How to Sample Music Without Getting Sued: The Curious Case of the Most Controversial Copyright

Using samples—snippets of someone else’s copyrighted material in your music—can be a bit of a legal grey area, but for years artists from nearly every genre have done it.

One of the first examples can be traced back to 1956 and the novelty song “The Flying Saucer” by Buchanan and Goodman. It used clips from 18 different chart toppers from 1955 and 1956, as well as a spoken “War of the Worlds”-style news report about a flying saucer.

Using samples in music may be part of American culture and history. But so is suing over it. Sampling lawsuits are almost as old as sampled music itself. Read on to learn how to stay safe from litigation on your own releases.

Since there was no precedence for sampling, Buchanan and Goodman made an agreement with the publishing houses involved to cut them in on a share of the royalties. Everyone involved was happy. Other artists however, haven’t been quite so fortunate.

Most music fans may recall “Rapper’s Delight” by The Sugarhill Gang as the first popular use of sample-based music, but that’s not actually quite right.

Instead of building their track out of samples of “Good Times” by Chic, Sugarhill Gang hired a group of session musicians called Positive Force to record the primary backing tracks, but this approach still resulted in a copyright lawsuit.

Sugar Hill Records eventually settled out of court and agreed to give the original writers of “Good Times” songwriting credits on future releases of “Rapper’s Delight”.

Toward the end of this post, we’ll go through a simple and easy checklist to help ensure you won’t find yourself on the wrong end of a copyright suit if you do choose to use samples in your work.

On the way there, we’ll take a look at the captivating legal history of sampling, through a few of the most important and formative cases in copyright history.

From Open Secret to Opening the Checkbooks

Sampling didn’t become widely popularized until the 1980s. As audio technology became more affordable, artists began making records using drum machines, synthesizers, and samples of instrumental breaks in old soul, funk, and disco records.

One of the most popular of these samples was The Amen Break, a 4-bar drum solo taken from the song “Amen, Brother” performed by The Winstons in the late 60s. (Ironically, the recording itself is actually a cover of Jester Hairston’s traditional gospel song “Amen”, which was originally popularized by The Impressions in 1964.)

Since the 1980s, the Amen Break has been sampled over 2,000 times. It’s been used in countless genres, and even “spawned several entire subcultures” However, every single use of this sample has been done so without regard to copyright.

According to Nate Harrison’s Can I Get an Amen, neither the drummer nor the copyright owner have ever received any royalties or clearance fees for the use of the sample.

Richard Spencer, The Winstons’ bandleader, feels that the ubiquitousness of The Amen Break is equal parts “plagiarism” and “flattering”.

Although copyright law holds that artists must obtain approval to use sampled material in their own tracks or face potential suits, there are countless similar cases where this has not been done, with mixed results.

A Turning Tide

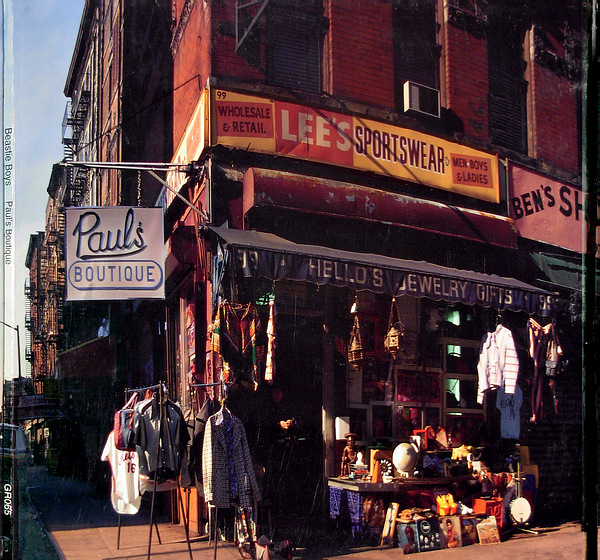

In 1989, The Beastie Boys released their sample-based masterpiece, Paul’s Boutique, which is said to have used as many as 300 samples.

While they obtained clearance for some of the recordings used on the album, many of the original artists were uncompensated and no clearance was obtained.

Could an album like the Beastie Boys’ Paul Boutique be made under the copyright norms of today? Some artists are testing that question.

The Beastie Boys got lucky and weren’t sued over the album until 2012. Ultimately, the courts ruled that the plaintiff, TufAmerica, could not claim damages, but only because they lacked standing to sue.

According to Billboard‘s Eriq Gardner, the ruling was “not because the samples were fleeting or because the critically-acclaimed Paul’s Boutique represented a transformative use of copyright material, but rather because TufAmerica never acquired an exclusive license to the copyrighted material.”

In short, it’s not that The Beastie Boys were declared innocent, just that the only company that bothered to try and sue them didn’t technically have the right to do so.

By the 1990s however, record labels had started seeing the opportunity for profiting by licensing copyrighted material to other artists, and by protecting themselves against unauthorized uses.

In 1990, M.C. Hammer released “U Can’t Touch This”, which relied heavily on a sampled baseline from Rick James’ “Superfreak”. After the resulting lawsuit, Hammer settled out of court with James, and ultimately had to do more than just clear the sample. In no position to bargain after the release had already come out, he gave James co-composer credit and a cut of the royalties as well.

That same year, Vanilla Ice released “Ice, Ice, Baby.”, which sampled the baseline from Queen and David Bowie’s “Under Pressure.” Ultimately, Ice also wound up giving songwriting credits to Bowie and Queen to avoid legal action.

The writing was on the wall:The era of sampling first and asking questions later was quickly coming to an end thanks to litigious copyright holders. In 1991 we saw the final nail in the coffin, the case of Grand Upright Music v. Warner Bros. Records.

Alone Again

Grand Upright Music v. Warner Bros. Records

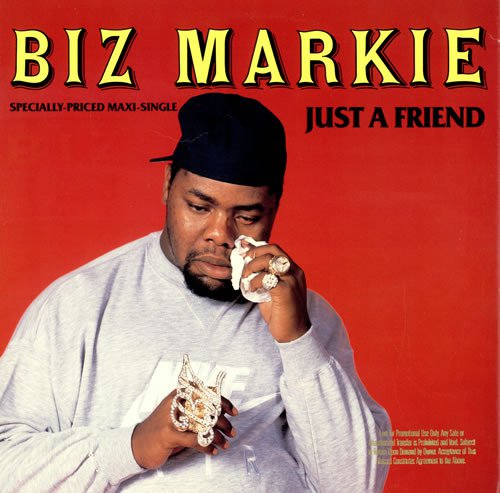

Biz Markie found to the hard way that in US copyright law, artists and other copyright holders have the right to refuse the use of a sample.

In 1991 Biz Markie released a song on his third studio album, I Need a Haircut, called “Alone Again”, which used an unauthorized sampled of Gilbert O’Sullivan’s “Alone Again (Naturally).”

Markie’s label, Warner Bros, had actually reached out to O’Sullivan in an attempt to obtain clearance for the sample, but he refused. Naturally, Biz decided to use the sample anyway, which the courts held made their infringement “knowing and willful“.

Despite their efforts to convince the jury that sampling was commonplace in hip-hop music, and that this should excuse the use, the courts ruled that sampling without permission is copyright infringement, and that any future uses of samples must be pre-approved by the original copyright owners to avoid a lawsuit.

With one bang of the gavel, the norms in the music world were changed forever.

Copyright holders began demanding up to 100% mechanical rights to recordings, which limited artists to using fewer samples. Clearance fees skyrocketed, which prevented independent artists from using samples at all. For instance, if Paul’s Boutique were released under today’s strict copyright laws, it has been estimated that The Beastie Boys would owe as much as $20 million in royalties and fees.

Markie’s case, named Grand Upright Music v. Warner Bros. Records, made it effectively impossible for most artists to release a record like Paul’s Boutique today. According to Matthew Yglesias of Slate, “It’s neither logistically nor financially feasible to contact hundreds of separate artists to win permissions for a complicated, sample-based album. And record labels don’t want to take the risk of exposing themselves to hundreds of potential lawsuits.”

Exceptions to the Rule Emerge

In 1990, a case similar to Biz Markie’s involving 2 Live Crew had begun, but it wouldn’t be resolved until it reached the Supreme Court four years later. The Crew were being sued for copyright infringement on their 1989 song “Pretty Woman”, which was created as a parody of Roy Orbison’s classic “Oh, Pretty Woman.”

Like in Biz Markie’s case, 2 Live Crew’s management actually contacted Orbison’s camp to obtain a license, but Acuff-Rose Music refused to grant it. 2 Live Crew released the song anyway, and the following year, after the record had sold nearly 250,000 copies,

Acuff-Rose sued 2 Live Crew and its record company, Luke Skyywalker Records, for copyright infringement. (Ironically, the name of their record label was eventually changed due to an infringement claim from none other than George Lucas.)

The District Court agreed with the defendants that the song was a parody, and therefore made protected “fair use” of the original song under the Copyright Act of 1976.

However, the Court of Appeals reversed this decision, arguing, in part, that their making money off the parody negated the fair use claim. By 1994, the case had gone all the way to the Supreme Court, who reversed the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals decision, and determined that “Pretty Woman” was not copyright infringement, and was indeed protected by the fair use defense.

This was exactly what musicians needed: A loophole. A creative workaround for incorporating copyrighted recordings in their music. It sparked a revolution that rippled through genres, cultures, and time itself. Artists started sampling copyrighted material in transformative ways under the potential protection of Fair Use. That protection however, has not yet been fully put to the test.

What is Fair Use?

The Copyright Act of 1976 states that use of a copyrighted work may not be considered copyright infringement if it qualifies as “Fair Use”. In the act, this is described as a use “for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research.” It also outlines 4 factors for judges to consider:

(1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

(2) the nature of the copyrighted work;

(3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

(4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

The 2 Live Crew set the precedent that not all four of the need be fulfilled if the new work is sufficiently, transformative, meaning that the new work considerably adds to the original or turns it into something new.

Although many recording artists may be prepared to demonstrate this defense, few have ever actually had to use it. There’s never been a sampling lawsuit in which the defendant claimed fair use that has reached the decision stage. In every single case, the defendant has settled or negotiated out of court, usually before the recording is even released.

Joe Fassler of The Atlantic writes that this is “because the case would probably go all the way to the Supreme Court, and it would cost hundreds of thousands of dollars to get to a decision. It’s a much better financial decision to go ahead and work out the licensing deal before the record’s released.”

Or, in the case of Danger Mouse, you could potentially take your chances and just release the record without working out a licensing deal at all…

The Grey Album

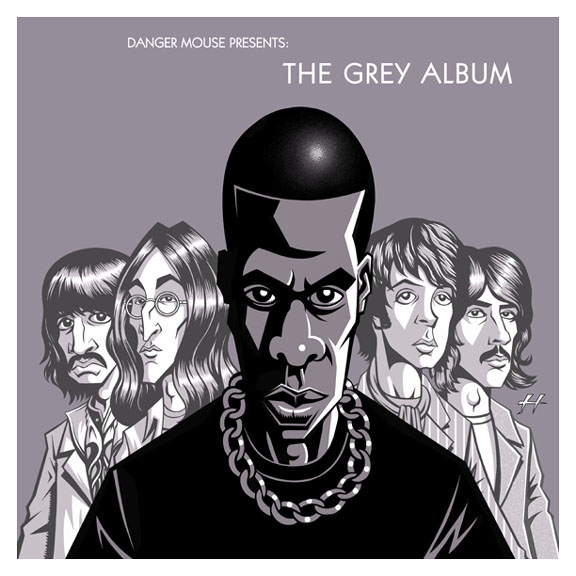

Danger Mouse’s Grey Album pushed the boundaries of US copyright law. Though he managed to avoid facing a lawsuit due to pressure applied against the copyright holders through social media, Danger Mouse was never able to give the album a proper commercial release.

Danger Mouse’s The Grey Album combines tracks from Jay-Z’s The Black Album, and The Beatles’ White Album.

Even though Jay-Z, Paul McCartney, and Ringo Starr all expressed their approval of the album after it made news, EMI and Capitol Records (owners of the Beatles’ White Album) ordered a cease and desist on distribution of the album early on, claiming that Danger Mouse (also known as Brian Burton) never requested clearance for the samples.

However, Burton was living by the old adage of “it’s better to beg for forgiveness than to ask for permission.” If he had asked EMI for permission to use the samples, they could have said no, bringing the project to a halt.

Even if they had said yes, according to Popular Musicology Online, in order to obtain clearance from the various copyright owners, Danger Mouse would have to negotiate license fees and royalties with the a dozen or more copyright owners, including EMI and Capitol Records (owners of the sound recordings on the White Album), Sony Music and ATV Publishing (owners of the compositions on the White Album), The Beatles, Apple Corps Ltd., as well as Harrisongs and Wixen Music Publishing (owners of George Harrison’s compositions), Roc-A-Fella Records (owners of the sound recording for the Black Album) and the owners of the compositions on the Black Album. Phew. That’s a lot of permission.

Even if Burton were to obtain clearance for all of the samples used on the album, the licensing fees and royalties may have been astronomical. According to attorney Fredrich N. Lim “most small artists such as Burton cannot afford the exorbitant fees required to sample copyright works of well-known artists.”

And that’s not to mention the royalties. It’s not uncommon for copyright holders to request upwards of 50% of publishing rights. Considering how many artists were involved, Burton may have had to pay out more in royalties than he might have been making.

In response to EMI’s cease and desist on distribution of physical copies of The Grey Album, activist groups convinced several websites to offer free downloads of the album for 24 hours as a form of protest. Over 100,000 copies were downloaded on “Grey Tuesday.”

Aside from a few more cease and desist letters to the websites hosting album downloads, no further legal action was taken, but The Grey Album never received a proper commercial release.

Night Ripper

Girl Talk joined Danger Mouse in testing copyright norms, and also narrowly escaped a full-blown copyright suit. Under legal pressure, Night Ripper was dropped by its physical and digital distributors.

A few years later, another artist pushed the boundaries of the Fair Use defense. In 2006 Gregg Gillis, better known by his stage name, Girl Talk, released his third studio album, Night Ripper, which was almost entirely comprised of samples. The 16 track album sampled over 164 different artists, all in the name of “transformative use.”

Gillis does not seek sample clearance from copyright holders. If he did, his albums would likely never had been made. David Post writes in The Volokh Conspiracy that “it would take you hundreds of hours of work and hundreds of thousands of dollars to clear the rights to this album even if you wanted to.”

Although iTunes and Gillis’ CD distributor both stopped carrying Night Ripper due to legal concerns, he claims he’s never been threatened with a lawsuit. Some believe it may not be in the interests of copyright holders to sue Gillis for infringement. In addition to the likelihood of bad publicity—as evidenced by the response to the Grey Album release—if the courts ruled in his favor, it would be a precedence-setting judgement for the Fair Use defense, and could compromise their ability to collect royalties from other artists in the future.

Responding to a reporter from The New York Times, Representative Mike Doyle, Democrat of Pennsylvania, offered that “case law gets built as cases are brought to court, and I think that more case law is going to fall on his side as this becomes more mainstream.”

However, not all lawyers agree with this prediction. In the very same piece, Barry Slotnick, head of the intellectual property litigation group at the law firm Loeb & Loeb argues that “fair use is a means to allow people to comment on a pre-existing work, not a means to allow someone to take a pre-existing work and recreate it into their own work. What you can’t do is substitute someone else’s creativity for your own.”

But some artists feel that copyright law has gotten so restrictive it actually impedes creativity. Gillis himself has said “What the Beastie Boys and Public Enemy were doing, no one could do anymore.” Another landmark copyright case from 2005 had already proved that statement to be true.

100 Miles and Runnin’

(Bridgeport Music, Inc. v. Dimension Films)

Way back in 1990 N.W.A. released an album called 100 Miles and Runnin’, featuring a song of the same name. It sampled a two-second guitar chord from from Funkadelic’s “Get Off Your Ass and Jam”, for which they were never compensated.

The copyright owner, Bridgeport Music brought an infringement case to a federal judge who ruled that the sample was not in violation of copyright law.

Years later, this decision was reversed by the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals, who decried that the copyright owner of a sound recording has the exclusive right to replicate that work. The court put it frankly: “Get a license, or do not sample.”

However, a number of District courts have since rejected this controversial decision. Recently, in the 2016 case VMG Salsoul v. Ciccone where Madonna was accused of illegally sampling the song “Love Break” in her song “Vogue”, a federal judge stated that “We recognize that the Sixth Circuit held to the contrary in Bridgeport Music, Inc. v. Dimension Films, but—like the leading copyright treatise and several district courts—we find Bridgeport’s reasoning unpersuasive.”

In at least this case, a lower court has thrown precedent out the window. Ultimately, the fair use defense remains unproven for non-parody uses, and as controversial as copyright law itself.

Blurred Lines

Can you be sued for sampling without sampling? Maybe. The controversial judgement in the case of “Blurred Lines” brings the safe-haven approach of “sound alike” recordings into question, blurring the line of what is and what is not a copyrightable element of a song.

The most recent, and perhaps the most controversial copyright infringement case in recent years revolves around Robin Thicke, Pharrell, and T.I.’s “Blurred Lines.”

In 2013, shortly after the song’s release, the estate of Marvin Gaye claimed that “Blurred Lines” infringed on Gaye’s “Got to Give It Up” by copying the “feel and sound” of the song.

In what Rolling Stone’s Erin Coulehan called a “preemptive strike,” Thicke and co. sued the family of Marvin Gaye for making an invalid copyright claim since “only expressions, not individual ideas can be protected,” and “a ‘groove’ or ‘feeling’ cannot be copyrighted, and inspiration is not copying”.

Although Thicke admitted that “Got to Give It Up” was the inspiration for the song, he believes they did not infringe on the copyright:

“Pharrell and I were in the studio” he told GQ, “[and] I was like, “Damn, we should make something like that [‘Got to Give It Up’], something with that groove.” Then he started playing a little something and we literally wrote the song in about half an hour and recorded it.”

Pharrell claimed the two songs are “completely different… just simply go to the piano and play the two. One’s minor and one’s major. And not even in the same key.”

They seemed to have a good case, because traditionally, it has been held that only melodies and lyrics can be copyrighted. (Distinctive elements like basslines that rise to the standard of being “melodic” may also be protected by copyright.) You can copyright a specific work of creative expression, but not a chord progression, a form, a feeling or an “idea”.

There is however, also some precedence for successful lawsuits over “copycat” recordings. For instance, when Tom Waits refused to allow his music to be used in a car commercial, the company hired a singer to do his best Tom Waits impression instead. He sued and won. (More than once. He even successfully sued Frito-Lays over a Doritos ad that employed a Tom Waits impersonator.)

After two years of legal battles, a jury found Thicke and Williams (but not T.I.) liable for copyright infringement, and awarded Gaye’s family $7.4 million in damages.

Thicke and co. believed the verdict was due to “a cascade of legal errors warranting the Court’s reversal,” and filed an appeal with the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals in 2016. More than 200 musicians signed a petition in support for the appeal, stating that “the verdict in this case threatens to punish songwriters for creating new music that is inspired by prior works.”

In March 2018, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled to uphold the original verdict that “Blurred Lines” infringed on “Got to Give It Up.”

It was, and still is, a controversial judgement. The decision was not unanimous. Judge Jacqueline H. Nguyen said the decision “allows the Gayes to accomplish what no one has before: copyright a musical style” and “establishes a dangerous precedent that strikes a devastating blow to future musicians and composers everywhere.”

Though technically not a case of using an authorized sample, the “Blurred Lines” ruling shows that the approach of recording your own “Sound Alike” versions of a song to avoid having to clear samples may not save you from a lawsuit in the end.

Needless to say, the laws for sampling are murky and contentious at best. If you intend to use copyrighted material in your music in any way, it’s always safest to obtain clearance from the copyright owners.

With that in mind, here are a few simple steps you can take to protect yourself if you choose to use sampled musical cuts in your work.

How To Clear A Sample

In order to get clearance for a sample, you’ll need to get a license from two sources:

- the copyright owner of the composition

- the copyright owner of the sound recording

In some cases, both copyrights may be owned by the artist. Or, they may be owned by two separate people, such as a publisher and a label.

Because there is no compulsory license for samples copyright owners can charge any rate they wish for a license, or refuse the use altogether. The rate you will pay to use for a clearance to use a sample usually depends on things like the success of the original, the length of the sample, the likely success of your new work, and how integral it is to the new composition.

Copyright owners may ask for a flat fee, a percentage of the royalties, or even co-ownership of the new composition. It all comes down to what you (and they) can negotiate. Because the copyright holder can potentially flat-out refuse to license their material to you, you may want to seek clearance before you even get started incorporating a sample into a production in a significant way. (Unless of course, a few years in court on a copyright crusade that you may or may not win sounds like your idea of a fun time.)

To contact the copyright owner of the composition and request a sample license, search the database on their PRO’s website for the title of the song. ASCAP, BMI, and SESAC all have search options. The copyright owner for the composition should be able to point you in the direction of the owner of the sound recording, so this approach will often kill two birds with one stone. If not, start by contacting the record label.

Lawyer Up

Distributing music with unauthorized material—no matter the length of the sample—is technically copyright infringement. Even if you release it for free.

To protect themselves, most record labels and distributors include “warranty clauses” where you agree that your music doesn’t contain any unauthorized material.

Unless you want to go all the way to the Supreme Court to prove your fair use claim, it’s certainly a copyright violation to use someone else’s recording without permission. However, it may not be a violation to make a recording that sounds just like the original, although the recent “Blurred Lines” ruling casts some doubt on this approach.

Up until very recently, it was largely assumed that if you did not imitate copyrightable parts of a song—like its melody or lyrics—you could record your own “sound alike” version and avoid the need to clear a sample. (You’d just need to pay mechanical songwriting royalties if you used traditionally copyrightable parts of the composition like you would with a cover song.) But this whole cottage industry of “sound alike” recordings may have just been turned on its head because of the “Blurred Lines” ruling.

Ultimately, pursuing copyright infringement is up to the copyright holder. In some cases, it may actually behoove the copyright holder to let the infringement continue. If a YouTube star covers a song in a viral video, it could be the biggest opportunity for exposure the songwriter has ever had. (Though a lawsuit could be one of their biggest opportunities for a payout in the short term.)

In any case, it’s often better to be safe than sorry. When in doubt, it’s always best to contact an entertainment lawyer in your state for legal advice. And if you do decide to go through the expense and uncertainty of trying to take your case all the way to the Supreme Court, let us know about it so we can cover it in these very pages!

Brad Pack is an award-winning audio engineer and writer based in Chicago, IL. He currently owns and operates Punchy Kick, a professional mixing and mastering studio that specializes in pop punk, emo, punk, grunge, and alternative music.

He has been helping artists connect with fans through emotionally resonant mixes, cohesive masters, and insightful guidance for over 10 years. Check out his website PunchyKick.com or say hi on Instagram @PunchyKick.

Please note: When you buy products through links on this page, we may earn an affiliate commission.