Photos, Revelations and “Rock and Roll Legends”: Studio History Lost and Found

What’s better than having a front row seat to music history?

Michael Friedman knows: Being fully embedded in the action is the next level. As part of the legendary manager Albert Grossman’s ABGM firm in the late 1960’s and early ‘70’s, Friedman was in the thick of things with many of the most groundbreaking artists of rock, pop and folk. It’s a who’s who that includes Bob Dylan, The Band, Janis Joplin, Paul Butterfield, Ritchie Havens, Peter Paul and Mary, Todd Rundgren, Kris Kristofferson, and Gordon Lightfoot.

His job enabled him to get up close and personal with these iconic stars, but it was his serious hobby as a photographer that puts a twist on Friedman’s story. Working day to day with them didn’t just give him access, but established a comfort level that came right through his camera lens.

Between 1969 and 1973, Friedman took over 1,000 photos from his unique vantage point – onstage, backstage and in the studio. But these historically significant shots were almost never seen again: Before he even printed most of the images, he packed the negatives away, and then lost track of them, eventually considering them lost.

But in 2017, after 45 years, the missing negatives were discovered in Friedman’s Connecticut attic. And now this treasure trove belongs to the world. The California Heritage Museum has selected a collection of more than 60 images for the exhibition ROCK & ROLL LEGENDS, THE LOST NEGATIVES OF MICHAEL FRIEDMAN, opening on April 14, 2018 and continuing through July 15, 2018. (Editors Note: The exhibit has returned for a showing September 26-October 31, 2018 at Canvas Malibu in Malibu, CA. Besides being on exhibit, the entire collection is available for purchase — contact co-curator Donna Vita for more information at donna@michaelfriedmanphotography.com).

As you’ll see in this interview with Friedman, sometimes the best perspective on studio life comes from someone besides an engineer or artist. In this case, Friedman’s status as a trusted friend and skilled observer gave him unique insights on the audio aspect of his clients’ iconic recording careers.

In this interview, Friedman gives SonicScoop readers a rare window on a groundbreaking time in music production. From artists’ favorite facilities, to the arcane studio rules that may have sown the seeds of today’s independent recording scene, read on for a slew of optically-actuated surprises.

The story behind these photographs could be called “Lost and Found.” How did this collection vanish, and then come back into the light?

Well, these photographs were mostly done between 1969 and 1973, when I was in the music business. I was also very interested in photography because my best friend was a very successful fashion photographer, and he was a mentor to me. I loved working in the darkroom and I loved his style of photography.

It became a serious hobby so sometimes I would just have my camera with me at gigs. I was pretty much a fly on the wall in the sense that nobody was posing for me, I was just there as part of the team. It was a relaxed environment for me to take pictures.

Michael Friedman was unexpectedly reunited with a treasure trove of his historical rock photographs.

Because I wasn’t a professional photographer, I always had a good seat at the table. I always had an all-access pass and access is half the battle with this type of photography. So I’d be in the dressing room and in the backstage area and sometimes actually on stage. Like the one of Mick Jagger that’s being used as the centerpiece of the show that’s coming up at the museum I was actually on stage just feet away from him at Madison Square Garden when I took that picture.

After I took all these pictures I had the film developed. I only made prints of a few of them, mostly to give to my kids someday. I put the negatives away and I never really thought much about it. Then at some point I went looking for them and but couldn’t find them. That was 50 years ago.

How did they resurface five decades later?

Last February my wife was straightening up things in our attic and came across a box of old music business papers and there was an envelope in there. And lo and behold it was these negatives that had gone missing half a century ago! I never thought I would find them again.

So we proceeded to scan them and made digital contact sheets. We started looking at them and thought, “These are pretty good!” They were better than I had ever imagined. One thing led to another and the next thing you know, the California Heritage Museum decided to do a three-month exhibit of the images. It’s just kind of serendipity, one thing after another, and I’m shocked that all this is happening.

Growing with Albert Grossman

You were working with Albert Grossman at the time, right? Were you a music manager yourself or you were his assistant?

I was Todd Rundgren’s manager at that time and Albert’s assistant. I had started out working with a guy named John Kurland in the publicity PR end of the music business and John and I signed the band Nazz from Philadelphia, Todd Rundgren’s band. John died unexpectedly so that was the end of the PR business. Shortly thereafter a friend introduced me to Albert Grossman who was looking for somebody to work with him and it was perfect timing for me. I met with him and we hit it off.

Next thing I knew, I was working in New York in the Grossman office and I brought Todd with me. The Nazz had broken up at that point. The plan was to manage Todd as a solo artist.

I was working with all of the artists in the Grossman stable. I think I was 26 when I joined him. Albert had the best music management firm in the business in those days. We had The Band, Janis Joplin, Bob Dylan, Richie Havens, Ian and Sylvia, Gordon Lightfoot, I mean it went on and on. Odetta, The Electric Flag, Paul Butterfield Blues Band, James Cotton. It was a huge roster and all of them were active, so it was a lot of work but it was also a lot of fun. I found myself in a real sweet spot in terms of the artists that I was working with and doing what I really wanted to do.

That’s where it started, I think it was in 1968 that I joined Albert. At that time he was spending a lot of time in Bearsville (Woodstock) building his empire and I was in New York City. Eventually I moved up to Woodstock and worked there when they started building the Bearsville studio and The Bear restaurant etc…

What were your personal impressions of Albert Grossman? He stands as a somewhat controversial figure in music history.

My personal relationship with him was great, Albert was always very nice to me and he and I got along great. He was a bit of a father figure to me, even though he wasn’t old enough to be my father. But he had this kind of paternal presence and I think many of the artists that we represented felt that way too.

He was a unique character, he was brilliant but he could be pretty mean, pretty tough. But it was interesting because he was really able to relate to the artists that he was managing, and he was breaking new ground all the time. In a way, he was writing the rules in an industry that was young at the time and somewhat unstructured.

Like, he would negotiate a contract and get $100,000 more than anybody ever dreamt of getting just because it was him, or because he could. He set a lot of the rules on their ear that existed at the time — but there weren’t that many rules!

He tried to have a somewhat self-contained operation among his producers and artists. He’d use the same producers and session guys and band members, and people would move around from one group to another. They were all sort of in his overall sphere of influence, so to speak.

But he could also be very mercurial. People were afraid of him, and a lot of people didn’t like him because he was tough; he spoke his mind and he wasn’t always politically correct. But we remained friends throughout. I ended up deciding to leave Woodstock after living there for a couple years and I moved back to Connecticut where I went to work with Bert Block managing Kris Kristofferson and Rita Coolidge.

A Very Different Studio Scene

At that time, how would you characterize the interactions and the level of thought that went into your dealings with the various recording studios and producers that your artists worked with?

As far as the Grossman office is concerned, I had had some experience in studios before I joined Albert. I had done a number of smaller projects in L.A. and New York. In fact, I produced the first Nazz single, which was [the original 1968 version of] “Hello It’s Me” and “I Saw the Light,” which I think was the B-Side. In that case I was kind of the producer by default because the actual producer didn’t know anything about producing a rock and roll record, so it sort of fell to me. And I think that may have been the only time Todd did not produce something that he played on.

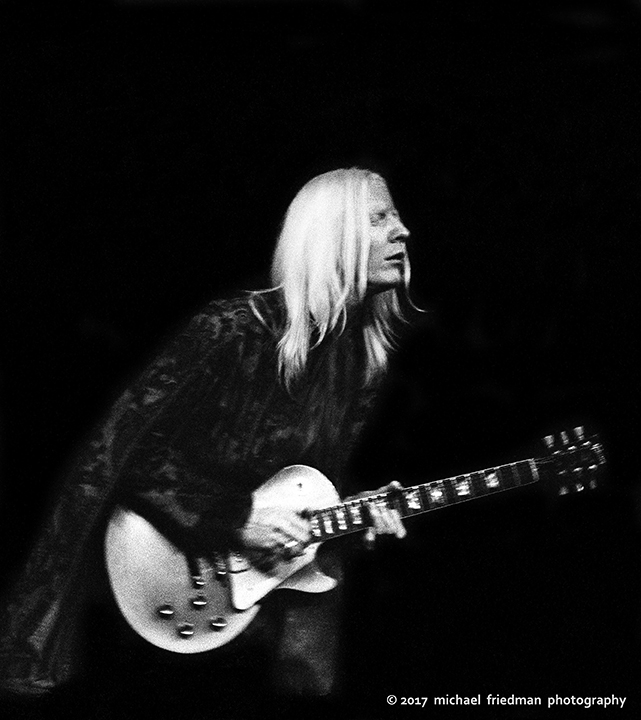

A closeup on Todd Rundgren recording the “Runt” album in 1969, guitarist Tony Sales is in the background. — © 2017 Michael Friedman

I’ve had some interesting studio experiences all the way from back when I was a kid. I think my first experience in a studio was when I had a high school band. We saved up $60 and went into New York and were able to afford two hours of studio time.

Those were the days when the engineers were all a bunch of old union guys, and you weren’t allowed to touch the board — even the producers couldn’t touch the board in those days. I remember we couldn’t even go into the control room to hear a playback; we had to listen to the playback from the studio. And at the end of it, they’d give you an acetate and that was what you got for $60.

That is different from today.

But the most interesting experience was my second time in the studio. I remember it was a group of us from Connecticut and we decided we were going to record some songs, so we drove out to New Jersey, somewhere just over the George Washington Bridge as I recall. We loaded up the station wagon and we went to this guy’s house. He had a recording studio in his garage. He was the nicest guy and his wife was lovely; she brought us milk and cookies. It turned out that the guy who owned the house and the garage and the studio was Les Paul! This was probably 1959.

Of course we didn’t even know at that time what that really meant. I guess he was just doing it to make money, and that’s where he was recording himself. I think the lady that gave us milk and cookies must’ve been Mary Ford because that was his wife. When you talk about analog, he was a genius. His records with Mary Ford were just amazing. He invented so much of the technology from that time. That was really a fun and memorable experience.

Later on when I was managing Nazz, we went to London to record an album for Screen Gems Music. In those days if you went to England, the unions were so strong with the studios that you had to get an English group to come to the States in exchange for you going over there. Have you ever heard of that?

You’re kidding. No, I have not heard about that.

Well we didn’t do that, we just went over there. We were in the studio and one day a guy walks in, flashes a badge, and they kicked us out of the country! I have a picture of me in a limousine on my way to the airport after having been thrown out of the country.

That was a big thing in those days. The unions controlled the studios. They controlled everything, really, and If you touched a knob on the board, the engineer would get up and walk out of the room and that was the end of the session. You couldn’t go near the board, you couldn’t touch it.

I think that’s why so many of the little independent studios started popping up. Because they were non-union studio owners and engineers, many producers wanted to use them.

How did that impact the management side of things?

As far as the guys in Grossman’s office, Albert’s concept was to try to keep everything in the family, and in hindsight I think it was because he got a piece of everything.

So he was getting a piece of the producer if it was one of his producers; the studio time, if it was his studio; the management, the publishing, the songwriting, everything.

But his idea was to try and put everybody together. With Peter, Paul, and Mary, the story I had heard when I got there was that Albert helped put that together as a vehicle to try and get hit records with Bob Dylan’s songs, because Bob wasn’t getting hits singing them himself. It was a way of getting into the folk market that was more commercial, and getting airtime and record sales.

With the recording studio up in Woodstock, (Bearsville), it took forever to get that thing built and to get it sounding right. It was years, actually. I remember when they were breaking ground for it and then two years later they were still trying to get a sound out of there that they could live with. [Producer for The Band] John Simon and some engineers spent a great deal of time building it and tuning it. It was intended originally to have a place for The Band to record but also for Albert’s other artists as well.

Eventually it became a commercial studio where they would just rented it out to whoever wanted to come up there and record, which a lot of guys did. That got all tied in with his own record label and so on and so forth. It was all very much part of the same concept, many branches of the same tree.

Were these studio photos of Todd Rundgren taken at Bearsville?

No. That was done out in California. I forget which studio it was, it would probably be on the liner notes, but it was the Runt album and Todd played most of the instruments. The other guys in the band were Soupy Sales’ two sons, Hunt Sales and Tony Sales.

Did you see the picture of Todd playing the saxophone? I don’t remember him ever playing the saxophone or knowing anything about it but he wanted to do a little overdub or something and he brought in a saxophone. He just played it, he didn’t really know how to play the saxophone but he did it. He figured it out.

That was the thing about Todd, he was able to do whatever he wanted because he was so talented and very bright. He could also be incredibly difficult to work with, and I didn’t always enjoy working with him, but he was brilliant. In some ways, I think that even though he’s been very successful, he could’ve been even more so if he were easier to work with.

Well, you hear that a lot about super-talented people, and you worked with a lot of them. Why do you think that so often has to go hand in hand?

It’s interesting that you ask that, because I’ve thought a lot about it. I think it’s part of a narcissistic personality. I’ve noticed that these types of people tend not to be able to share very well, because it’s always all about them and doing it their way. For better or for worse, Todd was the quintessential example of a guy who would not take advice from anybody. With guys like that you have to sort of be on their trip the whole time. It’s fascinating.

Keep in mind I’m talking about when he was 22 years old, so maybe Todd’s grown into this not-so-difficult guy. I haven’t seen him in many, years.

Recording Insights from Early On

You got to have this front row seat to some of these amazing artists working in the studio while they were recording songs that would go on to be huge hits or parts of hit albums. What would you say is the common thread you saw among these artists, regarding what they were able to accomplish in the studio when they were recording?

I think it was very varied. There were certain people that came in really well prepared, and others that tried to figure it out in studio.

In the beginning when you went into the studio you had rehearsed all your songs, everything was ready to go, and there wasn’t a lot of overdubbing. Initially it was two tracks and then four tracks. When I first started, there wasn’t even Dolby, it was basically a live experience. When four-track came in, you could overdub some harmony vocals, you could overdub a guitar solo, but that was about it early on. When they started adding tracks producers started adding layers.

But, essentially, you went in there ready. If you were a group, you went in prepared to make a record and you would sing and play at the same time and then you would listen to it. And if you felt like you wanted to add a few tracks, you did. But then, somewhere along the line it got to be 32 tracks instead of four tracks, and you could do so many other tricks of the trade.

I remember the last record I made for A&M when I had my own little production company. We recorded in Jerry Ragavoy’s studio, The Hit Factory. Jerry and I had gone way back and so I made a deal with him that we would use his studio from 10 o’clock at night every night that it wasn’t booked until 6:00 in the morning.

I had a group called Mayday that I had signed to A&M. It took a year in the studio to make this album. It was crazy. It was thousands of hours because we had unlimited time and at the end we had to pay Jerry whatever it was at a highly discounted rate, but A&M was paying for it. So every song would take three weeks or a month, and it was so inefficient.

What it ends up doing, or at least what I thought it ended up doing, was taking the soul and the spontaneity out of the performances. There were demos that these guys did that were better in some ways than the finished album because it was organic and it was live. Those tapes really had the energy and were the real deal. But if you start doing stuff like overdubbing the vocals 12 times etc., you end up with a more manufactured or canned product and for me that’s not what Rock and Roll is all about. And so that’s kind of how it was when I left the business, I don’t know what it’s like now with guys making records in their living room or in their bedroom.

That’s what I liked about Dylan, he would go into the studio and he’d even still be writing lyrics during the session. And if it wasn’t perfect, it was okay because he liked it. Bob Johnston was the kind of producer that would say, “Yeah, I agree with you. We don’t need to do this 100 times.” Whereas John Simon, on the other hand, spent a long time producing some of The Band albums. Personally I prefer the approach they took on the Big Pink album which was more live and organic, and John produced that one too. But don’t get me wrong, they were all great albums and John is an amazing producer.

Do you recall having a recording studio that stood out to you as being one of your favorites that you knew you were going to be at in any capacity, either managerial or producer, or a studio that you know was a favorite among the artists that you worked with?

As I recall, a lot of guys liked to record at The Record Plant in New York and Sunset Sound in California. They were thought of as having a good sound. And that was the other thing: studios had their own sound, supposedly, and they were very guarded about protecting that.

I remember when I was still doing publicity before I went to work with Albert, on a publicity tour with The Bee Gees. We were in Detroit and Barry Gibb wanted to see “Hitsville” the Motown complex, which consisted of five houses on a residential street. Berry Gordy had turned them into different units, one house was for choreography, one was business affairs, one was a studio, one was for advertising and marketing, etc… All the Motown artists were just hanging around and talking, and kind of living there. They all lived in Detroit but they were hanging out on this street where the Motown houses were. It was like a big family.

I remember walking into the studio and I had a camera around my neck and the receptionist said, “You can’t take that into the studio.” I said, “Well, why not?” She didn’t say, but I found out later that they thought that the room itself had sound characteristics that they didn’t even understand, and they didn’t want anybody else to be able to reproduce it. So you weren’t allowed to take photographs in the studio. When you hear all those Motown records, they do have a distinctive sound, the ones that were made there. So there is probably something to that.

A few of the popular studios in New York were the Hit Factory, the Record Plant, Electric Lady which was Jimi Hendrix’s studio.

Did you record in Nashville as well?

Yes, but In Nashville it pure country and it was just was a different feeling and sound than you got in New York. There was a guy called “Cowboy Jack” [Jack Clement] who was a famous producer and engineer in the early days at Sun Records in Memphis with Sam Philips. He worked with all the great Rockabilly artists like Jerry Lee Lewis, Carl Perkins and others.

He moved to Nashville and opened his own studio and he was such a character. I remember he had this thing where we finished recording one night and he said, “Let’s all go to my house and have a drink.” So we went to his house and his idea of fun after a long day in the studio was putting you in this office chair that turns, and after giving you about five shots of Jack Daniels, he’d start spinning the chair really fast. That was having fun… Nashville style!

The next night he didn’t tell us where we were going but he took us to this brick building downtown. We went in the back door, up some stairs and he sat us down in a row of folding chairs. All we could see was a giant velvet curtain in front of us. We didn’t know what was going on until a band started to play and the curtain was raised. In front of us was an audience of about 500 people. We were actually on stage at The Grand Ol’ Opry at the old Ryman auditorium! It was a mind-blowing experience. Jack had that kind of pull in Nashville.

Up Close and Very Personal

What would you say elevated the experience for you, of not just being on the scene but being able to take photographs and visually record the moment? Why was taking pictures something that you felt compelled to do?

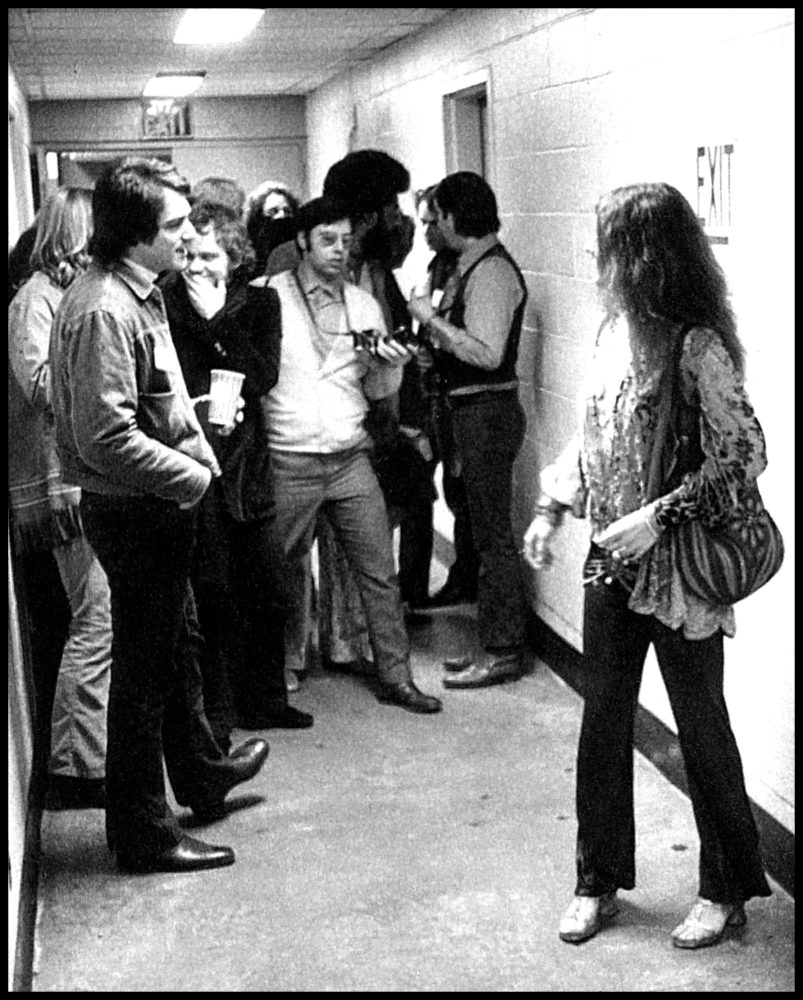

Michael Friedman (far left) and Michael Pollard (in black shirt) backstage at Madison Square Garden with Janis Joplin in 1969.

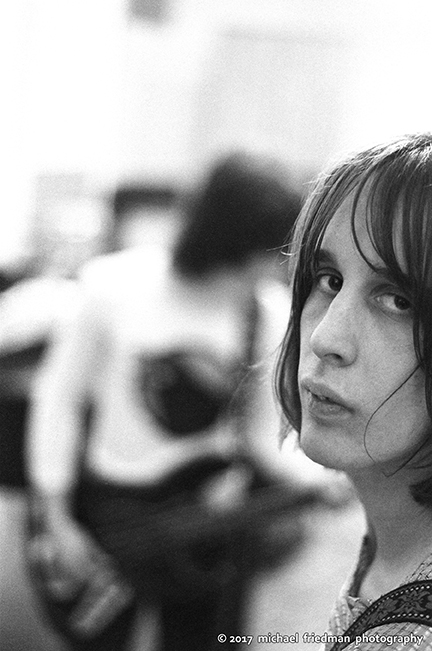

I’d say it was the individuals that I ended up taking pictures of. The thing about my pictures was that I didn’t take one unless I felt like whoever’s picture I was taking would be cool with it.

And most of the time it was an artist that I felt most comfortable with. Like, I have probably five times as many pictures of Levon [Helm]as I do of Robbie or Garth [Hudson], because Garth was quiet and sort of guarded and not a public kind of person — I would’ve felt like it would be somewhat invasive to have a camera shooting at him.

But some of the other guys, and Janis, were used to cameras being around them all the time, so they were easy to photograph. Janis was all about what she was doing at that particular moment so she wasn’t paying attention to me.

Also, I gravitated towards the people that I felt strongly about on a personal level, like Kris Kristoferson who was one of my favorite people I ever worked with and I loved hanging out with him. I liked taking pictures of him wherever we were. Rita too because she was beautiful and talented and so nice. And then there’s a few pictures from the Trans Canada Festival Express that I liked. Backstage shots just catching a moment of something happening, more recording the moment than trying to have control over it. There’s a thing called reportage photography, which was what a lot of the great photographers were into whereby they were able to capture a great moment happening. They are the ones I admired most when I was into photography.

How is your show at the California Heritage Museum pulling all of this together, in a new way for you?

I was never aware of it, but when I looked at all these pictures at the end of the printing process and saw them all together, I realized that there was kind of a theme, something that held them together as a group. Many people have commented that they seem more personal than other photos of musicians they had seen. Whatever it is, I hope people will enjoy them.

— David Weiss

ROCK & ROLL LEGENDS, THE LOST NEGATIVES OF MICHAEL FRIEDMAN, opens on April 14, 2018 at the California Heritage Museum. The entire collection is available for purchase and can be pre-ordered several different sizes (framed and unframed). Donna Vita (Co-Curator of the Exhibit) is the point of contact for all sales and her direct email is donna@michaelfriedmanphotography.com. Visit Michael Friedman’s Website for more information.

Editors Note, 9/25/18: The exhibit has returned for a showing September 26-October 31, 2018 at Canvas Malibu in Malibu, CA, located at 23410 Civic Center Way, Malibu, CA 90265. Phone: 310.317.9895

Please note: When you buy products through links on this page, we may earn an affiliate commission.