Advanced Drum Mixing: Time-Aligning Your Drum Tracks for Better Phase Coherence

When it comes to recording live musicians, few instruments are as misunderstood or mysterious as the drums.

The drum kit presents a complexity that just doesn’t exist when recording other instruments, simply because of the sheer number of components that make up even the most basic drum setup, as well as its wide frequency response and abundance of transients.

Even when you’re using a single microphone to record a full drum kit, there are still several drums and cymbals (not to mention the room) that need consideration and attention.

To try and maintain control over the balance of the drum kit, we recording engineers will often use multiple mics to allow us to manipulate the level and tone of each component while, hopefully, maintaining some sense of realism or believability.

But as you add more microphones, you also increase the likelihood of destructive interactions between the microphones, putting your whole sound at risk. These destructive interactions between mics are caused by phase cancellation.

The best way to combat phase cancellation is by placing your mics carefully to begin with. However, if you’re left with significant phase issues when it’s time to mix, a little bit of time-alignment can dramatically improve the clarity, coherence and impact of your drum sound. As you become more and more adept at this technique, you may even find that well-recorded drums can benefit from a little time spent experimenting with alignment.

To hear the sound of drums before and after time-alignment, listen below:

In just a few moments, we’ll look at a clear-step-by-step process for time aligning drums that works every time. But first, a little bit of background:

Phase Cancellation: The Arch Enemy of the Perfect Drum Sound

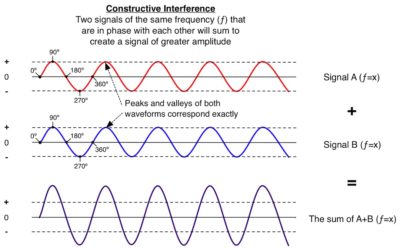

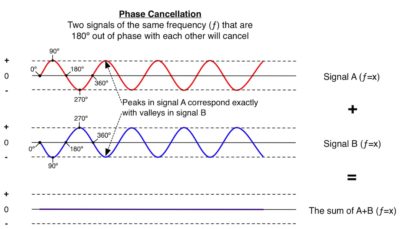

When you combine two signals of equal amplitude and frequency that are “in–phase” with one another, they will reinforce each other, and your signal will get louder as a result. This is known as “constructive interference“.

On the other hand, if you combine those same signals but they are 180˚ out of phase with each other they will cancel each other out completely. This is destructive interference or phase cancellation.

- Constructive interference enhances signals.

- Phase cancellation is a type of destructive interference. Perfect phase cancellation will silence a signal completely.

This basic concept is easy to understand by combining two sine waves of the same frequency and timing, or using two identical audio tracks. Simply open your DAW, take any audio file, and duplicate it so you have two copies. Then, invert the polarity on one track and bring up both faders to the same level. The combined output will be -∞, or rather, nothing.

This same idea is still at play when you are using multiple microphones on a full-frequency source like a drum kit, though becomes slightly more complicated. Not only are the signals more complex, but also there are multiple arrival times to deal with.

Multiple arrival times at each microphone can make phase coherence for multi-tracked a much more complicated affair.

Each mic on the kit will “hear” each drum and cymbal at a different level, at a different time, from a different angle, with a different frequency response. This creates multiple instances of constructive and destructive interference simultaneously.

The results can be unpredictable: Some frequencies will cancel completely while others will be slightly reduced; still others will be reinforced, and so on.

To make things even more confusing, the signals are not simply “in” or “out” of phase with each other: They can be out of phase by anywhere from 1˚-359˚, and by different amounts at different frequencies!

This is not a problem that can be easily fixed with just a polarity switch, either. Without the right techniques to deal with it, it can be a chaotic mess.

This kind of chaos is more common than you might expect, and less experienced recording engineers will often make matters worse by working on the sound of each mic individually without regard to how it will interact with the other mics as they are added to the drum mix.

For example, a new mixer might bring up the kick drum, make it sound good by itself, then solo the snare drum, make it sound good by itself, and so on and so on, down the line until each mic is “perfect”.

However, once you bring every fader back up and listen to the drum mix, there is shock and awe. (And not the good kind). This approach usually results in tracks that don’t fit together well, and when combined, the sound is nothing like the sum of its parts.

Drum tracks like this often suffer from uneven bass response, peaky midrange, a lack of high frequency detail, a hollow or non-existent center image in stereo, and a general absence of size and impact. These are not the adjectives you want to use when describing your work to prospective clients!

More experienced engineers will usually take a more comprehensive approach to working on a drum sound. They will pay attention to the overall balance, and show awareness of how the addition of each mic affects the balance and tone of the drum mix. They may still work on the sound of each mic, but only after the cumulative effects of all of the mics have been accounted for and dealt with through proper mic placement.

Better Phase Coherence = Less Work!

The most obvious benefit to ensuring that you have good phase coherence at the tracking stage is that your drum tracks end up needing less EQ and other processing to have impact and size, because everything is operating as a whole. It’s one drum sound, not just a bunch of drums combined (like you may get when using samples). The sound is more coherent, clear and focused, and yes, bigger.

Once the inter-mic relationships have been accounted for, it becomes far easier to manipulate the internal balance. For instance, a change in level of one mic won’t have a significant negative impact on the rest of the kit, and will instead just change the balance between elements. When everything is moving in the same direction, then each mic becomes mostly constructive rather than mostly destructive.

Tracks that are properly aligned will accept compression and EQ more seamlessly and with fewer surprises. But if your tracks aren’t well aligned, even careful use of compression and EQ can just make matters even worse.

Because compression affects the decay and sustain of a drum mic, the whole balance or tone of the kit can shift radically as the compressor changes the level of the sustain. The same goes with EQ: High frequency boosts cant reveal non-linear peaks and dips in the midrange or high frequencies as destructive phase interactions at these frequencies are increased or minimized.

While compression, EQ, reverb and distortion can all be effective at helping to maximize the size, impact and character of a drum sound, nothing will have a greater positive effect than having drum tracks that have good phase coherence. (Well, maybe having a good drummer and a good kit in a good room, but that’s another story.)

Just remember that “good phase coherence” doesn’t mean that everything is 100% “in phase”, because that’s essentially impossible with multi-mic techniques on a full drum kit. There are just too many varied arrival times and frequency response differences to bring everything completely in phase. These are complex, full-frequency signals at close proximity to each other, not simple sine waves. The best we can do is assure that destructive phase relationships are minimal, and that each new mic we fold in adds far more to the tone than it takes away.

How to Enhance Phase Coherence After Tracking

Ideally, all of this is taken care of in the tracking process by moving mics back and forth and flipping polarity switches. But what can be done if the drums were not tracked with such attention to detail?

DAWs have made it easier than ever to correct for these timing and phase problems after the fact in a way that was nearly impossible in the past.

I did speak to a famous mixer who told me that he used to “slide” tracks on analog tape by flipping the tape over, running the offending track through a digital delay, and then printing the newly-timed track to another track to correct for timing problems. But this was cumbersome at best.

Today, this procedure can be done quickly and easily, in real time, while listening to the effect, so you can make instant adjustments for maximum benefit. (And there’s no need to flip your computer over, either.)

By using the nudge feature in Pro Tools (all DAWs have this though it goes by different names in some) you can slip and slide your tracks into better timing and phase coherence with relative ease. I have found, however, that it’s best to have a plan and a procedure to perform this task or it can truly be a Pandora’s Box.

It is all too easy to do additional harm to your drum sound if you don’t apply some kind of precedence to some tracks over others. A move that may benefit the kick/snare relationship may ruin both the kick and snare’s relationship with the overheads. Once you consider that there may be 10, 12, 14 tracks of drums or more, you will quickly realize that there are plenty of chances to ruin the whole thing with the greatest of ease.

I have always done this procedure by ear, and I recommend that you do the same, preferably on a good pair of monitors or headphones that have a good, extended low frequency response.

Real Time Analyzers and spectrographs can’t always give you as clear of a picture as your ears can. Sometimes, the problems you’ll hear are easily seen on a spectrograph and other times, not so much, even though the issue is audibly obvious to you.

I don’t discourage using any tool available (including phase manipulation software or a phase meter) to locate and fix timing and phase issues, but ultimately, your moves will be based on your own judgment about what sounds “right”. Perhaps something that is causing audible phase cancellation will take care of a resonance that would be harder to control with EQ…you never know. Use your ears.

The Most Basic Adjustment: The Polarity Switch

The polarity switch, or “phase button”, as it is often inaccurately referred to, should be your first line of defense when trying to improve the phase coherence of your drum tracks. Simply reversing the polarity on one track when combining two or more will often indicate whether or not there’s a big problem or not. Sometimes, reversing the polarity on one track can completely eliminate or restore the majority of the low frequency content on a track. Consider yourself lucky if your problems are this obvious. When they are, the polarity button is an easy fix. Don’t be afraid to use it.

Sometimes however, the problems are not so cut and dried as a massive reduction in low frequency energy. The problem may be a bit more nebulous. To illustrate this, look at the following images to help visualize the interactions between two microphones in close proximity. (And right after I told you to “use your ears”.)

In most of these images, the kick and snare mics are both at the “0” position on the fader and the spectrogram is displaying their combined output through the mixer. There is no EQ or processing on either track.

Below, we are looking at a single kick drum hit, with both mics up. In the top graph, the kick drum and snare drum mics are both in their default polarity setting, and on the bottom graph the kick drum only has its polarity inverted.

There are noticeable differences between the two in the shape of the low frequency response, with more peaks and dips on the inverted polarity kick mic by itself. It looks a little peculiar and not very linear on its own. In this case, the normal polarity was dramatically better sounding. It was much fuller and had more impact and presence.

In the next image we are only looking at a single snare drum hit, with both mics active once again. We have the same situation as above, except that on the lower graph I inverted the polarity of the snare track only.

The differences here are not as visually obvious as they were on the kick drum. While the normal polarity version seems to have more low mid energy, it also suffers from many small dips between 700Hz and 2kHz. The inverted polarity track has flatter midrange but also has a pretty steep rolloff at 200Hz.

This is why it’s important to listen in order to make your judgment call. If I presented you with only visual evidence, there may not be an obvious choice. However, when you listen to the tracks in this case, you’d likely agree that the normal polarity tracks sounded better in both instances.

The thing to take away from this example is that there are some serious interactions between just two mics and these interactions affect each track differently. Knowing this, you can imagine how challenging it can be to get many mics to work together without too many negative interactions. This is where having the ability to shift tracks backward and forward in time can be an enormous boon.

But It Sure Looks Good

You should always build a rough mix when you start a mix, to acquaint yourself with what you’ve got. This will help you devise a direction in which to go.

When it comes to the drum mix, pay close attention to the way the drums fit or don’t fit together as you add more of the drum tracks to your rough mix. If the balance seems a bit fragile, where the addition of one or more tracks completely changes the tone, then you have likely have phase coherence issues, which you can work to minimize by following the simple process outlined later on.

On the other hand, even if nothing is glaringly wrong, then this same process will probably help you to enhance what’s good about it already, without dramatically altering the sound of the drums.

Well-recorded drums don’t usually need much help, and sometimes, don’t benefit much from changing the timing/phase relationships between tracks. It’s the poorly recorded drum tracks that will yield the most noticeable benefit. Regardless of what you have to work with, the time and effort are well worth it, so you I recommend you use this system each time and see it through to the end.

One might think that the best plan of action is to simply look at the waveforms and align them visually. While this is a solution in some cases, it does not always work and is not the best strategy. Many times, I am shocked at where tracks end up sounding their best, even though the front end of the waveforms are many dozens of samples apart.

Sometimes, absolute alignment fixes one problem (particularly with regards to imaging) but results in a change in frequency response or tone that is not as desirable, thus creating another problem.

For example: If you align the overhead mics to the snare mic, you may get something that looks and feels coherent, but now lacks the inherent and natural delay that exists between the snare and a mic that’s six or seven feet above it. This approach effectively eliminates the time element from the equation, which is a big reason to use multiple mics in the first place.

These time differences are what gives our ears its cues about depth and space, so eliminating them completely can make the drums seem smaller and more confined.

I prefer to start with the established relationships that are present and remain respectful to those differences, but then manipulate those relationships so that they sum together more effectively.

Once again, this is why I recommend using your ears as the final arbiter. The visuals are infinitely helpful and necessary to complete the process but ultimately, you should aim for what will achieve the sound you’re looking for. Even if it looks ugly.

Nudge, Nudge: Time to Move

We have to start somewhere, and for me, it’s with the kick and snare.

The kick and snare are the heart of the drum sound and are usually the most prominent drums in the mix, so it makes sense to give them the most attention.

Bringing the kick and snare up or down in the mix will typically have a profound effect on balance of the rest of the kit, so it’s wise to get them working together and in agreement with each other before muddying the waters with more tracks.

The basic process outlined below will not change as you add and align more tracks, but your focus will. How you apply this technique will depend on each additional track’s level in the whole drum mix and how much each track pushes or pulls the balance in or out of coherence.

Sometimes this determination is very obvious and easy to make, and other times you must simply make an arguable judgment call and sticking with it. You should always remember that as the mix gets more complicated, certain situations might cause you to reverse something you did earlier. This really doesn’t matter, as long as you end up with something that is big, exciting, and most importantly, coherent.

Remember that this is but one approach, and I encourage you to adapt it and find your own method that suits your style of working once you understand the process. For instance, if you build your drum sound based on the overheads or room mics primarily, then you can modify your approach to give those tracks priority. Adapt!

The Alignment Procedure:

Step 1: Listen to the kick mic by itself.

Step 2: Listen to the snare mic by itself.

Step 3: Bring both the kick and snare mics up to good relative levels but do no further processing.

Step 4: Reverse polarity on one track only and decide if this helps or hurts either or both drums. Leave it where it sounds best.

Step 5: Zoom in to view front end of each hit, Make note of which one is earlier relative to the other. (Look at the bleed from the other drums for time alignment reference).

Step 6: Set the nudge value to 10 samples

Step 7: While listening to the kick and snare, nudge the snare later in time (using the ‘+’ button in Pro Tools) by 10 samples and observe the changes as you do so. Try another 10 samples, and another.

Step 8: While nudging, listen for the point at which the snare gets fullest sounding and leave it there. You may have to go forward and backward to find this point.

Step 8A: If your snare gets thinner and thinner as you nudge, then find the point where its at its thinnest. Leave it there and invert the polarity on the snare mic.

Step 9: Make fine adjustments using a nudge value of 1 sample to see if you can further improve upon what you have. Otherwise, leave it where you left it at the end of Step 8.

Step 10: Mute the kick and snare and bring up the Left and Right overheads, and make any level and panning adjustments needed for them to sound as balanced as possible in stereo.

Step 11: Zoom in on the overhead waveforms and make a note of which one is earlier. Use a snare hit as an indicator since it is often the loudest thing in the overheads.

Step 12: Visually align the two overheads so the front end of a snare hit matches in both. (Be precise!).

Step 13: Listen to the overheads and hear whether the snare is solidly in the center of the stereo image. If it is, move on. If not, nudge one side forward and backward in one-sample increments until it is. Then, move on.

Step 14: Unmute the kick and snare and slowly fade in the overheads. Bring the overheads up to a level that gives you a good balance between drums, cymbals, and room ambience.

Step 15: Set the nudge value to 10 samples again.

Step 16: Select both overhead tracks so you can nudge them simultaneously without affecting their relative alignment. (Which you determined in step 12).

Step 17: While listening, nudge the overhead tracks forward by 10 sample increments. As before, take note of tone and character changes in the kick and snare. Nudge until the kick and snare sound their fullest and leave it there.

Step 17A: If you have a Little Labs IBP phase alignment tool or something similar, insert it on one of the overhead tracks and play around with the ‘phase’ adjustment while listening to the kick, snare and overheads. Sometimes you can make the kick and snare even fatter and make the image more solid. This is an optional step.

Step 18: Follow the same procedure as above with your room mics: Adjust their balances for a good center image in stereo, then nudge one until the kick and snare sound their fullest. I often nudge room mics by 100 samples at a time (which is still only about 7-10 ms!) to achieve the best sound possible. Your mileage may vary.

Step 19: Slowly fade in the high hat to an appropriate level and pan it as you prefer. Nudge the hi-hat in 10 sample increments until its location in the stereo image is precise and clear. Fine-tune with single sample adjustments if necessary.

Step 20: Bring up each tom individually to an appropriate level and pan it wherever you prefer. (Do not use EQ or gates yet). Nudge in 10 sample increments until the tom sounds fullest and has good low frequency response. Make sure there is no negative interaction between the toms and the kick or snare. Fine-tune with single-sample adjustments if necessary. Repeat for each subsequent tom.

Note: If there are multiple mics on a source, such as kick in and out, snare top and bottom, tom top and bottom, then work on each source on its own before adding it into the mix. Any time adjustments you make to that source from here should be global to that source, meaning you would nudge them as a “package”. For example:Time align the snare top and bottom to one another first, then select them both and then nudge them together.

What To Listen For When Reversing Polarity

Knowing and following the steps is easy enough. But developing an ear for what to do takes practice, and a bit more understanding.

For instance, when you push up the kick drum mic by itself and listen, the goal is simply to get a feel for the sound of the drum and think about what you like and don’t like about it. Don’t reach for the EQ or compressor just yet—that will come later, after you’ve already worked through the rest of the drums and brought them into alignment.

The same goes when you’re ready to hear the snare. The idea is to know what each sounds like on its own so you have a reference point about what aspect of the sound changes as you add them together.

When it comes time to combine these two mics and reverse one of them, this is where your judgement comes in.

But you first need to pay attention to the way the character of each drum is affected when you add the other to the mix: If the kick sounds fat and full by itself but gets thinner when you add the snare mic, then you have an obvious phase or polarity problem.

When this happens, the simple solution is to invert the polarity on one track or the other. Determining which one to invert may be influenced by other elements that are added later on (if for instance, the overheads need to be inverted to match the snare) but for now, you can pick one and move on.

(Note: It doesn’t really matter whether you choose to invert your kick and both your overheads or just invert your snare and leave the kick and overheads alone. In practice, however, I prefer to leave as many tracks in normal polarity just because it’s tidier and easier to keep track of. Certainly not because of anything scientific.)

What to Listen for While Nudging Your Close Mics

If there’s no obvious polarity issue, your next goal is to hear how the two tracks respond to manipulation in the time-domain. You will choose one of the tracks and nudge it a bit later in time, listening to both tracks while you nudge.

This is where the visuals become helpful and practically necessary. To determine which track you should be nudging, you must zoom in on the front end of the kick and snare waveforms to see which instrument’s bleed is earlier than the other. Whichever bleed shows up earlier will be nudged later so it ends up closer the other track’s location in time.

I think it’s better to do this than to move the later track earlier, simply because there will be many other time arrivals to deal with as you add more tracks to the mix and they are almost all going to be later than either the kick or the snare.

However, as you can see below, there is a bit of a problem with this basic logic: The kick and the snare almost never play at the same time (on this track at least) so you must use the bleed from one track into the other as your time alignment reference.

When the kick is playing, the kick bleed into the snare track (lower track) is slightly behind the kick hit by about 22 samples.

But when the snare is playing, the snare bleed into the kick track is behind by about 258 samples:

There is no way to make the hits and the bleed align perfectly in all cases, so you should just pick one and nudge the snare later in this case. While we know that the delay between them is 258 samples, I recommend that you still make your nudge adjustment purely by ear rather than starting with a nudge of 258 samples.

Your ear will give you the most pertinent information about what you’re trying to achieve, and your ear is attached directly to your brain—which happens to be the organ of choice when making determinations about your drum mix.

(Note: You could reject this logic and nudge the kick later, and it may work out! What seems obvious is not always the correct answer. There will be instances where you can abandon what seems logical for what sounds best to you.)

Once you know what mic you want to nudge (in this case, the snare) start nudging the snare later in time using the “+” in Pro Tools and listen to what happens.

I usually start with a slightly more coarse nudge value of 10 samples because the changes are more obvious and easier to hear. You can make fine adjustments of +/- 1 sample later on if you desire.

With both mics up and their faders at unity, start by nudging the snare later in time by 10 samples, then another 10 samples and so on and so on.

Pay close attention to how the tone and character of the kick and snare change with each increment. In almost every case, you will start to hear the snare get thicker or thinner. If it starts to get thicker sounding, then continue to increase the value until it starts to get thinner again. Then, back up by nudging backward (using the “-“ key) until you hear it getting thicker again.

It may take a few passes back and forth until you land on a spot that sounds fullest. This spot is where the coherence is greatest between the two tracks. You can then fine-tune this spot by nudging forward and backward by 1 sample at a time to see if you can improve what you have even further. You may or may not hear a difference from here. It really depends on the way the tracks were recorded.

In some instances, you may hear the snare get thinner and thinner as you nudge later and later instead. When this happens, you are starting to enter the realm where the polarity switch can help you out. In these cases, I nudge until I find a spot where the snare is at its thinnest (and thus, the most phase incoherent) and then I invert the polarity on the snare track. If you do this and the snare gets much fatter and fuller then you have again found the most coherent location for the track.

Through all of this, pay attention to how the sound of the kick drum changes as well. It’s rare, but there can be interactions between the kick and snare mic that will cause a low frequency reduction on the kick. When this happens, you will have to continue to nudge (in both directions) and invert the polarity until you find somewhere that is beneficial to both drums.

Once you’ve done this, it’s time to get started on the overheads.

What to Listen For When Working with the Overheads and Room Mics

This same process applies to overheads and room mics as well. I have always felt that the overheads are the one element that can make or break a drum sound, so these steps are supremely important here.

If you carefully nudge your overheads, it can even minimize the effect that poor close-mic’d sounds have on the health of the drum sound. Don’t pay attention to the number of samples and just focus on where they sound the best. I find I will usually end up moving them later than the kick and snare—which makes sense as they are further away—but in some rare circumstances, they end up a little earlier in time.

It’s all about finding the location where the phase discrepancies are more additive rather than subtractive. This not only increases the size of the drum sound but it also help with the impact, since everything is moving in the right direction together. That should be the goal!

The room mics require a little bit more “interpretation” on your part as the mixer. When the room sound is a big part of the drum sound, they may want to have them end up a bit closer in time to help give a more cohesive and unified feel. When the room mics are simply compressed to death and treated more as ambience (which is very common), you might be able to get away with something that is later in time. It really depends on your vision for the sound.

This the same process can be used for anything additional to the basic kit, including: effect or “dirty” mics, cowbells, auxiliary snares, cymbal mics, tympani, gong drums, other percussion, etc.

The idea is to work on the foundation of the kit and then account for the relative timing/phase of each element that is added to mix. Always keep your mind open to the idea inverting the polarity on any element at any time. I would argue that you should try this on anything you add, first, before you resort to nudging. The polarity switch can be powerful and revealing.

Finally, using a Little Labs IBP can be incredibly helpful but is also a bit of a can of worms. And if you don’t take the time to explore every option available (which can be time-consuming and may instill self-doubt at times) you may miss something remarkable.

Since not everyone has an IBP this is absolutely an optional step, and one reserved for the more experienced recording engineer. It’s a powerful tool, and like most powerful tools, it can be very destructive when misused.

Summing it Up

Once you’ve gone through this procedure, track by track, then you have accounted for practically any significant negative phase interactions between all of your drum tracks.

You should end up with a drum sound that is more solid, focused, and yes, more coherent, which doesn’t need as much EQ or processing as it would have otherwise

Over the years, I have found that this procedure helps to elevate somewhat mediocre drum sounds to a place that may not have been possible otherwise. (Outside of tracking them better in the first place.)

It’s important to note that some tracks will be in such good shape that they won’t see a huge benefit from going to this length of manipulation. In all my years of mixing other people’s tracks, however, I have never found an instance where I wasn’t able to improve the tracks by some measure.

The more you do this, the more intuitive you will be about how to get the most out of the procedure and how to go through it systematically and quickly. Your tracks and your clients will thank you. And you’ll be happier too, ending up with better tracks without having to resort to synthetic-sounding tricks or sample replacement to deliver an exciting, powerful, hard-hitting drum mix.

Mike Major is a Mixer/Producer/Recording and Mastering engineer from Dunedin, FL. He has worked with At The Drive-In, Coheed and Cambria, Sparta, Gone is Gone, As Tall as Lions, and hundreds of other artists over the last 30 years.

Major is the author of the book Recording Drums: The Complete Guide.

Please note: When you buy products through links on this page, we may earn an affiliate commission.

Eric Seaberg

February 2, 2017 at 10:29 pm (8 years ago)Without listening to the demos, I totally disagree. How many YEARS of classic hits have been recorded without the ability to shift digital files back-n-forth to match phase? Of course you know by changing the timing, you’re also changing ‘stereo’ imaging information?

I’ve been in the biz for 45-years, spending lots of time in LA, Hollywood and Burbank when labels had BUDGETS to record albums… if the technology had been available at the time, I can guarantee it never would’ve been used because the PERFORMANCE of the song always outweighed the TECHNOLOGICAL CORRECTNESS of the song… and that is what’s wrong with the music industry today. Everyone has forgotten about the performance and FEEL of the MUSIC.

As perfect as you think you can get the ‘digital imprint’ of a song, you’ll never be able to make it better if the performance sucks…

Mike Major

February 3, 2017 at 2:36 pm (8 years ago)I too have been in the music biz for a long time too (30 years) and started in the analog world where no such luxury was available. I always got it right with mic choice and positioning. There’s truly no substitute for that, I agree.

However, since I am often mixing tracks that people didn’t record in a studio with a veteran engineer I am often faced with a bunch of tracks that don’t fit together no matter what I do. This process helps correct, or at least minimize the deficiencies that occur when you have people recording drums who may be novices or who may not as careful or methodical as someone with experience.

And of course this changes the stereo imaging information-I talk about that and what to pay attention to when you’re making these adjustments. The fact of the matter is that adding more mics without regard to how they fit together will also change the stereo image (which happens too often). By being methodical about going through them (as you would when mixing any tracks) but knowing that you’re not stuck with the sometimes bad, destructive decisions related to the time-domain that people make when they put mics in bad places is nothing but beneficial to the mix.

Nowhere in the article do I suggest that this is a cure-all for a bad performance, bad musicians or a crummy song. I said nothing about the feel or the music. It’s merely a technique that I developed and use every day that makes the tracks fit together so the drum mix has more coherence. That’s all.

I also said nothing about technological correctness, either; I said that this makes the drums sound better. The technical descriptions are merely to give the reader some context about how and why to make the decisions instead of taking a stab in the dark.

I also said nothing about making things perfect. Just better.

And even when there’s a budget, sometimes the tracks don’t fit together.

George Piazza

February 4, 2017 at 1:51 pm (8 years ago)With the advent of smaller recording rooms, and subsequent decrease in budgets and big studios, for many, these techniques offers a way to improve drums sounds that are often unobtainable with the average modern recording setup. Though I agree somewhat with Eric Seaberg’s assessment, the fact is it is impractical to expect even seasoned recording / mixing engineers to get a great phase coherent multi mic drum recording in this age of limited budgets and time constraints. The other factor is that many older beloved drum recordings were done with minimal mic techniques, with excellent mics, preamps & drum-kits in finely tuned rooms. And those recordings are all over the map in terms of spectral content, stereo spread & definition.

For most working engineers, timing & phase adjustments are a fact of life in the contemporary recording / mixing world. And engineers have been checking polarity since it was an available option during recording and / or mixing. That is the very least a good mixing engineer should do when pulling together the drum sound on a recording.

Recording & mixing is an evolving art; drum replacement was already prevalent in the early 90’s. Today’s mixes generally demand more power, focus and stereo spread than recording of 20 + years ago. Though we could stand to back off on hyper-compression, bringing multi miked drum tracks into better coherence (without dumping all spatial cues) is a part of contemporary ‘good sound’.

Besides the Little Labs IBP, I would also recommend the Voxengo PHA979, a linear phase rotator & timing adjuster with a 1/3 octave FFT phase coherence spectrum display. It rotates all the frequencies by the same amount, unlike the minimum phase IBP.

Vic Steffens

February 4, 2017 at 11:24 pm (8 years ago)I’ve been in the business 48 years….I WIN!!!!!!!!. No seriously, I started as a live drummer, became a session drummer, transitioned to engineering and producing. Wa last years Producer f the Year in New England. Not that any of this bullshit matter…it just proves I’m old.

I have recorded a long list of great drummers successfully, from Steve Gadd to Mickey Curry, to Joe Franco..I got a list. With all do respect the concept of shifting drums around has always seemed ridiculous to me. I will grant you that in a mix situation you MIGHT be faced with something done so poorly you have no choice. Sure, any port in a storm. But of course in todays world you just use your drum replacement ax of choice. Once you go there…its a whole new ballgame….but I don’t think that is what we are talking about.

So why do I think this is nuts? First off….you are supposed to hear the kit as one instrument, not nine or ten. Reflections and time discrepancies are part of the sound of the kit. Those discrepancies generally make the kit sound fuller and bigger. Yes you can shift something and maybe make it sound better with another part of the kit, but that relationship you are changing is probably doing something not so good to another part of the kit.

So sure, you wanna play, have fun, but when you start writing articles that encourage it IMHOP a bunch of people that read this stuff will suddenly think that whatever crap you record can be magically saved in post. Someone will make a

drum saver” plug or something. Its not all that hard to do it right. Put your time into that.

Sorry to act like an old curmudgeon. Wait….I AM an old curmudgeon……

Mike Major

February 5, 2017 at 12:54 am (8 years ago)My Grandfather was 99 years old. He clearly wins.

If you listen to the examples above you can hear what I’m talking about in the article. The first example is not as dramatic but in the second one the snare is clearly fuller and more present and the overall sound has more impact. There are no other adjustments to the mix in the two examples; faders and panning are unchanged. In sample two it’s not a subtle difference. Seriously.

And the article pretty clearly states that this is something to do if things are not right when it comes time to mix.

Quote from the article:

The best way to combat phase cancellation is by placing your mics carefully to begin with. However, if you’re left with significant phase issues when it’s time to mix, a little bit of time-alignment can dramatically improve the clarity, coherence and impact of your drum sound.

I am not in any way implying that you can “magically save” anything with this technique. The idea is that you can improve the relationship between the mics. Sometimes significantly…other times, not so much. This is as close as you can get to moving mics around while you’re miking the drums. But since I’m talking about mixing tracks that have already been recorded, that is not an option.

When I did live sound years ago, we eventually used a digital crossover/drive system which, of course, gave us the ability to delay the PA system to match to stage sound and backline. Every time we did it, it sounded better and took less EQ because you weren’t fighting the differing arrival times and the inherent phase and EQ problems that they caused. I’ve simply applied the same concept to getting a bunch of drum mics to work together better.

This technique does make the drums sound more like one instrument since all the mics play together better. It also helps you to use less EQ and other crap to make the drums sound bigger and fuller, which is always better in my book. And the improvement may keep some from using samples at all. I rarely, if ever use samples because a) they’re evil, b) no matter how good they get, they just match the dynamics of the real thing, c) I am more interested in using something unique and original that came from the band, not a sample library.

The only way to avoid destructive phase problems when recording drums is to use one mic only, but most people don’t record that way and most contemporary drummers don’t want to hear their drums that way either.

The whole idea is to make the drums sound better, and usually, more like they did in the room.

Dietz Mix

February 6, 2017 at 7:27 am (8 years ago)Great advice! That’s one of the few examples where the WWW’s signal is indeed louder than its noise. 😉 Like Mike points out, time-alignment and phase-correction can make a good multi-mic recording great, and they can make mediocre ones usable (at least).

… one small objection has to be raised, though: Absolute phase _does_ matter. Especially in case of a really LF-rich kick drum a positive first half-wave will literally push the air out of the speakers (assuming that they are wired correctly). Flipping the phase of the kick (read: first half-wave negative) will “suck” the air away from the listener, thus reducing that sensation of a good “thump into the stomach” quite a bit.

What’s more, the phase relations between the kick drum and the bass (… the instrument, not the frequency range) will matter a lot, too. Keeping an eye on them will it make easier to create powerful, punchy mixes without lots of processing in the actual sense of the word.

PS: The all-important disclaimer: I’m in the mixing business since 30 years, and my grandfather would be around 120 by now. ;-D … and sorry for any strange neologisms – English is not my first language.

Mike Major

February 6, 2017 at 1:17 pm (8 years ago)Thanks Dietz Mix, I appreciate the kind words about the article.

You know, you say that English is not your first language, while using the word “neologisms” in the same sentence! I think you’re doing fine…

With regard to the absolute phase thing: I am speaking from my personal experience more than anything empirical, and simply put, I leave things where they sound best rather than seeing which direction the waveform or the speaker happens to be moving. I get your point though. A friend of mine used to wonder about this too: if the kick drum pushes air out of the front of the drum then the mic diaphragm will move inward (relative to itself, of course) which should then cause the speaker to move outward. It’s a strange relationship when considering what’s absolute phase, no?

I hear that some turtles live a very long life; sometimes 150 years. Imagine what they must know about recording!

Jesse Klapholz

March 15, 2017 at 2:59 pm (8 years ago)Check out Sound Radix’s Drum-Align, much easier to use than the Waves plugin. Anyone who has not used this methodology is their own loss. This technique almost totally eliminates EQ and greatly minimizes dynamics control.