How to Enhance Expressiveness in a Mix

This is Part 2 of a new series on mixing by Wessel Oltheten, author of the book Mixing with Impact.

If you encourage performers to adopt an even greater dynamic range when recording than they would use live, you end up capturing the huge differences in sound texture that go along with these dynamics.

Recently, I wrote a post about the importance of expressiveness in any great music production. Artists will often bring a good deal of expression to a performance— though they may need a producer’s coaching to bring the right level of it to the type of production at hand.

Once you have recorded a strong, expressive performance, some of the musical phrases may need a little bit of help and enhancement to more deeply engage the listener. That’s what today’s post is all about: the exact methods you can use to coax more expressivity out of a part to make it even more evocative and memorable.

Enhancing the expression in an already-recorded performance may seem like a lot of work, but it goes hand in hand with all the mixing you’re doing anyway. First, you have to adopt the right focus. If you’re basing your decisions on the performer’s musical intent, you’re bound to influence expression in a meaningful way. If you’re just going by technical indicators like an even frequency balance, or quantized “correctness” of time and pitch, you’re more likely to undo some of the recorded expression instead of enhancing it.

To be able to answer the question of whether a deviation from perfection is “right” or “wrong”, you have to analyze it musically and compassionately. When you find out that a singer’s expression is unique because of the pitch bends she applies to all of her shorter notes, perhaps you’ll start seeing them as intentional and as strong points and stop worrying about how “off-pitch” these notes look on a screen.

When you listen like a music fan instead of a technician and notice how the late arrival of a particular beat is actually a good thing in terms of phrasing, you may even emphasize this quality by making the beat stand out more—instead of clicking on that “quantize” button.

Almost everything you do in recording and mixing affects musical expression, for the better or for the worse, so it is a good idea to look at some of the means musicians use to express themselves, the methods we can use in the studio to help further shape and enhance their sound.

Timing

Most music has a pulse: a regular time interval between events, that allows a listener to detect the music’s tempo and rhythm. The pulse is what you hold onto for stability. You can synchronize yourself to this pulse, which becomes apparent when you start tapping your foot or bouncing your head to the music.

Not all musical parts have to synchronize perfectly to this pulse or its regular subdivisions in order for you to feel the presence of that pulse underneath. Quite often, individual parts are timed differently in relation to the main pulse: some may be slightly rushing, others may be dragging, some may be straight down the middle, and some will even vary their timing for effect. These variations can be used to bind phrases together, to separate one phrase from another, to create tension, to exploit a sonic spot with less overlap from other instruments, to modify the impression of speed or intensity, or simply to find space to breathe.

The more a note deviates in time, from its expected location and from other notes, the more attention it attracts. This obviously has its limits. If a note is too far off, it attracts so much attention that it becomes a distraction and creates confusion about where the pulse is. But as long as you bring elements together in a way that maintains a clear pulse, there is quite some room to play with.

Gradually slowing down within a phrase makes for a more round, closed statement. Rushing certain parts of the beat gives the sense of a higher intensity and tempo; a greater sense excitement and urgency. Besides timing the onset of notes, you can also vary note duration and the amount of connection or separation between notes. Playing legato will bind notes to form a single musical “word”, while playing the same notes staccato will give the impression of multiple words.

Pitch Trajectory

A musical key is nothing more than a set of expected “pitch possibilities” that you’ve learned through exposure and convention. These pitch possibilities act much like the the pulse and its subdivisions in rhythm: they are stable-sounding “anchors” for your ear. Just like with timing, you have a degree of freedom when moving between these anchors. Transitions between notes can be fluently gliding (portamento) or instant jumps. This allows you to bind or separate musical vowels in both time and pitch. In conjunction with articulation, these are the main tools for phrasing.

Even when a note has arrived at its destination in terms of pitch, there are some possibilities to make it more expressive. For instance, by not landing dead on the anchor, but slightly higher, a note can attract more attention and even separate itself slightly from the chord it is part of.

A performer can also make a pitch “arc” in such a way that it hits the anchor on average but is sometimes just above or below it. This can be done rapidly (vibrato), helping the note attract more attention. Just like with timing, there’s a limit to these variations. As soon as the main structure becomes unclear—if the audience doesn’t get which pitch the performer intends to hit—it becomes a distraction and sounds “off” rather than “interesting”.

Amplitude Trajectory

Most notes don’t start and stop instantly. A note’s amplitude trajectory is called its “envelope”, and this dimension offers some nice ways to give the same note a different meaning. For instance, playing a staccato phrase not only means shortening the notes, but also emphasizing the onset (attack) of the notes, making them ‘bite’. This highlights the difference between the previous note’s ending and the next note’s beginning, separating them even more. In legato phrasing, it works the other way around: by using a soft note onset and pronounced sustain, the amplitude contrast between notes is lessened.

Within a note, the envelope can also fluctuate periodically (tremolo), which can help a note attract more attention—much like using vibrato, but without the shift in pitch. On a larger time scale, amplitude differences can emphasize a particular musical vowel, word or sentence, much like emphasis in speech.

Timbre Trajectory

While the envelope tells you something about the development of a note’s intensity over time, real notes are even more complex than this. Sounds tend to develop in each of their constituent frequencies differently over time. To examine what is happening, you could split up a sound’s envelope into multiple frequency bands. The resulting collection of ‘spectral envelopes’ can show you how the sound’s frequency composition (timbre), develops over time.

Some of these characteristics are fixed, but many can be influenced by an expressive player. For instance, if you adjust the shape of your mouth while singing a note, you can dynamically alter the timbre without changing the envelope. The difference between singing an O, E, A or I is due to frequency filtering within the mouth. This can be controlled separately from a note’s onset or level. Also, as you gradually sing louder, you produce more harmonic overtones, making the sound seem sharper. Many instrumentalists can use similar mechanisms to change the timbre of each note as it develops.

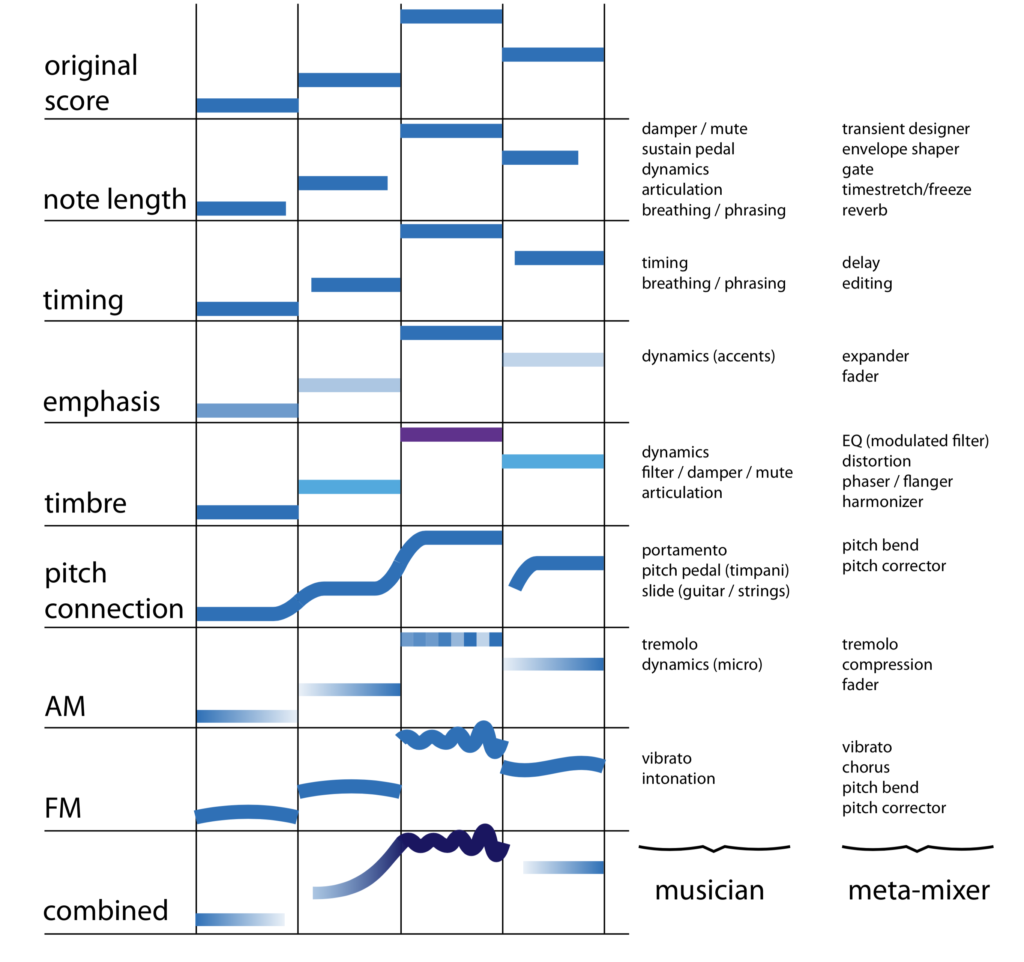

The figure below lists how musicians and “meta-mixers” can use the means of expression, and shows how they relate. I’ve coined the term “meta-mixer” to describe anyone who plays a studio setup as expressively as a good musician would play her instrument. In order to do so, you often need to control multiple parameters simultaneously, just like a good musician does.

Different means of expression and the ways you can use them acoustically as a musician (left column), and electronically, as a ‘meta-mixer’ (right column). The colored bars can be seen as MIDI notes on a piano roll editor, starting with the original four quarter notes at the top, each time showing what a particular means of expression would mean for these notes.

Meta-Mixing

The main challenge for a meta-mixer is deciding what to enhance, what to add, and what to leave alone. As a general rule of thumb, I only start adding things that weren’t there if a part lacks expression even when listening to it in solo. Otherwise, I try to build on what is already there. Instead of adding a vibrato effect on top of a vocal, I can highlight and enhance the acoustically recorded vibrato using pitch manipulation software. Or I can increase existing contrasts between notes using dynamics processing, which can make staccato more staccato and legato more legato.

There is one parameter I haven’t mentioned yet (because acoustic musicians can’t control it dynamically), and that is spatial positioning. Electronically, this can be used to great expressive effect, but watch out not to create too much confusion in terms of placement. Overdoing it in this dimension can make a mix hard to digest for a listener—who is not used to hearing the acoustic space morph in everyday life.

Dynamics are also a concern. When you play back a recording in a car, on transit or in a living room, there’s less room for the large fluctuations in level that might occur at a concert. You still want to make sure the intent of this dynamic information cuts through however, even at consistently medium or soft playback levels. This means artists can’t rely on raw volume changes as much to express themselves in recordings, and need to rely on different ways of keep things exciting.

However, you can still make use of dynamic performances in the studio. If you encourage performers to adopt an even greater dynamic range when recording than they would use live, you end up capturing the huge differences in sound texture that go along with these dynamics.

Once you even out those dynamics using compression and fader automation, you end up with a performance that can change character quite radically, without it changing too much in level. This can give the illusion of dynamics, without their impact being lost at low playback levels.

A rainy afternoon without deadlines to make can be well-spent on doing some experiments to increase your expressive abilities as a meta-mixer. Some exercises I’ve been thinking of lately include:

– Finding creative and musically pleasing ways to alter timing after the fact. For instance, automating the tempo on a non-synchronized delay or sequencer to enhance a sense of movement.

– Trying to get a loop of white noise to “talk”, just by modulating a set of filters. What kinds of filters work best, and what are convenient ways to operate them expressively?

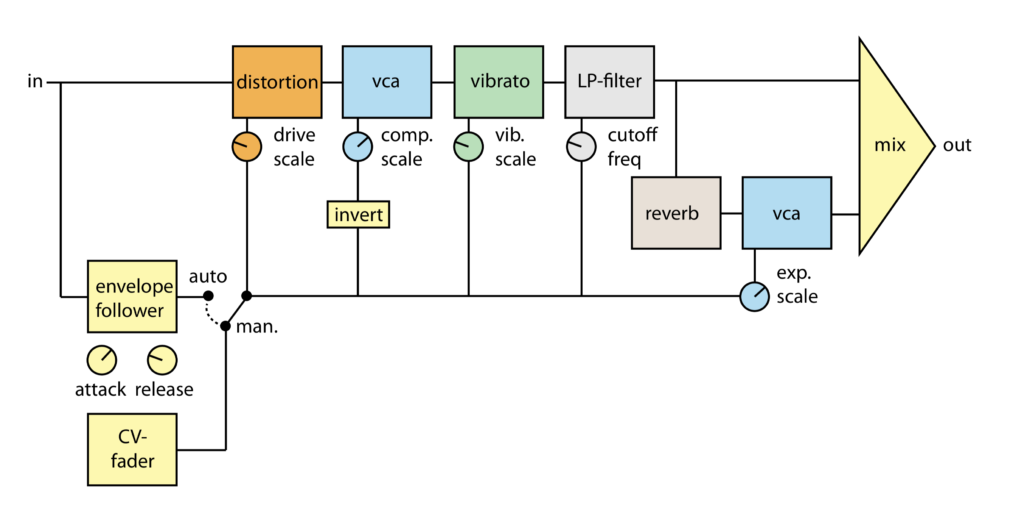

– Coming up with “meta-effects”: single controls that can adjust multiple parameters at once for complex movements in sound. Wouldn’t it be great to simultaneously add distortion, decrease the level to compensate, open up a lowpass filter and increase the amount of vibrato and reverb at once— and be able to automate these effects all in one go?

An example patch to add expression on multiple levels. The intensity of the processing can depend on the incoming signal level but can also be controlled manually with a single fader.

I find that doing these experiments opens up my horizons and thinking when it comes to mixing. When you have a large arsenal of expressive processing at your disposal, you can start to think more freely about the ways your goals could be achieved.

When you notice that the power in a rapper’s expression is in the placement of the consonants, perhaps you’ll treat his voice more like you would normally treat drums—using transient designers, parallel compressors or expanders to manipulate articulation. All performers make choices when it comes to expression—whether they are conscious of it or not.

Good mixers and producers must do the same. Your means of control over expression can be conventional, such as riding a fader on a vocal, or cutting-edge, like developing your own meta-effects. You can use the parameters of expressive control to add new nuance to a performance, or to highlight what is already there. You can even just use an awareness of the elements of expressivity to inform your editing and pitch correction.

However you approach the enhancement of expressivity in your own work, a little bit of conscious awareness of the building blocks of expression, and curious consideration of how they can be used is sure to help improve your craft.

Wessel Oltheten is a producer and engineer who lives and works in the Netherlands. He is the author of the new book Mixing with Impact.

For more great insights into both mixing and mastering, try our full-length courses with SonicScoop editor Justin Colletti, Mixing Breakthroughs and Mastering Demystified.

Please note: When you buy products through links on this page, we may earn an affiliate commission.