Can an Artist Remix and Remaster Their Own Album? Blake Morgan Makes His Case

If you had the power to go back in time, what would you change?

Ask a music artist, producer, mixer, or mastering engineer that question, and you know exactly what the answer would be: They’d return to the studio and improve a treasured song from their past catalog. Whether it’s one fader move or a melange of moments, a reinvention would get executed, transforming their sighs of regret into one of sonic triumph.

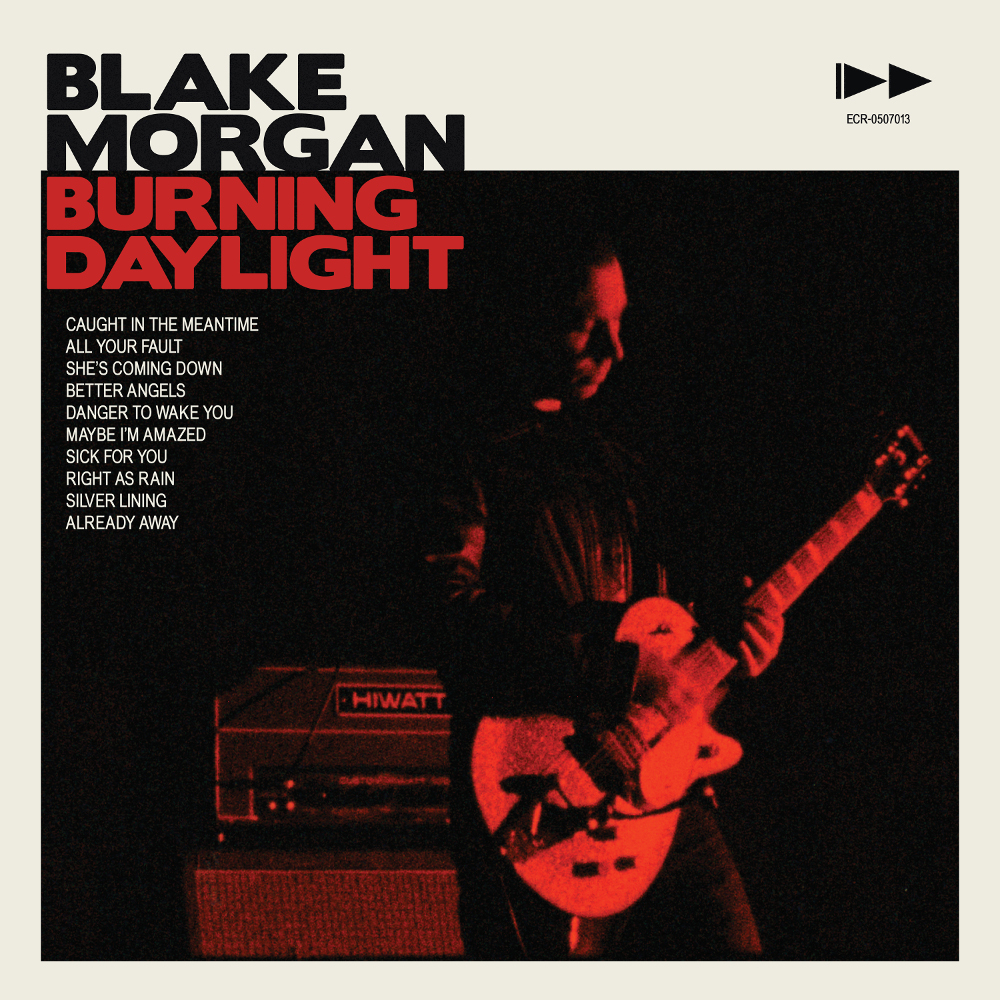

Turns out, music makers are starting to wake up to the fact that they can do just that. The prolific songwriter Blake Morgan didn’t have a TARDIS he could jump into for a new mix of his powerful 2005 album Burning Daylight, but he had something almost as excellent. In his possession were the record’s original digital multitracks, his to revisit as he pleased by dint of the fact that they were released on his own label, ECR Music Group.

ECR is a home not only to Morgan but a host of acclaimed artists including David Poe, Janita, Lesley Gore, Terry Manning, and Tracy Bonham. Converging a DIY ethic with the full support of global distribution via SONY/Orchard, a core attraction of ECR is all artists’ access to Morgan’s charismatic NYC studio. It’s an amenity that Morgan took full advantage of when the urge overwhelmed him to fully remix and remaster Burning Daylight.

Listening to the original release over the years, Morgan found himself asking himself the same question that countless producers query after the work is signed, sealed, and delivered: What could I have done better? While most creators re-experience their past works with regrets about any flaws and simply resolve to improve the next time around, Morgan’s ennui evolved into a different idea: Remix the album with the new tools available a decade-plus later, and hear his songs as he now envisioned them.

And there was no shortage of material for him to sink his wizened techniques into Burning Daylight, an organic album where precision arrangements of guitar, drums, keys, and vocal harmonies play out in emotionally charged fashion song after song. Complete with the opportunity for you to A/B the old and the new, you can hear for yourself how he put an evolved spin on tracks like the album’s beautifully emotional opener, “Caught in the Meantime,” the prowling rocker “All Your Fault”, and the longingly spare ballad that is “Better Angels”, an ongoing cliffhanger that keeps the listener locked in for the full 4:21 .

As you’ll see below in Morgan’s highly detailed accounting of the project, he acknowledges the hazards of his undertaking: “Under normal circumstances, an artist mixing and mastering their own work is dangerous.” But this was not a no-holds barred super-DJ blowout of Burning Daylight — there would be resolute rules attached.

Firm in his philosophy that “Producing is arranging,” Morgan asks extremely deep questions as he moves forward through this musical minefield of his own making. In the process, could he successfully transform Burning Daylight from 2005 Foo Fighters to Revolver? What did he radically alter in the mix? And how did the songs remain the same?

Prepare for a comprehensive clinic in micing, mixing, mastering and musical philosophy. And there are plugin tips galore, but this is no geek out — it’s the chronicles of a dedicated artisan fully explaining the use of his tools. The result of his labors is a complete refresh, 13 years later, that finally reflects a passionate artist’s original vision.

This Soundcloud players hosts the remixed/remastered versions of each song from “Burning Daylight”, followed by the original 2005 version for immediate comparison — exclusive to SonicScoop readers.

First, a backgrounder about the original 2005 recording, mix, and master of Burning Daylight, remixed and remastered for 2018 by Blake Morgan:

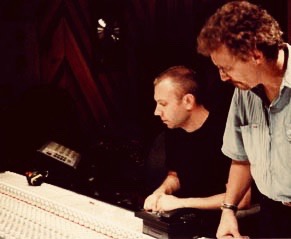

Burning Daylight is my second album, and was originally recorded and released in 2005. I co-produced it with Grammy Award-winning producer and engineer, Phil Nicolo (Urge Overkill, John Lennon, Bob Dylan, The Fugees, Lauryn Hill) at the legendary Studio 4 in Philadelphia.

To start, Phil and I tracked all the drums against guide vocal and guitar tracks, in Studio 4’s original “A” room. We recorded to 2-inch tape off a Neve 8048 board. We then exported those tracks as 24/44.1 files, so I could then track everything else in my Greenwich Village studio here in New York City.

Once tracking was completed, we then dumped all my digital tracks back to the 2-inch tape in order to mix (thus marrying them to the original analog drum tracks). We then mixed the record on an SSL 4000 E/G board, off the 2-inch tape, and printed to half-inch.

Phil also originally mastered the record at Studio 4, using a combination of Weiss and Oram analog gear.

Technical notes about the 2018 restoration––remixing and remastering in hi-def from the original multitracks:

The impetus for this whole undertaking was two things: First, my record label, ECR Music Group, secured a new worldwide distribution deal with SONY/Orchard. Second, I signed a new music publishing deal with Modern Works Music Publishing. Those two happy developments made me think, “Well if I was ever going to go back and look under the hood of my recorded catalog, now would be the time.”

So, the first rules I employed were: no retakes, no re-recording, no Auto-tune, no “sweetening,” no auto-tempo. No “George Lucas-ing” so to speak. None of that.

In truth, I started with the original digital multi-tracks of the record and remixed each song from the ground up. I think the result is a striking one. It feels much tighter and more focused, much more natural, and it — ironically — adheres more to its analog nature.

With this updated and restored mix, I now feel the songwriting is able to jump forward and into view better than ever. To be clear: this is how I always wanted the record to sound when I was first making it. This isn’t a departure from the original plan for Burning Daylight––quite the contrary––it’s a better implementation of the original one. It’s been wonderful to have Phil’s blessing to undertake this challenge. As I often say, he hasn’t taught me everything he knows, he’s just taught me almost everything I know.

I worked alone––almost in solitude––to accomplish this new mix and master. And, very much to my surprise, it was done 100% “in the box.” The entire thing was done in Logic Pro X, using––exclusively––Universal Audio hardware, and plugins. As an analog snob (and a proud one), I have to say I’m astonished at how great UA’s gear and array of plugins are––the painstaking detail needed for this project wouldn’t have been possible to achieve any other way. I’m not acting as a shill for UA, nor do I have an endorsement, I’m just telling it like it is: their stuff is off the hook.

The final mixes were printed at 24/96, and the final master was also done in Logic Pro X, using UA plugins, at the same bit rate.

What happens when an artist does their own remix/remaster, as opposed to an outside engineering team:

Under normal circumstances, an artist mixing and mastering their own work is dangerous. It’s usually a bad idea.

Objectivity is a valuable and rare commodity, and it’s crucial to possess it in order to make good (or great) art in the studio. However, there are a select few artists––Daniel Lanois, Jason Falkner, Jon Brion for example––for whom the circumstances are not normal. These are artists whose artistry doesn’t end at the performance, or at the writing. It extends through each artistic choice in the record-making process.

This is where their greatness is revealed, in my opinion––they can do it all. As I often say, “producing is arranging.” What compressor you use, and why, is a powerful arranging choice. Why plate reverb? Why not spring reverb? Why any reverb? Why an SSL channel strip and not an API? These are not simply “colors” that add something to a record––in my opinion, they are choices that define that record.

For better or for worse, I’ve always fashioned my own career following in the footsteps of the heroes I listed above (Lanois, Falkner, Brion). And the more I’ve learned, the deeper I’ve gone into the weeds of recording and mixing, the better my work has become. After having made 30 or so records, seeing a record all the way through, from pre-production to master, is the only way I’m interested in working. And that’s true when I’m producing/engineering other artists, as well as my own work.

The key is that objectivity: Can one maintain a grasp on reality in the studio, and not be swayed (fully) by the emotion of the moment?

Burning Daylight is the only album I’ve ever made where my own hands weren’t on the console during the mix, and I’ve always wanted them to be. So in my case, the artist-as-mix-engineer isn’t a departure from my norm, it’s actually a return to it. I’ve recorded, mixed, and mastered each of my own albums since Burning Daylight, and I think this one now fits better than ever in my catalog. The years that passed since I originally made it have turned out to be a boon, and in working on it again I found I had more objectivity about it than ever.

What I was listening for:

In this case, I had to listen to see if what I’d always wanted to hear in my head was even possible. Was what I wanted really there? In the actual multi-tracks? Or was the stuff I wanted to change too “baked in” to the multi-tracks themselves?

To my surprise, the raw tracks sounded pretty great––with a couple of notable exceptions. Mostly, it was the guitar sounds that needs the most help: they were too bright and too brittle. Much of the record had been tracked and mixed in a very “2005” sort of Foo-Fighters way––and that’s not really what I’d wanted. I’d wanted to make more of a latter-day Revolver (not that anyone can, but still!).

The drum sounds were great––they were just too roomy (they’d been recorded in an enormous drum room). So I knew I’d want to tighten them a bit. I ended up killing the hi-hat track, and the far room mic to accomplish this. The bass was maybe the best sounding element of all: it’s been tracked DI, through a Neve 1272, and then a SansAmp (an old Tchad Blake trick). Sounded great.

The guitars were too bright (by a lot), and the vocals had been a little too compressed in tracking, so I knew I’d need to work with them on the de-essing front, while rounding them EQ-wise in the mix. Once I’d identified these issues, I then got to work in fixing them. The key was that the “art” was indeed there. These songs –– and the tracks that made up the recordings –– did work, were valuable, and would be able to be restored.

What I changed, and left the same, the second time around:

From a mix standpoint, I changed almost everything. Seriously.

The only thing that stayed pretty much the same was the panning mapping. Generally, what was hard left or right stayed that way. If it had been on the left the first time around, it probably still is. Also, something I’ve learned from another mentor of mine, Terry Manning (Led Zeppelin, Shakira, Lenny Kravitz, ZZ Top), is that you’d better have a great reason to not pan something hard left or right, or dead center. There may be a reason, but it’d better be a great one.

I think if you looked at my mix sessions for the remix, the only thing you’d see not hard left or right are the drum overheads. I always track drums with a stereo pair of overheads, a close room mic, and a far room mic (room mics in mono, yes!). I love the way the trail of each hit fades naturally into the center of the stereo picture. Those overheads I usually pan at 3 and 9 o’clock instead of hard left or right. I find it gives the drums more cohesion, while leaving more room for guitars. I feel the whole mix feels wider that way, and more letterboxed. Other than that, it’s left, right, or center for just about everything.

What tools I had available this time that weren’t previusly available:

The two bedrock keys to this new mix for me were that I used the UA SSL 4000 E channel strip plugin on every channel of the mix, and I used the UA Studer A800 Multitrack Tape Recorder on every channel of the mix too with the exception of the drums — seeing as how they’d been tracked to 2-inch tape originally, I didn’t want to oversaturate them and risk losing too may transients).

The decision to build the mix off of those two plugins on every channel meant I was also using digital versions of tools that weren’t un-similar to what had been used the first time around (the record had originally been mixed off of 2-inch tape, on an SSL 4000 E/G board). This allowed me to have a great base for everything, and get musical and creative with the rest.

In addition to ease-of use, those two plugins are––without exaggeration––stunning. And again, I’m an analog-head, and it almost pains me to say how great they are. But they are. The SSL plugin really feels like the hardware––it’s got the upper-mid magic to it, as does the dynamics section, which feels exactly like the real thing to me. I think it’s indistinguishable from the hardware.

And the Studer A800 is glorious. I run it as follows: 30ips, +9, GP9. It’s the “highest fi” setting perhaps, so it doesn’t sound like an effect. Instead, it has a gorgeous low-end bump that really binds your tracks together. I don’t hit it too hard, just get that needle up to -3 db or maybe a little above that, but never hitting the red. Those two plugins together (Studer first, SLL second) on each channel and you’re ready to mix anything.

Across the mix bus, I had the UA SSL 4000 G Bus Compressor, and the Ampex ATR-102 Mastering Tape Recorder plugins. Not only is this what I want to hear on a mix, it’s also conveniently what was (basically) used on the original mix of the record. For the SSL Bus Compressor, I like to run it at 10:1, with the slowest possible attack and fastest release, while getting –– at maximum –– 3db of compression. In fact, most of the time the needle is barely moving, and at most it’s touching 2 to 3 db of compression. So it’s really just skimming the peaks and bringing them back to the pack. Most people like to run it at a much lower ratio where the whole mix lives in the gain reduction, but I prefer the approach I mention. Just touching it, just a little.

I feel as strongly about the Ampex ATR-102 as I do about the Studer A800––it just sounds like what I grew up hearing with the hardware. The ATR-102 is the perfect complement to the A800 (as it was in the old days), and I again use it at 30ips, +9, GP9. Here I let the needles go right to 0db. These two bus tools seem to lock the kids in the car beautifully, so to speak, and they give you a mix ready for mastering. In this particular case with this record, they also gave the record an old-school feel I really wanted it to have. Very hi-fi –– but distinguishably old-school.

I’d say the two other tools/plugins I used constantly in this remix were the Pultec EQP-1A passive equalizer, and the Fairchild 660. Hard to beat either of these. The Pultec I used to warm up all the guitars, and also give some hug to the kick drum and bass guitar. I was concerned that if I overused it, things would start to sound homogenous, but the reverse happened. They brought each track to life, and in the case of the guitars, solved the bright-and-brittle issue. For them I rolled off a little of the highs, and added a good amount around 100hz and below. Perfection.

The 660 was used for every vocal on every Beatle record after A Hard Day’s Night, and it was used on every vocal track on this mix too. Because the vocals had been a little too slammed in tracking, I just used it a touch, but it made all the difference. Time constant “1” is the magic number — although “5” is perfect for some situations too — with just 2 to 3 db of reduction, on the original calibration curve. The vocals jumped to life, filled out, and the harshness just melted away. The EMT 140 Classic Plate Reverbarator, and the EP-34 Tape Echo — in mono! — gave the vocals, and many other elements too, just the love they needed.

Again, I’m shocked that I could put together such a mix using only plugins––and only Universal Audio plugins––but the proof is in the pudding. It worked, and worked great.

Mix and mastering moves — deeper insights into the tools I used:

The Mix: I think the key to the whole mix I performed was how the SSL channel strip was set up, specifically. It’s where the “sound” of the mix comes from. It’s the “console.” It, married with the G Bus compressor makes this record “feel” like an SSL record, which is what I generally want to hear –– on this record, and on most of the records I mix.

What I do on the SSL channel strip is make sure the compressor is just touching the signal: if that first yellow light is getting lit half of the time, that’s all I want. No more than that. I set it at 4:1. I also want to make sure the expander, or the “Gate 1” setting if you need more, is doing its job, but no more than that. Get the floor noise out, but nothing more. Better to be a little on the open side than on the closed side.

Moving to the EQ section, I do something that might seem bizarre. I start by setting every track almost exactly the same. Bandwidth for each band at a Q of 1.5, with each band boosting about 3db, at 12k, 2.6k, 560hz, and 80hz. I know…that’s crazy, right? Well, not so much. What this approach does is give you that “console” sound, while bring out the differences in each source, not muddying them. Now, there are exceptions. For the kick drum I’ll suck out some 400hz and add more at 12k. For overheads and room mics I’ll bring down the low end. I’m not going to add 3db at 80hz for a tambourine. However, I’d say 70-80% of the tracks on the record will be set as I described above. From there, I’ll use the Pultec to sculpt further. The SSL channel strip is the meat-and-potatoes. The Pultec is the gravy. Same with the Fairchild. Gravy.

I like strong flavors, but not many of them. SSL, Pultec, Fairchild, EMT 140 Plate, EP-34 Tape Echo. The Studer A800 on every track. Every single delay you hear on the record is the EP-34. Every single reverberation on the record is the EMT 140, except for the snare, on which I used the Lexicon 224, just a touch, which made it pop. I think these kinds of broad strokes––used by an informed and intelligent engineer who has a vision about what she or he is after––makes a record sound like one. Big flavors, but only a few. Go big, or go home.

The Mastering: For this, I used three crucial plugins: The Manley Massive Passive Mastering EQ, the Manley Variable Mu Limiter Compressor, and the Sonnox Oxford Limiter v2, in that order.

The Massive Passive is really a Pultec on steroids. The key thing with it is that you don’t have to be scared of what you might think are big boosts. They look like they are, but they really aren’t. Use your ears, not your eyes. Because of all the warmth I’d added in the mix (especially all the low-end bump from the tape emulators), I knew I’d need to pull out a little 390hz, which I did (narrow Q).

From there, I generally added a little 47hz, and a db or 2 of 1.5k — Bob Ludwig once told me that he can count on two hands the number of records he’s mastered where he didn’t add a little at 1.8k. The high-end I added to taste, but again, because of the low bump and analog nature of the whole record, I added quite a bit at 12k and it seemed silky, and added some nice breath to the whole thing. No harshness at all.

The Vari-Mu is an elegant mastering compressor, with a powerful flavor all its own. I like to drive it just a bit (dual input up!), and I like the attack at 3 o’clock, and the release (recovery) at 12 o’clock. I use the “compress” setting for mastering and set the threshold so I’m getting––at most––1.5 to 2 db of compression. I like the HP side chain in, opening the door for 100hz and below, and I use it in stereo –– not the mid/side setting. A great tool.

The Oxford Limiter is a colorless and beautiful limiter perfect for the final step in mastering. I use an attack setting somewhere in the middle, with a fast release, and the soft knee off. Because all the heavy lifting was already done compression-wise (by the SSL G bus, the ATR-102, and the Vari-Mu), the Oxford is really just to accomplish some simple volume gain, and some technically important things: dithering at 24bit, and using the “Recon” meter Auto Comp to eliminate some inaudible peaks.

This is the best way to master if you’re working with strong mixes that don’t need too much “fixing,” in my opinion: you do a little here, a little there, while not putting too much weight on any one tool. If the Oxford is occasionally trimming a db or two at maximum, perfect. I’m really just polishing things up in mastering. I don’t ever (and neither do you) want to over-master. Having a Loudness meter in mastering is crucial. Now that the Loudness Wars are a thing of the past (thank God for that), I usually top out with the loudest parts of a track at around -8 LUFS. No need to squeeze more than that, and I try to do less if I can.

The very last step is that I do the final fades in mastering––not mixing––so that the completed master is what’s being faded, not the mixes pre-mastered. This is where I also make the decisions on the gaps between songs. It’s nice to have everything else done, and then get to this step. That way I can add or subtract time between, without affecting anything else.

When I have that step done and how I want it to sound, I know the record’s done. It’s the very, very last thing I do.

Looking back on the experience: A most rewarding rebirth

Honestly, I think this restoration is among the most rewarding experiences I’ve ever had working in music.

Those songs really matter to me and I think they’re reborn with this new mix. I feel a great mix should almost go unnoticed, the way a great film should be transparent. We don’t want to leave a movie saying, “Wow, that was so well made!” We want to leave a movie emotionally affected because of how it was made, whether our ribs hurt from laughing or our eyes are red from crying. We want to leave saying, “Oh my God can we go somewhere and talk about this?”

I think the depth and emotion in the songs on Burning Daylight has been unveiled. I really love believing in them again. For me, it’s like the windshield in front of the songs has been wiped clean with this mix, and they’ve been newly revealed.

DO attempt this yourself if you feel the urge — here’s why:

It’s always the right time to get it right––and if you’re an artist who is not 100% thrilled with an earlier record of yours, get it right if you can. If you have the skills and tools to do it yourself, fantastic. If you don’t but you have trusted people who can collaborate with you to get it done, that’s fantastic too.

“Difficulty” is something history never forgives. This was a very challenging mix to accomplish, but equally rewarding. And most rewarding is my knowledge as an artist that from this moment forward, this is the Burning Daylight people will hear. I didn’t “George Lucas” it, I didn’t change the writing, or the performances. I simply brought to life what I’d always wanted to hear. I decided to roll up my sleeves instead of wring my hands about it. I think any artist out there feeling the same should, and can, do the same.

— Blake Morgan is a songwriter, music producer, record label owner and unabashed activist for musician’s rights. Visit him at ECR Music Group.

Please note: When you buy products through links on this page, we may earn an affiliate commission.