Audio for VR and Games is Changing—Here Are the Latest Trends

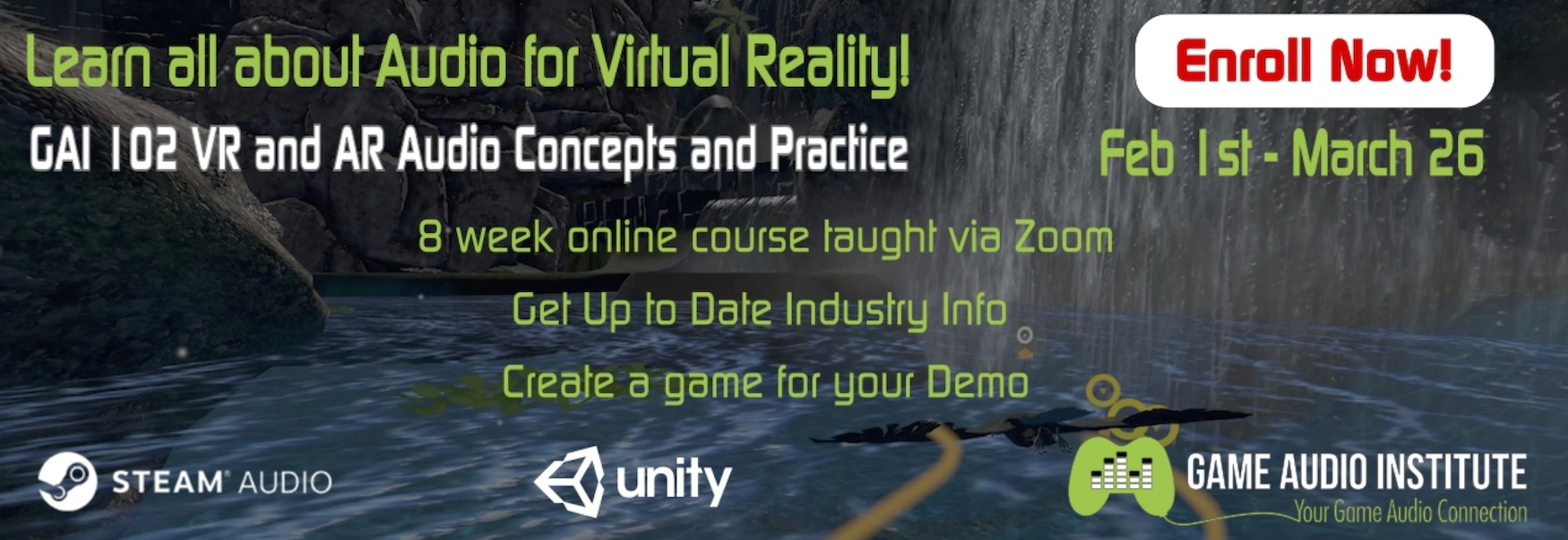

(Author Scott Looney is a game audio education pioneer and Co-Founder and CTO of the Game Audio Institute (GAI). The next GAI course, “VR and Audio Concepts and Practice in Unity” runs from February 1st-March 26, 2021. Visit here for more details.)

In game audio, it’s important to keep up on the latest developments; the industry is always changing as new technologies are adopted and old ones are dropped.

This is never more true than in the fast-growing and dynamic field of what is being increasingly regarded as “XR”, where the ”X” can mean ”Cross” or ”Extended”, or even ”Expanded”. That’s right—the term is so fluid, nobody knows what it even means.

Although there’s been previous periods of hype and buzz over this technology, this latest round got its kickstart (quite literally) in 2012 when Palmer Luckey ran a Kickstarter crowdfunding campaign to produce the first developer version of the Oculus Rift, a VR headset. The shattering success of this led to the purchase of Oculus by Facebook in 2014, and with big companies like HTC (in collaboration with Valve) and Sony who had already been experimenting with VR, entering the market.

By the start of 2017 the big three VR devices selling at the high end were the Oculus Rift CV1 ($600), The HTC Vive ($800), and The PlayStation VR ($300). There was a low end of the market as well, which was smartphone based, and here another large tech giant, Google, jumped in in 2014 with the Cardboard, an inexpensive viewer for VR that you could insert any cell phone into and experience a basic version of VR.

This inspired many developers to try making simple VR-based games. At a slightly higher price point came the GearVR, a collaboration with Samsung debuting in 2015. Using this and only your smartphone, you can connect to a special version of the Oculus Store to purchase apps and experiences.

Early Spatial Audio Tools In Game Engines and 360 Film

So let’s discuss what audio technologies were available for VR devices during this time. Probably one of the most exciting things was that 3D-oriented audio took a significant jump from where it was only a few years ago. Spatial audio began to be utilized more and more, most specifically Head Related Transfer Function (HRTF) audio and ambisonic audio together, which could create convincing surround experiences in headphones for game players. This was a perfect marriage for someone wearing a headset to experience VR.

Oculus was the first to create its own spatial audio system which was relatively simple, offering both spatial positioning as well as ambisonic file playback and limited room reflections, but little else.

Two Big Ears, a startup focusing on a similar spatial audio system called 3Dception, became very popular with game developers. By May 2016, it was acquired by Facebook which in turn dropped all support for game engines and interactivity to turn it into 360 Spatial Workstation, one of the only free systems for spatial audio production for 360 films. This was run as a plugin in popular DAWs like Pro Tools, Reaper, and others.

Shortly afterwards, another startup called Impulsonic, with a similar product called Phonon, had barely been established before it was acquired by Valve, who rebranded their product as Steam Audio. This toolset had many more capabilities than the more bare bones approach by Oculus, including partial occlusion and custom surface materials to get more accurate sound propagation, reverberation, and reflection, though initially ambisonic file support was limited. Support for Unreal Engine was added later as well.

Last and most significantly, Google was impressed with the popularity of the Cardboard and smartphone VR in general, and decided on creating a competing product to the GearVR for Android smartphones called Daydream. Amongst all of the technologies to support this, they created what would eventually become known as Google Resonance, an efficient spatial audio system with much of the features of Steam Audio, plus better ambisonic playback support.

It’s important to note that all of these described toolsets are free to use and are employed in commercial games or 360 film—no license fee is required. There are many others out there, more often for 360 film than games per se, such as Dear VR, Auro3D, and others, but these are paid plugins and not freely available to use and publish.

It’s important to note that all of these described toolsets are free to use and are employed in commercial games or 360 film—no license fee is required. There are many others out there, more often for 360 film than games per se, such as Dear VR, Auro3D, and others, but these are paid plugins and not freely available to use and publish.

That Was Then – This Is Now

So what has happened since this time, in roughly three years? To some extent, the lofty hype surrounding some aspects of the XR field has descended a bit, as marketing promise collided with actual usability:

Of the three high-end headsets we described at the start of 2017, only one, the PlayStation VR, is still being sold, though it’s getting a bit long in the tooth at this point. Sony did announce that the PlayStation 5 will support the now five year-old technology (at least) of PSVR, which is certainly better than them dropping support, but not much of a move forward.

Facebook has gradually started to direct Oculus’s development priorities and positioned them at the lower end of the market, starting with the 3 degrees of freedom (head rotation only) wireless Oculus Go, and then resulting in the Oculus Quest (with 6 degrees of freedom [rotation and position]) and more recently the Quest 2, an even lower cost and higher performing device. Accordingly the tethered headsets like the Rift CV1 were discontinued and the newer Rift S is following suit, as its sales have been fairly lackluster amid the enthusiasm for the standalone devices.

HTC is still making tethered headsets (with the exception of the Vive Focus, not available in the US still), but discontinued the original Vive in favor of the more expensive and non-consumer based Vive Pro and Vive Pro Eye with eye tracking. The consumer headset is the Vive Cosmos, featuring inside out camera tracking, similar to Quest, though a faceplate switch can give it better Vive-like tracking with external sensors.

HTC is still making tethered headsets (with the exception of the Vive Focus, not available in the US still), but discontinued the original Vive in favor of the more expensive and non-consumer based Vive Pro and Vive Pro Eye with eye tracking. The consumer headset is the Vive Cosmos, featuring inside out camera tracking, similar to Quest, though a faceplate switch can give it better Vive-like tracking with external sensors.

Smartphone VR Is Dead

But the biggest news, affecting audio as well, is that smartphone-based VR is dead. Oculus gradually sunsetted support for the GearVR in favor of the Go and Quest. Google’s Daydream crashed and burned, mainly because users having to use their cell phone inside of the viewer meant that they could not use it as a phone, which caused significant friction, and after an initial flurry of purchases, the sales of Daydream viewers dropped.

Google, well-known for discontinuing technologies in the past, then removed all VR support from Android completely. This also affected all of their supportive toolsets, including Google Resonance, which at this point hasn’t been updated in nearly three years, and Unity removed an included version of it in late 2019. Resonance can still be downloaded and installed into Unity manually, though.

There are now only two free spatial audio engines that are being updated regularly that are used in Unity: Oculus and Steam Audio. The Unreal Engine does have its own spatializer it can use, as well as Oculus Audio and Steam Audio.

This is important to note in comparison with Unity. If you are a developer making a game to sell on all possible VR platforms, including PSVR, you will have to use Unity Audio with no spatialization, or use Sony’s own proprietary system to do this, which means you would have to use two different spatial systems to run your game on all VR platforms. Since Unreal has its own spatializer, it’s not subject to these limitations.

Another important fact is that this type of spatialization running on standalone devices takes up processing power, and these devices are by design less powerful than dedicated laptop/desktop PCs. So developers might choose not to use spatialization due to hardware limitations.

Ambisonic Audio Will Have To Adapt Or Be Used Less

The absence of smartphone-based VR may affect the usage of ambisonic audio in games as well.

If you might recall, ambisonic audio is perfect for situations in which head rotation is tracked, like 360 film, but it cannot track head position currently at all. Smartphone VR-based games for the Oculus Go, Google Cardboard, GearVR, and most Daydream devices only did head rotation, so ambisonic backgrounds at that point could make sense in situations where player teleportation was possible, but locational movement restricted, and since the head was fixed in place it was easier to make this happen.

However with today’s headsets—the vast majority of which can support head repositioning in addition to rotation—using ambisonic audio becomes a more significantly challenging issue, and either head positioning must be restricted by the game designers, or the audio itself needs to be more subtle in nature, acting more like a non-locational ambient background that can potentially shift with head rotation.

There is the performance issue to take into account as well—higher order ambisonic file playback is very processor heavy. And lastly, ambisonic music that tracks head rotation is not likely to be a popular option inside games, though it is possible. Non-headtracked (headlocked) spatial music where the movements of elements are already recorded would be more likely.

Spatializing In Audio Middleware

You might be interested to know how game audio middleware such as Audiokinetic’s Wwise and Firelight’s FMOD Studio dealt with spatializing then and now.

In the earlier time period, the most common method was to simply use whatever spatializing toolset was desired. Since spatialization is essentially last in a signal chain of processing of the audio stream, the output of the middleware banks could simply be routed to the spatializing toolkit of choice in the game engine, using a relatively small amount of code by the middleware company that would route the stream to the spatial library.

FMOD and Wwise both still support this method, but Wwise has recently created its own spatialization system separate from other third party toolsets, and with the recent purchase of Audiokinetic by Sony, it’s more than likely that Wwise’s audio system will work with all VR devices on the market today, including PSVR.

Both toolkits currently support Google Resonance as well, but as time progresses, and unless Resonance itself gets updated, it will likely be used less and less over time.

Where the Market Stands Now

The result of this latest shakeup in terms of devices is that the low end of the market basically is Oculus/Facebook and no competition exists of any significant note. No other tech company is creating standalone VR currently, though there are rumors that Apple is planning something, and other companies have dropped hints in the past.

On the higher-end consumer market, HTCs Vive line is dropping significantly in popularity. PSVR is still being used and developed for, and there is also a new player in the form of the very popular Valve Index system, backwards compatible with older Vive tracking, and including innovative controllers as well.

Additionally, starting in 2017, Microsoft entered the VR realm with less expensive tethered VR headsets manufactured by other companies like Acer, Lenovo, and Hewlett-Packard using its Windows Mixed Reality system, and using Steam VR for tracking. These less expensive headsets have improved in terms of quality and in the most recent HP headset, the Reverb G2, the cost has increased, but also the resolution and tracking performance has improved greatly, nearly eliminating the screen-door effect and god rays that were common in older models. All of these tethered devices can only work with Windows-based computers (except PSVR), and device audio, including spatialized audio, is dependent on the Windows operating system’s ability to handle it.

At any rate, you can see that keeping yourself updated as to platform developments is important to staying relevant in the game audio industry, and having the right skills and knowledge that employers are looking for is essential. The status quo can change radically in a short time.

Note from the author: If you’re interested in learning the latest information about the field of VR/AR audio for games, consider taking our 8 week course at the Game Audio Institute starting on February 1st, 2021. You’ll get a balanced hybrid course with up-to-date information on the entire XR field and the relevant audio concepts driving it, plus in-class Zoom meetings as well as a game lesson that will help you design and implement audio for a VR game. Check out an introductory video to the course here.

Note from the author: If you’re interested in learning the latest information about the field of VR/AR audio for games, consider taking our 8 week course at the Game Audio Institute starting on February 1st, 2021. You’ll get a balanced hybrid course with up-to-date information on the entire XR field and the relevant audio concepts driving it, plus in-class Zoom meetings as well as a game lesson that will help you design and implement audio for a VR game. Check out an introductory video to the course here.

Scott Looney is a passionate artist, soundsmith, educator, and curriculum developer who has been helping students understand the basic concepts and practices behind the creation of content for interactive media and games for over ten years. He pioneered interactive online audio courses for the Academy Of Art University, and has also taught at SAE Ex’pression College, Cogswell College, UC Santa Cruz, City College SF, and San Francisco State University. He has created compelling sounds for audiences, game developers, and ad agencies alike across a broad spectrum of genres and styles, from contemporary music to experimental noise. In addition to his work in game audio and education, he is currently researching procedural and generative sound applications in games, and mastering the art of code.

Please note: When you buy products through links on this page, we may earn an affiliate commission.

[…] In game audio, it’s important to keep up on the latest developments; the industry is always changing as new technologies are adopted and old ones are dropped. This is never more true than in the … (read orginal – story…) […]