Film Scoring and the Studio: Three Secrets to Outstanding Strings

There is no “in” in strings — oh wait, yes there is!

And composer Ariel Marx knew that already. A fast-emerging composer, the NYC-based Marx can play many instruments, but she clearly has a string affinity, deployed most recently on the new film To Dust starring Géza Röhrig and Matthew Broderick. That’s where she wields her mastery of violin and viola via innovative ways, taking them to a sinister space.

A darkly comedic buddy film about a Hasidic Jewish Cantor from upstate New York who obsesses over the death of his wife and her decomposing body, To Dust premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival in April. Populated by nightmares, coffin salesmen, and other ambivalent experiences, Marx found a way to merge horror movie scores and Yiddish folk music influence her work equally.

Those may seem like strange musical bedfellows, but her score is no Frankenstein. Instead, Marx merges the two styles to great effect thanks not only to her stylistic sensibilities, but her sharp studio techniques.

How did she use the studio (not to mention virtuoso violin/viola skills) to initially capture the creepy/calming ambiances she envisioned? From there, Marx gains massive control by creating Kontakt libraries of her playing to attain pure cinematic grandeur. But her sounds range from totally real to real crazy, and if you ever wondered if it was “OK” to turn the FX loose on your strings, Marx gives you permission with her methods. All this, plus she reveals her Secret Ingredient for achieving truly transcendent strings.

To Dust isn’t the only place where Marx’s flair for combining orchestral and rare instruments with electronics is on display. A prolific film and TV composer, other highlight credits include Jennifer Fox’s The Tale (starring Laura Dern, Elizabeth Debicki, Jason Ritter, Ellen Burstyn, Common and John Heard), Sarah Pirozek’s #Like (starring Sarah Rich and Marc Menchacha), West of Her by Ethan Warren, Mariama Diallo’s Hair Wolf (Sundance, SXSW), and Laura Moss’ Fry Day (SXSW, Tribeca).

Now dive into Marx’s studio solutions for To Dust. Even if strings aren’t your thing, you’re about to get much better at deploying them — and plenty of other orchestral instruments — into your next production, whether its for the screen or a Top 40 track.

Check out two sonic examples from To Dust, then dive in:

Studio Solutions: Score Problem Solving for To Dust

Composer: Ariel Marx

The Film: To Dust, Director: Shawn Snyder; Featuring Géza Röhrig and Matthew Broderick

10,000 ft. view — Here’s how Marx communicated with To Dust director Shawn Snyder ahead of writing any score:

“In an ideal world, I would engage the first musical discussions when the film is still in script stage. Of course this is not always possible with time constraints, but that being said, I try to jump onto projects as early as possible so there is ample time for discussion and experimentation.

“In the script stage, all things are possible, and every aesthetic option is on the table. I can dig deeply into the narrative, and hone in on large conceptual broad strokes for the score. These discussions are equally helpful when they are vague (general mood/tone), and specific (instrumentation/thematic preferences); they help lay the framework, and help me formulate ideas for a palette (or several palettes).

Marx got a big head start on the planning for “To Dust,” now on the festival circuit, directed by Shawn Snyder, starring Géza Röhrig and Matthew Broderick.

“With Shawn, I had the luxury of jumping on board in pre-production. We began working together nearly a year before he shot To Dust. I read the script, and we met often to discuss the film, and the possible directions the score could go — we developed a great ease of communication and shorthand.

“Early on, Shawn shared a Tom Waits quote with me that grew to encompass our entire approach to the score: “I like beautiful melodies telling me terrible things.” The film is really a chamber piece, an extremely original and intimate study of grief, and friendship — Shawn knew that he didn’t want an orchestral score, but something intimate, organic, playful — and most importantly, sonically unique.”

The Sound of the Score — Marx composed an unlikely convergence of Yiddish and horror film influences for To Dust:

“While there are deeply tragic, and moving moments in the film, it is at its heart a dark buddy comedy. In this way, the musical palette had to be malleable and cohesive enough to bring both weight and lightness to the film when needed — sometimes in concert, and at other times in contradiction with picture. In this way, we knew the score had to complement this aesthetic — the music needed to be unapologetically raw, quirky, haunting, and disconcerting.

“Early on we experimented with all of the extremes of our palette — some nodded much more overtly towards Yiddish folk music aesthetics, while others towards acoustic, atonal horror. After Shawn wrapped production and I started working to picture, we decided that the score would have the instrumentation of a reduced klezmer band, but not the harmonic language of one.

“Likewise, for the horror elements, I use many techniques associated with horror films, but in small, intimate capacities — a single string rather than a section etc. We ultimately decided on a palette of chamber strings, guitars, bells, flutes, brass, piano, and percussion.”

Studio Solution 1 — Here’s how Marx captured the horror sounds that she envisioned:

“The ‘horror’ sounds in the film are gentle and eerie — sometimes strident and disconcerting, but mostly quiet and undulating —generated from several layered techniques on a single violin and viola.

“For these sounds, I placed the mic very close to my instrument so every detail was recorded — especially the breath of the bow. I often placed my bow quiet high over the fingerboard, and paired sul tasto and flautando techniques with wide vibrato and quivering single note and fingered tremolos to create ever-changing, dynamic textures.

“Additionally, for more strident and aggressive aesthetics, I used artificial and natural harmonics, harmonic glissandi, overpressure and sul ponticello techniques — placing the bow just before the bridge to create a metallic, piercing sound. I coaxed nearly every sound I could from my solo strings — this intimate approach became a study in the emotional depth and breadth of a single instrument — vulnerability and starkness. This same mic’ing approach was used on nearly all of the other instrumental performances. The mics I used were the Audio-Technica AT 4033 and Neumann KM 88i — all of these techniques described above require very close mic’ing, and thus microphones that allow warmth and detail.

Studio Solution 2 — Marx created a Kontakt library of instruments that she recorded, to aid her workflow and creative options:

“Creating my own Kontakt libraries is a way to both expand my creativity and efficiency. It allows me to manipulate my own playing, as well as saves on recording time.

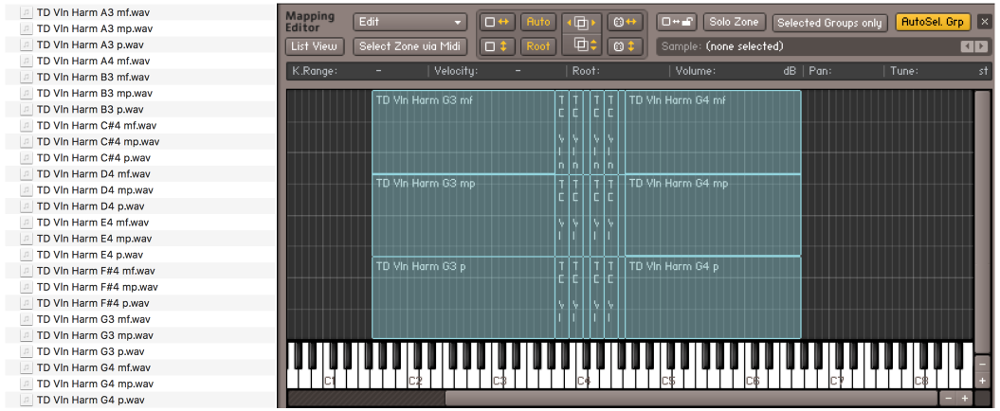

“In a very simple example below, there is a single note motif I play on the violin. In order to sample this, I recorded this motif diatonically in two octaves — starting from G3 to G4. With this gesture, I was able to use the same sample for two chromatic notes, and thus pitch shifting the sample by a half step.

“With this particular sample, half-step pitch shifting did not compromise the realism of the gesture. However, sometimes it’s better to sample yourself chromatically, so you maintain the highest fidelity of timbre for each note, as well as the nuance of different performances.

“You’ll see that for the highest (G4) and lowest (G3) samples, I have dragged them two additional octaves. This transposes the samples drastically, and often times creates distinct and intriguing — and most times unrecognizable — timbres to experiment with.

“Additionally, I recorded each performance at three different dynamic levels (p, mp, mf), which are then assigned to different velocity ranges. Therefore, if I hit D4 at a velocity of 45, I will trigger the D4 sample played at a the softest dynamic. I will then save this Kontakt instrument and use it in my templates.

“I then have much more creative control of this iconic motif — I can process it with audio FX, as well as midi FX such as arpeggiators and modulators, and am not limited by key or range. I can push my violin beyond what’s playable, and thus create an entirely different sound while still preserving the nuance of human performance.”

Studio Solution 3 — Marx is a master of layering live strings. Here’s when to do it, and how to pull it off with realism:

“I will often layer live strings with string samples for two main reasons:

“When the film budget won’t permit a recording session with a live string section, there are creative workarounds that still allow me to achieve the cinematic grandeur that a large string section evokes. If I’m going for realism, I will record a string quartet, and in my mix, I will treat each voice as the principle of their respective sample string section.

“In this way, the human, expressive quality of the live strings sits just above the sampled strings, adding the detail, crispness, and virtuosity that sample strings often lack. I then blend these together with several reverbs and EQs.

“Another favorite layering approach is somewhat more experimental, and for scores where orchestral ‘realism’ is not the intended effect. I will often play a solo violin line, and then process it with varying audio — usually stereo delays, tremolo, various modulators, and lots of detailed parameter automation. I will then mix this performance, as well as an unprocessed performance, and pan them oppositely. I will then layer these with unprocessed string samples to create a nuanced, surging, palette that is both familiar and unusual.

“Layering live instrumentation with samples is a great reminder to always push myself beyond what my sample libraries can achieve. It is easy for composers fall into the trap of writing what sounds best on their sample libraries.

“Having a live player, even just one — be it myself or another performer — brings the vital humanness back into the palette. Even if I process the audio recording beyond recognition, the nuance of live performance is invaluable, and even more so when paired with the hugely impressive and inspiring sample currently libraries available.”

To All You Composers Out There…

“While we all have access to the same incredible hardware and software — we have to develop our own voices as composers.

“In my specific case, so much of my voice as a composer is inextricably tied to my own voice as a performer. It’s very easy to just compose entirely in the box, but I often find that the most inspiring material emerges when I make the most of all of my resources — both with sample libraries and in live performance by myself or instrumental collaborators.”

— David Weiss

Please note: When you buy products through links on this page, we may earn an affiliate commission.