Making Money with Your Recordings Through Music Libraries

Writing and producing for music libraries is a potentially lucrative path that can provide ongoing income for musicians and producers. Learn how to get started in this field below.

In this two-part series we’re going to cover music libraries—What they are, how and why to place your music in them, and the kinds of deals they offer. We’ll review how the system works, and what you need to do to collect fees and royalties.

A bit about me: I’m an active music creator and producer who has been working with music libraries on and off since 2000. Throughout those 19 years, I’ve had compositions placed in multiple episodes of over 400 different TV series, in 3 different feature film releases, and in a national advertising campaign. All of this was essentially accomplished through music libraries.

Just What is a Music Library?

Music libraries are not a new idea. They have been around about as long as sound for picture has been, making their appearance around 1927 with the advent of “talkies”. Their offerings are more abundant now than ever before due to the advent of the internet, which has made it easy for both music library contributors and customers to conduct business.

I define a music library as a “middleman for a fee” who helps connect your music to the people who would use it for film, video, television, games and other applications. You get your music to the library, who then gets it to their clients. For this service, the library will usually take a 50% share of the income they generate, and we’ll go even more into the money side of things in part two.

The first thought that comes to your mind might be, “Why not eliminate the middleman and shop your music directly to clients?” Well, this could take a herculean effort on your part. It would start with much research, and evolve into many phone calls and emails. Then, there’s the follow-up phone calls and emails. Placing your music could easily become a part- or full-time job that might compete with your ability to actually create it.

Given the fierce competition for an industry professional’s time, you could meet with limited success when going this solo route, especially if you’re not already well-connected in an industry that has high demands for unique, custom compositions. An established library already has these contacts in place and is able to provide for all type of opportunities—worldwide. Using libraries allows composers to focus on creating music, and potentially, earn more than they could on their own.

What is Library Music?

Library music could sound like anything! Since library music is created in advance of producers’ needing it, you cannot predict which of your compositions may (or may not) be used at any given time. One of my own most successful pieces is an up-tempo African music track, and another is a “Bo Diddley”-style groove. Based on my own experience, I’d suggest that being able to create in a variety of styles is helpful to music library success.

Library music—which you might also see referred to as “production music”, “stock music”, or “royalty-free” music—is typically instrumental. This is so that in broadcast situations, lyrics do not fight with narration, on screen text, or the actors’ dialog. That is a good reason to always create an instrumental version of any vocal productions you may create.

Of course, there are exceptions to this rule: Vocal tracks are sometimes used in montage scenes or end credits, and yes, even underneath scenes with dialog.

To increase the chances that a vocal song actually gets used, lyrical content is important to consider. It’s best to avoid proper names and dates. A song about meeting someone named Lisa during Christmas time in 2012 is going to be somewhat limited in how it can be used!

For your instrumental tracks, you can increase the chances of a composition getting used by creating alternate and edited mixes, known in the business as “alts” and “edits”. An alt mix is something like a drum and bass only version, a no melody version, a no drum version and so on.

An edit refers to duration, such as a 30-second or 60-second edit. An edit can also be shortened down to the length of a brief loop or one-shot “stinger”, which can be particularly useful for intros, outros and transitions.

Choosing Libraries – Deal Focus

In order to determine which libraries are right for you to work with, you’ll first want to decide what kinds of deal structures best suits your needs, and what types of uses or “placements” best suit your music. (A “placement” is the use of a particular piece of music in a film, TV show, ad, video or other paid/professional project).

There are three main types of deal structures: “Exclusive, “Non-Exclusive” and “Work For Hire”.

Music accepted into an exclusive deal can only be represented by the single library company you sign it to. However, you may still retain ownership of your copyright.

Seeing as no one else (including yourself) is allowed to shop the music over the period of time the company has the exclusive rights, the duration of the deal is very important.

The exclusive deal most favorable to you is one with a reversion clause. That is after the specified period of time and if no placements have been procured, the rights granted revert back to you. The least favorable exclusive deal is one that is “in perpetuity” meaning you’re granting the company the exclusive rights to represent your music forever. It’s preferable to negotiate for an upfront payment in the case of “in perpetuity” agreements, and we’ll discuss that in more detail later on.

When you place your music with a library which operates under the non-exclusive model, you retain ownership of your music and are free to place the same music with other non-exclusive libraries, or to shop it for any other non-exclusive opportunities yourself.

A “Work for Hire” (WFH) deal is one in which you agree to create music and give up your copyright ownership for a predetermined fee. Seeing as you no longer own the music; the company paying you is considered its author and copyright owner in law. However, WFH contracts can allow for the original creator to collect performance royalties. More on that later as well.

Choosing Libraries – Music Focus

Once you understand the deal structures commonly offered, you’ll next need to consider how your music might best be used. Pick the library or libraries that focus on the type of uses you’ve decided your music is best suited to.

A library may focus on broadcast uses like TV shows, films, and ads. Music supervisors—the people who select appropriate music, and then secure the licenses to it—often shop here. One of the most typical broadcast uses is background music for reality TV shows. An hour long reality show like “American Pickers” which runs around 45 minutes without commercials can use 35 minutes total of background music! You can tell if your music is a fit for broadcast uses by paying attention as you’re watching TV. Listen to hear if your compositions are similar to what is being broadcast. Recently, more and more of these types of libraries are requiring exclusive deals.

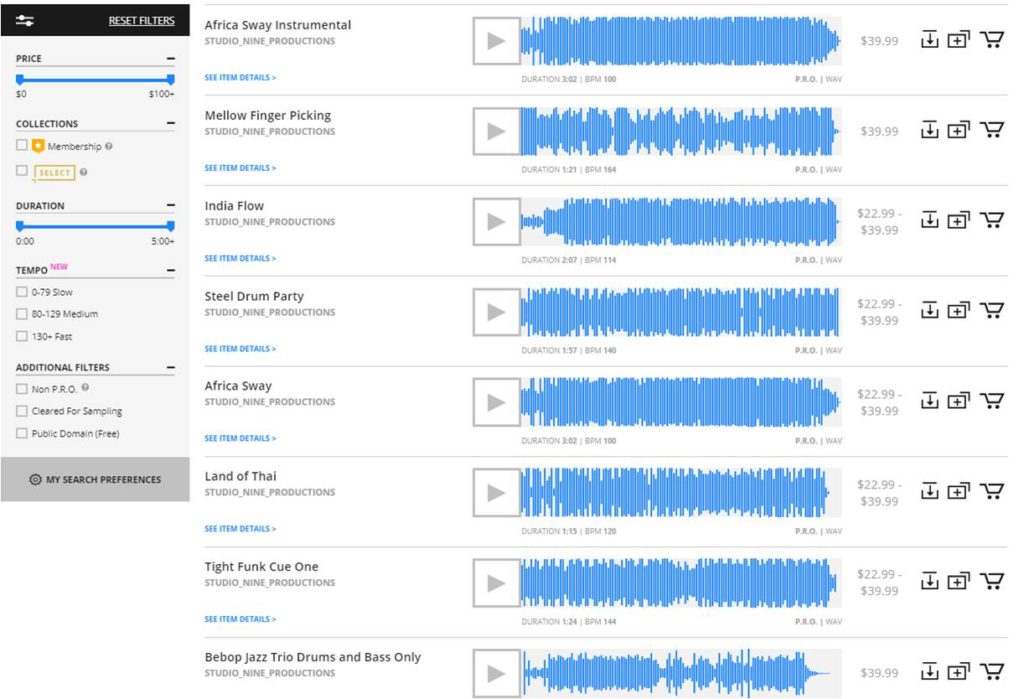

A library may also focus on non-broadcast uses like YouTube videos, corporate uses, training videos, and so on. The end users who characteristically shop here may not be full-time music supervision professionals, and typically, a non-exclusive deal will be offered to you. A library that focuses on non-broadcast uses may call themselves a “Royalty Free” or “RF” library. An RF library offers a license that allows the purchaser to use the music in multiple projects, while only paying for the music license once. In other words, the purchaser is “free” from paying an additional “royalty”. (Though performance royalties may still be collected by the songwriter if said music is used in a broadcast or public performance later on.)

RF libraries often use a simple, user-friendly “add to cart” storefront type of interface:

You can easily audition tracks at RF libraries to get a feel for what this type of production music is all about.

Submitting Your Music

After determining the deal structure and placement focus you’re most interested in, do some research to come up with a list of libraries to submit to. In addition to using the internet for research (message boards, forums, articles and so on) check the end credits of TV shows and movies. The libraries providing music to the show are usually listed there.

Each library will have their own submission process for new artists to follow. Your first step is to determine if the library is even accepting unsolicited submissions at all! Some are open to new submissions, others are not. You can usually get this information by browsing the library’s website.

Broadcast-focused libraries typically need to hear examples of your work before offering you a contract and taking on your music. Some RF libraries will audition you, others may allow you to create an account without an audition process, but will have a policy of approving each track submitted to that account.

When auditioning for a library, they will ask to hear your best work. (Not that you would send them anything other!) They want to hear completed tracks that are mixed and mastered. The means by which you will get your audition tracks to the library can vary, though most will only accept links to stream your examples. Links to download or emails with mp3 attachments will generally not be reviewed. I recently auditioned a project to a library whose process was using a web-form that uploaded the tracks to their own servers for their review.

Which pieces you should send the library for your audition is always a tricky question, especially if you create in multiple styles. If you know that the library is looking for specific music styles to fill holes in their collection then it’s easy. Obviously, if they are looking for lo-fi don’t submit your classical string quartet!

Not knowing what the library needs, or having a clear way of making contact and finding out can make it more difficult, so if they just ask for three examples of your best work, where do you start? It’s hard to say, and sometimes your own favorite track isn’t necessarily the right choice. What you love may not be best for a production library. I like to sort my catalog by date and start by considering my more recent creations. I figure the newer stuff should have the best overall sound and production values.

The opposite approach is to send in something older—a track that has been very successful for me in libraries in the past. I might also consider a musical style that has not totally flooded the market, or perhaps leaning towards tracks that use real instruments and performers in a style that not everyone else is capable of creating in.

I’ve also gone the “sampler” route, creating a five minute mp3 made up of a number of diverse 15-second to 30-second examples from my catalog. There are many different approaches. You just have to judge and decide which makes the most sense for any given opportunity!

I would be remiss if I didn’t take a second here to mention the reality of getting rejected. Being turned down from time to time is a part of moving forward in any business. If you’re not getting rejected, then you’re not submitting enough. When the rejection emails come in, simply delete them and move on! You can’t and shouldn’t take it personally. Rejection is part of the library business, and it doesn’t need to be given much weight.

Once you are accepted into a library, you’ll upload your music, following their guidelines. This can be any method from an ftp bulk upload to only being allowed to upload a few tracks at a time. The real work comes after, when it is very likely you’ll be required to enter a description, keywords and “moods” for each track. Some libraries make this easier than others, but oftentimes it is an arduous task.

A description is just that: a brief paragraph describing the piece of music. For example:

“Up-tempo and energetic, upright bass, piano and drums wind their way through a classic sounding bebop jazz piece. Their high energy will really get your listeners’ attention! Great for source music. A drums and bass only version is also available here.”

Keywords are what help get your piece noticed in a search. They can be instruments, styles or descriptive like “electric piano”, “rock”, “documentary”, and “upbeat”. Moods are words to describe the feel of the music like “melancholy”, “peaceful”, “happy”, and “calm”.

Take your time and pay attention to your descriptions, keywords and moods. Remember: No one can license your music if they can’t find it!

Coming up in part two, we’ll follow the money and learn about collecting fees and royalties. See you then!

Please note: When you buy products through links on this page, we may earn an affiliate commission.

[…] http://sonicscoop.com/2019/03/06/making-money-with-your-recordings-through-music-libraries/ Making Money with Your Recordings Through Music Libraries […]