Real Producers and Engineers Know How to Use Amp EQ

Mark Marshall’s new course, Producing and Recording Electric Guitar is out now.

Guitarists, producers and engineers alike are often presented with a wide variety of amps to choose from, whether it’s on stage or in the studio, a collection of vintage tube amps or virtual ones.

Sometimes, you’ll encounter an amp that you’ve never used, and you will still need to figure out how to make the most of it.

This is made more difficult by the reality that each amp not only sounds different, but also operates in its own manner when it comes to things like gain staging and EQ.

That’s right: You can’t just dial up your Fender Deluxe settings on a Vox AC30 and expect them to translate. They simply won’t.

Fortunately, with a little understanding about how each of the major types of guitar amp will respond to your tonal tweaking, you can take a lot of the guesswork out of the equation and start finding your amps’ sweet spots much more quickly than if you just go about turning knobs in the (metaphorical) dark.

Four Rooms

Before we get started, its important to recognize that each room you record or perform in will sound different. Your bass and treble response can be completely different depending on the room you are playing in.

Sure, there are some sessions when I fire up my amp and I don’t have to touch a thing. This is a result of either keeping the setting from the night before, or from playing knob roulette. (Meaning, wherever the knobs got bumped without me noticing.)

When you do have to consciously make changes to the EQ on an amp, it’s really helpful to understand the way in which each amp operates. This is especially true in instances where there isn’t a lot of time to experiment.

Fender, Vox, and Marshall amps all act differently when it comes to EQ. They may all have knobs named “treble” and “bass”, but that doesn’t mean they influence the same frequencies, or in quite the same way. I have seen many guitarist scratch their heads when playing a Vox or Marshall for the first time. (Including this guitarist.)

The Fender EQ

In America, Fender Amps tend to be among the most common. If you’re dealing with house gear at a studio or at a venue, it’s likely you’ll get a Fender unless you specify otherwise.

Even though many American guitarists are accustomed to running into these, most still don’t understand the way the EQ operates on Fender amps.

Most classic Fender amps have 2 or 3 EQ knobs: Bass, Midrange, and Treble that go from 0 to 10. Seems simple enough. Most guitarists assume these amps work on the idea that “5” is a middle choice, and turning them up beyond this adds more of each frequency.

Makes sense. But it’s wrong. In reality, these are cut knobs. Leo Fender actually designed the Fender circuit to be flat with all EQ knobs on 10!

The tone controls on traditional Blackface Fender amps are passive. In fact, most EQ knobs on the best tube guitar amps are passive. The major exception is the graphic EQ on some Mesa Boogie amps. They are active which means you can cut OR boost frequencies.

Have you ever seen a guitarist start with all the EQ knobs turned up and take them back slowly? Now you know why. I know it seems weird, but I encourage you to try it! It brings out other qualities in the amp you might not know exist. Most notably, the midrange on amps that don’t have a midrange knob.

Blackface Amps

Some blackface Fender amps only have two EQ knobs: Bass and treble. You’ll find this on such models as the Princeton and The Deluxe.

This doesn’t mean the amps don’t have midrange. They do. However, by nature of their design, blackface amps have a more mid-scooped tone than some of their older siblings like the Brownface or Tweed.

One way to get more mids out of a Blackface-era Fender is to pull the treble and bass back. If you start with bass and treble on 10 and slowly lower each one, you’ll not only hear less bass and treble, but more mids.

This also works in reverse if you’re looking for less mids: Crank the bass and treble up.

You will notice that as the amp EQ is turned up, you get more volume from the amp. So keeping the EQ knobs up can coax more gain from your amp. As you pull the EQ knobs back, the volume is reduced, thus cutting gain.

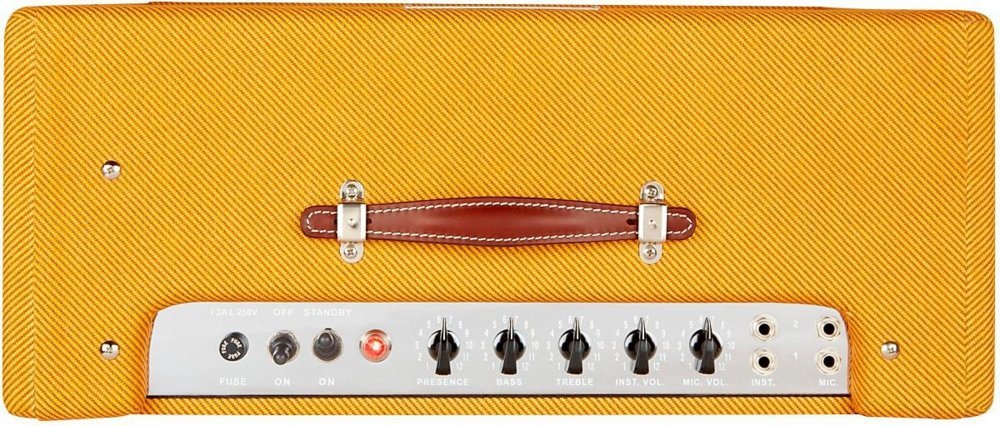

Tweed Amps

The EQs on Tweed-style Fender amps can be as simple as the titling tone control on this little Champ, or can add in extra controls like “presence”.

There are two types of Fender tweed amps in my mind: Those with one simple tone control and those with presence, bass, treble and sometimes mid control.

The revered Tweed Deluxe is a unique amp in many ways. First off, the tone knob acts like a cut OR boost. In the middle, it’s flat. Turning it up higher adds more treble. Turning backwards cuts treble.

But it’s not just the tone knob that alters the EQ on Tweed Deluxes.

Riddle Me This

How many guitarists does it take to figure out how the instrument and mic inputs work on a Tweed Deluxe? (After this article, I hope only one.)

The volume knob for the instrument channel and mic channel are interactive. If you plug into the instrument channel on the Tweed Deluxe and turn the volume up midway, you’ll hear a healthy amount of midrange. But, if you start turning up the mic volume knob, you’ll hear the tone changing. With the mic knob midway, you’ll start to hear the midrange get scooped.

(Tip: You should also experiment with plugging into the mic channel on its own. It distorts quicker than the instrument channel.)

Under The Bridge Downtown

On older Fender Tweed or Marshall Amps, you can do something called “jumping channels”.

This means you run one channel into another using a patch cable. Typically on these amps, there is a “bright” channel and a “normal” channel. You can not only get more gain by running the channels into each other, but you can further tweak the EQ.

Running a really bright channel into the normal channel can soften the shrillness, especially as you start pushing the amp harder. The opposite works as well, and you may want to try running the normal channel into the bright one to brighten up a guitar tone.

Big Brother

Larger Tweed Fenders often add on a presence control and allow for “channel jumping”. Click to enlarge.

Bigger tweed amps like the Pro, Super, and Bandmaster have more tone shaping options. The most notable difference is the inclusion of the presence knob.

One thing to know is the presence control is not in the same part of the circuit as the treble, mids, and bass controls. You may be asking, “Why does this matter?”

Unlike the Treble and Bass knobs that cut frequencies on Tweed amps, the Presence knob can actually boost some of the frequency band. By playing with the Presence knob you can actually make the amp distort easier on higher notes. This has to do with the placement of the Presence knob in the circuit which is in the power amp stage.

The Presence knob is an interactive knob. It behaves differently depending on the amp volume. It can even influence the behavior of the speaker and it’s ability to handle high frequencies, especially at loud volumes.

When you are going for a clean sound, the presence knob will influence the treble and upper mids. But if the amp is really cooking from power tube saturation (volume high), it causes the high notes on the guitar to react unpredictably.

To me, the presence knob is the “danger” knob. You won’t always know what’s it’s going to do unless you play at the same volume all the time.

Those of us that like tweeds live on the edge a little. We’re the ones that got detention, ignored curfews, and probably made a few teachers despise their jobs.

Vox

One of the most confusing things about Vox amps is the ever-elusive “tone cut” knob. These don’t appear on every Vox amp, but you’ll find them on the classic AC30 Top Boost amps.

Before we get to the behavior of that pesky tone cut knob, let’s talk basic Vox EQ. When you plug into the “top boost” channel of a Vox, you’ll have control over treble and bass.

These controls aren’t so different from Fender Amps: They are passive and cut frequencies rather then boosting them. But, unlike Fender Brownface and Blackface amps, the tone stack comes after a stage of gain. (That’s something we’ll see again when we talk about Marshalls.)

These amps react a little differently than Fenders. Turning the treble knob on a Vox back will cut treble and allow more upper mids through. Turning the bass knob back will cut bass and allow more lower mids through.

Just like with Fenders, with the treble and bass all the way up, a Vox amp will be in it’s most mid- scooped stage.

Remember, as you cut frequencies you lose volume and gain. When cutting frequencies to get more midrange, one has to turn the volume up to compensate if we desire the same volume. It’s also worth noting that when cutting frequencies, an amp will not break up as quickly due to the volume loss of the frequency cutting.

Yeah Yeah Yeah, Get to the Good Part

As mentioned earlier, some Vox amps have more than a bass and treble knob. They have a tone cut knob.

The tone cut knob confuses a lot of people. Why wouldn’t it? It’s not on Marshall amps. It’s not on Fender amps. This is a Vox thing.

Basically, the tone cut knob phases out (doesn’t cut) high frequencies as you turn the knob up. Yes, the opposite direction of how all the other dials work. All the way down, there is no phasing out of high frequencies, so you get the brightest tone. Turn it up and you cut the high frequencies, darkening the tone.

The tone cut knob is interacting with the power section of the amp. It’s in a completely different location in the circuit than the treble and bass controls.

Why another treble adjustment? As you start pushing a Vox AC30 they could have quite a bit of bite. But you may not want to turn down the treble because you have the treble and bass knobs dialed in to your midrange preference. Using the tone cut can solve some of the harsh highs that may be the result of cranked volume and EQ settings.

Marshall

Marshall amps, like Fender and Vox have passive EQ controls. On the most common Marshall’s, you’ll have presence, treble, midrange and bass. These are the same options you would find on a Tweed Fender Bassman, which the early Marshall’s were derived from.

In fact, they operate a lot in the same fashion. You can even jump channels for further tone and gain control. The presence knob also exists in a different part of the circuit than the treble, mid, and bass. Volume interacts with the presence knob just like on tweeds.

The Marshall circuit has a gain stage prior to the tone section.This is unlike a later Fender Brown or Blackface amps where the tone stage comes first and the gain stage follows.

An amplifier with a gain stage placed first followed by a tone stage does not have as dramatic an effect on how the controls (Treble, Mid and Bass) operate, compared to an amp design where the tone stage comes first and gain stage afterwards (like higher powered Fender Brown and Blackface designs).

Marshall amps are very midrange rich, considerably more so than Fender and Vox. Even though all three of these amp makers use passive EQ, the frequencies they cut and the gain in the circuit is different. Marshall amps have the most gain and the least midrange scooping of all these amps.

Two Scoops

You might be wondering, “What’s the deal with all this mid range scooping?” That is, if you’re a good student. You are, aren’t you? Great! I’ll be expecting a gift on Teachers’ Day then. Preferably something in a sunburst, if you get my drift.

Most guitar amplifiers cut midrange to some degree. This is because guitar pickups are very high in midrange by nature, and so amp circuits generally cut midrange by default to try and make the frequency response flat.

Of course, it’s never perfectly flat. And the selection of what midrange frequency gets cut is different on Fender, Vox and Marshall amps. There is a frequency DNA for each amp. It’s like being born with brown hair. You could dye your hair blonde, but you’ll still have brown roots. (Although, my grandma wasn’t convinced of this. She thought she had everyone fooled. I wasn’t gonna be the one to tell her!)

Trying to make a Fender Amp sound like a Marshall is very similar. You can give the illusion that it is similar. But you always know when someone is a natural blonde.

The Awakening

Ideally on a session or gig you want to feel in control of your tone. Both of these situations tend to be high pressure. A distraction such as struggling with the operation of an amp can add stress.

I mentioned some fo the most common amps in this article. Thee are many variations on these designs, and some modern takes that are entirely different. I encourage you to do a little home work before a session or gig when you might be using a new amp.

Research a few key questions: Does the amp have passive EQ? Does the tone stack come before or after a stage of gain? Is it a negative feedback amp? How many EQ knobs does the amp have?

These basic inquiries will tell you a lot about the amp you’ll be dealing with. Also, if possible, get the the session or soundcheck a little early to experiment and don’t forget, volume influences the tone. An amp often sounds a little different at stage volume than at bedroom volume.

Well, I hope these tips will help you keep out of TREBLE on your next gig or session and allow you to really AMP up your performance. Ba-zing!

Mark Marshall is a producer, songwriter, session musician and instructor based in NYC. His new course, Producing and Recording Electric Guitar is out now.

A special thanks to Greg Germino of germinoamplification.com for his insight into amp circuitry.

Please note: When you buy products through links on this page, we may earn an affiliate commission.