Give the Mix a Roadmap: The Art of Keeping a Listener’s Interest

This is a guest post by Wessel Oltheten, a producer, engineer and author of the new book Mixing with Impact.

It’s not enough to simply grab listeners’ attention. You also have to keep them interested by managing their attention through time.

Last week, we looked at how to use some of the most powerful attention mechanisms to help attract a listener’s attention, and then focus it on the most important elements of your mix.

This week, we’ll go a little deeper to look at a few strategies for keeping a listener’s interest throughout an entire track, by providing them with a subconscious “roadmap” through your mix.

Attention Roadmaps

It’s useful to have a large-scale map of the entire world, but relying on it to get around town would be difficult, to say the least. This same idea holds true in reverse as well.

Similarly, listeners are capable of many different levels of focus, and some of them may have different preferences for how “zoomed in” or “zoomed out” they prefer to be when they are engaged with music. That preference may even change for each of us depending on the situation.

Fortunately, when a production is well-executed, even the most complex music can work on several levels at once.

A great mix can sound accessible and evocative enough at first listen to interest new listeners who may not be paying close attention to all of the intricate details just yet.

Only once you dive in deeper into this kind of mix, will you discover how you’re being played by all the subtle rhythmic and tonal changes. You might soon start to notice and enjoy the parallel structures that exist within it, and when they become overbearing, you can always zoom back out and revert to focusing on the main structure, and enjoying the overall “pull” of the song.

For me, this describes an optimal musical experience: First I’m taken away by the music. Then, once the music has won me over, I start to feel so at home with it, and I can explore more deeply and discover all of its hidden gems.

Creating such a complex experience requires knowing some tricks that will help you with real-time direction of the listener’s attention (as described in my last post). Preferably, this kind of guidance will not come in the form of sheet music, captions, or a voiceover telling you what’s important at any given time! The music should speak for itself. It’s your job to help make that happen by positioning its components in a way that makes their purposes clear. And in complex mixes, it can be useful to shift these positions over time.

Just like in a complex movie with twenty characters and four story lines, where a director might use specific imagery to clarify your place in time and the relationships between characters, you can use tonal-shaping and positioning of sounds within the soundscape to provide clarification to an arrangement. And, just like in a good movie, those relationships don’t always have to be the same in the end as they were in the beginning.

Granted, in music, there’s usually not a concrete storyline like there is in a movie. But there are often all kinds of patterns that combine to form a coherent structure.

If you can make this structure comprehensible, you’re allowing a listener to find her own way through the music—and eventually, come to enjoy all it’s substructures and patterns—without losing track of her place in the piece.

This very much resembles the job description of an orchestra conductor: While respecting the intent of the composer, the mixer helps determine where, and at what time, emphasis should be placed within a complex whole.

Shifting Focus Through Time

The author, Wessel Oltheten at work in his studio. His new book Mixing with Impact, is out now.

Some compositions lend themselves to being built up piece-by-piece. Others may tend to get boring with such a simple and straightforward approach—as if they reveal all their secrets to clearly and too readily.

In the latter case, where you may need to introduce many or all of the puzzle pieces at once, you can still create a sense of progression and development by focusing the listener’s attention on different components at different times.

For instance, if you mix the first chorus of a song in so that the three “main” components clearly draw the most attention, you can allow a focus shift to secondary elements in the second or third chorus.

While all the secondary elements were subconsciously present in the first chorus, you are now allowing them to be recognized more consciously, so that they can add an extra layer of interest as time goes on.

With this approach, there’s less risk of the overall structure beginning to feel too complex or cluttered, since you unmistakably introduced the section’s backbone thoroughly in the first chorus. The primary elements are now accepted as a given, and a listener requires less reinforcement or conscious attention to keep track of them.

No one can hear every single musical detail in a complex piece discreetly all at once. But by shifting attention to different layers through time by using balance, positioning and tonal coloration, you can help a listener grasp all the components of a complex structure over time.

I look at music production as an extension of the composition in this way. If a composition is simple or develops very gradually, it needs less ”explanation” in the form of dynamic mixing. But, when a composition is very complex, part of a mixer’s job is creating a clear distribution of attention between its different components.

Contrary to many beginners’ assumptions, this does not mean trying to make everything equally clear all once. (When everything is important, nothing is.) What is means is helping to guide a listener’s attention over time. This can help a listener to better grasp the concept of the composition immediately, and start enjoying it more deeply as it unfolds.

In these cases, the mixer is the most like a conductor: It is your job to determine the amount of attention each element should attract at a particular moment in time. Should it be elements of individual significance, like a leading melody? Or should attention be drawn to elements that are grouped together with other sounds, like four voices that form a chord you hear as one musical element?

This kind of role division can change constantly, which is why mixing—and conducting—is such a fun challenge.

Making Connections

A major and defining property of music is that it moves through time.

You have to be able to lock on to that movement in order to follow the musical events that occur along the ride. Providing a listener with this kind of ”tempo locking” requires a perceivable pulse.

Dance music tends to be very clear about its pulse: A four-on-the-floor kick drum is not to be missed. But when the rhythm becomes more complex, when the pulse isn’t being played as obviously, when it is merely implied, or when it is heard only in the interplay between various instruments, it’s worth paying special attention to how you present that pulse to a listener, and perhaps enhance it.

The other day, I heard an interesting groove that appeared to start out in 6/8 time, but those elements later turned out to be triplets in 4/4 time!

Within the groove, the competing patterns in 6/8 and 4/4 then became intertwined, which worked well only because different parts of the mix featured an emphasis on different elements. As a listener, I could enjoy how my attention shifted to the different subdivisions of the main pulse, while still keeping a strong sense of time and motion.

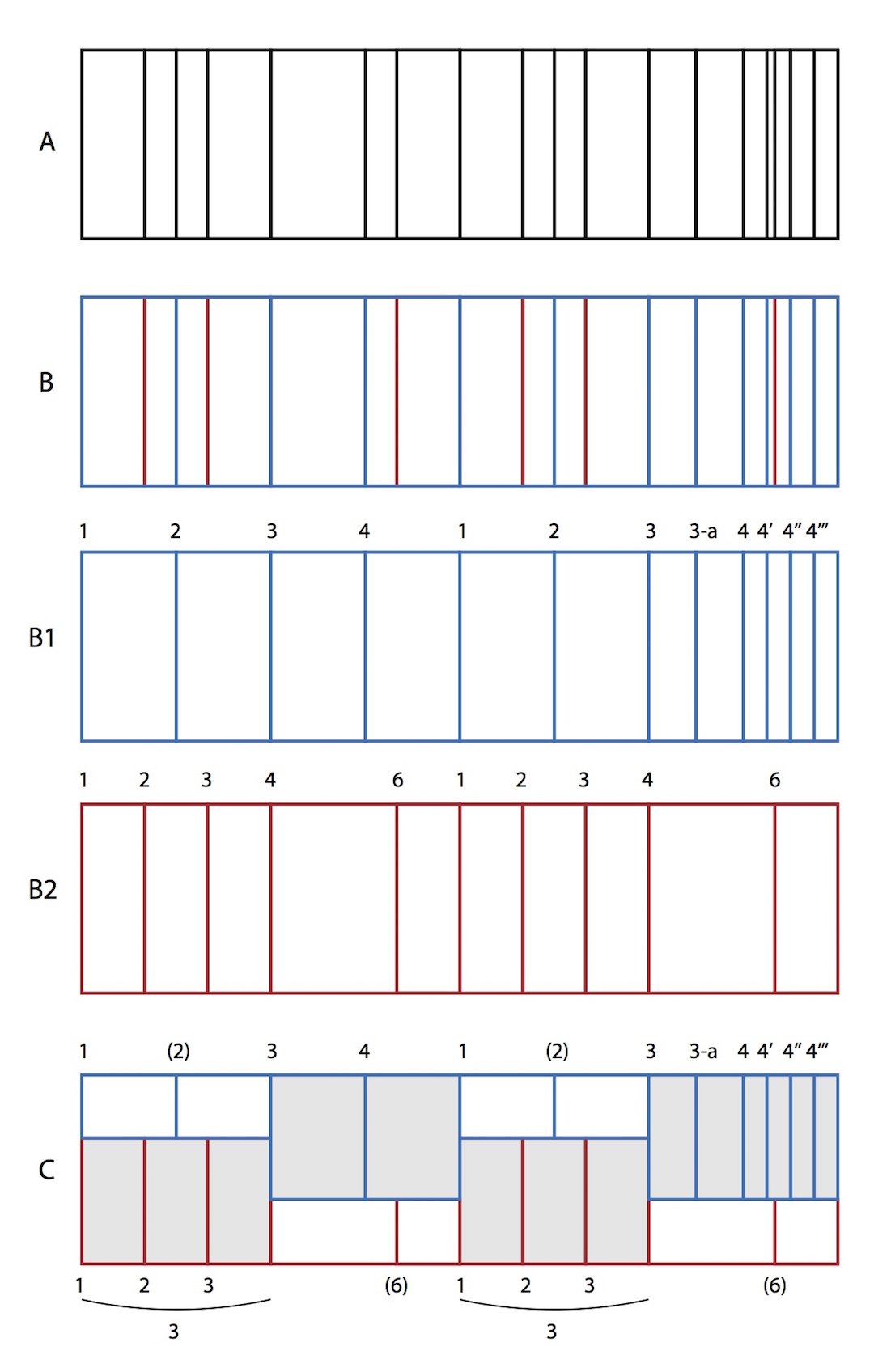

Since you can’t really count to four and six at the same time, it was the way the groove was mixed that told me when to think in fours and when to think in sixes, while in fact they were continuously happening at the same time. (See figure 13). This prevented conflict in the mix. There was always a clear division between the main and supporting parts of the groove.

This makes for a much more powerful statement than when you would mix the different time divisions to be equally present at all times, That approach could lead to something much more ambiguous, leaving it totally up to the listener to switch to thinking in fours or sixes at any given time. (Of course this approach is fine if ambiguity is what you’re after).

Figure 13: In rhythmic pattern (A) it’s hard to find the repeating patterns.

But by either isolating your subdivisions (B1 and B2), or by alternately highlighting each of the subdivisions, you can help a listener discover the underlying rhythmic organization.

This type of clarification can help make complex music more accessible to an audience, without oversimplifying it.

When mixing, one of my main activities is organizing the material. Not in the visual sense of lining up all the guitars on consecutive tracks, but in the sense of finding pieces of the puzzle that share a connection, and finding ways to link them together.

For instance, an arrangement can be crafted in such a way that a particular theme is divided up between the various instruments, so it appears in different forms throughout the piece. When I recognize a construction like that, I’ll often try to clarify it further in the mix, making it easier for a casual listener to appreciate the theme returning in all of its various forms.

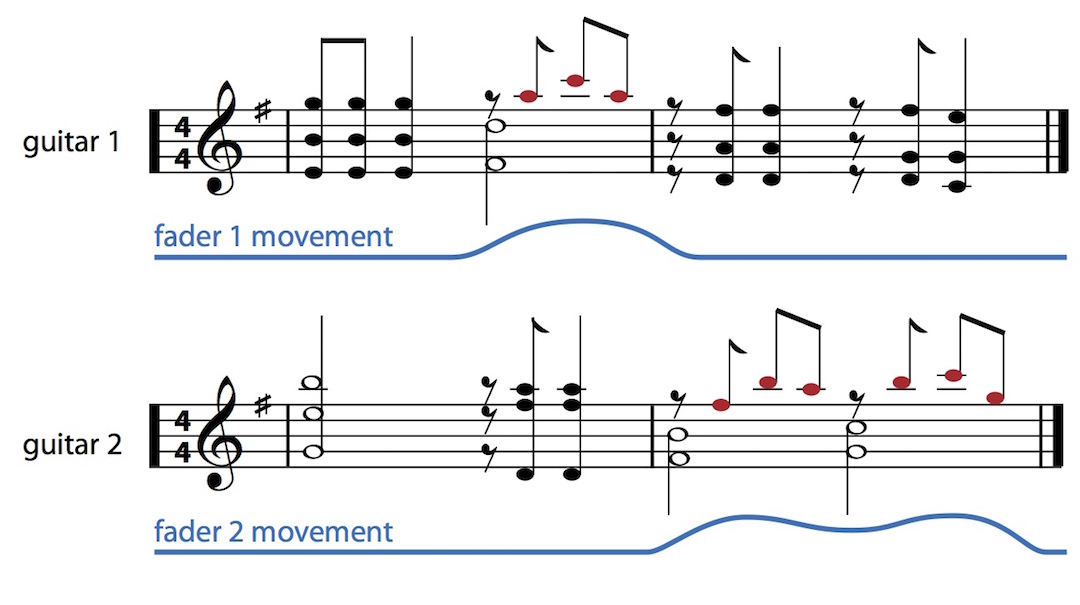

The approach can be as simple as slightly turning up a melodic section that is part of an overarching thematic structure (see figure 14).

Turning something up will make it stick out, and when a specific part played by different instruments all stick out, you’re more likely to connect them perceptually. There other approaches to make these kinds of connections as well: Reverbs or filters with a strong character, for instance, can also bring elements together.

Sometimes, it’s not the similarities but the differences between parts you want to clarify. In a call-and-response relationship between parts, for instance, you could color the parts in a distinctively different way, so that even when the response starts before the call has ended, you can still differentiate between the parts.

Figure 14: You could just make a static balance for these two guitar parts and be done with it. But if you look at their contents, there’s a connection to be made, highlighted here in red.

By automating the faders (represented here with blue curves), you can connect these melodic bits so they become more strongly identifiable as an overarching melodic pattern.

Contextual Awareness

The specific context that a piece of music is intended to be heard in, whether that’s pop radio, a YouTube video, a concert hall or a warehouse rave, should affect the way you distribute attention throughout a mix.

Personally, I struggle to work on minimalistic techno in the studio because I find it hard to envision what the experience will be like in a club at 4am. Out on the dance floor, the tension arcs that seem needlessly long and boring in a studio environment can work like a charm. I know many producers who for that reason ”test drive” their material in a DJ set, make notes, and take it back to the studio for adjusting.

Similar challenges come along with creating music that’s meant to be part of another experience, like a movie or a video game. It makes sense to judge your music in the context it is meant to serve, otherwise, making the call about how much attention your music can attract without complicating the overall experience can be very difficult.

The context of genre is also important. if you haven’t internalized the ”stylistic baggage” of a jazz aficionado, you’re more likely to present a jazz piece in an overly simplistic manner. For instance, by placing more emphasis on the kick drum, you may be giving an inexperienced jazz listener more structure to hold on to, but that loud kick will make the music seem flat and boring to a conventional jazz audience.

More often that not, music that exhibits multiple layers of attention, where the top one is more simplistic and the lower ones increase in complexity, tends to work well for many listeners and in many contexts. Such music can offer room to discover new things when you want to, but isn’t cognitively demanding if you’re not in the mood to dig deeper at the moment.

How Thick Should Your Boundary Lines Be?

I once received feedback on a mix from a client who told me that it was too easy to tell all the instruments apart. While perhaps an “achievement” in a sense, musically, this turned out to be much less powerful than if I had crafted a mix that spoke more to the imagination by keeping some things hidden just below its surface.

Since then, I’ve learned that attention is always limited in quantity. Neuroscientists have discovered that humans can’t truly “multitask”, which means they can’t consciously focus their attention on multiple concepts at once. Rather, when such demands are placed on us, we successively deal with the different tasks, by constantly shifting our focus and temporarily ”parking” other tasks or focal points in the background.

This process of “focus switching” has its limits. When you have to deal with a lot of information in a short time, some of it can get lost in the shuffle. This is especially the case when the information is constantly changing, like in music or a movie. You can’t always just rewind what you heard and start over. Oftentimes, when you miss crucial information you can lose the plot.

As the designer of a musical experience, you have to be aware of how many new elements that break expectations and demand individual attention are introduced at once. In my own experience, I tend to lose the plot when there are more than two or three of these new elements that require conscious processing at once. I get focused on figuring out the meaning of all the new stuff and forget about keeping track of the overall meaning.

It is possible to help listeners get used to unexpected elements and learn new structures, especially if you focus on making them less demanding of conscious attention and easier to keep track of. Therefore, I try to present a production in such a way that its sidetracks and deeper layers can be spotted, but so that they are not overly inviting of being consciously follow at first. I want listeners to first learn the main structure of a piece. Once that’s embedded and they start to feel free to look for new things, they’ll soon discover entry points to the deeper layers.

The added benefit to this approach—which is basically to establish a clear hierarchy in the amount of attention that each element attract—is that it almost automatically leads to mixes that have a lot of perspective and depth to them.

A mix with a deep and developing perspective like this has an alluring quality. It invites a listener to explore a world in which hidden details can be found, in contrast to a mix that immediately hands you all it has to offer at once.

Be Aware of Your Blind Spots

Judging how much attention a particular element attracts is very hard to do when you’ve heard that element many times. When you know your creation inside out, you can start missing things that other listeners will immediately notice, or you can start hearing things that many of them never will, simply because you’ve learned where they are hiding.

This is partly because, as a music creator, you tend to listen to your music in an analytic way. You’re too overly focused on the music’s inner workings.

When I think about this dynamic, I’m reminded of a now well-known psychology experiment that gives participants the assignment of counting how many times a basketball changes hands between players on a screen. Because this task takes up much of your attention, the average viewer doesn’t notice when a guy in a gorilla suit starts walking across the screen, and stops to beat his chest.

A viewer who is not working on the counting task spots the gorilla instantly, just like a casual listener is immediately aware that the vocals are too low in your mix. Therefore, it can’t hurt to change your focus once in a while and and find ways to listen less consciously.

One good way to do this is to distract yourself with other tasks. The brain is then forced to divide up the available attention, making it harder to dive as deep into the music as you usually do.

Freedom of Attention

What you focus on when you listen to a piece of music may be the instruments that are creating the sounds you hear, the melodies, rhythms, and chords they form, or even the meanings that these sounds and musical shapes have attached to them.

A phrase that hints at traditional forms of Indian music for instance, can subconsciously give a Western listener an exotic feeling, and make you think of anything (even non musical things) that you can connect to that kind of sound in your associative memory.

This is part of what makes music such a rich art form: It can have many layers not only physically, but imaginatively.

In order to use their associative memory—to fantasize, interpret, and ultimately, to attach new meaning to a piece of music—a listener must experience a sense of freedom. Their mind should be able to wander. That’s easy to lose track of if you don’t allow yourself to experience this ”imaginative layer” while you’re working on your own productions, because you’re too busy listening to it in analytical mode.

An analytical approach can make it deceptively appealing to keep on adding extra components. It keeps things interesting for you as a creator. But an average listener will probably not enjoy the information-packed production that results, which can seem pushy and overwhelming.

The Journey is the Destination

It’s good to realize that attention cannot be truly “controlled” in an absolute sense.

Every listener will experience your work differently. Their personal background, mood, listening circumstances, and much more, will make them sure to find their own way. They’ll attribute meaning to your music that you would have never thought of, and resisting their interpretation is pointless.

Like the frustrated songwriter yelling at the bar crowd to be quiet when he sings his new songs, it’s just no use trying to force audience attention, or a particular way of experiencing music. It has to speak for itself.

What you can do to increase the odds of listeners embracing your music, is to design something of an “attention roadmap” that helps new listeners find their way through the music and to enjoy themselves, while offering the option for more experienced listeners to dive in deeper.

Once in a while, it helps to ground things in your music. Return to familiar territory now and then, and allow listeners that took a sidetrack to tune back in once again. Playing the old sing-a-long in that noisy bar isn’t such a bad idea. It may well refocus attention on the stage, allowing the next song to get noticed. You can apply the same kind of thinking to your compositions, and your mixes.

Wessel Oltheten is a producer and engineer who lives and works in the Netherlands. He is the author of the new book Mixing with Impact.

For more great insights into both mixing and mastering, try our full-length courses with SonicScoop editor Justin Colletti, Mixing Breakthroughs and Mastering Demystified.

Please note: When you buy products through links on this page, we may earn an affiliate commission.