Icons: Michael Beinhorn is Preventing Bad Music by Promoting Pre-Production

Cruising down the side streets of Los Angeles, you can expect to drive by the inevitable “Flats Fixed” operation. If you peer between the signs, however, you just may find a less typical type of maintenance available: “Song Repair.”

The proprietor of that hard-working shop? None other than super duper producer Michael Beinhorn, he who helmed signature albums for an elite artist assembly that includes Soul Asylum, Hole, Soundgarden, Ozzy Osbourne, Courtney Love, Marilyn Manson, Social Distortion, Korn, Golden Palominos, and Mew.

Between those platinum acts and his numerous other clients, Beinhorn proved to have the magic touch: worldwide, album sales of his productions total over 45 million to date. Often regarded as a relentless perfectionist, Beinhorn wasn’t afraid to make big demands of his clients, and they responded with career-defining highwater marks like Soundgarden’s Superunknown, Marilyn Manson’s Mechanical Animals, and Hole’s Celebrity Skin – the latter two of which enjoyed Top Ten debuts in the same week.

Lately, Beinhorn has been placing an increased emphasis on something beyond the finished product – or in front of it, more precisely. For him, pre-production has become paramount, and he’s striving to revive this lost art by overseeing the aforementioned song repair with tools including song analysis, project analysis and/or live rehearsal.

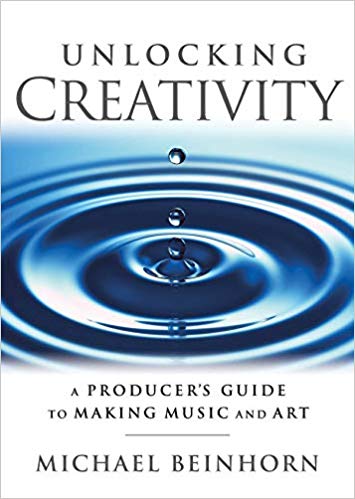

Artists of all levels are taking advantage of Beinhorn’s offerings, from emerging indies to songwriting masters like Weezer, who tapped his pre-pro services for their newly launched Black Album. For Beinhorn, who stepped out as an educator with the 2015 book Unlocking Creativity: A Producer’s Guide to Making Music and Art, it’s a natural progression into this vital new role: As a highly committed creative counselor, Michael Beinhorn just wants to make great recordings flourish.

Michael, I know mentoring is of ever-increasing importance to you. Why has mentoring become a growing theme in your life?

I feel that there’s a tremendous disconnect in terms of technical staff on a recording having the right skillsets, and also the right orientation to really work in service of an artist’s project. A lot of the focus has gone to music production as being more of a utility or like a functional process rather than an artistic one. I think it’s really important that people connect — and are able to really get in touch with — what that actually means.

This is something that you’re not going to learn from a bunch of YouTube videos. It really comes from being able to be present on an actual recording project where you can watch people work and being artists in process. The other way to do it, obviously, is to talk to people, to be in the presence of individuals who consider their work to be an art form or an artistic expression.

I’m not seeing that much of this sort of thing happening now and I have wanted for some time to make that available in whatever way that I possibly can.

When you say make that available, what are you referring to specifically? Yourself as a mentor or something else?

In every possible way, really. I’ve been working on a course about passing more of a philosophical bent on the whole recording process onto people.

That’s aside from the technical stuff, which frankly you can learn anywhere — in fact there’s no end of people who are willing to instruct in all the technical aspects of recording. There’s really no better way to pass that type of information to an artist than through pre-production.

How did you hone in on pre-production as the key to being able to transmit these values? What’s happening then that makes it such a critical time and such an opportunity to help shape what’s going on?

The best answer to that is that less and less people are actually doing pre-production on their records. I look at that and I also see simultaneously that people who listen to music seem to be less engaged with music right now. There seems to be less of an emotional engagement, that it’s more, “Oh, that’s a good melody.” They’re able to single out all of the technical aspects of a recording but they can’t really lock into the emotional aspects of it.

Pre-production gives an artist an opportunity to be able to really look at their music from a completely different perspective, to really dig into it and really question whether or not it’s working, and if it’s not working how is it not working? What can we do to fix what’s not working? Should we even be working on this particular piece of music?

When you give an artist that kind of perspective, all of a sudden everything changes. It’s like sticking a psychedelic in their face or something like that. They’ll never be able to look at life and the world and their universe the same way again. It’s really incredible to watch how this affects people. It’s almost like it infects them. It’s magical.

A Matter of Trust

You’re talking about asking certain questions that kind of break that fourth wall about the way artists think about music. How do you communicate with artists during pre-production, to get that sort of result and attention from them?

Well this is really personalized, because each artist is going to be different. I don’t necessarily have a set array of questions that I’m going to pose to an artist.

There is definitely a set array of questions that I’m going to pose to myself. The way I respond to my checklist or system or whatever it is, is really going to determine how I approach the artist. Sometimes it’s with a question, other times it’s with a statement.

It’s all really determined by what the issues in the music are, what needs to be worked on, and what part of the artist’s consciousness do we need to shift so that he or she is willing, or able I should say: Not necessarily willing but able to look at what the issues are that need to be tackled.

Is your style of pre-production only going to work with a certain type of artist? What’s the winning mindset from an artist that enters into a successful pre-production with someone like you?

I think that in that case it’s going to be mostly artists whose music is written prior to them recording it, as opposed to an artist whose music is written while they’re recording it. In a lot of electronic music, for example, some of it may be composed prior to actually beginning to record it, but for the most part a lot of the composition takes place as it’s being recorded.

If you’re talking about musical compositions that are actually stand-alone pieces that could be played with the simplest accompaniment, a voice and a guitar or piano, that’s the type of music that suits to this approach.

As far as an artist’s mindset, it really doesn’t matter. I think the only time that there’s any kind of issue is when an artist is completely resistant to any type of input at all, which is something that I have encountered, but very seldom. Even people who have blocks or resistance to something like this, what they’re really looking for is a way through them, to trust somebody like myself to come in and work with them.

How do you win that trust?

Part of what I have to do in any case is to really prove myself to an artist. I’m not taking this job on presuming that someone should work with me just because I am who I am and I have this lovely track record behind me. It’s more about, “What can I bring to you now? How can I help you now? Sure the track record looks nice but that doesn’t amount to anything if I can’t offer you viable suggestions to help take your music to the next level.”

It really is about being able to provide something viable that the artist can look at and go, “Oh, wow. That’s right. That’s absolutely right.” Once that happens, it really opens a lot of doors because it’s provable. It’s actually something where you can verify a result, because not only have you provided the artist with a solution but you’ve also given them the opportunity to take a step back. They’re like, “Oh my gosh. This is definitely trustworthy. This is trustworthy because it has opened my mind, and now all of a sudden I’m seeing things from a different perspective.”

It’s really like giving the artist an “aha” moment in a sense. It would have to wind up being multiple aha moments so they can keep watching their music take a different shape, but a shape that’s more acclimated to what they’d like it to do, or how it can be rendered most effectively.

Multiple aha-gasms, is what we’re going for here.

Yeah, I guess. That’s right!

“We’re All Artists”

Based on what you just said, are pre-production services therefore something that a young producer can offer? Because you acknowledge that a great track record can get you in the door, but that only goes so far. Is pre-production something that lends itself to helping young producers to build their credits and resumes?

Yes. As a matter of fact it’s something that at some point I’m going to be teaching as an actual skill, because I think it’s very important that people are able to employ it and that people actually apply a great deal of introspection to a record that they might produce, that they actually apply a great deal of thoughtfulness and consideration. Also, really paying attention to what it is they’re listening to.

Going back to what we were saying before about how music production is really treated these days as more of a functional thing, and how it’s even really taught in a lot of schools as being more of a functional aspect rather than artistic aspect. Being able to apply an artistic sense to something like this is so incredibly important to the process because music is an art form.

Even if you’re talking about the most basic pop music that people can make, it’s meant primarily to be an art form. It’s meant to be something expressive, something that speaks to other people, that uses the medium of sound and the medium of lyrics and melodies as a way to be able to express ideas and to express feelings.

In this, if we’re willing to take that on, we’re all artists. I would say all the greatest music that’s been made, or the largest quantity of it, has been made by people who were essentially artists. If you listen to a piece of music and you get something emotional from it and it’s something that stays with you for years and years and years, that’s art. It’s expressive.

In learning to make art, we all who are involved in the process of making this record have to be artists. If we’re going to be on the production side of a record, then it’s really important to be able to have that perspective. How can I contribute? How can I collaborate artistically on this, as opposed to my function being pressing the space bar on the computer or something like that, of placing a couple of microphones and that’s it. And at the end of the day I go home, I don’t think about this anymore.

There are more and more producers today who don’t necessarily have a musical background, with deep training. They may not know a chord progression from a treble clef, but yet they can produce music, they can produce hits, or they have that potential. If a young producer is reading this and they’re seeing what you’re saying about that artistic element, but they’re not deeply musically trained, is that an issue? How much do you really need to know about music to be able to bring that artistry to the table in a music creation setting?

I might draw some flack by saying this, but I don’t think you need to know a great deal. Honestly, I never fancied myself to be a very good musician. I knew a good deal about certain facets, but as far as being someone who went to music school and who was schooled in that way, I don’t have that. Everything that I know is pretty much self-taught or picked up from watching other people.

I do feel that if a person has this feeling for music, if they have an emotional sense of what music does and what they can make music do, how they can wield the sonic aspects of music, or if they’re a musician, how they can wield the musical aspects of music, the lyrical aspects of music, all those things to make a tangible, palpable, expressive musical statement through that medium, then as far as I’m concerned they can create something that’s as viable as anything else that anyone’s made that’s had any kind of impact at all.

It’s when you lose that connection, it’s when you don’t have that expressive connection, that’s when music starts to lose traction with people. You can see that over the continuum of recorded Western music. You can see how it kind of arcs in that way. It took a really tremendous arc after the Renaissance into the Baroque period. It started to really be about the autre and the composer, and people began to be in touch with the idea of self expression and the individual, even more and even more.

Over time we began to start losing that a little bit because other things became more important. Now I think what’s become more important is like a corporate aspect of making music, and also the technology behind making music, and the delivery systems that deliver music to people. Those things are more important in a lot of cases than the expressive component. I think that puts music at a bit of a loss.

I feel like that expressive component is something that you can’t make a real solid musical statement without, but I do feel that people who aren’t schooled, who have the right sensibility, have the right temperament, can make that kind of statement just as easily if they feel so inclined and if they’re willing to put the effort into doing it.

With Weezer: Before The Black Album

Let’s drill down into some of these principles in action with your work with Weezer on their recently released Black Album. Can you walk me through how this particular pre-production process unfolded with them?

Weezer’s Rivers Cuomo consulted with Beinhorn to brush up “The Black Album,” released March 1, 2019.

It was different than other records that I’ve done. Working this way doing pre-production, it winds up being a slightly different experience every time.

On this record he [Weezer vocalist/guitarist/songwriter Rivers Cuomo] had almost all the songs ready before I got involved and he’d actually recorded several of them and had them finished. During the time I came on board, (the lead single) “Can’t Knock the Hustle” had come out so I had nothing to do with that. My involvement on that record wasn’t for the complete album.

What I was asked to do was to provide more analysis on the music that I was hearing. I think he needed some input as far as song lengths, rhythms, and places where lyrics were kind of iffy. I was focusing on specific elements, and I wound up doing some post-production work on songs that were already recorded and were close to mixed-state or being mixed.

What that really consisted of was me giving him notes on these songs. I provided him with the notes, and the idea really was, “This is what I feel, unvarnished. Here are specifics. Here are suggestions to address what I consider as issues. Take them or leave them as you wish.”

It was more of a situation where I’m not necessarily the final arbiter. That said, I think on most records that I’m going to pre-produce, I’m not necessarily the final arbiter anyway. He had a concept for this record. It was already in process. My input at that point is going to be present but I wouldn’t say that it’s going to be massively significant. It did affect the length of some of the songs. It did affect some of the rhythmic approaches. Definitely lyrical stuff, and on some songs more than others. Some of them were further along than others. It was definitely a mixed bag.

Obviously, it’s different working with an artist who has been pretty well-established for many years, as opposed to a lot of other artists I might work with who are far less established. It’s a much different dynamic, and in addition to which he’s already working with a producer [Dave Sitek]. Again, that affects the dynamic there as well.

Breaking Down the Process

Can you give me a walkthrough of the pre-production process as you see it, as you’re envisioning it, maybe as you’re trying to instruct it. What’s a way that it would unfold in its fullest form, as you’re discussing it?

It’s really simple actually. The first step is obviously for me to listen to music and for me to get a sense of if I really feel that I can provide some kind of assistance on it, because obviously if I can’t do anything for an artist, I’m not going to waste their time nor am I going to want to waste mine. I’ve got to see if I can actually be of help.

Once I’ve established that that’s the case, then I have to sit down with the music, and I’ll usually listen to it a whole bunch and basically outline all the places that I feel there are problems. As I listen more, I can see where those problems have compounded and perhaps created other problems. Like anything that winds up being systemic like that, it can affect other elements in the song. These can be very subtle things.

One thing that I do notice consistently these days is that people don’t do decent transitions from one section to the next, like there’s very little set up. Dynamics can be an issue, a lot of times drum beats are off. The way I’m looking at a drum beat is not so much whether it’s just a cool groove, but how it’s supportive to the rest of the instruments, particularly to vocal one. If bass drum accents aren’t supportive to a vocal melody then, from my perspective, you’ve got an issue. The same is true of bass guitar, with bass notes. Where the roots fall, how they fall, what kind of rhythm is this?

As I’m sure you can see from what I’m describing, I’m going into this at as much of a granular level as I possibly can, to really take the whole structure apart, dissect it.

What else are you’re searching for as you go?

What I look for when I’m doing this is a disconnect. The way I identify a disconnect is when my attention span while I’m listening to a piece of music starts to waiver. If I lose my point of focus with a song, then I know something’s wrong.

The last thing you should be doing when you listen to a piece of music is going elsewhere, paying attention to what’s happening out the window or something like that or, “Oh god, I didn’t pay my gas bill.” You should be locked in the entire time. If I’m noticing that I’ve gotten thrown off my focus while I’m listening to a piece of music then I have to go back and see if it happens again.

Then it’s on me to figure out why that happens. What is it that’s making me not want to focus on this anymore? It’s interesting, once you start listening to music that way and you start noticing all the little places where you lose focus, then you begin to see how you can help an artist make their songs better.

That’s a very interesting standard, and quite reasonable. I haven’t quite thought about music in that particular way, that effect on me.

It’s one of many. It’s one of a few standards that I’ll employ when I’m listening to music, but it’s good because we do tend to listen passively to music anyway, and it’s easy when you listen passively, and you’re watching yourself listen passively, if you can objectify the whole process, then you can actually see yourself losing your attention span. That’s an interesting practice in and of itself.

Once I’ve done that, then I’m going to compose a whole bunch of notes. As you can imagine, they get pretty extensive. They can go on for quite a while, but it’s all purposeful stuff. I’ll impart that to the artist and we pretty much go from there.

Buyers and Sellers

This has been something that I know you’ve been talking about more and more, in various ways, including in your book as well. What do you think is more important: Convincing producers of the importance of providing pre-production, or artists of the importance of receiving this service?

I don’t think I’m in any position to convince any other producers of anything. They have to walk their own path, so to speak. I would like to think that producers are applying a standard of pre-production to their recordings. Of course I do know of a lot of people that I’ve worked with who are genuinely surprised by the idea of pre-production, which in turn surprises me because I can’t imagine making a record without it.

If a producer feels that there’s a need for it, great. If they feel that they can go into a recording studio and kind of wing it, that’s their business. I can’t speak to how other people approach projects.

Artists on the other hand, I can state without any question at all that it’s something that they need desperately. Unless they’re someone like Muddy Waters who can write a song in 15 minutes and then just walk right into Chess Studios, sit down with a guitar, someone hooks a mic up, he records it, boom, you’ve got “Rollin’ Stone” or something like that. There ain’t no Muddy Waters guys out there anymore.

So you’re saying that artists are going to drive this market — it’s up to artists to understand the importance of this and start seeking it out. Then these gigs are going to start to come up more and more for producers. Is that right?

I think at this point it’s really up to me to be able to speak with enough efficacy about how important this is and for people to come in contact with that and to be convinced, I would hope, by the quality of the work, by the fact that it just makes complete sense, and because you actually can look around and see how music seems to be connecting a lot less emotionally, how people really kind of have come into this mindset of, “We’ve got a batch of songs. Let’s just run into a recording studio and put them down, instead of, “Okay, we’ve got a batch of songs. I think that we should sit with them and see if we can get the best out of them that we can.”

There are tons and tons of artists that I can point to who would write a song and then sit on it, sometimes for months, sometimes for years because it either didn’t fit with the body of music that they were getting ready to record at that point in time, or they just didn’t feel that they had the right treatment for the song yet.

What’s a prior instance of this that you like to point to?

Led Zeppelin is a perfect example of this. There are recordings of them working through different pieces of music, some of which they would put aside for a long time until they had them just where they wanted them. I think it’s incredibly important for artists to be able to take the time that they need to be able to get their music to sit exactly the way they want it to. I feel that it’s the logic of a statement like that which ultimately drives this thing.

The comments that I hear on a fairly regular basis now, not coming from people who happen to be my age either, saying, “Why isn’t music that great anymore? Why am I having a hard time getting anything from it? It all sounds the same. Blah blah blah blah blah.” Well, it’s because people aren’t really thinking carefully when they’re creating it. They’re not thinking before they go into a recording studio. They’re not giving it a chance to percolate, for them to look at it and go, “Is this what I really want to be saying?” Or, “Is this an accurate reflection of who I am?”

So Michael, you’re talking about convincing artists and making this case to them, and so that comes down to demonstrating the benefits. Some of the benefits, as you’ve just pointed out, are that the songs themselves that you’re working on at that time will be better. Will undergoing this process also make them better songwriters? Will going through this process, in theory, help them to sharpen up their next round of songs?

Anyone who is going to seriously apply themselves to their craft, especially if they have talent beforehand, can’t help but get better if they’re going to apply themselves at this level. I have countless examples of this.

Also, I should point out that I feel that in the long run this process is worthwhile to other producers in that if I’m working on pre-production for another producer, it essentially takes care of a good deal of the heavy lifting that they might have otherwise had to do themselves, and lets them focus on the recording aspect of it.

That’s a great point. That leads to another question that I had. Does being a pre-production producer on a project disqualify you from being the producer? Can you be both? Why or why not?

Really, being able to do both means that I have been hired to produce the record in the first place. If I’m working with an artist just to do pre-production, I’ve essentially disqualified myself. I’m basically saying, “This is what I’m going to do. This is my job. After I’m done with this, you can record what you need to record with whomever you want to do it, and you will essentially have something that you can roll straight into a recording studio with, and with maybe a few small changes perhaps, if that’s even necessary, just do everything from top to bottom.” It’s an immense time-saving device as well.

That heads right into my next question, which was how do you convince artists to invest the additional time and expense into the pre-production process? You’re saying, just like in Moonstruck, “It costs money because it saves money,” right?

I never heard that. I guess you’ve done a better job of summing it up than I ever could. The thing is that compared to what an artist is going to spend on the overall production of their record, it’s not really a tremendous expenditure. It still costs something, and that’s an issue for a lot of people since there is very little money to work with in a lot of cases to actually make the recording.

In the end, as you said, it does save money. It saves time at the recording end, which is where most of the money is going to get spent for the recording anyway.

Studio Perfectionist

Looking back on your career, at one point you had a reputation of being an extremely demanding producer. Do you feel that reputation was deserved? Did you want to be seen that way then? How would you characterize your approach today?

(laughs) I don’t think I wanted to be seen like that, it’s just what wound up happening. It wasn’t that conscious. I didn’t go into it going like, “I’m going to be the El Exigente of music production,” or anything like that.

It wasn’t something that I consciously sought. To tell you the truth, it’s one reason why I don’t think I’m producing as much now because I think people do want a certain amount of pliancy and they want to get results very quickly.

I’m not of that school. I enjoy working a little harder to get something that’s going to be very personalized to a recording project, to the artist. Something where you’re able to use the sonics of the medium to really help tell the story, and to be able to express who the artist is. That doesn’t involve a rote approach, which I think most people are willing to take now because it does get results and it gets the job done much quicker.

It sounds like that it would be a much better fit to take that kind of personality and perspective into the pre-production then. This is a perfectionism that you can employ during your own personal listening process and how you communicate it, right? What they choose to do with that feedback from there is up to them. That’s just how I’m processing that.

I think you’ve got a good processor.

What are some of your favorite studios are to record or mix in right now — where do you like to go and work when you get the chance?

Well, out here [in Los Angeles] I’ve always liked Conway. The big room at Conway, although they don’t have that SSL in there anymore, that was such a wonderful room with that SSL. I like some of the rooms at Henson, like studios D&B.

I think at this point, if I could go anywhere to work, it would probably be Studio Guillaume Tell in Paris. As long, of course, as they have an SSL in there. I just have a thing for those consoles for recording. I tend to bring a lot of my own stuff with me, and SSL’s tend to interact with the kind of outboard that I work with really, really nicely.

What is that? What are some of the pieces you’re talking about?

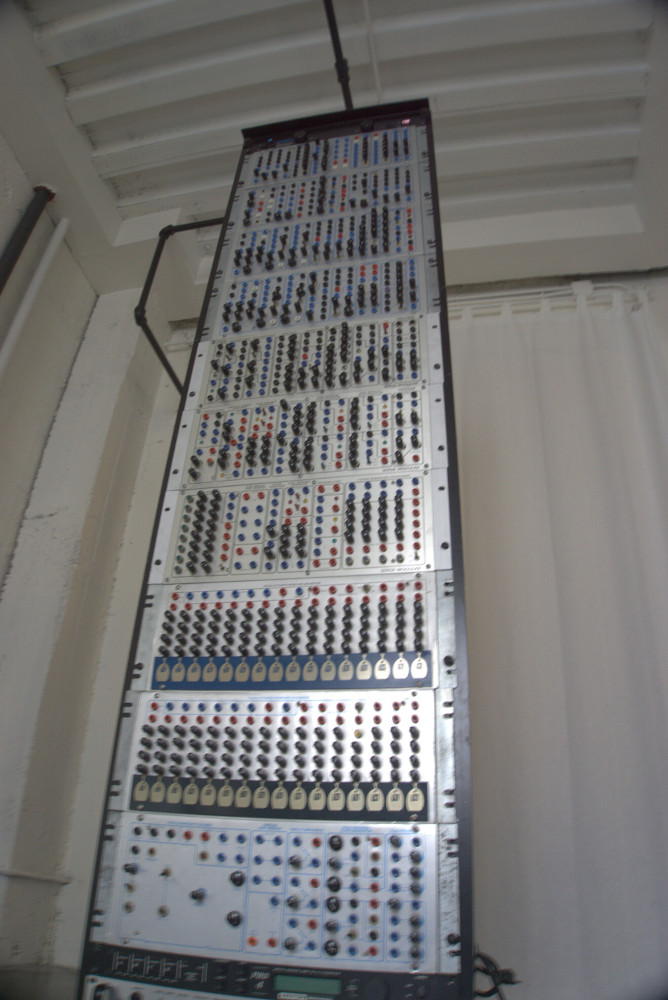

Really at the heart of it is a bunch of old Germanian Neve pieces. I’ve got what I think is the world’s largest collection of Neve 1057’s. I’ve got a set of 16 that came out of a console, which I was told was the first console to actually make it to the United States from England. Of course no one’s going to be able to prove that one way or the other, but these are old modules. They predate what most people use. There’s just really nothing like them in the world. The drums on Soundgarden’s Superunknown, it’s almost all 1057’s.

I also have a set of four Neve 1058’s which is the same exact circuitry, but the topology is a little different. It’s a switched mid band and sweepable high and low band. These don’t sound like most other 1058’s because they don’t have the St. Ives transformers. Wait. Not St. Ives. What were the big ones?

I don’t know either.

They’re enormous, those original transformers- they’re called Gardners. I think they weigh about a pound each or something like that, or two pounds. They’re ridiculous. My 1058’s were racked with Marinairs — instead of the original Gardner transformers — on the output stage only. It does something really cool to the sound of these things. They’re magical for guitars

and basses. It’s absolutely amazing.

The tonality of the Germanian stuff is so different from the later silicon stuff because it’s real gritty. It’s really, really gritty and dirty and rich. I always find the silicon stuff to be a little bit smoother and smearier. They’re all kind of smeary, but it’s a different kind of smear. This stuff, because there’s so much grit to it, it’s kind of a little bit more distinct in a funny way. I can’t really explain it properly. I love these things so much. I’ve never heard anything that sounds better on drums.

The guitar and the bass on Superunknown, that’s all these 1058’s. I don’t think I used any other rack piece for any of that recording. I think for the high hat mic we used the SSL mic pres. I’m pretty sure that was about it. Everything else was Germanian. That whole record is just Germanian Neve, except for the vocals.

And on another note I also like some of the API stuff, the old API stuff and the DeMedio API stuff in particular sounds really, really wonderful. I’ve got four of those as well. I really like those a lot. They’re fantastic.

The Road Less Traveled By

Here’s my last question, Michael. The music industry itself is undergoing a great deal of change, both creatively and technologically. What’s your advice for a young producer who’s getting into the game? What opportunities do you see that they have?

There’s so many ways to answer that, especially because of the nature of the business right now. It’s kind of like the Wild West out there. I think that you’re going to get different advice from different people about what to do, and I don’t think that you’re going to get anything consistent, which is unfortunate.

If you’re asking me, I can tell you you’ve basically got two roads as someone starting out. Either you conform to every known standard that’s lobbed at you by people who are in the industry, so that you basically become as attractive to them as possible by following all the trends and every arbitrary approach to production that you can. Learn how to use the plugins, learn how to grid all your drum parts, learn how to sample drums and make sure that you can get an entire record done in 15 days, in a day even, just so that you can get work.

Or the other option is to know all that stuff but to completely buck it and just say, “I need to find out who I am, why I’m doing this.” If I feel like I’m an artist, what it is that I’m trying to express, and how I’m going to be using this technology to express what it is that I need to say, which is a whole different way of approaching this type of work.

It’s something that most other people are not going to do because it involves a lot of soul searching, a lot of introspection. It necessitates a level of technical expertise that goes beyond what most people are willing to accept, before they can rush out into the field and say, “Hey, I should be producing your records.”

Obviously you have to have interpersonal skills then. You have to be able to be in a recording studio and know how to make the artist feel good. Also, to know how to talk to artists. It does help if you have some kind of musical background. It’s not 100% essential, but if you’re going to be talking to musicians about what they’re doing, you sort of need to know some of the lingo, because you don’t want to come across looking like a complete moron, because people aren’t going to trust you then.

Moving from the studio, how about the business aspect of things?

As far as the business, it’s a necessary evil and it’s something that you’ll have to deal with, especially if you’re going to be working on larger budget records over time. One thing that people in this business love more than a producer who will do exactly what they want, who will follow all the trends — like the first example I gave — is a producer who can sell a shitload of records.

From my perspective, you can be successful as someone who kind of follows the party line, but you can also be mindbogglingly successful as someone who’s more iconoclastic, who sort of marches to the beat of his own drummer, and of course takes a riskier road. Ultimately that’s a more fulfilling way to go. That’s been my experience.

On the flip side, what do emerging producers need to be cautious about?

One thing that it’s important to watch out for I think is lots of different ways that people will try and separate you from your money to teach you all the ins and outs of how to do this kind of stuff. Getting too caught up in your head about what you’re doing, having it become more of a cerebral thing to the point where you really kind of separate yourself from the music that you’re working on instead of developing a really deep, emotional relationship with the music that you’re working on.

As a producer you have a different relationship with an artist’s music, unless you’re writing it with them. The truth is that you can get deeply, deeply emotionally attached to something, which isn’t a bad thing if it means that you’re going to invest a good deal of yourself.

It does become a bad thing when you start making ridiculous judgments because you become too subjectively engaged with it. If you’re able to maintain your objectivity and still have the ability to make sound artistic judgments, you can kind of be in this crazy, crazy intense relationship with this music and then when the record is done, it’s over. It’s basically like having a different girlfriend or boyfriend every few months or something like that, or every half year, however long a record goes on for.

Whoa.

You have these really intense relationships. I know. It’s crazy, right?

I don’t think it’s crazy, it’s just deep and just a totally different way to look at it.

It’s really cool, actually. We can have such a good time and we can get a little bit wilder with the music if we’re able to look at it from that perspective. If it becomes something like that, then it’s like, “Wow. How far do you want to go? What do you really want to try? The sky’s the limit.” “I don’t know, I’m up for anything. I just want this to be great.”

In the end of it, if you’ve created something that has a lasting value, where the people who hear it have the same connection to it that you had while you were making it, holy mackerel: That’s the stuff that lives on forever. To me that’s more important than just you having a job and getting it done. Anyone can do that. Drive for Uber if you want that.

If you turn being a record producer into being an artist where you’re really unfettered and free, you can just scale these unbelievable heights, and you can do it with other people’s music, so that it becomes a collaboration. It’s a really beautiful marriage. It’s one of the best things in the world. It’s rewarding on every possible level.

— David Weiss

Please note: When you buy products through links on this page, we may earn an affiliate commission.

[…] http://sonicscoop.com/2019/04/15/icons-michael-beinhorn-is-preventing-bad-music-by-promoting-pre-pr… Icons: Michael Beinhorn is Preventing Bad Music by Promoting Pre-Production […]

[…] Bands Fought Back (OpenCulture.com) * The Shape-Shifting Music of Tyshawn Sorey (The New Yorker) * Icons: Michael Beinhorn is Preventing Bad Music by Promoting Pre-Production (SonicScoop.com) * A Visit to John Cage’s 639-Year Organ Composition (RedBullMusicAcademy.com) * Chris Potter […]