Icons: Lu Diaz — Clearly the Best Mixer for DJ Khaled, Morgan Heritage and More

Depth. Power. Punch. Clarity.

Prepare to experience all that and more from a Lu Diaz mix. An integral part of the Miami modern music movement and one-half of the famed production duo The Diaz Brothers, Lu has always been about breaking through, both in the music business and sonic quality.

For proof of his skills, look to his discography, then sit back and listen. Spanning the best of hip hop and reggae, his platinum and GRAMMY-winning track record is built on the likes of DJ Khaled, Beyoncé, The Baha Men, P Diddy, 50 Cent, Juvenile, Beenie Man, Trick Daddy, Lil Jon, Toni Braxton, Mary J Blige, Lauryn Hill, Nas, and many more. Diaz’ work was up for a GRAMMY in 2018 with reggae elites Morgan Heritage’s Avrekedabra. Plus, together with brother Hugo he discovered Pitbull.

As you’ll see, the affable Diaz didn’t take a conventional path to his success. Instead, it was a harmonic convergence of hard work, right place/right time luck, and a lifelong love of learning that made him not only a hit mixer, but a valued artistic collaborator with his clients.

What makes a mix from Lu cut through? He’s got no secrets, so simply read on to tap into his platinum talent. (Keep track of Lu Diaz at The Best Mix Engineer and on Instagram at @iamludiaz.

Lu, how did your mixing career begin? Let us know your backstory.

The thing for me is I’m probably the most unconventional guy. I’m sure there’s people out there like me, but the majority of people go to school, do the intern thing, go to a studio and grow through there.

Mine was a little backwards. I actually started as a musician in a band, and then that got me into sound. I wanted my drums to sound good, and I realized I had a knack for making my drums sound right in my monitors. Soon after that time, I started a record label, I was 18 and I learned the music business “Hard Knocks” style. In putting records out, I started producing my own records, and I learned the studio side of it, and then I kind of fell into engineering.

My younger brother [Hugo], had actually gotten a record deal with a group he was developing and producing. Yes, he got the bug as well. I helped him record the songs, put them together sonically, and they went on to get a deal with Atlantic Records.

I never thought about being an engineer or even considered being a mix engineer, so when he presented it to the label, they asked who should mix it, and I referred a mix engineer that I would use to mix my projects, his name is Carlos Santos. He was a real prominent engineer back then here in Miami. He mixed the record, but the thing was, Carlos came from more of a dance / pop background, and this was a reggae dance hall project.

I guess they got married to the roughs, because they were like, “Who mixed these roughs?” and that’s how I got my first gig, which was crazy. That was in the mid- to late-‘90’s. That’s actually what made me think, “Maybe I can do this.” That’s where it all started.

So it really wasn’t something you had considered? Did it occur to you at the time then, that you liked mixing? What appealed to you about it?

The thing is, even prior to that, I was always very into audio, and just generally was obsessed with gear. I loved the whole studio thing, it was really cool, but I never thought to myself, “This is what I want to do as a career.” I really started off as a musician, and then kind of dabbled in the label thing and the audio thing just kind of spoke to me along the way. So because of that opportunity with my brother, I realized that I could actually make it a career.

Long story short, I ended up really going back to recording, but I never assisted, I just jumped right into recording. I was like a recording/mixer for a while until I got my stripes and got more comfortable.

How did you actually begin to build your catalog? One day you’re a mixer — did the projects start flying in the door?

Partners in rhyme — Diaz (l) with Pitbull. The Diaz Brothers were Executive Producers and Music Producers for Pitbull’s debut album M.I.A.M.I.

What’s funny, looking back on it now, I think I was just naïve. I had no idea that mixing was a big deal. If I’m being perfectly honest, when I sat down at Soundtrack Studios in New York I was like, “Alright, how do you turn this thing on?” Lol!! That’s it basically. I had a knack for it. Obviously I listen to those mixes now and I cringe, but I learned a lot from that experience.

That actually sparked more developments. The guy who was involved in that project was a guy named Peter Thomas, who is actually now semi-famous, he’s a cast member on the reality series “Real Housewives of Atlanta.” He was working with Def Jam and Atlantic at the time, and after that K-Squad project he said to me, “You know what, let me hire you for this other gig for Def Jam.” It wasn’t that I had a name in the industry, it was just that we built a working relationship and he dug my work, so he continued giving me gigs.

I got home to Miami and he said we have to do a recall one of the mixes, because the artist mentioned Mike Tyson’s name on a line in the song and the label wanted it replaced or something like that. He said, “I need you to go to my friend’s house in Miami.” I scratched my head thinking this friend must have a hell of a studio in his house, but the house turned out to be Circle House Studios in Miami.

They had just built the place and I kind of just stumbled in. I had an immediate connection with the studio and the band. That’s where I really got my first shot at this recording and mixing thing. Circle House gave me a place to hone my skills and grow. They took me under their wing, and allowed me to grow with them.

It was a bit of luck. I happened to be in the right place at the right time, and like I said I grew with that studio. That’s where I got my first big credits, and started recording and working with big artists. The studio and the band, Inner Circle, really gave me a shot, you know?

Career Takeoff

What turned out to be your breakout mix? What really put you on the map?

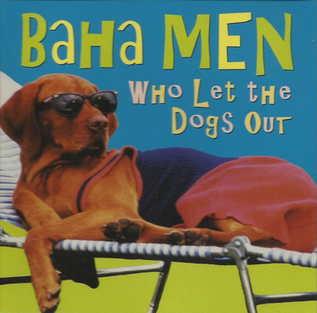

Early on I worked on a song called “Who Let The Dogs Out” [by the Baha Men] which as you probably know got ridiculously big. That song gave me a lot of exposure which led to working with Cash Money, Mary J Blige, Lauryn Hill and so on. It was really more the collection of the names of the people I was working with.

But what really gave me a solid name in the urban world, was “I’m So Hood” by DJ Khaled [featuring T-Pain, Trick Daddy, Rick Ross and Plies] from the 2007 Album We the Best. That record I remember, I was getting calls from people like, “Wow, I heard that in the club and that snare and kick.” I remember thinking, “This is really going to give me some notoriety,” that was a big song at the time. Now as far as a worldwide hit, again it was with DJ Khaled, “All I Do Is Win” (from the 2010 album Victory).

There were so many other big names and projects during those days, sometimes it felt like a revolving door. I was working around the clock back then, it was crazy. Since then I’ve worked on pretty much all of Khaled’s records with the exception of a couple.

As these things start to take off, did you start to feel that you were growing as a mixer? What did you start to understand about the craft of mixing as you got better, as you started to get some hits?

Definitely I started growing. You know what it is? I tell people it’s repetition, practice. You slowly start making distinctions.

I always say, “If someone gives you five tennis balls and says, ‘Start juggling,’ and you juggle every day of every year for five years straight, you’re going to be a pretty damn good juggler.”

That’s pretty much what it was for those five years. As I was going, I was discerning different things, and pretty much saving ideas, and tricks, and things that I did and didn’t work. During that time the technology was making huge changes, with the introduction of Pro Tools and digital audio.

My career happened to be growing during this time and the changes felt hyper fast, because what was working for me a year ago was suddenly changing completely into a digital world. I was a very early adopter of Pro Tools and was definitely part of the first wave of mixers that went in the box. I really embraced it. I was learning so much, so fast it was awesome, as every year passed, it literally felt exponential in what I was learning and what I could achieve.

The Miami Mix

Right. How would you describe the Miami scene? Why is this a good place for a mixer to be based out of, or at least for you?

Yeah. I mean, for me, it’s very personal in the sense that I grew up here. It’s my hometown. It just so happened that when I started the whole engineering thing, I was very fortunate to be part of a musical movement that was happening in Miami.

New York always had a wave, LA had a wave, Atlanta had a wave, where they would put out a string of successful artists. In 2004 my brother and I (The Diaz Brothers) signed Pitbull. That kind of kicked off the Miami wave. Although Slip-N-Slide Records already had Trick and Trina in the scene and Uncle Luke was a huge part of Miami, it wasn’t till Mr. 305 really drew attention to our city. After we broke Pit, E-Class (Poe Boy Records) broke Rick Ross and Flo Rida, DJ Khaled dropped the We The Best Album, Cool & Dre became established producers and Jim Jonsin produced a slew of top 10 songs. We were all a part of this new Miami wave.

Now, not only is the weather great in Miami, it’s also the mixture of cultures and music. I’m generally known for working on urban records, but here in Miami I’ve had the pleasure of working with a variety of musical styles like reggae, Reggaeton, Junkanoo and Latin music. Miami really is a melting pot, I love this city.

Are you mixing out of your own studio?

I’m very spoiled now, because the majority of my clients send me the files, I start working on the mixes in my home studio and really go in to a big room with my clients to make the final changes. I still like to go into the studio with people, but I think that a lot of my clients see the benefit of letting me live with the material for a while.

I assemble my mix sessions and do whatever other tech things I may need to do, and then I get the mixes to about 90% of the way there. The time I’m in the studio with my clients we are basically at the finish line. So as far as they’re concerned the mix process gets condensed into a short five-day-week or so, in a perfect world lol!

That’s pretty much where I’m at now. I’m very non-localized. I travel a lot more because now I’m able to sort of move my mix in my laptop, but that’s pretty much where I am. I’d say about 85-90% of the work I do, I do at home.

So you’ve got a home mixing setup. What’s that like? Do you have an analog console? Are you only working off your laptop?

I’m completely in the box, Pro Tools HD. When I first built my room it wasn’t even intended to be a mix room. I had built the room to be more of a producer’s writer’s room, and it was supposed to be something to go there, create, and just to make music and that kind of thing.

As time passed, little by little I started prepping mixes, and I couldn’t help it. We’re in new space now, where mixers are mixing in their own studios more and more, and I’m a part of that. So the room kind of worked backwards. I treated it, gutted it, rebuilt it again. I recently sold that house and now I’m planning on possibly building a room in Atlanta. I still have a place here in Miami and I’m still based out of Miami, but my wife has a career in television and we need to be in Atlanta a lot. So the plan is to build a room in Atlanta so that I have a home base studio while I’m there as well.

Take it to the Limiter

How you would you characterize your approach to mixing, and what are some of the ways you achieve those results?

I’m very aggressive and loud, that’s just my thing. One of techniques would be that when I mix a song, I like putting a limiter on the master.

People think I’m crazy, but I’m sure other guys do it. It doesn’t matter the limiter, it’s just choice of flavor. If you like the Waves L2 Ultramaximizer, whatever it is you use, I just like the preview. Obviously that’s not what the masters are going to sound like coming back from mastering, but it gives me a good round about idea of what I’m doing without it, and what the mix sounds like with it. I do a lot of A/Bing of my mix, with limiter and without.

Although I think we’re starting to come off this crazy loudness war, I still find that it’s very important that the mixes fit within that crushed mastering sound. It’s a technique that allows me to maintain perspective and balance.

I realize a lot of times, less is more and sometimes you got to let the limiter do the work, right? I see some guys get so wrapped up in mixing, and they don’t understand once you pop a limiter on there, or send it off to master, your whole mix changes and so many new artifacts jump right out. To me, that’s a really good tool to sort of get yourself used to. I’m sure for some people, it could be a nightmare, but for me it works. It always gets me to that point, and allows me to squeeze so much more into a mix.

What limiter do you use, and what do you set it at?

Well, it varies. I’m a big fan of iZotope Ozone. Right now I’m on 7, I’m about to jump on 8. I love iZotope. The L2 has been the standard forever, so whenever all else fails I’ll throw an L2 on there. For the most part, I like the transparency of the limiter in iZotope. I’ve been on Ozone since version 5.

When you deliver the mix, do you then take the limiter off? Is it just there for your reference?

It’s only there for my reference. That’s the thing, it’s not that I’m squashing the mix the entire time. It’s really for a preview. Like I said, I’ll pop it on and listen. I’m checking to see what I did and how it worked through the limiter.

What I’ll do for clients like Khaled, who want to leave the session with a mix ready to be played in a club, I have to have it sitting there ready. It serves a purpose where he’s in the studio as well. He can listen to the mix as loud and limited as he wants, and when he steps out, I can turn the limiter off and go back to what I was doing. When I deliver it [to mastering], obviously I deliver it without the limiter.

The mastering guys that I work with, like Chris Athens, Mike Fuller and Jose Blanco, I’ve had a long working relationship with those guys. They already know that I’m going to send a limited version for their reference. Depending on the client, they understand where we need to be. As you work together over the years, they get to know you, and they give you what you’re looking for.

It’s funny you talk about how aggressive your mixes are, because what really stood out to me was the clarity I heard, and just how I really felt like I could hear everything that was going on. How do you achieve that? Does that come from simple things, just like levels, and balancing?

A little bit, yeah. You know what it is? The thing I can attribute it to is, I always start with the drums and bass. To me that is the foundation. Once I get that under control, fixed, or where it just sits good, then as I start putting stuff on, a lot of the times I’ll put a lot of attention on small sounds, or even little subtle effects.

What I’ll do is I tend to mix very loud, and it’s not good for me I know, but it’s almost my zoom tool. Let’s say I have sound that may not be insignificant but just not as important in the mix, I solo it and listen at a pretty loud level, and just tailor it without thinking about how it fits into the mix. I just want to make it as clear, and as pleasant to me, and then I decide where to place it with levels.

For example, I’ll take a cowbell that’s very light in the mix, but when I work on it, I work on it loud and I hear it. I want to see what I’m doing to it or taking away from it, and I get it set to where it would sound great cranked on its own. Once I’m done, I put it back in the mix and I find a sweet spot for it pan it, and level it in.

That’s what makes for a lot of detail in some of my mixes, I try to sort of tailor or touch every sound.

How about vocals, in particular? What’s your approach there?

That’s where I would say I’m very aggressive, well in the sense, my first approach is always to fix problem frequencies and then I start to mix and enhance. I listen for frequencies that just plain bother me. At a nice loud level, I’ll immediately zone in on what frequencies bother me. A very common area of most vocals is at that 1K. So I’ll isolating that frequency and pull it back with EQ, and multiband compression.

People always ask me, “What should I set my multiband settings to?” I’m like, “I don’t know. You’ve got to go find those frequencies and then pull them back.” Once you isolate those frequencies things will start to sound under control, it really is a process.

At the end of my vocal chain I like to squash the vocal a bit. Not where it sounds nasally and over-compressed, but I like to be able to push that vocal into the very front of the mix. Sometimes people are like, “That’s too far front,” but I like that. I like when the vocal is sitting right in front of you.

“Major Key” Communication

DJ Khaled’s 2016 album Major Key is so inventive all the way through. What’s the communication you had with Khaled for that? How did you and the artist talk about that album, or does he just say go ahead and do it?

We’ve been working so long together. Khaled and I started working in 2004-ish on an album that never was released and then led to working on his official debut album Listennn… in 2006. Khaled is a very interesting, intense dude. I don’t want to say that there’s any sort of routine that we go through, but we definitely have developed a sort of tempo and system on how we go about mixing. He’s very secretive about who he has on his records, and although he has a high level of trust with me, he only lets me hear the final arrangement, when it’s go go time (laughs)!

I’ll give you an example. Khaled sends me the beat files for a single “Shining” before his writers even write to it, he’ll have me rough mix it so the vibe is right. They’ll write over that rough mix, record it over that rough mix, and then send it back to me to mix it some more and get the ref vocals sounding tight. He then presents it to the artist and after they record it and he’s fully done putting the “sprinkles on it” I get the session back with the artist on it (Beyonce and Jay-Z). It’s just the way we work. Not that he does this with every song, but for the songs he considers his bigger one this is the process.

How do things change for you when you’re doing a reggae album, as opposed to an urban record? You just told me kind of some of the guidelines you set for yourself and the ways you do it. Does that change if you’re doing something like the Strictly Roots album from Morgan Heritage, or anything like that?

Not so much because of the style of music. Obviously it will a little different if I was doing, say, a country album, or a ballad. But I think it’s more on the type of artist. For example, Morgan Heritage is an actual live band. Obviously, there’s programmed drums on the album, but they’re more earthy. The approach changes in that sense, with dealing with live drums, guitars, and things like that.

I think at the end of the day though, I’m trying to get all the songs I’m working on to a general common place. I just want the feel to be right. I think our job is like polishing a diamond. At the end of it all you want the listener to be say, “Wow”. Whether it’s a crazy 808 that’s shaking your car mirror of the windshield or just evoking a certain feeling.

With (Morgan Heritage), we actually started working together because they came in to my room during a mix session. They were like, “We were next door and the walls were coming down! We gotta meet this guy!” (laughs) I love their music, and I love them even more as people, they’re really good guys. The second we worked together the chemistry was there, I understood their music, they understood me. Working on that Strictly Roots record was just all love.

Would you say the rules of mixing for hip hop and urban are changing? The music itself seems to be evolving so quickly, and in so many fascinating directions. What are you hearing? Either for mixing it, or just the sound?

Music reflects society and mixing reflects technology. For example, if you were back in the mid ‘90’s, no kid can just walk into a room and start mixing, toying around, or learning. It was a very hard business to break into.

Today, we’re in a world where you open up a laptop and you get Pro Tools HD, and maybe an Apollo interface and it’s insane the quality that you can achieve.

I think what’s happening is more hands are involved now, so although the technology’s changing the sound in a technical way, the amount of people that are now able to play around and explore are changing the rules. You get a kid who doesn’t have ten years under their belt, or GRAMMYs and plaques, but happens to have mixed a hit record.

Suddenly, the next client is like, “I want my song to sound like this.” So although this kid probably made some mistakes and maybe didn’t necessarily mix the song the right, it doesn’t matter because, his mistake now becomes a thing. I think technology has had a huge impact on who can participate and in turn what mixes sound like today. It’s changing at a crazy pace and I love it!

Lu’s Tips for the Next Generation of Mixers

What’s your advice to young mix engineers who want to have success on your level? How can they improve their mixes, and what should they know about as people too, that maybe has nothing to do with mixing?

I’m glad you posed the question that way, because to me, other than the obvious learning and working on your craft and regardless of the fact that it’s more accessible, it’s not easier because it’s more accessible. In other words you still need to work on your ears and put the time into listening and discerning.

So the two biggest pieces of advice that I can give is, don’t get frustrated if you’re not hearing something. I hear people say it all the time, “I can’t hear compression,” and I was there once. Now, I wish I didn’t hear compression! (laughs) That’s just growth. Be patient with your ears and yourself, but put the flight hours in so that you do grow, so that you do pick up on things. There’s nothing better than listening!

The other thing I would say that’s really big, would be to be mindful of your confidence. What I mean by that is, when a mix work well, just make sure you remember that. Let it give you confidence to carry you to the next mix and ultimately to the next level. There’s so much self-doubt in this industry, it’s what we do. We are constantly second-guessing every move, its just the nature of mixing. What got me to the next level and sort of started that snowball effect, was when the client who I was working with felt my confidence, and felt comfortable because of it.

Clients are coming in for your expertise, and if you’re feeling like, “I’m learning on the job,” that’s fine, but you need to be a professional and project a confident vibe that makes your client feel that you are in charge. Now please down act like an arrogant asshole, that is the exact opposite of confident! (laughs)

The GRAMMY Awards just ended, and albums that you’ve mixed have won three GRAMMYs in prior years. What does that mean to you?

Don’t miss the sounds on the 2018 GRAMMY-nominated “Avrakedabra” by reggae masterminds Morgan Heritage.

If I’m not rooting for the records I worked on, I’d be lying! Obviously I want to keep going. This year again, Morgan Heritage was nominated for Avrakedabra which is the last record we did and an amazing album. I think I enjoyed that one even more than I did Strictly Roots.

It matters, and it doesn’t matter. I remember when I got my first GRAMMY nomination for “Who Let the Dogs Out.” It was exciting, and it was cool, but honestly I was so wrapped up with work that my mind wasn’t even on the GRAMMYs. When they won I was actually in a session in Miami and had no idea. People always say to me “You must go to all these record release parties and awards shows,” and I’m like, “I actually don’t.” I finish a project, and by the time the record is out and mastered and its record release party time, I’m already on another project. So to me, It’s a good thing to sort of not let your goals become the plaques and the accolades.

Now there’s something to be said about stopping and smelling the roses along the way. My wife stopped me one day and said to me, “You really should pause, look around and enjoy the fact that you have all this success,” and she’s right. It is very important, because some of these awards are the highest accolades you can receive. But it’s a balance and It’s only going to come if you are truly doing great work, and you’re focusing on that.

If you’re always at the party, then you’re not always in the studio. Know what I’m saying?

Lu, this has been great. Is there anything else we haven’t covered that you want SonicScoop readers to know?

Thanks David I enjoyed it as well. I’ll leave your readers with this. A lot of young engineers ask me, “What’s your setup?” I tell them all about my different setups and try to convey to them that I really don’t have any secrets.

In this business, it truly is the operator and not the machine. It’s really who you are, because all those micro decisions you’re making while mixing are what matters. A lot of times young guys are like, “If I had the money and I had this and that…” I’m like, “I’ve seen guys do it on an MBox.” It’s just who you are. Your dedication, work ethic and focus.

- David Weiss

Please note: When you buy products through links on this page, we may earn an affiliate commission.