The 11 Most Common EQ Mistakes to Avoid

EQ is arguably the most powerful tool at your disposal when working with audio.

It’s also tremendously easy to get EQ wrong. Over the years, I’ve noticed 11 common EQ mistakes that keep cropping up and can stop a mix dead in its tracks.

In this guide you’ll learn what these 11 mistakes are and what you can do to avoid them.

Mistake #1: Only Using Parametric EQs

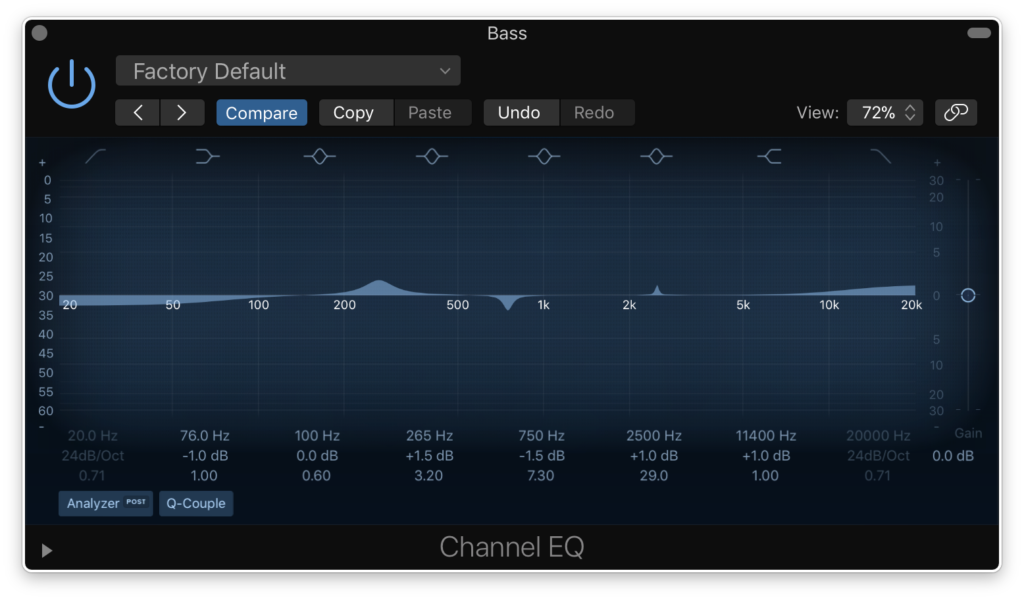

Don’t get me wrong, parametric EQs are great tools. Almost everyone has at least one good one at hand—the stock EQ that comes with your DAW is probably a pretty decent parametric EQ. They’re stellar for finding resonant frequencies and making surgical cuts and boosts.

Digital parametric EQs usually have a graphical display, which makes them exceptionally easy to use. But when it comes to making more drastic changes to a sound, you may find yourself trusting your eyes more than your ears.

Digital parametric EQs usually have a graphical display, which makes them exceptionally easy to use. But when it comes to making more drastic changes to a sound, you may find yourself trusting your eyes more than your ears.

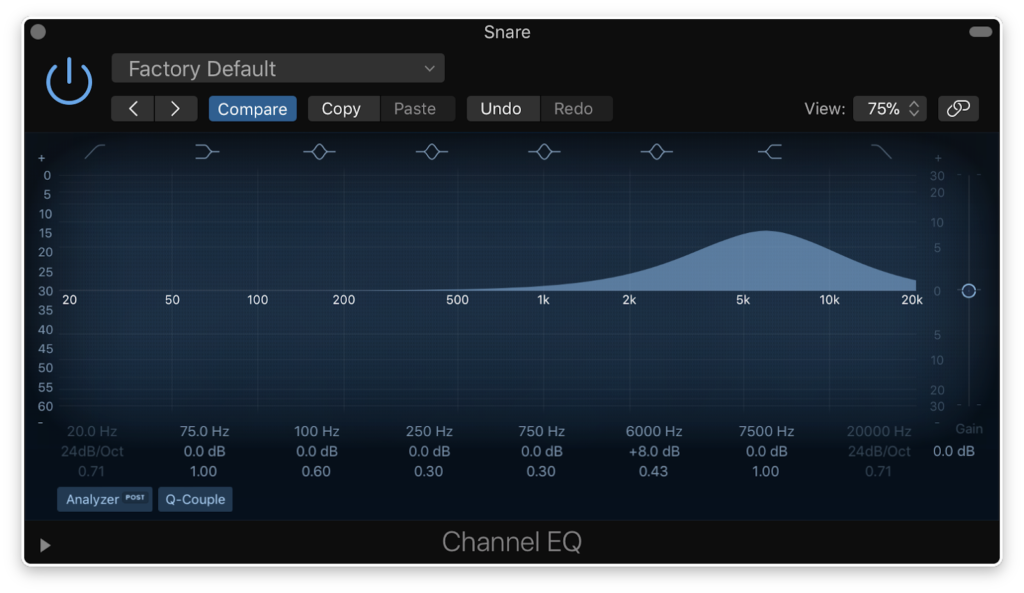

Say you want to really accentuate the “crack” of a snare. To do so, you may need to dramatically increase some high frequencies.

The problem is that it’s easy to see drastic boosts on a parametric EQ and immediately assume you’re going overboard. Even if it sounds good, the visual representation of a parametric EQ can make you feel like you’re overdoing it, so much so that you end up backing off the gain.

The problem is that it’s easy to see drastic boosts on a parametric EQ and immediately assume you’re going overboard. Even if it sounds good, the visual representation of a parametric EQ can make you feel like you’re overdoing it, so much so that you end up backing off the gain.

I took a break from parametric EQs for a while for this exact reason. I wanted an EQ that wouldn’t make me worry about how my decisions looked and kept me focused on how they sounded.

Analog modeling EQs push you to use your ears more than your eyes. Visually, they’re just a few dials with no graphic image of your boosts and cuts. You can add 8 dB of 6 kHz to your snare, guilt-free!

Taking a break from parametric EQs also helped me train my ears. I got a lot better at using my critical listening skills to make EQ decisions, and my mixes improved drastically.

If you don’t already have an analog modeling EQ, try out Slick EQ. It’s a free plugin and a great way to branch out from parametric EQs.

Mistake #2: Not Learning How to Identify Frequencies by Ear

For a long time, I assumed I’d never be able to pick out problem frequencies just by listening to the sound. It seemed like the kind of thing you’re just born with, so I didn’t even bother trying to train my ears.

But with time and practice, I realized it wasn’t as hard as I’d assumed it’d be.

Identifying frequencies can be super helpful. You can pick out problem frequencies just by listening and go right for them instead of always sweeping and guessing.

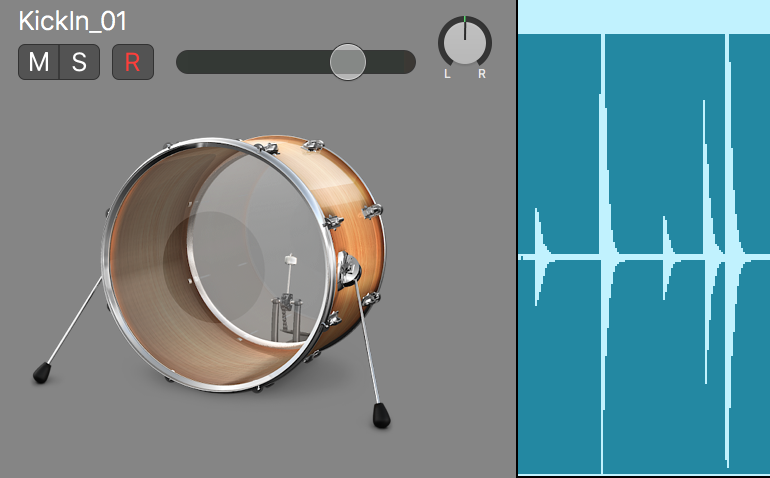

For example, this kick drum sounds a bit like someone hitting a cardboard box. Thanks to ear training, I know that I can fix that by cutting somewhere between 300 and 500 Hz.

For example, this kick drum sounds a bit like someone hitting a cardboard box. Thanks to ear training, I know that I can fix that by cutting somewhere between 300 and 500 Hz.

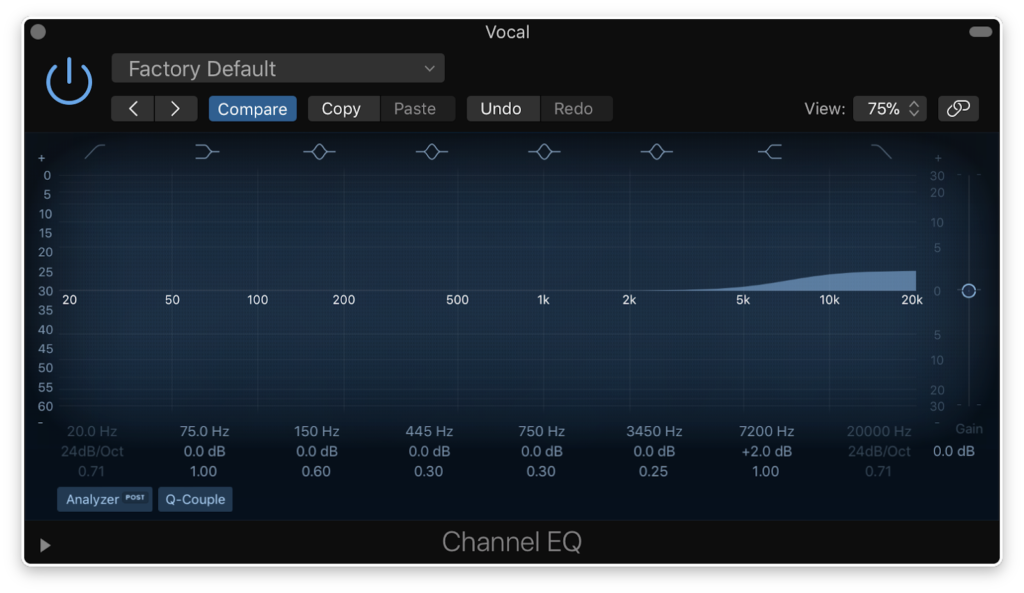

I also have a vocal take that feels really harsh and thin. If I cut somewhere in the range of 2 kHz and 5 kHz, I can probably take out a lot of that harshness.

As you can see, this isn’t an exact science. I’m just finding general areas where there are problems. But it still helps me save a lot of time.

Rather than sweeping through the entire frequency range to find where I should cut, I already know pretty much where it is.

It took me a long time to get to this point. But part of that is because I spent a lot of time assuming frequency identification was out of reach instead of training myself to do it. If I’d worked on training my ears sooner I could’ve gotten it down a lot quicker!

If you haven’t learned how to do this yet, I highly recommend using a studio ear training program like Sound Gym, Quiztones or the new Ear Training 1 course from SonicScoop’s Roger Montejano. It might seem intimidating at first, but with regular practice you can improve your hearing abilities in just a matter of months.

Mistake #3: Using Too Much EQ on Vocals

When it comes to mixing vocals, a little goes a long way. You can do a lot of damage to your mix if you don’t know when you’re boosting or cutting too much.

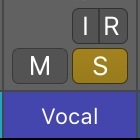

If I’m trying to get an aggressive rock vocal, I might want to turn up the presence around 2 kHz and turn down some of the mud in the low mids. In theory, this is a good idea. But early on, my EQ boosts and cuts looked a lot like this:

“But Rob, didn’t you just say you stopped using parametric EQs for a while because they discouraged you from making big boosts and cuts?”

“But Rob, didn’t you just say you stopped using parametric EQs for a while because they discouraged you from making big boosts and cuts?”

Yep! But just because you can use big boosts and cuts doesn’t mean you always need to.

Too much EQ can make your vocal sound much worse. And once the vocal sounds worse, it’s easy for that to turn into a vicious cycle. You start adding more and more EQs to “fix” the sound when the problem was too much EQ in the first place.

You want to be intentional in which frequencies you’re selecting and how much you’re boosting and cutting. If you need to turn 500 Hz down, listen carefully while making your cut. If your vocal starts to sound a little more thin and lifeless, you’ve likely cut too much.

Mistake #4: Only Using Subtractive EQ

This is a mistake I made for quite a while. After reading an article that said it was the best way to mix, I started trying to finish every mix by only using EQ to turn frequencies down, never turning them up.

If this is how you mix and it works for you, that’s great! But I’ve found I get much better results when using subtractive and additive EQ.

If I want to make a sound brighter, I can’t do that with subtractive EQ alone. I need to grab a high shelf and turn up those higher frequencies where the brightness lives.

Additive EQ is also really helpful when pocket EQing. Pocket EQing is when you make small boosts and cuts in instruments that sit in a similar frequency range to help them fit better.

Additive EQ is also really helpful when pocket EQing. Pocket EQing is when you make small boosts and cuts in instruments that sit in a similar frequency range to help them fit better.

If my piano and guitar are fighting, I can subtract 1 kHz in the guitar and boost 1 kHz in the piano to help it cut through more easily. Then I can cut 600 Hz in the piano and boost it in the guitar. That way the guitar has its own place to live as well.

Additive EQ doesn’t have to add clutter to the mix. If you use it wisely, it can help you hone in on frequency ranges that will let all of the instruments in your mix shine.

Nowadays, I usually use subtractive EQ first, often with a parametric. I’ll go through and get rid of room resonances, roll off unnecessary sub frequencies, and clean up any troublesome areas.

Once I’ve done that, I’ll load up a different EQ and turn up frequencies where I really want that instrument to shine.

I typically do more subtractive EQing than additive, but I still find the most success when combining the two.

Mistake #5: Not Knowing What You’re Trying to EQ or Why

Not having a clear goal in mind is a great way to waste a whole lot of time. Before you start EQing, make sure you know what you’re trying to EQ and why.

I used to throw EQs on every instrument even though I didn’t always have a particular problem I was trying to solve. The logic went like this: More EQ = Better Mix! I just assumed I was supposed to EQ everything.

I lost a lot of time to this mistake and it didn’t help me become a better mixer. Don’t throw an EQ on every channel just because you think you’re supposed to.

Instead, you want to be intentional when you load up an EQ. Before you start EQing a sound, make sure you have a specific reason to do so.

Think about what you’re trying to do and why you need an equalizer to do it. You’ll probably find that you don’t need an EQ as often as you think.

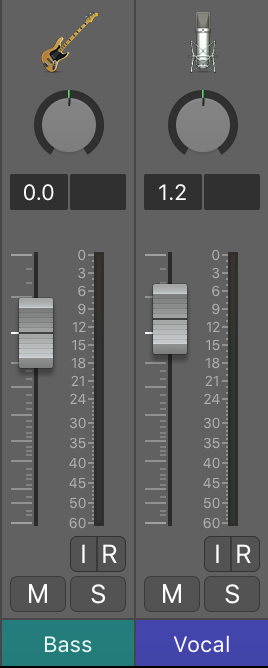

For example, imagine you’re working on an R&B track and find yourself thinking that the bass is sticking out too much and distracting from the vocal. You don’t necessarily need an EQ to solve this problem.

Ask yourself what you’re trying to accomplish: in this case, you’re trying to keep the bass in check.

Once you know what the problem is, ask yourself why you need an EQ to solve it. In this example, the solution may be as simple as turning down the volume on the bass. No need to stress over EQ, just pull back the fader and see if the bass sits better in the mix. Sometimes the fader is the best EQ.

If the the bass is inconsistent in masking the vocal, it may be a compressor you’re looking for, not an EQ at all.

Once again, training your ears will be extremely helpful when making these decisions. If you struggle with being intentional in your EQing, ear training will help you improve.

Mistake #6: Ignoring the Mix Bus

During my first five years of mixing, the mix bus may as well have not existed. If there was a problem affecting the whole mix I’d try to fix it on each and every channel.

During my first five years of mixing, the mix bus may as well have not existed. If there was a problem affecting the whole mix I’d try to fix it on each and every channel.

Don’t be afraid to use EQ on your mix bus and group busses.

If the whole mix is muddy, you don’t necessarily have to go in and fix every individual channel. Just fix it on the mix bus!

This is often the first thing I do once I’ve balanced the volume of my mix. I’ll bring up an EQ on the mix bus and see what I can do to nudge the mix in the right direction.

These are going to be pretty subtle fixes. We’re not going to go in and completely cut 5 kHz out of the mix. But we might make a small, broad cut there if the overall mix needs to sound a little more dark.

Once you’ve done this, you’re going to feel a lot more confident because the mix is already sounding better.

Once you’ve done this, you’re going to feel a lot more confident because the mix is already sounding better.

You’re also going to save time. You don’t have to keep making the same changes to each and every channel if you’ve addressed a mix wide problem by EQing the mix bus early on.

Mistake #7: Always Soloing Tracks While EQing Them

Soloing tracks while your EQing can be helpful, but you don’t want to do it all of the time.

Soloing tracks while your EQing can be helpful, but you don’t want to do it all of the time.

I still solo tracks pretty often when I’m EQing them during the prep phase. If I’m looking for room resonance in the vocal, I’m going to have a much easier time finding it if the track is soloed.

But once I’m done with prep and really get to mixing, soloing isn’t so helpful anymore. Changing the frequency content of any given instrument is also going to change the tone of the overall mix. I need to be sure the changes I’m making are pushing the mix in the right direction.

If you’re EQing the snare to make sure it doesn’t cover the vocal, you’ll want to listen to it in context of the mix to make sure you aren’t creating a new problem by accident. You might make an EQ choice that sounds good when the snare is solo’d but adds a lot of clutter when it’s played in the context of the full mix.

If you’re EQing the snare to make sure it doesn’t cover the vocal, you’ll want to listen to it in context of the mix to make sure you aren’t creating a new problem by accident. You might make an EQ choice that sounds good when the snare is solo’d but adds a lot of clutter when it’s played in the context of the full mix.

If you’re trying to EQ an instrument but you can’t hear how it’s affecting the mix, just turn up the volume on that track. I recommend doing this with a gain plugin at the end of that channel. This way you don’t risk forgetting where the fader was before and can just turn the plugin off when you’re done EQing.

Mistake #8: EQing Too Subtly

I used to think my EQ decisions had to be super subtle. I would only ever boost or cut 1-2 dB of any given frequency band.

It’s easy to get caught up on how your EQ settings look. But your listeners aren’t going to see your EQ settings and they won’t care how much 5 kHz you cut out of the electric guitar. What matters is how your EQing sounds.

So long as you’re mixing with intention there’s no incorrect way to EQ. The number of dBs you’re boosting or cutting doesn’t really matter if you have a good reason to do it.

So long as you’re mixing with intention there’s no incorrect way to EQ. The number of dBs you’re boosting or cutting doesn’t really matter if you have a good reason to do it.

If the snare needs a huge boost in the upper mids to cut through the mix, so be it. If turning something up or down 7 dB is what the mix needs, that’s fine!

Mistake #9: Buying a Ton of Plugins

I have a ton of EQs I could use when mixing. That might sound like a brag, but it’s actually a problem. It’s way more than I need.

I have a ton of EQs I could use when mixing. That might sound like a brag, but it’s actually a problem. It’s way more than I need.

Having too many plugins can get overwhelming very quickly. I got all of these plugins because I thought they’d help me get better mixes faster. But instead, I was wasting a lot of time debating which plugin to use.

You don’t need an arsenal of fancy plugins to make great mixes. Pick one or two EQs and get to know them really well.

The FabFilter Pro-Q is my personal go-to. I use other EQs every now and then when the situation calls for it, but by and large I almost always reach for the FabFilter first.

Your go-to EQ doesn’t have to be a premium one. The stock plugin in your DAW is a great option as well.

It’s way more important to be good at EQing than to have a premium EQ. You could have the best EQ in the world, but if you don’t know how to use it, it’s not going to help.

Get to know the stock EQ that comes with your DAW first before buying premium ones. When it comes to mixing, it’s not about how cool and expensive your tools are. If you know how your EQ works, you can use it make a mix sound great.

Having a go-to EQ saves me a lot of time, money, and in the heat of the mix I’m not getting distracted by options. I can focus on what I’m really trying to do: make the song sound as great as it can!

Mistake #10: Never Volume-Matching EQs

Avoiding this mistake isn’t quite as crucial as the others, but it will help you make the best possible decisions while mixing.

After you’ve EQ’d something, you’ll want to compare how the instrument sounds with the EQ on and with it off.

If you’re doing additive EQing, the volume of the instrument might be slightly louder when the EQ is on. Conversely, subtractive EQing might turn the volume down.

When something is louder, we often think it sounds better. We might get rid of a subtractive EQ that’s cleaning up some mud because we mistakenly think it sounds worse.

Volume matching is when you match the volume of the instrument when the EQ is on equal to the volume when the EQ is off.

Turn the volume coming out of your EQ up or down so the instrument is just as loud as it was when the EQ is turned off.

Once you’ve got it so the instrument’s volume sounds the same with or without the EQ, compare how it sounds with the EQ on and off. Now you can determine how well the EQ is doing what you want without being tricked by volume.

Once you’ve got it so the instrument’s volume sounds the same with or without the EQ, compare how it sounds with the EQ on and off. Now you can determine how well the EQ is doing what you want without being tricked by volume.

Mistake #11: Thinking There’s a Secret to Using EQs

I used to think there was some trade secret to EQing that I hadn’t figured out. Surely my musical heroes knew some hidden trick that was beyond me.

I used to think there was some trade secret to EQing that I hadn’t figured out. Surely my musical heroes knew some hidden trick that was beyond me.

Anytime I made an EQ decision I’d start to doubt it. “Maybe that’s too strong of a cut? Maybe I’m EQing the wrong frequency?”

It’s easy to overthink EQ. If you aren’t careful you can end up obsessing over whether or not you’re making the right EQ choices.

But, at the end of the day, EQ isn’t about numbers or formulas. You’re just trying to make the mix sound better than it did before.

Ultimately EQ is about having an intention, trying to achieve it, and moving on.

If you hear something that could be improved, do what you can to fix it and move on with your life. You’re not doing yourself any favors if you are constantly doubting the EQ decisions you’ve already made.

Focus on making the song as a whole sound good. Don’t stress too much about whether you need to cut more 400 Hz out of the acoustic guitar. Check how it sounds in the mix, decide if it’s good or if it needs help, and let it be.

There’s no secret answer. There’s no formula that you should be conforming to while mixing.

Have confidence in yourself! There’s less that separates you from world-class mixers than you might assume. Have faith in your decisions, and even if you aren’t a world renowned mixer yet, trust in your ability to create something that sounds great.

Conclusion

These 11 mistakes plagued my own mixes for quite a while. By sharing them with you, I hope you’ll be able to avoid them sooner and start getting better sounding mixes every time.

Let’s review:

Mistake #1: Only Using Parametric EQs

Mistake #2: Not Learning How to Identify Frequencies by Ear

Mistake #3: Using Too Much EQ on Vocals

Mistake #4: Only Using Subtractive EQ

Mistake #5: Not Knowing What You’re Trying to EQ or Why

Mistake #6: Ignoring the Mix Bus

Mistake #7: Always Soloing Tracks While EQing Them

Mistake #8: EQing Too Subtly

Mistake #9: Buying a Ton of Plugins

Mistake #10: Never Volume-Matching EQs

Mistake #11: Thinking There’s a Secret to Using EQs

Steer clear of these mistakes and you’ll be much happier with the mixes you create.

Rob Mayzes is an audio professional and educator who has taught thousands of people about recording and mixing through his website Musician On A Mission.

Please note: When you buy products through links on this page, we may earn an affiliate commission.