Spatial Audio Mixing: A Platinum Producer’s Transformative Experience

What to do…when a song shocks you?

Inspiration that massive can motivate us to level up in the studio. That’s why the electronic dance music producer Latroit seized the chance to revisit a deeply heartfelt track with spatial mixing. The journey to becoming an immersive mixer proved transformational to him.

Learning spatial mixing techniques for Latroit.Charlz’ “Dance My Tears Away” proved to be remarkably intuitive. The Grammy-winning Latroit, a.k.a. Dennis White, used L-Acoustics L-ISA Studio to execute the mix. The result is atmospheric and spare, a classic palette of synths and vocals on a gliding music ride.

A disciple of Detroit techno, White’s career took off when he became music director for renowned innovator Kevin Saunderson’s multi-platinum electronic artist Inner City. He’s LA-based these days, making waves as a prolific producer, composer, and songwriter. Latroit’s Grammy win came in 2018 for “Best Remixed Recording (Non-Classical),” recognizing his remix of Depeche Mode’s “You Move”.

He’s jamming out on the West Coast now, but Latroit nonetheless hears broad creative influences in his Detroit upbringing.

“Every which way,” he confirms. “The cultural impact of the music out of Detroit the last five decades was as massive as it was diverse. We were culturally incubated in a city that spawned: the Motown Sound, proto punk with Iggy, the Stooges, MC5. Rock with Ted Nugent and Bob Seger. Funk from George Clinton/ Parliament Funkadelic. Detroit techno, particularly Kevin Saunderson and his group Inner City, gave the world two of its first electronic music dance crossover hits with ‘Big Fun’ and ‘Good Life’ in the late ‘80’s.

“The legendary Detroit radio personality and DJ ‘The Electrifying Mojo’ taught his listeners that anything good, regardless of the genre, can go together — Y’know…kind of like people,” he continues. “Musical styles on radio back then were cut largely down racial divides, and Mojo broke those barriers down on a nightly basis. That was huge. You’d hear R&B, Rock, Funk, Techno, Soul all in the same set…which was not commonly done back then. And the weather. It’s shit for just enough of the year that one might be more inclined to stay in the basement working on music than going outdoors.”

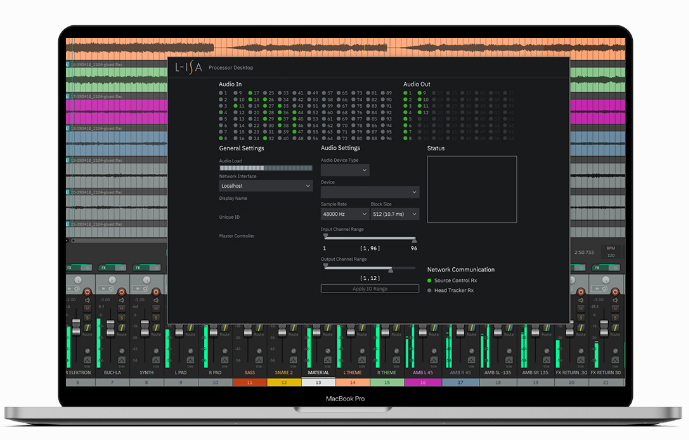

White executed the spatial mix for “Dance My Tears Away”, as well as the track “Someday” at L-Acoustics California HQ, working in their 18.1 spatial audio facility. He collaborated with L-Acoustics L-ISA engineer Carlos Mosquera, who guided Latroit on using L-ISA Studio, a personal studio-friendly software suite with L‑ISA 3D control interface and audio processing. Compatible with all major digital audio workstations (DAWs), L-ISA Studio enables spatial mixing on a personal Mac. Users can mix 3D audio with speakers or headphones, leveraging its binaural engine to produce natural, immersive 3D audio on headphones with head tracking, or up to 12 loudspeakers in any studio.

In this Q&A w/SonicScoop on what is spatial audio, Latroit discusses his learning curve for what works in spatial – and what doesn’t. He also instructs on how to think ahead to immersive mixing when you’re recording a track. Plus, what surprises happen in the frequency spectrum?

The multiplatinum producer follows it up with some Spatial Mixing 101 tips for first-timers. Hint: Crazy go nuts! He’ll also show you where stereo headphones fit in, if you don’t have an immersive speaker setup.

Tell us about your personal studio in LA. How is it set up to help you to execute on musical vision?

Nothing special, I’m afraid, other than to say that I’ve had the exact same studio setup, relative to where the desk, speakers, sound treatment, synths, guitars, outboard – everything – the identical set up in every home that I’ve lived in since 1995. I feel like that spatial familiarity has a positive impact on my creative output.

You won a Grammy in 2018 for your remix of Depeche Mode’s “You Move.” What has remixing taught you about the process of reimagining music?

I think that “remixing” is just a core part of my process, whether I’m working on a remix or an original that I’m creating from scratch. I tend to need something to deconstruct and work against as a part of my process. Rather than labor over finding the “right” sounds for a track, I’ll just throw the first random ideas that present themselves, and work against it later in the session. “Not this” is an easier decision for me to make than “What should this be?”

But when taking that approach, I have to be mindful not to miss potentially usable “accidents” simply because I’ve already decided that an idea is just a placeholder. So it’s really valuable to me to have a second set of ears in the room to help me identify the best bits of an idea in real time. My creative partner Annie (Pretty Garter) is very helpful in this regard.

You’re a relative newcomer to spatial audio. What got you interested in mixing for spatial audio?

My introduction to L-Acoustics, actually. My friend and colleague of many years, Jason Bentley, had been introduced to the company and asked if I’d be interested in doing “something” with them.

(l-r) L-Acoustics’ Carlos Mosquera, Latroit, and music supervisor Jason Bentley. (Photo credit: ZB Images)

Jason brought me in on the Depeche Mode remix project – good things happen for me when I follow his lead – so I joined him to meet the company at their North American headquarters in Westlake Village, and I was simply blown away by what they are doing there and how they are doing it. Everyone there is so smart, so talented, so switched on… whatever they were doing, I wanted to be doing with them.

I was instantly drawn to the L-ISA spatial mixing platform. It is so intuitive, simple, fun to use…I really appreciate the opportunity that they’ve given me to explore this space in their ecosystem.

How did you settle on your songs “Dance My Tears Away” and the new Armada Music release “Someday (Latroit Edition)” for your first spatial audio remix projects? Likewise, what should SonicScoop readers look for in their tracks to select a good candidate for experimenting with spatial audio mixing?

The instrumentation and production of both songs is Electronic-based, built on analog synthesis production with lush and ambient instrumentation. Those elements are particularly well suited to spatial mix experiments.

Why is that?

Because, unlike some other genres of music – let’s use “orchestral” as an example – there aren’t any preconceived notions as to where in the room an instrument should be. If you’re listening to an orchestral piece with a four-person cello section, it might be distracting to place those four cellos in four different speakers across the sphere of an 18.1 mix in a traditional orchestral recording – that said, it sounds like an interesting experiment for a modern piece!

But with a synth, you can play four different notes monophonically from the same synth patch and have them in four different place in the mix and it works. Who’s to say where in the mix synth parts should be? There is less precedent for that and a bit more room for experimentation, I think.

Latroit and Carlos Mosquera (seated) at L-Acoustics California-based immersive mixing facility. (Photo credit: ZB Images)

The Immersive Learning Curve

You collaborated on those mixes with L-Acoustics L-ISA engineer Carlos Mosquera at the L-Acoustics headquarters in California. What was the learning curve for using L-ISA to execute the mix?

Well…simply couldn’t have happened without Carlos’ technical expertise and musical instincts. He did a great job of mentoring me through that process. Patiently letting me experiment with newbie ideas that he surely knew weren’t going to work.

There is quite a bit of discretion required in mixing in spatial for exactly that reason. There are so many possibilities, and I was quickly reminded that just because I could do something didn’t necessarily mean that I should be doing it.

As for the program itself, L-ISA really is a delight to work with. The graphic interface shows a visual representation of where sounds are in the 360 mix field, allowing you to effortlessly move sounds around, back, front, all very intuitively. L-ISA really makes mixing music fun. I found it not too far off from being a really fun iPad game, which I think is really important, obviously – let’s keep this stuff fun, you know? I really believe that people are more likely to have fun listening to something if you were having fun while you made it.

As the spatial mix unfolded, what were some of the surprises along the way? What worked well that you weren’t expecting? Conversely, what mix experiments turned out to not work as well as you were hoping?

An example of something that didn’t work: With the vocals for “Dance My Tears Away”, for instance, my “go-to” production move with Charlz’s vocals in a stereo mix is to stack three main vocal takes hard Left, Center, hard Right. That approach didn’t work at all in an 18.1 field, on their own, without the rest of the instrumentation mixed in the same speakers to glue them together. We ended up putting the three lead layers very close to each other in the center, and used reverb layers throughout the rest of the 360 field to create an environment for the tone of her voice to be heard.

Something that worked better than anticipated: I built “Dance My Tears Away” on some chordal tone poems that I constructed monophonically using the Dave Smith/ Toraiz AS-1 monophonic analog synth, one track at a time. The result was interesting in the stereo field but very compelling in surround – being able to put four notes from one chord using the same synth patch in four opposite points in an 18.1 field created a really lush sound. Really rich. I’m not sure that I’m doing a good job of explaining that technique, but I’ll surely employ it in every spatial mix that I do moving forward.

Something that I’ll be mindful of earlier in the production and recording process: More mics and mic placement techniques! For example – the piano in “Dance My Tears Away” was an intentionally lo-fi, mono bit of business, recorded with just one mic. Next time, I’ll record three additional room mics and place those around the mix.

These are great spatial mixing tips! What else did you pick up on?

Something that I’ll be more considerate of in future spatial mixes: What environment are we mixing for? For example, both spatial mixes were designed to be experienced in a home, or intimate environment. The experience that we were mixing for specifically was the L-Acoustics Creations project “The Island”, which is a fully immersive 18.1 sound space for homes.

Both tracks are dance-leaning electronic tracks and in these spatial mixes, the kick drum is confidently, and solely in the front of the mix field, which is appropriate for a more intimate, at-home type of environment. But in a nightclub or festival environment, the kick drum would have to be sonically represented in front and back positions in the mix and room. Any experienced club-goer would expect that.

Hervé Dejardin from Radio Paris is doing some remarkable work in live performance with spatial audio, particularly with the artist Molécule’s ‘Acousmatic 360’ shows and he had a lot of great insights relative to mixing for those types of environments that I look forward to exploring in L-ISA, particularly with some of the more Club orientated work that I have coming out with Armada Music.

How to Listen to Spatial Audio in Stereo Setups

Does the listener need to be listening to the spatial audio audio mix in a 7.1 environment to appreciate surround aspects of the mix? In other words, can aspects of the mix be appreciated on stereo headphones or stereo speakers?

Short answer: Yes, the attributes of a Dolby Atmos 7.1 “spatial audio” mix can be experienced in headphones. You can mix for Dolby Atmos in L-ISA in headphones, and you can enjoy the results as a listener in headphones. If you have Apple Music on an iPhone with the latest iOS 15.1, you can check it out for yourself right now.

Go to settings> music> Dolby Atmos> “Always On” (Click “ok” on the popup telling you that it doesn’t work on all speakers.)

Now open “Music.” Listen to “Rocket Man’’ by Elton John in headphones. In the middle of the chorus, go back to “Settings”> Music> Dolby Atmos> “Off.” if the mix was playing in “Spatial,” it will revert to stereo in one or two seconds, and you’ll hear the difference.

It won’t change your life, but I think that it does indeed sound better. A quick note to say that on a couple of occasions, the process of turning Dolby Atmos on and off in the settings for comparison seemed to cause the Dolby Atmos mixes to render incorrectly. They started to sound worse, but I attribute this to me messing around with the settings too much. It might be best to set it to “always on” and forget it.

Given time, spatial audio will become as standard a headphone listening experience as stereo has been since the ‘70’s. People won’t have to choose to listen to spatial mixes, it’ll just be what’s playing through their headphones.

Is it better? Well, in the voice of the great Nigel Tufnel, “It’s more space, innit?”

By the way, a quick acknowledgement that experts in spatial audio will be quick to point out that Apple’s appropriation of the term doesn’t quite satisfy the generally accepted definition of “spatial audio,” which is audio that can be heard in 3D, around you and above you. But it seems this is what we’re gonna be calling it now.

How would you characterize the experience of surround listening in stereo headphones?

A little explainer on why it’s possible to listen to a 7.1 Dolby Atmos mix in stereo headphones: Dolby Atmos is an “object-based” format. The other formats, “5.1,” “7.1,” “stereo,” and “quad,” are “channel based.”

In “Channel based” formats, a mix is committed to a specific number of channels, let’s say 7.1 for our purposes here. This 7.1 mix will only translate on a playback device that has the same amount of speakers as the channels count in the mix. A 7.1 channel based mix won’t work in the stereo field in headphones.

However In an “Object-Based” mixing format like L-ISA or Dolby Atmos, each recorded track is defined as an “object,” and placed in the 3D listening environment with metadata that is recorded on to the track, with sort of “xyz” coordinates telling the Atmos renderer — the thing that translates the mix information to the playback device — where in the 3D or 360 field to place the sound. This is based on the listener’s playback configuration, assigning the “object,” or track, to the nearest available speaker in that configuration.

That’s an important distinction.

Nerd note: Apple “supports” Dolby Atmos. It does not stream in Dolby Atmos. They appear to be using their own rendering technology to translate the Dolby Atmos file to a sort of Binaural file that they call “Headphone virtualization.” Spatial audio playback on Apple Music can be enjoyed on 3rd party headphones, but is particularly well suited to the Apple Airpod Max headphones. I tried both Bose QC35ii and the Airpod Max.

The middle ground between enjoying spatial audio on headphones, and having a full blown 7.1 speaker system, is a sound bar system. They aren’t true 7.1 but they add welcomed dimension to the listening experience, in my opinion.

Any last thoughts on the spatial listening experiences that are available to end users?

It’s worth mentioning that there are new technologies available that translate standard stereo signals to a surround audio listening experience, which simply must be heard to be believed.

Most notable the BACCH 3D sound technology, which can be heard on the “Jam Box” by Jawbone. I’ve heard it personally and its truly remarkable how it places sound around you from just a stereo signal. It’s like some kind of magic trick. No renderers, no nonsense, a quick and easy way to enjoy spatial audio without the fuss. Worth checking out.

Here are some helpful resources on the subject of spatial audio and audio technology: “Mixing in Dolby Atmos- How Does it Work?,” by Edgar Rothermich; History of stereo sound Wikipedia; L-ISA Immersive technology; and BACCH Labs.

The Spatial Mixing Mindset

How would you characterize the mindset that a mixer must take on when creating a spatial mix? How is that different from thinking in stereo?

One of the first things that Carlos showed me, and one of my favorite things about mixing spatially, is that you can leave the frequency spectrum of individual instruments much more intact than in stereo mixing.

Quick example: It’s common practice for mixers to roll off low frequencies from a piano or acoustic guitar track, in the context of a densely populated stereo recording, so that there is more room in the low end for the bass and kick and whatever else you want to fill that frequency range with. In an 18.1mix, you can simply assign the acoustic guitar with more of its low end frequencies intact to its own speaker… it doesn’t have to play nice with anything. And apply that to the whole mix – it sounds wonderful!

As I mentioned – considering the environment that your mix is most likely to be heard is important, relative to sound placement decisions.

There’s another creative possibility with mixing spatially that I learned from my friend Mark Mangini. He’s an Academy Award-winning sound designer who taught me a lot about telling stories and enhancing narratives with sound design and spatial mix choices.

For example, one could make mix choices that create a narrative of the vocalist in a song moving in and out of different types of environments, and at one point, you could apply that same sort of approach to placing the listener in different environments. Where do you want the listener to feel like they are? Outdoors? Indoors? On stage where the band is performing? In the crowd? From the perspective of the drummer playing the drums? This could go on all day…You can do a good bit of storytelling within spatial mixes.

I’d recommend going bananas with your first spatial mix: Overdo it and be ridiculous, like a kid running around a Chuck E. Cheese for the first time. Get to know a bit about how to do it by overdoing it, and then err on the side of discretion after that.

You got the opportunity to do this remix in L-Acoustics’ fully equipped 18.1 surround sound facility, L-ISA Immersive Hyperreal Sound. However, you told me that you believe a mixer/producer can have an equally productive experience working in headphones. Why is that?

Well, equally productive, but not quite equally fulfilling (laughs). Between the visual interface of L-ISA and a pair of good headphones you can get an effective approximation in headphones of what is happening with your mix in 360.

My experience was that I was able to get about 80% to 90% of a spatial mix done with L-ISA and at that point, you’d want to take it to a sound system. And nowadays, 7.1 systems don’t have to cost that much money, really.

How would you say that “Dance My Tears Away” & “Someday (Latroit Edition)” were transformed by their spatial mixes? What changed about the song’s aesthetic experience, and thereby its emotional impact?

I feel like both recordings became more about the song, instrumentation and vocals, becoming less “beat” focused, and I liked that. To me, listening to them in 7.1 adds a layer of emotion to the experience.

The stereo version is quite aggressive rhythmically, and that’s great for radio and playlists, but I feel that the spatial mixes elevate the recordings to much more enriching listening experiences.

You told me you feel that spatial mixing via the L-ISA platform is “transformational.” Why is that, and why do you feel artist/producer/mixers should investigate it? How do they take that first step?

Because of the ease of use, price-point, and technology. L-ISA enables all of us to work on spatial mixes right on our laptops or home/studio computers. You can get a pretty accurate spatial mix going in stereo headphones and a laptop in L-ISA.

Historically speaking, transformational things happen when powerful creative tools are made affordably available to a greater number of creators. Spatial audio is simply the next frontier of audio production, and it’s really exciting and invigorating to experience and be a part of. With regard to practical first steps to get into spatial audio as a mixer or producer:

- Speaking for myself, I’ll finish a mix in stereo. “Save-as” (call it “L-ISA bounce session”), and then bounce individual tracks out from the new session. I save a new session so that I can go into some of the tracks and return the low end that I may have carved out of some of the tracks for the stereo mix so that I have those frequencies available to me in the L-ISA mix environment.

- Download a trial license of L-ISA Here . To my knowledge, L-ISA works with most major DAWs.

- Watch the L-ISA ‘Quick Start’ videos here.

- Put on a set of headphones and start experimenting!

If you find that its right for you, it might make sense to make a modest investment in a 7.1 interface and speakers set up to get a full sense of it. Or maybe prior to that book some time at a studio with 7.1 for further exploration before diving in to buying gear.

— David Weiss is an Editor for SonicScoop.com, and has been covering pro audio developments for over 20 years. He is also the co-author of the music industry’s leading textbook on synch licensing, “Music Supervision, 2nd Edition: The Complete Guide to Selecting Music for Movies, TV, Games & New Media.” Email: david@sonicscoop.com

Please note: When you buy products through links on this page, we may earn an affiliate commission.