Inside Adele’s “25”: How Tom Elmhirst Mixed a Masterpiece

This is where it all comes together.

The official crossroads for the rest of the world are about 40 blocks uptown in New York City’s Times Square, but the current center of the audio universe is at Electric Lady Studios on W. Eighth Street. That’s where mixer Tom Elmhirst is operating, helping the world’s most selective artists make musical magic.

The latest indication that Elmhirst’s mixes are right on track can be seen on top of the charts: Adele’s 25 is breaking records of all sorts as it remains firmly perched on the pinnacle. Since its release on November 20, 25 has sold 5.98 million copies in just four weeks, while the lead single “Hello” has been #1 for eight consecutive weeks.

Anyone who’s listened to the record in its entirety can see why the response has been so rabid. It’s organic and advanced, soulful and strong, groundbreaking and classic all at once. Adele’s voice is at the center of it all, with the power to move listeners in new ways – she is intimate, aching, haunting, primal and embracing on 25. She’s a larger-then-life pop star who somehow still seems accessible on spellbinding tracks like “Hello,” “Remedy,” “River Lea,” and “Sweetest Devotion.”

Adele’s talents are expanding beautifully in scope since the multiplatinum success of her 2008 debut 19 and the six-time Grammy-winning follow-up 21. But Adele didn’t craft 25 on her own: she collaborated with a who’s-who of producers to write and record it, including Danger Mouse, Samuel Dixon, Paul Epworth, Greg Kurstin, Max Martin, Linda Perry, Ariel Rechtshaid, Mark Ronson, Shellback, The Smeezingtons, and Ryan Tedder.

With all these brilliant minds in the mélange, pulling everything together at the mix phase was critical. Who better to do it than Elmhirst, who was chosen to mix nine of 25’s eleven tracks (“Send My Love” and “Water Under the Bridge” were mixed by Serban Ghenea). His past successes mixing for Adele on 19 and 21 made Elmhirst a strong candidate, and his 2015 Grammy Album of the Year” for Beck’s Morning Phase didn’t hurt his chances either.

Add in recent highlights like U2’s Songs of Innocence, Jamie XX In Colour, Mark Ronson’s Uptown Special, and David Bowie’s ★, and it all adds up: Tom Elmhirst is on a roll. Hits are coming consistently through the faders of his Neve VR72, but there’s no formula – every album and every artist are different. Read on to get inside the head of a mixer who’s undeniably at the top of his game.

ELECTRIC LADY STUDIOS, NEW YORK CITY

Your setup at Electric Lady goes beyond just the control room – you’ve got a spacious live room with couches, another lounge that houses your edit station, and two different roof decks. Why is all this beneficial to your mixing?

Artists appreciate the environment that they’re working in, so I put a lot of thought into the atmosphere here. It’s also important to have a space where people can make calls, or do some edits or record additional overdubs, etc. I’m conscious of the fact that when people come into the control room, all we’re focusing on is the mix.

The vast majority of my work are album projects, but there’s usually something else that needs to be worked on while I’m mixing a track.

In this day and age, they’re so many people recording bits and pieces of music all over the planet, on all kinds of formats. So when i start mixing the multitracks have all been assembled. I don’t want to be mixing and realize I’ve got the wrong drums! All the mix-prep happens next door, but its also a nice environment to hang out in and get away from the intensity of the control room.

What makes mixing an “intense” exercise for you?

It is intense, especially depending on the artist. The way I approach mixing records for an artist – whether it’s their first or their tenth album – I give the same level of performance.

When I work with an artist and it’s their first record, that’s their whole life up to that point. That’s a big deal. They haven’t made a record before.

So I have to be more considerate. They don’t know exactly what to expect, and to a new artist a big studio like Electric Lady with all it’s history can be an intimidating environment. I want to make them feel comfortable here. They have to be connected to the environment so they’re happy and productive.

What do you think it is that makes them feel intimidated?

The intensity — mixing records is kind of like delivering a baby. Someone asked me what I do for living the other day, and I said I’m a midwife of audio (laughs)! Artists get a body of work together and deliver it – they’re committing to something. Mixing is very much where you have to make some big decisions. You have to commit. The way records are made these days, 100% in Pro Tools or another DAW, you’ve got endless possibilities, but with the mix, you’ve got to finalize the idea. Some artists find it easier to commit than others, some need gentle persuasion. Some need pushing a little bit.

As a mixer you’re as much of a sound engineer as a social worker, a kind of therapist. People skills are massive in that respect. Being able to take broad comments from an artist and translate them, that’s always been a big part of the job. I’m trying to reduce the stress around what is already a very intense environment. It’s about making the environment welcoming, making sure they have whatever they might need, and not letting anything technical get in the way of that.

Look around you: It feels like you’re sitting in an apartment. It doesn’t look like a studio, that’s my goal. Because on the whole, I find a lot of studios can be quite cold. This definitely isn’t that. I like being here, and everyone I’ve been lucky enough to mix with enjoys coming here.

BECK

Beck’s Morning Phase surprised a lot of people, both for its unique sound and its critical success, winning the 2015 GRAMMY Award for Album of the Year as well as the coveted engineering GRAMMY. How did you come to mix this album?

Beck… Where do I start? He’s just an amazing guy. Absolutely a lovely guy to be around.

He called me one day and said, “I keep hearing records I like, and I keep finding out that you mixed them.” I’m a big fan of Beck – I’ve been listening to his records from the beginning, and when he said, “Do you want to mix my record?” I said, “Yes!”

Beck is pretty meticulous. He’s got an incredible ear, and all his records from an engineering standpoint have sounded amazing. He’s an engineer’s artist – he really gives a shit about how his music is presented: He would go to ten different studios to find out where to track drums. He’d rent a studio just to use the chambers and the plates. He really cares about the engineering, and he’s probably got the best set of ears I’ve encountered since I’ve been doing this.

But the process wasn’t always fast. I mixed the album with him in about three weeks. He happened to be playing some shows on the east coast while we were mixing, so he would pop in and out listening to the mixes. Then we did changes over a period of about three months with my former assistant Ben Baptie. He wasn’t in a hurry, and we were going back and forth on changes while he was touring South America. It was just a really enjoyable experience – I got to know him really well.

What was it that made Morning Phase so different?

There’s something spiritual about it. The song I remember, “Wave,” is the simplest one, just him and an orchestra. His father did the string arrangements, so it’s just Beck and his dad.

He spent a long time recording these songs. It took him a while to assemble the band, just to get these great players in a room together. You need great musicians, great performances, and then Beck, which doesn’t hurt.

How were you personally challenged by the mix for Morning Phase?

There’s a lot going on. It sounds simple, but it took a lot of work to get it sounding that simple, if that makes sense. There’s a lot of layers to that record.

How does a mixer to do justice to a project like that – what’s your practical advice in such a situation?

Get the best possible musicians and use the best possible equipment to make great recordings. It was just great engineering by Darrell Thorp on Morning Phase. Literally everyone involved in that record did their part to the highest ability.

What we didn’t do with the record is rush it, although I do like to work quite quickly to get a sense of performance from a mix. The worst thing you can do is let it go stale, or overmix it.

Because I was a fan I had a sense of connection with him, which was beneficial. I knew his back catalog pretty well. I thought what he wanted to do and what I like doing as a mixer fit really well.

People talk about mixers having a sound. I don’t want to have a sound, but I want to have my sensibilities fit the artists. That’s important: You want to feel a connection as a mixer with the material.

What’s the common thread between the artists you’ve mixed for – icons like Adele, Amy Winehouse, and Beck?

The River Neve: Elmhirst’s VR72. (Photo by Kenneth Bachor)

An uncompromising vision and very clear artistic identity. Incredible performances and originality in their output: they’re not shaped or affected by other artists. That’s what we gravitate towards as a listener.

I think a lot of artists sometimes feel that the people around them get in the way, or sabotage their work. Making records is a collaborative process so my purpose as a mixer is to not get in the way of their vision, but enable it. It’s not my record. It’s their record. It’s really important that we remember that. Making records is hard-core: You’ve got to write it and record it and then stand behind it on tour for two years. Have you ever played on a stage in front of 15,000 people? I haven’t… its probably terrifying.

The other night I was at Radio City with Adele, she had the whole building on the end of a piece of string. Very, very powerful. I aim to match their level of commitment when I’m mixing.

So that happens in the studio as well?

Yes, in the mix there’s a certain moment where you just feel inside it. That’s going to sound really hippie, but that’s what happens. I’ve had that experience when mixing certain songs, where you stop thinking about what you’re actually doing. You forget what you’ve got to do on Monday morning, or your tax bill or whatever. You’re living right in the present. It’s exciting.

That’s what an artist’s job is, be it painting or making music, right? To help us escape the banality of this planet sometimes. I get that from music, and so do a lot of others. Someone else asked me another time, “What do you do for a living?” I said, “I’m in light entertainment, we get people to work and back home.” You see people with their headphones on in the subway, right?

You can do the same with music – capture someone’s imagination and take them somewhere. Done right, the album has the power to move people.

ADELE

Adele and her team had her choice of mixers for 25. After 19 and 21, why were you still the right choice to be mixing her?

There’s quite a small team around Adele and has been from the beginning. I was lucky enough to have mixed some of her most popular songs right from the start (“Chasing Pavements,” “Rolling in the Deep”, “Someone Like You”). There’s a relationship and trust that forms over time, so it was a natural progression for my involvement.

Having so many different producers and co-writers on 25, there needed to be someone who could bring it all together.

How is that beneficial to an album?

When you’ve got lots of different producers/co-writers, it makes sense to have one person mix the record to keep things consistent. There were multitracks coming from all over the place. It wasn’t until quite late in the mixing that we knew exactly what would be on this record.

I started mixing 25 at Capitol Studios in Los Angeles, and then we took it here to Electric Lady Studios.

What was the communication you got from her camp to get started on 25? What did you discuss – and what didn’t you discuss?

I was in LA to mix a record for an Australian band, and then I was actually going to have a vacation! This was early August. Its also quite a unique situation in that I share management with Adele, so I knew they were getting ready to mix. That was the end of my vacation! I ended up working the whole month on the record. Once the productions were ready to be mixed, we started getting multitracks from all over the place.

Did they give you direction?

No, But I had heard rough versions of most of the songs about a month before I started at Capitol in LA

Multitracks then started appearing in no particular order. Sometimes Adele would still be finishing vocals on a song in London, so we were getting new parts all the time.

“Hello” was the first song I mixed. I just got on with it. (“Hello” producer/co-writer) Greg Kurstin and his team sent parts to my assistant, Joe Visciano, and we were up and running!

“HELLO”

How would you characterize Adele’s voice as an instrument now?

She’s got more control. She’s four years older, so it’s matured. Her range is greater. She’s got much more ability to hold back now at times, because she knows she can go further. That’s the thing across the whole album: She’s got a better mastery of voice as an instrument and she’s got confidence. That’s the thing you notice with an artist as they develop.

What was the workflow for mixing “Hello?”

The initial mix was done at Capitol Studios in LA on a Neve VR 72, which is the same console that I’ve got here in New York. We made further changes back at Electric Lady in September.

When I’m mixing the record, there’s the initial mix, which I then print back into the computer, and if there’s changes from there then they’re all done in the box. Once I’ve done the A/D process, I want to stay “D.”

How do you and your team lay out your multitrack in Pro Tools?

The multitrack actually appears pretty simple. I’ve got a system of how they’re laid out, what decisions are made, how it gets to me in a control room. It’s then a very quick process for me to look at a multitrack, getting it up on a console and start mixing.

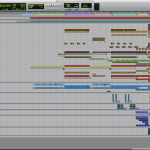

The layout in Pro Tools is essentially the same as how I lay out the tape strips on the console. It’s always drums first, then bass, guitars, keyboards, and then the vocals come last. Adele is in blue and you can see the verse, and the chorus. There’s a different de-esser and some hard notch EQ on the chorus.

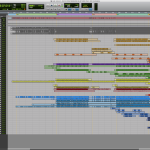

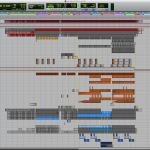

(Click on the below gallery to see screenshots of Elmhirst’s Pro Tools session for “Hello”):

- Multitrack Master of “Hello” (This is the session that Elmhirst was working off while mixing). Cleaned, color, coded, and fits on one page.

- First Stem Session. “After I print stems, we make a new session with all the stems that were printed. Same color coding and format so its easy to get around. Each vocal effect was printed separately to make changes easier.”

- “This is the final session before files were sent to mastering. Verse 1 starts with a seperate instrumental and Acapella then switches to the master. All the changes are done along side of the master using phase and reverse phase to make changes in volume or EQ. You can also see Emile’s additional instrumentation in Orange.”

- Adele lead vocal in-the-box plugins before being sent to the Neve 1066>1176 Bluestripe>Fairchild 660.

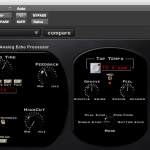

- Soundtoys’ Echoboy used on the toms in the second verse.

- Eventide Blackhole used on some reverse guitars going into sections.

What was the vocal chain you set up for Adele on “Hello?”

The chain in LA was the Neve 1066 (Mic pre/3-band EQ) to the Bluestripe UREI 1176 compressor into a Fairchild 660 limiter. I’m taking the multitrack return from Pro Tools to the line amp on the Neve 1066, then straight into the 1176 and 660 and back up the insert return.

The UREI is hitting and releasing quicker, while the Fairchild is doing a much slower attack and release. Here at Electric Lady I use a Neve 1081 into a Blackface 1176 and then into a Tube-Tech CL 1B compressor.

A large part of the vocal sound is the plates and chambers at Capitol Studios: There’s chambers that Les Paul built back in the 1940’s, and they are literally like nothing else on earth. When I got back to NY in September, I mixed five or six songs at Electric Lady, so we’d send the vocals from here and they’d record it through the chamber, and send back the prints.

Once you’ve found the vocal sound for someone like Adele, you want to use it through the whole record, and these plates and chambers sound incredible. To get to them is hard enough: you go in to the basement of Capitol, you then climb through a ladder to get to the sub-basement, where it looks like no one has been for 50 years. You literally open a hatch and climb down a steel ladder.

Have you ever been in a reverb chamber? They’re like tiled rooms, not painted – like Alice in Wonderland rooms, they don’t look right.

There’s a lot of effects going on behind the vocals. There’s an AMS delay, an Eventide preset called “Canyon,” a plate, a spring…You can see the escalation of things. There’s about seven or eight things going on. You get this wide kind of thing, but her vocal remains super-present.

So what’s going on in the box?

There’s no compression processing going on at all, just some de-essing and some little volume draws on the vocals – little dots and dips, but no rides. The rides have been done with automation on the flying faders.

What role did the piano play in the mix?

Obviously, it’s in Adele record. It’s got her name on it, so the vocal will be the most important thing. Because I mixed “Hello” first I didn’t really know it at the time, but I could start to see there was a theme with piano throughout the album.

When you’re looking at the principal elements of a mix in the song, invariably it will be the vocal and a principal instrument – piano, guitar – and I had to keep the theme sonically with the vocal. Does that make sense? I’m getting different recordings, they use different microphones, and obviously some days she sings different from other days in different countries over a period of a couple of years.

What were some other evolutions that happened for “Hello” during the mix?

Because of the longstanding relationship I have with Adele, I had some license to experiment and I had my friend Emile Haynie come in during the mix. He produced part of Lana Del Rey’s [eponymous] first album, and did “Runaway” with Kanye West – he’s a wonderful producer and songwriter. He ended up adding some additional rhythmic elements that complemented the production. Adele and Greg liked it, then there were a few email exchanges to get it sitting right.

I don’t add things to mixes just for the hell of it. If I add anything, I better be confident it’s needed. But what’s the worst thing an artist can say when you play them something? “I don’t like it!” So you take it off, no big deal. My skin is thicker now: 10 years ago, when people said they didn’t like something in my mix, I would take it personally. I don’t anymore, we are all on the same team and there is a sense of purpose to the collaboration.

In addition to the percussion which comes in on the second verse, there’s a rhythmic sound we added which is a loop going through an Eventide H3000 plugin with a panning and filtering flange nature to it, plus a Soundtoys Crystalizer plugin.

MONITORING AND MORE

How does your control room environment factor into the way you mix?

At the later stages of the mix, I’m at the back of the room listening – I’m not at the console anymore. It’s much easier for me as a mixer to step back from it, and let Joe operate the computer. Then I can make really quick creative decisions about it.

The ATC SCM 50’s and an ATC SCM 1-15 subwoofer have been my main monitoring for three years now. They’re the best I’ve had. I also have Auratones 5c’s — $14 worth of speakers (laughs). If I can hear more frequencies then another mixer, I’ve got an advantage, simple as that.

Its just as important to hear a mix on an iPhone speaker as it is to hear it on high end monitoring in a control room. It’s got to work on everything. It doesn’t matter what speakers you use, as long as you know how your speakers sound, you can get the results you need

I know this room like the back of my hand, and that’s the biggest asset for any mix engineer, the room and the monitoring. This is the best-sounding room I’ve ever had, and I’ve worked 20 years to get a listening environment like this.

But I don’t want it to be overrun by technology, I still want it to be comfortable. There’s a lot going on in this room – a hell of a lot – but it’s done really well and discreetly.

How does your Neve VR72 console fit into your workflow now?

Musical mosaic (Photo by Kenneth Bachor)

I really tried to keep it simple. There’s still balance. I still get all my music out of 24 channels, and I’ve probably never used more than 40 channels on the console.

I’m still mixing how I mixed when I started: I like mixing on a console because I can touch things, its a tactile experience. I can make a lot of changes very quickly.

THE MAKING OF A MONSTER HIT

Why are people responding so massively to 25, and the lead single “Hello?” Did you expect that?

No, not to this level. I don’t think there’s another voice out there like this at the moment. She’s a traditional ‘50s balladeer, but a modern-day Sinatra – a modern-day crooner that writes her own material.

And the lyric for “Hello” is so sharp, it’s very relatable – anyone can react to that: “It’s so typical of me to talk about myself, I’m sorry.” That’s brilliant, it’s self-deprecating. She’s not saying, “I’m the best thing ever,” it’s, “I’m flawed.” She sings about her flaws. She sings about these things that are so personal. To accept your flaws and write about them is very brave and vulnerable.

That’s one reason why, during the mix, I thought the verse of “Hello” should be intimate, drier and more conversational. It’s clever what she’s doing as a songwriter: She’s having a conversation, but she’s the only one talking. It’s nostalgic in theme so the listener can personalize it quickly.

HAVE YOU EVER MIXED EXPERIENCE?

“Hello “can be heard absolutely everywhere right now. What’s it like for you when it comes on in a coffee shop?

I enjoy it in a different way. Its moving to know that so many people have a connection to something I worked very hard on.

You’re in the midst of a career stage that any audio professional would want to achieve. How do you see yourself changing as a mixer?

I’m getting better. I’m still just as interested as I was when I first got into it. I’m lucky to be working with some of the biggest artists out there. I’m having to rely less on technique. Mixing is just so much more intuitive now. I’m quicker at getting where I want to get. When I have an idea, I can get to it – whether or not I fully achieve it is another thing!

I’ve basically stacked the odds in my favor: I’ve got the studio of my dreams, the best monitoring environment, and two great engineers that work for me so that all the prep is done before I get the multitrack. And I’ve got great artists to work with.

So all I’m actually trying to do as a mixer is to not fuck up – I’m just limiting the possibility of things going wrong. That gives me the best opportunity to get things right.

— David Weiss

Please note: When you buy products through links on this page, we may earn an affiliate commission.

Jake Antelis

December 23, 2015 at 3:38 pm (9 years ago)Great interview thanks!

sleepd

December 27, 2015 at 10:16 am (9 years ago)Genial, but this tells me nothing about how he mixed the Adele tracks. I appreciate his resume and his philosophy about studio setups, but with the title this article was given, I expected to read about his choices for compression and nuanced reverb and when he applied such decisions. Did he group his percussion tracks or leave them separate? Analog summing? Didn’t get any of that. #fluff

RustiCapeTown

December 29, 2015 at 1:30 am (9 years ago)Just shows that you clearly don’t understand the mental requirements of a mixer or producer. What an absolutely self centered comment. Why don’t you bring your own personality and sound to your clients. Don’t try just take free, quick advice from a legend. He worked hard to get where he is!

Ricardo Wheelock

December 30, 2015 at 4:55 am (9 years ago)I couldn’t agree more RustiCapeTown

jo

February 11, 2016 at 6:07 am (9 years ago)yup

Brian Lucey

April 4, 2016 at 7:43 pm (9 years ago)Exactly right. Tom told you everything that he can tell you. The rest is little details, totally up to you, and really, doesn’t matter at all.