A Great Mix is an Expressive Mix

This is Part 1 of a new series on mixing by Wessel Oltheten, author of the book Mixing with Impact.

Performers don’t just speak with their sound. They express themselves with their whole body. Read on to learn how to recreate that kind of impact in audio-only recordings.

“Expression” is the language used by all good musical performers, whether they are musicians in a band or programmers of beats.

As a producer or an engineer, you could see your job description as simply the capturing of that language: You record a performance, mix it to enhance definition between parts, and be done with it. However, if you do it well, the job is somewhat more involved than that.

By capturing a performance and playing it back to an audience, you’re translating the artist’s expression into a new context where the artist might not have imagined it when they made the performance. A live concert can end up in someone’s ear buds on a train ride, for instance. A studio demo can later be used in a feature film, and so on. The expression that worked in one context won’t automatically work in the next.

The Size of Your Expression

It’s important to recognize how powerful expression can be. I once heard an actor recite a poem that featured ten repetitions of the same sentence. When the actor came back to that line again and again, it didn’t feel repetitive. The sentence’s meaning seemed to shift throughout the poem. When I later read that poem on paper, I realized just how much the actor’s performance had contributed to its depth of meaning.

This is what expressive performance can do: It determines the shape the information comes wrapped in, and it tells you something meaningful about how to interpret that information. Talented performers can “supercharge” even unremarkable information to the point of it becoming an emotional experience. This goes for words in a sentence, and also for melodies and chords. But not every expressive choice will work in every context without your help.

A good analogy is stage acting versus acting in a television drama. On a stage, actors need to project their message over a much greater distance, to reach audience members far from the action. This requires over-pronounced articulation and big gestures, which work great in a theater, but seem overly dramatic when the play is recorded up close and broadcasted on television.

It can also work the other way around: If a band want to create the sensation of playing in front of a stadium crowd on their studio album, they have to “scale up” their expression from what might seem natural in the studio. They have to perform as if they actually are playing for the masses—instead of being tucked away in a vocal booth. Only then (and with some judiciously added reverb and delay) will their performance sound credible.

As a producer, you have to anticipate on how such translations will pan out. In order to do this, you need a clear idea of what you’re going for. I start by envisioning the size the expression needs to have in the context I’m going for: How close will the audience be to the performer? Are we being invited in to visit an artist’s inner world, or are we being blasted with a wall of sound from a distance?

Once you’ve determined the right perspective for the production, you can think of ways to help performers express themselves in that context. It starts by making them consciously aware of what the goal is, and how a new context may require a different approach than what they are used to.

It helps to have a vivid imagination (which most artists are blessed to have), but you can help them a great deal by providing headphone mixes that match the sonic goal while you are recording. If a singer barely hears himself and feels a lot of power from the surrounding band, he’s more likely to sing big. If he is loud and dry sounding, he’ll likely opt for a smaller and more intimate expression.

Verbal communication about abstract concepts is inherently limited, so you may need to coach performers throughout the session. No matter how much you’ve discussed it beforehand, sometimes a drummer needs to experience how playing softer will get him a bigger sound. Even when a producer, a dedicated vocal coach or a conductor diligently take care of all this coaching—and even when a musician is theoretically aware of how her performance will translate to a recording—some real evaluation and feedback about the recorded performance is usually required.

Does the performance you captured work in context of the mix? Does it sound as good on playback as it felt during performing? Or, does it sound right on playback even when it didn’t feel right during the performance?

Will the captured expression survive being in a mix with more sounds to be added? Or do the dense surroundings of the vocal require it to be very compressed, flattening the expression too much in the end? In the latter case, it may be better to go for a more over-the-top, theatrical kind of expression, which will survive huge amounts of compression and still sound exciting, even if it seems “too big” in the studio.

In order to make these judgment calls, you need to be mixing during the recording process. You can’t just save it for later. Of course there will be a final balancing stage, but ideas need to be tested in context while they are still up for debate.

If you want to help artists translate their ideas, you have to be fluent in the ways artists can express themselves. This goes beyond music theory (the language system) and involves every nuance in the creative application of that system. Phrasing, intonation and any other way of attaching meaning to a sound are important.

After you understand what makes an artist’s unique sense of expression great, comes the challenge of translating that greatness to the production at hand. You want to make sure that it can reach a listener who wasn’t present during recording. This isn’t as simple as merely making a good capture.

Almost by definition, something is lost when you record a performance. Part of the power of a live performance is that it feels like it could still take unexpected turns, and is only present at that exact moment in time. A performer doesn’t just speak with his or her sound either. They express themselves with their whole body. Their entire demeanor is part of their expression.

These factors bring a sense of excitement to anyone present, but part of that excitement is lost in a recording when the physical and visual connection to the artist is gone along with the exhilarating feeling of witnessing a one-of-a-kind moment in time. These are some of the reasons you need to go to extra lengths to create excitement in a recording. Often those methods will involve bringing the artist’s expression closer to the surface of the recording, by selectively enhancing aspects of their performance.

As soon as you realize that electronic effects can be used for expressive purposes, it becomes tempting to drape a production in lots of sonic “character”, thinking this will automatically lead to an interesting result. But a random approach to processing usually doesn’t work.

Just like you can’t emphasize random vowels in a conversation and still expect your meaning to be clearly understood, music follows its own patterns of language, and in order for you to emphasize elements of a performance in a meaningful way, you need to get into the head of the writer and performers. What are they trying to say? How is their language structured? How can you help to make those structures more clear and powerful?

Phrasing and Memory

Expression can be seen partly as a way of ordering, grouping and prioritizing information by employing emphasis and pause. Emphasis can be created by so many mechanisms besides level. A performer can deviate from the expected timing or pitch to make a note stand out, or by making it brighter or darker than surrounding notes. Musicians use emphasis and pause to create musical sentences—chunks of information that belong together.

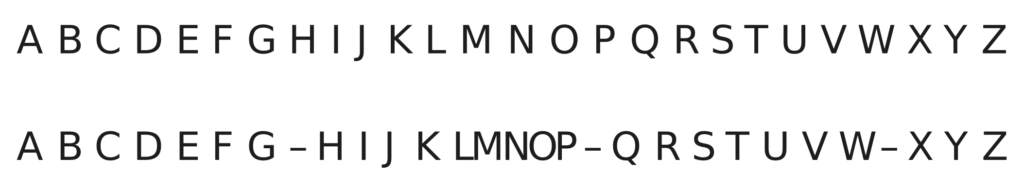

There’s a good reason for this. The amount of continuous information a human being can process is limited. You have to split large amounts of information up into smaller segments to be able to store them in memory. Do you remember learning the alphabet as a child? Many children do so by song: the 26 letters are segmented into a few of musical sentences, each a handful of letters long. Each of these sentences and phrases can be remembered as a unit, while the entire alphabet can’t be.

I find it very helpful to look for such ‘information chunks’ in music: Which notes belong together? Which elements seem to stick in your memory easily, and where do you breathe when humming them? Which are hard to remember? Where do the performers place emphasis, and do you hear that emphasis clearly enough for it to be meaningful? Where does a sentence lead, and where does it end?

The alphabet is much easier to learn when you subdivide it in patterns small enough to be stored in memory. Remember the alphabet song?

Usually, the musicians are doing all the phrasing you need. That’s one benefit of working with people instead of sequencers: they interpret a composition and perform it so that it automatically makes sense. But while that may be enough for a two-track recording of a well-rehearsed orchestra, most multi-track productions need a little extra help.

The act of gradually layering parts makes it easy to lose sight of potential conflicts with other parts—especially with those yet to be recorded. Also, when learning new parts and recording them on the fly, musicians tend to focus on getting the notes right, and less so the subtle implications of the part’s phrasing.

Finally, the programming and editing of parts allows for awkward ‘whole-alphabet-like’ phrasing to be introduced if you don’t consciously think like a performer while making your edits.

Fader automation is the easiest way to solve some of these issues. You ride an instrument, emphasizing the starts of new musical sentences when required; accenting important parts and deemphasizing less important parts. You effectively do part of the performance after the fact, building on or exaggerating what’s already there.

How much of this you will need to do depends a lot on an instrument’s surroundings. For instance, I find that phrases that start off-beat often need more emphasis on the first note to make the intended phrasing clear, compared to the collective effort of instruments that do play on the beat.

Remember to Breathe

For some time, I regarded things like violin bow changes, accordion bellow changes and even the breathing of brass payers as unfortunate necessities. By punching in, I could record beautiful uninterrupted lines of music! But before long, I noticed that the results sounded more like a continuous stream of alphabet letters than memorable music.

Sure, it’s unfortunate to breathe in the middle of an epic melody, but any experienced player that has studied the music at hand will make sure to time such things so they don’t feel like interruptions. If anything, breathing and pausing can actually be very beneficial to a performance when done right, and most singers automatically handle this very well because of the obvious parallels with spoken language.

I’ve since started to view most instruments like “singers with a different sound”, that also need to breathe between sentences—even when they don’t physically need to do so. A synthesizer can potentially keep on playing uninterrupted lines forever. But when musicians and programmers approach playing such an instrument more like singing (or even like talking), they tend to come up with much more memorable and better-structured parts.

Phrasing that matches a listener’s natural flow of breathing can be very inviting. Phrasing that clashes with these expectations—or that doesn’t allow the melody room to breathe—can be almost uncomfortable. (Which can also be used as an intended effect, of course).

Comprehending an Alien Language

The complexity of the music also factors in to how much clarification is needed. If a synthesizer plays a continuous pattern of the same three notes over and over again, I don’t need a pause to process the part. But in jazz solos that contain huge numbers of notes and rhythms, a pause between phrases is absolutely necessary for recognition.

When done right, this feels to me like someone is speaking to me in a language I don’t understand in a literal way. I can comprehend the tone and mood however, and also attach my own meaning to what I’m hearing—which is a joyful experience.

When I can’t keep up with the phrasing, process what I’ve just heard, that joy is lost. This tipping point is personal and will change with experience and musical training. That said, it is possible to make very complex structures more accessible by phrasing them right, and without losing any of their sophistication in the process.

To help you find elements that can benefit from your enhancing their expression, it pays to listen in new ways. You can begin to recognize the “backbone” of a piece of music by zooming out and letting your ear wander. If you tune out from the little details, what bigger structures are you left with?

A complex melodic phrase consisting of 16th notes can perhaps also be perceived as a simple ascending line consisting of four important quarter notes. If you accent those notes, you’re clarifying the structure for the listener, who now knows that the other notes are meant as decoration and less as crucial melodic information. You can also play with how you structure the same material. There are nice examples to be found of the same three beat phrase being repeated on a four beat meter, shifting which parts are accented with every repetition.

For now, start listening for the expressive choices that the musicians you are working with make and determining which ones could use a bit of extra emphasis. In our next post on this topic, we’ll explore a variety of specific ways to help enhance the expression of any of the elements in your mixes.

Wessel Oltheten is a producer and engineer who lives and works in the Netherlands. He is the author of the new book Mixing with Impact.

For more great insights into both mixing and mastering, try our full-length courses with SonicScoop editor Justin Colletti, Mixing Breakthroughs and Mastering Demystified.

Please note: When you buy products through links on this page, we may earn an affiliate commission.