Ken Andrews: From Failure to Mixing Stone Temple Pilots’ Upcoming Album

Ken Andrews has always had his own way of doing things.

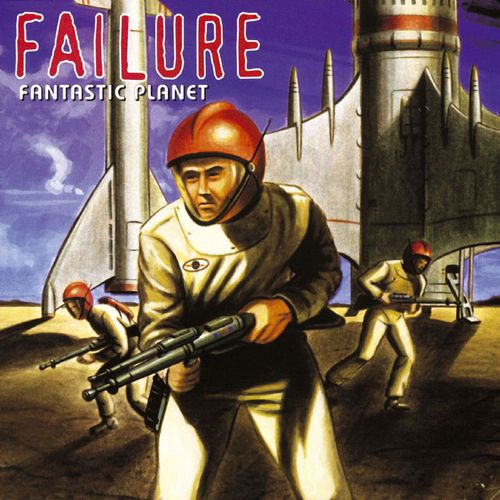

His distinctive sound started reaching a wide audience when he founded Failure, an inimitable band whose albums like Fantastic Planet and Heart Is a Monster have gathered up a dedicated following for their grit, artistry and intellect. While that group has stopped and started from the early ‘90s until today, his own career has had more of an even flow, evolving steadily from performing artist to producer, composer and mixer.

It’s a comprehensive occupational path that has led to plenty of heavy producing and mixing credits, including work with M83, Paramore, Beck, Blink-182, Pete Yorn, Jimmy Eat World, Nine Inch Nails, Black Rebel Motorcycle Club, Blinker the Star, Gone Is Gone, and Citizen. On the soundtrack side, he’s contributed to film scores including music for the motion pictures Oblivion, Nacho Libre, Twilight Saga: New Moon, Tenacious D’s The Pick of Destiny, plus Chris Cornell’s “You Know My Name” theme song for James Bond: Casino Royale.

Operating out of his private LA enclave, Red Swan Studios, Andrews has just put the finishing touches on what promises to be a very high-profile record for 2018: Stone Temple Pilots’ upcoming seventh studio album. As STP’s first release without the late vocalist Scott Weiland, Andrews was tasked with putting their new singer Jeff Gutt front and center.

What makes Andrews up to this heavy challenge? In this interview with SonicScoop, Andrews explains what made him and STP a timely match. You’ll also find his insights on what makes an audio engineer stand out, his simple criterion for selecting a recording studio, and some very helpful tips for nailing the mix.

The first big thing I wanted to talk about was your career and how it’s morphed. For you, it’s moved between being an artist, a producer, a composer, and a mixer. How much of this convergence was planned, and how much of it would you say was unplanned?

I would say most of it is unplanned. I’ve done the artist thing on and off for a long time, and then starting in 1997 is when I produced my first record that wasn’t my own band. But it’s always been peppered with production, and then after I had kids about nine years ago, the production and mixing became a little bit more planned, in the sense that I was a little less interested in doing the artist thing, because it takes you away from home a lot.

As the years went on, things got a little more focused on mixing. People just started hiring me more for that, and it worked out. I enjoy doing it for sure. And now that Failure has rebooted, it’s actually a good mix of things to be in a band making records and writing songs, and then also mixing for other bands.

It’s a little harder for me to produce records because of the time commitment these days. I still do it every once in a while, but the mixing is more conducive to simultaneously doing the artist thing.

Failure rebooted in 2014 after a 16-year break. Was there a moment where you had a realization how much you had changed as a music person, in between those times?

I definitely noticed that I was more efficient and faster in the studio, but surprisingly, at least with the Failure thing, the writing/recording/artist part of it was pretty familiar to the ’90s. We didn’t change too much in terms of how we work together and how we write songs together, and the method of making a Failure record was similar to how we made Fantastic Planet.

But it just went a little smoother because I had a lot more experience with the technical side of things and getting things recorded and, maybe, less mistakes in the studio in terms of recording things. That actually seemed to be really conducive to the writing because I could make the recording process transparent for the band. It was just happening. And as a band we didn’t have to wait around as much for technical things to happen, because I got them going quicker because of all the experience.

Producer Progress

The first artist that you produced after Failure in 1997 was a band from the Midwest called Molly McGuire, for their album Lime. Do you remember how you felt about becoming a producer on that album and, then, for some of the early projects subsequently? What did you like about that role as you start to take it on?

I’ve always loved being in the studio and recording and making records because it’s a very creative process. So it was a little daunting the first time – the first few times – because I wasn’t completely used to having creative input on someone else’s songs. But it didn’t take too long to get used to that.

The other thing was that as a band member, you have to be a bit of a psychologist in terms of how to get along with your other bandmates. But when you’re a producer that’s amplified because you’re expected to help the band get along amongst themselves and with you, plus the technical stuff too. It was all pretty new to me, so it was a little daunting for the first few albums.

What would you say you know now that you didn’t know then, that you would like to go back and tell yourself then about facilitating the creative process? What are some of the big things you learned about how to let the creative process flow, and what are some things that you learned not to do?

The most beneficial thing to do if you want to make records for a living is to just make records, and learn by trial and error because it’s the experience that’s the thing that helps you later on. Being able to realize something’s wrong or something could be better very quickly is something that you really only get with experience.

One of the things I wish I could have done on that record — but it just wasn’t a possibility because they didn’t have the budget — is I really wanted to have a separate recording engineer so I could just produce, and focus on the material with the band and the performances.

I did get the opportunity to do that a little bit later on in my career, and that really helped because it did give me more opportunity to focus on the material, but I also was able to glean some techniques and processes from the person that was engineering for me. It’s nice to get in there and really be focused on the songs.

Is there a way to characterize the ideal relationship between producer and engineer? When you do have an engineer, what are you looking for from them?

If the artist is ready to record and they’re in there ready to go, and the engineer is ready to go at the same time, that’s half the battle right there. Keeping everything moving and not having too much down time for the engineering side of things is really key and helps keep everyone engaged. There’s nothing worse than a technical problem that stalls a session for an hour or more.

That’s not always in the hands of the engineer, but a good one can be ready for stuff like that. That’s the best thing is when I look over at them and say, “Okay. Let’s do this.” They’re already ready.

From Producer to Mixer

Some projects you worked on you only produced, and some you started to mix as well. How long were you mixing for the project out of necessity, and then, how did that transform into being a mixer?

I don’t know if I can come up with a particular album where the tide started changing. I don’t think there’s been that many times, maybe once or twice, where I’ve produced something that I haven’t mixed. Most of the time people hired me to do both from the outset. But if you look at the total number of albums that I’ve been a part of as either a producer, mixer, or both, probably the highest number would be in the mixer–only category at this point.

Was there a specific point where you started mixing only?

Paramore’s self-titled 2013 release, mixed by Andrews, debuted at #1, and featured the GRAMMY-winning single “Ain’t it Fun.”

I would say it’s been an evolution over the last ten years. It wasn’t a dramatic, “I’m not producing anymore.” It was just that mixed in with some of the producing gigs were these gigs where people were just saying, “Well, we already have a producer, but we want you to mix because we like this record you did as a producer and a mixer, or just as a mixer.” And it just was one of those things where it snowballed a little bit on its own.

I actually really liked that because it was a nice change from the longer time commitment of producing a record, where you really have to go in there and join the band for a few months.

And I naturally gravitated towards mixing a wider breadth of music, different genres, basically, whereas I might not be completely comfortable producing more of a straight-up pop album. I actually really enjoy mixing it because I enjoy listening to stuff like that, but in terms of getting into the writing of it and executing the production style of pop with the artist, I might not be the right guy for it. But mixing it, I can really sink my teeth into it. And it’s less of a time commitment per project, so instead of producing one album in two months, I can mix three albums in two months.

That coincided with the evolution of how records are mixed these days, which is they’re not necessarily mixed in $2,000-a-day mix studios in Hollywood anymore because mixing inside-the-box has become so good, sonically speaking, that I could mix from my home studio and have a little bit more personal time, whereas producing a band — I prefer to be in a nice, full-service studio if I’m producing a rock band. And those hours tend to be long because people want to get the most value out of the studio.

Are there studios that would emerge as personal favorites to work in over the years?

Oh, sure! Sunset Sound, I did a few things there, NRG in North Hollywood, Ocean Way if I was producing something. I would generally end up in one of those three studios.

What is it about those studios that make them emerge to you as favorites? What were they getting right on a consistent basis?

It’s mundane, but the answer is “maintenance.” I mean, that’s a big deal. You’d be walking into a room and having pretty much everything working, it’s a nice feeling. Some studios, they can’t afford to have a full-time maintenance person or even a part-time, so you come into a studio and a lot of things aren’t working, and right off the bat you’re having to do a lot of workaround, and it sets a bad tone right off the top.

So I always appreciated those studios because they were booked all the time, and they reinvested in the studios by having good maintenance and good technicians that, if something went down, they could fix it in the shop and have it back to you quickly.

Flying the Red Swan

Today you do most of your mixing today out of your personal facility, Red Swan Studios. Tell me about how it’s set up to serve your needs as a mixer.

Well, it’s boring now, because my mix studio’s gotten extremely pared down to just some Pro Tools hardware and my speakers. It’s crazy. I have a lot of outboard gear, I just don’t use it when I’m mixing. I use it when I record.

The last Failure record [2015’s The Heart is a Monster] I busted out all my equipment and set it all up and used it all. But when I’m mixing now, I’m mixing in the box. So all I need is a room that sounds decent and has the speakers I’ve been using for 20 years now, which are Genelec 1031As. And a powerful computer because I like to have no limit on plugins and processing, so I have a newer trashcan Mac Pro and it’s got a lot of RAM — I’m able to run a lot of tracks and plugins on it.

As time has gone on, I’ve had a lot of different incarnations of my studio in different spaces, and most of it’s in racks that are on wheels so I can transport it easily. But as time has gone on, it’s gotten whittled down to almost nothing now.

You’ve been mixing out of Red Swan for several years now. What do you feel are some of the more memorable mixes you’ve executed there?

Well, off the top of my head there was the last Failure record I did in my own spot, as well as Paramore’s eponymous album [2013’s #1-charting Paramore]. The Beck single “Timebomb” from a few years ago turned out really well, some M83, plus the latest Jimmy Eat World album, Integrity Blues.

I’m really proud of the way Integrity Blues sounds. It was recorded really well. A lot of the records that I work on these days are self-produced because budgets have gotten smaller across the board, so artists have had to tighten things up. But that was a record where the band valued the old-school work flow: They had a producer, recording engineer, they went to good studios, and it really showed in the final output of that record.

Landing Stone Temple Pilots

How did your mix career lead you to working with Stone Temple Pilots on their upcoming album?

The DeLeo Brothers, Dean and Robert, did another band that they were in, Army of Anyone, that wasn’t Stone Temple Pilots. They had Richard Patrick singing from Filter, and a different drummer [than STP’s Eric Kretz], Ray Luzier. I mixed their self-titled album in 2006.

So when they were working on this latest album, Dean called me up and said, “Hey, what are you doing? We’re getting to the mix stage of this album and wanted to see if you were interested.” And I said, “Of course!” And now, I’m doing it. I had already mixed the first single [“Meadow”], which was an audition to get the whole album.

They partnered with Sirius Radio for this album, and I know that they did a live concert where that song was recorded. So that might be out there also.

Why was it a no-brainer for you to say “Yes” to mixing the record? How would you characterize Stone Temple Pilots as a band, their sound and everything about them?

I mean, I’ve been fans of the DeLeo brothers and Stone Temple Pilots for a long time, since the ’90s, and I’ve known those guys since that time. Specifically, I really like the DeLeo brothers as musicians. They’re incredible guitar and bass players. And Dean has been an inspiration to me as a guitar player, for sure, since the ’90s. So it’s a real treat to work with those guys.

What do you think it was that was different that they brought? Why did they get people’s attention, and then keep it?

Because they were good songwriters. They had really good songs and really good guitar parts and sounds and lyrics, and they were the full package. Part of that is they had a lot of experience. They’d been in bands before, and they were seasoned musicians even by the time Stone Temple Pilots had started. Dean and Robert are real aficionados of rock history, and they know how to get everything from vintage guitars to vintage amps and parts. They just know everything about recording rock, basically. So they bring a lot of skills to bear on their projects.

And me, from my drummer perspective, I’ll throw in for Eric Kretz because he’s definitely one of my favorite drummers of all time.

Oh, yeah. They all are. They’re a really good band. And you know what the other thing is? They know what they like. And once you achieve that, you’re there, basically. It’s not a big mystery as to what you’re shooting for. Sometimes the younger bands know they like something, but they might waffle a little bit more, whereas these guys know what they’re looking for.

On that note, I’m going to ask you to speak immodestly: This is a band that knows what they’re looking for, and they’ve sold tens of millions of albums, they chose you as a mixer. What do you think it is about you as a mixer that makes you a good match for them?

It’s a combination of I just get what they’re going for, and I understand where they’re coming from on a lot of different levels. Getting their parts to speak so that you can really hear what everyone’s doing all the time is a real basic thing that you have to achieve with them. But that’s not too difficult to do.

Then, the other thing is a little blurrier, which is just making the song sound exciting and fun and like you just want to hear it again, which is a little hard to put your finger on, and it’s more of a taste thing.

When I sent them my first mix of “Meadow” they loved it. They were just like, “You captured the vibe we were going for. And we were a little worried because the rough mixes didn’t really have the thing we were looking for, and we were wondering if it was there in the recording. But now that we’ve heard your mix, we know it’s there.”

Mixing Tips & Tricks from Red Swan

Is there something you can point to, technically, that you did to help pull that mix together that our readers can execute in Pro Tools while they’re mixing? What’s a tip you can give them?

Wow, there’s so many little tiny decisions you’re making throughout the mix, it’s hard to pinpoint one thing. I definitely think if you know that the band was around when the rough mixes were made, even if they don’t like them, it’s good to just still have those because there were probably some preliminary decisions made from the band’s point of view that you want to know about.

For a lot of bands, the inclination is, “Oh, don’t even send them that mix because we don’t like it.” But I always ask for it. I’ll be able to hear things that I don’t like right away, but it’s more of the things that they decided, like, how featured did they want the vocal to be in the bridge? Because a lot of times bands maybe want to make it more of a background thing, and you’ll be able to hear that intent in the rough. So getting the rough mix and living with that for a little while, at least, is always a good idea.

That’s fabulous advice. You also talked about doing the mix in a way that you can hear everything — is there a technique you can point to that allows you to create space between the sound sources? What are any tips you have for making sure everyone can hear everything that’s going on?

One thing that I do all the time in Pro Tools that is maybe not so easy to do on an analog console – depending on how many channels you have available — but I often break out, say, a given bass track or a guitar track or even drums onto their own tracks for different sections of the song.

Even if they were delivered as one continuous track for the whole song, I’ll go through and cut them all up and put them on different tracks for the different sections, because a bass player may be playing the lower strings in the verses or higher strings or whatever, and then either go high or low in the chorus. You may need to not just change the level, but you might want to attack the whole processing chain a little differently to get that part to really speak because it’s a different part.

I do it with vocals all the time, fine-tuning the mix based on the sections of the song or the parts that the instrument plays. And it’s convenient in Pro Tools because you can – instead of automating all those different things which can be arduous and time-consuming – just duplicate the track, pull the bass in the chorus into its own track, and now you’ve got control of the bass for the chorus part without affecting the verse part.

This is the first album with STP’s new vocals Jeff Gutt. How would you say the band is different with Jeff? And what might you be doing differently on this seventh album with him there as the vocalist, than if it were Scott [Weiland] on vocals?

I don’t think I’d be doing anything different from a mix standpoint, really. He’s got to be there. He’s got to have a light on him. But he’s a good singer, so that’s half the battle. He cuts through naturally, the way he sings.

With STP, though, it is definitely the whole package. That’s especially because all their parts are pretty interesting, and they’ve really thought about their parts, and there’s not a ton of tracks, which is really cool. It’s really about the performance. I’m making sure that what they put into it dynamically performance-wise is still coming out the other end. That’s my main goal.

That’s very well-put as the mixer’s mission. Last question: We’ve talked about so many different ways that you’ve been involved in music, creating and producing it. I’m curious what you, as a listener, would like to get out of the end product, whether it’s a song you’ve produced, mixed, composed, or you’re just turning on Apple Music, a CD or vinyl. What does a great song do for you?

It’s one basic thing: It creates a feeling. And that’s something that, as a mixer, you really have to focus on because the technical stuff doesn’t really get you to a great mix. It can help you, as a tool, get to a great mix, but if you don’t understand the emotional content of the song, you’re not going to be able to accentuate it with the mix.

So I try to turn my technical mind off when I’m listening to music and just feel it, just let it influence my mental mood or state. If it does that, that’s all I’m looking for.

- David Weiss

Please note: When you buy products through links on this page, we may earn an affiliate commission.

[…] “A great record does one basic thing: It creates a feeling.” Read the full feature here. Ken Andrews is managed by GPS Management | Record producer management, mixer management, audio […]