might be called “prejudice” (literally “pre-judgement”), automated responses to what they perceive, requiring little conscious attention. Fortunately, the expectations you have can also be broken, sometimes to great benefit.

Such a parting with a familiar pathway demands a huge amount of attention, and it can be applied to any expectation surrounding the music you’re working on: Key, harmonic structure, rhythmic structure, tempo, melodic development, arrangement, instrumentation, style, form, lyrics, and so on.

Breaking expectations can also lead listeners to completely tune out, so you do need background knowledge on existing conventions to be able to break them successfully. Usually, you’re looking for a pleasant surprise, something that still bears a close enough relationship to the norm, to prevent the change from scaring listeners away.

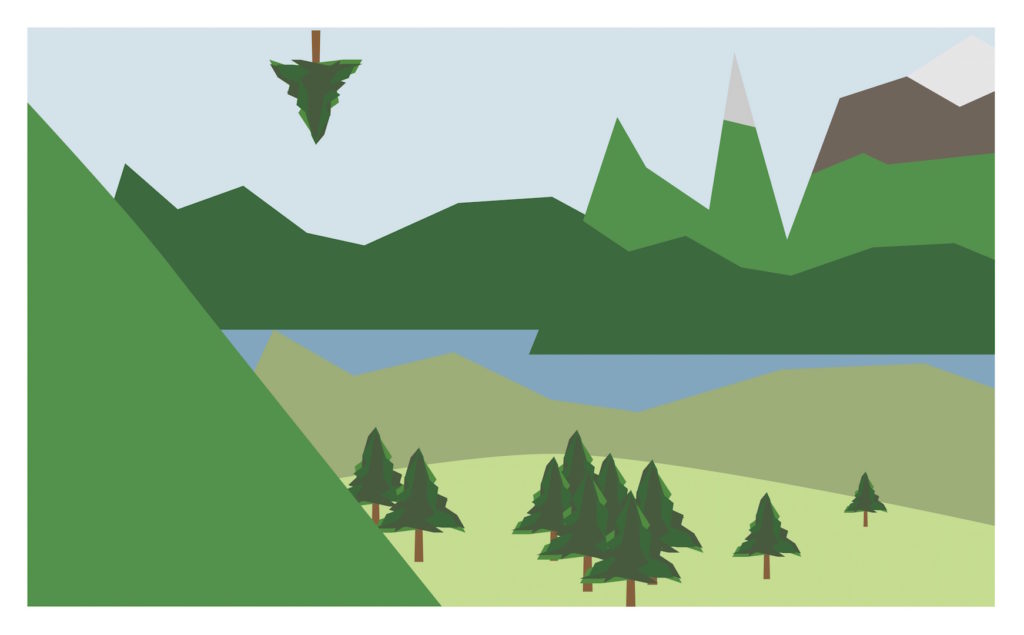

Figure 11: The part of this image that breaks your expectation attracts a disproportionate amount of attention, especially considering how small of a part it is.

12. Embedded Meaning

The second you recognize a sound as indicative of something concrete that you have experienced before (even if it is just something you’ve seen in a movie) an automated response is triggered.

Sounds that have such a concrete meaning attached to them, like the barking of a dog, can be used as literal references in music. While this can be very effective in conjuring a specific image (the numerous gun-cocking sounds in rap songs are a nice demonstration of that—they immediately make for a sordid atmosphere) it can also be counter-productive.

For many listeners, a welcome part of music is that it leaves them free to attach their own meaning to the sounds they hear. The music provides a framework to which you can freely associate and experience the feelings that match your current mood. If you’re confronted with inescapable embedded meanings, it can be off-putting, or at least, narrow the number of paths a listener can take through the music.

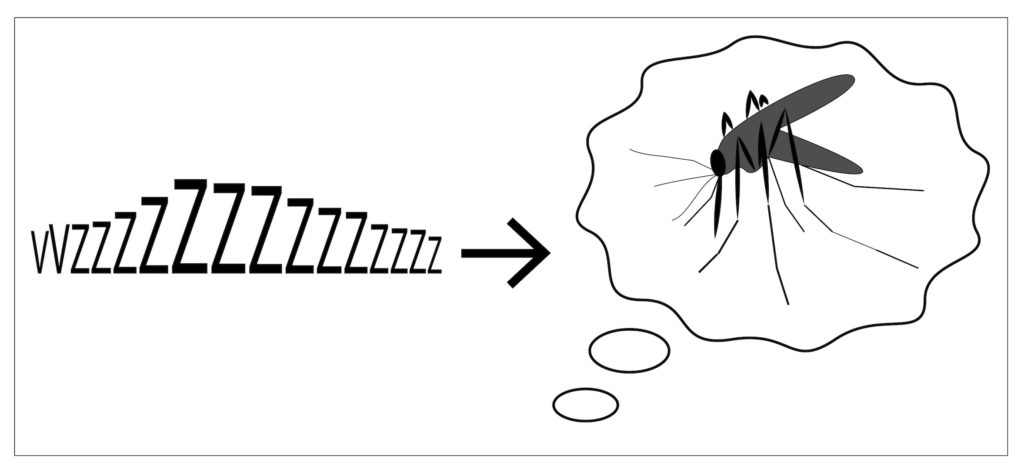

Figure 12: Sounds that have embedded meaning, like in this case the buzzing of a mosquito, can evoke a strong reaction in a listener. She may get annoyed and even start looking around for the culprit.

Using attention mechanisms (what to do with all this?)

You may notice that the amount of attention a sound attracts often depends on how much what you hear resembles what you expected to hear. When you create new music, you probably have a natural instinct to try and play with these expectations. When do you give in to them, and when do you introduce a twist in the plot?

To succeed at this—ultimately, to surprise listeners without putting them off—two things are important:

1) To be aware of your audience’s expectations. (This takes a broad understanding of music in general, and more specific knowledge about the particular styles of music you are tasked with working in), and

2) To design your production in such a way that an audience can learn to appreciate new things along the way.

When you start by introducing a number of familiar sounding building blocks, and then, along the way, create a progressively more unfamiliar-sounding whole out of them, you lure the audience in with something they know , and allow them to gradually learn the structure of the new form you’re presenting to them. If you do it well, they’ll even form new expectations about the structure as they go, which you can later break to surprise them again.

This idea of building on familiar ground and gradually introducing new concepts is a helpful design approach, since it offers a lot of freedom, while suggesting an appropriate starting place. There’s less chance of an audience being put off if you allow them to learn, instead of going for the shock and awe approach.

I once heard this concept at play in the stunning piece “Chicago” by Sufjan Stevens, in which I could here three melodies interweave at the end.

This was only possible because they were each introduced one by one earlier on. if I played the ending in isolation, it became sort of overwhelming and hard to focus on a particular melody. But in context of the whole piece, having lived through the progression of the building blocks, the ending made perfect sense and became beautifully rich.

Of course this is nothing new; J.S. Bach had done it ages ago. And so can you, in your own productions.

Wessel Oltheten is a producer and engineer who lives and works in the Netherlands. He is the author of the new book Mixing with Impact.

Please note: When you buy products through links on this page, we may earn an affiliate commission.