An Unprecedented Recording: Rebirth for David Bowie with “Never Let Me Down 2018”

“Oh bop, fashion, Fashion!” David Bowie gushed. And while the once-in-a-generation megastar broke countless boundaries at style’s forefront…even the great David Bowie could be a servant to fashion.

Enter Never Let Me Down, his 17th studio album. Released in 1987, it was a record that achieved decent commercial success but generally poor critical reviews — with no one a tougher critic of the album than Bowie himself.

You can’t blame him for his well-documented disappointment.

It was the record directly after 1984’s Tonight (“Blue Jean”), which in turn followed a mind-boggling string of unforgettable records, rapid fire landmarks in musical adventure: Let’s Dance (1983), Scary Monsters (1980), Lodger (1979), Heroes (1977), Low (1977), Station to Station (1976), Young Americans (1975), Diamond Dogs (1974), Alladin Sane (1973), The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars (1972), Hunky Dory (1971), The Man Who Sold the World (1970), David Bowie/Space Oddity (1969), and his self-titled debut from 1967.

No one, not even David Bowie, could keep firing on all cylinders nonstop. Although he initially professed to be pleased with the 11 cuts of Never Let Me Down, which he co-produced with David Richards (Queen, Iggy Pop), Bowie soon changed his tune. By the early 1990’s he was public with his misgivings, ruing the “good songs that I mistreated… I wasn’t quite sure what I was supposed to be doing.”

A re-listen gives clues to his thinking. There are indeed Bowie gems on Never Let Me Down, like his soulfully bold opener “Day-In Day-Out,” and the title track where Bowie sings a gorgeous vocal line as heartbreaking, vulnerable and intimate as it is artistic. But often the record is too-big bombastic, replete with synthed-out drum and string replications stereotypical of “‘80’s production” where weird simulations and in-your-face gated reverbs dominate.

Such indulgences were collateral damage of synthesizer experimentation, an essential stage before people could eventually calm down and start hiring real players again. Sometimes it worked wonderfully – plenty of ‘80’s hits have endured for decades with just such characteristics. But it was a mismatch for Bowie and what he really had in mind for Never Let Me Down. Listening to the original you can hear how rarely the vocals and instrumental arrangements click, and how often they clash as on “Zeroes” where he seems practically shouting to be heard over the raucous guitars and rhythms.

Rare Rebirth

Mario J. McNulty was nine years old, living in Phoenix, AZ when Never Let Me Down came out. Maybe he even whistled along when he first heard the title track on the radio – he was no doubt learning best practices from Bowie. McNulty grew up a mega-fan of the man, and in a series of fortuitous twists became his trusted engineer later on after he moved to New York City and embarked on a GRAMMY-winning audio career: he produced/engineered/mixed for the likes of Prince, Nine Inch Nails, Laurie Anderson, Angélique Kidjo, Julian Lennon, Glen Matlock and many more. Among many Bowie projects, McNulty engineered alongside legendary producer Tony Visconti on the super-secret Magic Shop sessions for 2013’s The Next Day.

McNulty knew very well how much Bowie wanted to revisit Never Let Me Down. Back in 2008, Bowie had asked Mario McNulty to remix the track “Time Will Crawl” and record new drums by his longtime drummer, Sterling Campbell, along with strings. After the track went public, Bowie proclaimed, “Oh, to redo the rest of that album.”

It’s happened after David Bowie’s tragic passing in 2016, but now like no album ever, those tracks have received a miraculous second life: McNulty has produced and engineered an entirely new production of the record, with new instrumentation by Bowie collaborators Reeves Gabrels, David Torn, Tim Lefebvre and Campbell. Dubbed Never Let Me Down (2018), the record also boasts a string quartet with arrangements by Nico Muhly and a guest cameo by Laurie Anderson on “Shining Star (Makin’ My Love).”

The record was recorded earlier this year, when McNulty went into NYC’s Electric Lady Studios with Campbell, Tim Lefebvre on bass, who was in the ★ (“Blackstar”) band, along with Reeves Gabrels and David Torn on guitars. With all of them Bowie collaborators, they formed an optimal band for what now sound like brand new songs, featuring all new instrumentation and arrangements playing alongside David Bowie’s original vocal tracks. Nico Muhly, whom McNulty first met when they were both interns working for Philip Glass in 2001, oversaw the string arrangements.

The release from Parlophone Records is part of the just-launched David Bowie Loving The Alien (1983 – 1988), fourth in a series of box sets spanning his career from 1969.

Their work represents quite an achievement. Everywhere the album is now more natural, organic, listenable, beautiful, enjoyable, immersive, with more David Bowie available for your ears across the board. No longer buried in the layers, he is simply front and center where his inimitable voice belongs, made at turns joyous, dark and fearless, jamming on songs he loved with his band.

In this conversation with McNulty, you’ll be surprised by the complex web of psychological, philosophical, and artistic choices he made on the way. He reveals: Who is the true audience for this record? Of course Bowie made it for all of us, but it turns out Mario McNulty crafted these tracks into new classics with a very special audience in mind.

Compare the 2018 version of the title track…

With the 1987 original:

You moved to NYC driven in part by the dream of working with David Bowie. Do you remember your first session with him at Looking Glass? What were you called on to do as an engineer? What was it like for you working with him that day?

I’ve talked about this a few times so it’s not a secret, but the first time I really did something with David was actually in a rehearsal playing drums and subbing for Sterling Campbell who was unable to make it.

It was a rehearsal for a concert David was performing at for the Tibet House annual benefit at Carnegie Hall. The band was David, Tony Visconti, MCA/Adam Yauch, Philip Glass, and The Scorchio Quartet. It’s a lengthy story, but David and Tony Visconti knew me since I was an assistant engineer at Looking Glass studios at that time, and I had become friendly with both of them. Somehow they also knew I played drums so since they needed someone I was basically in the right place at the right time. I was nervous but thrilled, it was a surreal experience!

Over the years, how would you characterize the evolution of your working relationship with David?

I’m not sure how to answer really, but I know that as years went on I knew I was someone David trusted. I never had any bad moments with David, it was magic it seemed.

He had a remarkable sense of making me feel comfortable pretty much in whatever situation. We became friends outside the studio, we would discuss lots of things that weren’t in the musical domain, which was something I feel so lucky to have had with him. So as a working relationship, it was natural.

I also knew how he worked with Tony, and so many times it was just the three of us in a room. When I worked with him alone, we kept it organic. Seems silly, but David made it both relaxing and exciting at the same time.

In the process, how would you describe David’s approach to using the studio as a creative tool? How did he differ from other artists in that respect, for better and for worse?

He was really sharp about what he wanted, he would ask to move this, edit that, etc. There wasn’t any “worse” part as far I am concerned. By the time I was working with him he was a seasoned record maker, he had accomplished so much but never lost that edge. No other major artist comes close to his creative output, it’s truly astounding.

Why do you think his better instincts might have failed him during the production for “Never Let Me Down?”

He essentially was just checked out during this period, his own admission. It was a strange time for record making — in many ways, the ‘80’s had kind of been in overload. So many of the albums of that period just had too much of everything, and for some it worked, for many it didn’t.

His instincts clicked on very soon after the album was released, he was wanting to re-do some of the songs already with Reeves Gabrels in his next band Tin Machine. That never came to be, so here we are today.

How did he articulate his feelings to you about NLMD when you met over his idea to re-record “Time Will Crawl”?

David didn’t go into crazy detail, but he certainly made it known that he was unhappy with the production of the album, and this would be a first crack at doing something about it.

One of the main issues for him were the programmed drums, those had to go in his mind and that seemed obvious to me as well. This idea he had of re-doing something that had already happened in one sense, was something I respected David so much for. I don’t know of any other artist who has attempted such an experiment. It’s David being fearless and forward thinking, and not afraid of what anyone would think.

‘This Album Had to Sound Like a Band’

Fast forward to late 2017, when you knew you would get the opportunity to oversee a total redo of the album – how did what he told you shape your initial approach to producing, recording and mixing the record?

When I was contacted about this, it came as a surprise. I knew after the 2008 “Time Will Crawl” [remix by Mario McNulty] that David was very happy with it, and wished this to happen for the entire record, but really didn’t know if it would ever materialize.

So when I was finished with my initial discussions with both the label Parlophone and the estate, I knew already that everything I had discussed with David for “Time Will Crawl” would be very important to producing this record. I didn’t just use that, since that was only based on one song, I took from years of discussions with David about music, art, everything I could in my experience of being around him both in and out of the studio. So in one sense, it was like David handed me a very fancy demo of the album, and with that I had to produce a new album based around the songs and his vocal, so that core of Bowie is there.

In the process, what unique audio opportunity did you realize that you had?

In terms of an audio opportunity, the first thing of importance in the hierarchy was the musical production and what I needed to happen to support David’s voice and song. That was its own process for sure, but once each song had a direction, then I could think in terms of audio.

This album, at least to my knowledge, is unprecedented in what was accomplished. No other album had been re-done like this by an artist who disliked an old album in their catalog. I talked about this with various people, and we still couldn’t think of an example that was analogous. But one of David’s wishes was that the album sounded more organic, and less of an ‘80’s keyboard vibe. That meant acoustic drums, and quite frankly, in my opinion the album needed “air” and “feel.” David loved the sound of a “band in the room.” That was very important to me.

When I got the the Pro Tools sessions that had the tape transfers on them, I went through each song methodically learning what the actual content of the master tapes were. There was no click track for me to reference, I built a new click for each song, which was custom and drifted slightly always. Since the transfers for each song were from 48-track analog (two 24-track machines synced), there was always some drift, and also keep in mind that even with the programmed drums, those tempos could possibly drift from whatever the module was they were playing from in that original studio session.

I took an approach that meant this album had to sound like a band, real, organic, so that meant the reproduced sound was completely different.

Recording at Electric Lady: ‘Every Song Took a Transformation’

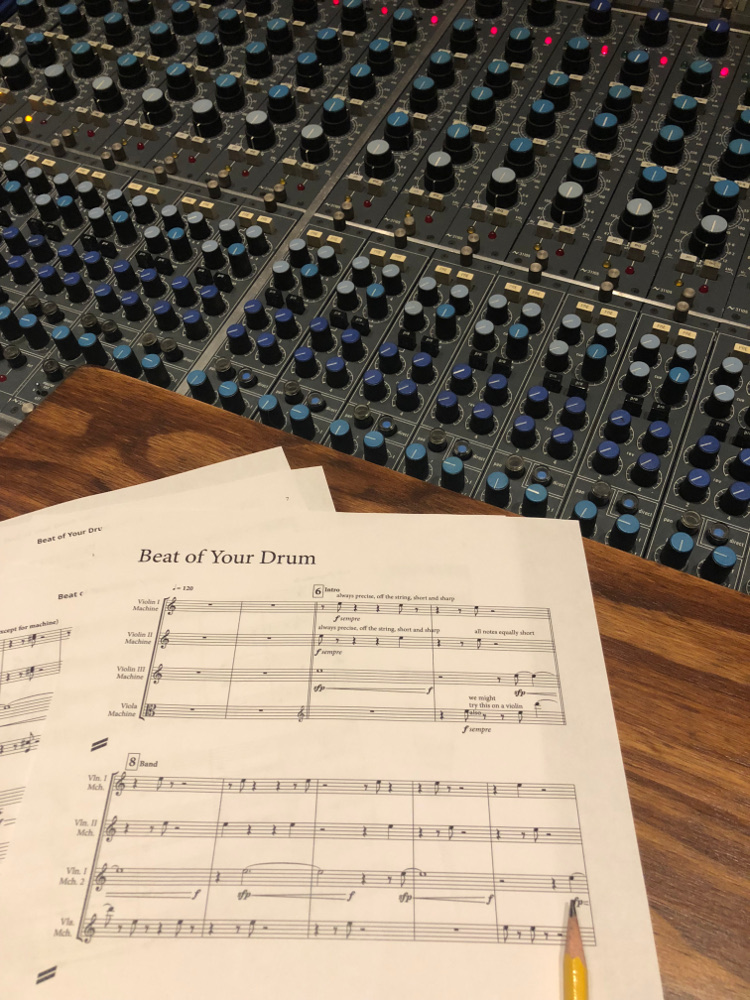

Let’s zero in on a song – you said you wanted to discuss “Beat of Your Drum.” How would you characterize David’s vocal performance on that song? How did it give you a core/roadmap to build the rest of the song around?

I think this is one of the best vocals from David, not only on this album, but ever.

It’s a stunning lead vocal, I wanted to make sure it was the main feature, not covered and in the background. In terms of a roadmap, you’ll notice how sparse his vocal arrangement is, and how his timing and pocket of his performance already start to dictate the feel.

There is a sense of space, which leaves the song ready for musical moments and counter melody. That timing and space is something David was incredible at.

Concurrently, what did you feel you were there NOT to do? How far did everyone feel they should go to update the songs, without overshadowing the original intent?

I was there to make a Bowie album, and not an album for anyone else, and the band certainly knew and understood that from the beginning.

It was a mantra of mine to have the band play as if David were in the room. There is a certain energy when David was there in person, and I wanted to try to bring that energy to what we were doing. The song was still king, and it was David’s songs, and everyone was respectful to that.

Luckily, the core band which was Sterling Campbell on drums, Tim Lefebvre on bass, and Reeves Gabrels and David Torn on guitars, all had their own history of working with David. It wasn’t hard for any of them. The additional musicians were Steven Wolf, who was a programmer on two of the songs, Nico Muhly, who did the new string arrangements, and one guest vocal from Laurie Anderson.

Why did you choose to record at Electric Lady? Please tell us about key recording decisions/signal path facts for recording guitar, bass, drums, keys…

Electric Lady Studios was the natural choice because I had already done “Time Will Crawl” there with David and he was happy with the results, so I didn’t change that formula. I was basically imagining as if David and I continued working after “Time Will Crawl,” and we just kept on going with the rest of the album.

So I set up the drums in a similar fashion, which was in Electric Lady’s legendary studio A. The bass, some guitars, and the new strings were recorded in that room as well. I loved the air and space I was allowed, it opened up the sound for the songs. The drums were tracked on the gorgeous vintage Neve desk, I used a bit of compression to tape here and there, nothing severe except for a few room mics.

I also had a set of old 414’s setup for an M/S recording in the middle of the room facing the drums. Usually I’ll only do this sort of thing when the size and sound of the room are suitable. I’ll always EQ to tape, that way I’m closer to what I want to hear when I’m mixing down the road. Sterling had his GMS kit sent in from SIR, and several snares, I also brought some of my snares as well so we were well stocked for each song. We had our usual vault of Zildjian’s to choose from, that is always fun for me.

Tim’s bass went thru a 3-way split from a radial DI to a dirty pedal chain, then to an awesome vintage Ampeg B18. The bass overdrive was Tim’s Darkglass Electronics vintage Microtubes XL pedal. He also kicked in his 3Leaf Audio Octabvre MKII, which is part of his signature sound.

The guitars were only done partially at my studio, Incognito, downtown and also partially at Electric Lady. For the ELS guitar setup, Reeves and Torn have their own custom setups. Reeves had a combination of pedals, his Line 6 Helix, plus we used a few different cabs. He had his signature Reverend RG1 with the sustainer and his signature Reverend Spacehawk, those two ended up being used the most. There was a gold top Les Paul bought in the middle of the sessions, so that made it on to “Beat Of Your Drum” at the last minute. Reeves also brought a real nice Breedlove acoustic.

A hit with the rhythm section: (l-r in the top image) bassist Tim Lefebvre, McNulty and drummer Sterling Campbell

Torn’s setup was a version of his ever-evolving LCR cab rig. This setup is especially great when in a big room like ELS studio A, I’ll have some room mics setup for this always. I can’t even begin to tell you what his processing is, he has a tall rack of gear that he plugs into which get split to his cabs. It’s common for Torn to send his dry signal to his center cab, and all the ambience and FX to the left and right cabs. You get the separation in the recording if you need it. I think much of Torn’s gear ends up being built for him or custom in some way, since he has such a particular way of playing and really specific needs.

The strings were more traditional in a recording sense, I used the studio’s old Neumann U 47, U 67, and U 87’s going through the Neve. The room mics alone on the strings sound great.

What were some surprises that came up as the song’s tracks came together? What were your own feelings then about the transformation of the song, and Bowie’s performance, with the new music that you recorded?

One great moment that I think was a surprise in a way was how “Zeroes” ended up. I had been working by myself doing my own preproduction trying to get a sense of what my plan was. Even though I went through this same process for every song, as I stripped away the previous recording, I was left with David’s lead vocal and his acoustic guitar. I had a moment, it sounded amazing and it reminded me of David singing on “Hunky Dory.”

When I was eventually in the studio with the players, they heard where I was going with this stripped-down approach immediately. David’s vocal performance was legendary. There was a great little moment when Reeves and I looked at each other in the control room and said, “Why isn’t this a single”? David’s voice is truly fantastic on the entire album.

Every song took a transformation, some much more than others, some more conceptual that others. But one thing I should mention is that I never really know what that transformation is until it’s done. I was creating the form and framework and conditions for each song, but the musicians play a valuable part and I don’t know what that is until they’re playing in the studio, that keeps it fresh. David worked that way and it has been an incredible influence on me.

Mixing it Down

The Mix: how did you approach mixing “Beat of Your Drum?” Tell us about your mix setup at Incognito Studios.

My mix setup at Incognito is a Pro Tools HDX rig outputting to a Dangerous Music 2BUS summing amp, so it’s an analog/digital hybrid setup which is pretty common now. I use analog gear if it’s suitable.

I have been digging my Dangerous BAX stereo EQ, which usually feeds my Pendulum Audio ES-8. The ES-8 is really nice, I usually will keep it in dual mono, and it won’t compress much at all, but it has a very nice tone to it. I’m loaded with plugins, lots of stuff from McDSP, Waves, SoundToys, plus Eventide has been real good to me with the Anthology set and the Blackhole reverb, which I love.

For monitors, I use Yamaha NS-10s with a Bryston and Focal Twin 6Be.

For “Beat Of Your Drum”, I wanted to have a very open and grand feel, lots of punch and dynamics. Everything in the track had to breathe, the strings had to be there but still like a cloud around David’s stunning lead vocal.

Specifically, how did you approach David’s vocal?

Creating space is the first thing, that happens before the mix. I don’t want instruments or fluff cluttering his voice, its needs to shine and stand out. So once I have the right instrumentation and arrangement behind his voice, the mix gets easier, because my automation isn’t as severe.

Now if more space is needed after all that, then carving and rides are needed, that’s normal but the more I can do beforehand the better. Each section had changes in vocal effects, to lift the section differently. The verse is so open and sparse, you can hear more detail in the vocal effects and delay throws.

What were some key mix tips and tricks you can share about mixing that song?

I would say the best thing I did for this song specifically is getting the arrangement right even before I sit down to mix. I was lucky in this sense because I was producing the track — that isn’t always the case, and I may be mixing a song where the chorus or a certain section has really too much going on but I still have to make it work sonically. After that, I think the key is keeping the song very dynamic, which makes it more exciting sounding. Don’t be afraid of the automation, it’s your friend!

The Song and the Songwriter

Looking back, to what extent were you concerned about what David would have thought of your decisions? Ultimately, who were you making NLMD 2018 for –David Bowie, his fans, and/or his family?

I was concerned really all the time, every day in every decision I had to make. I don’t mean it to sound like I was stressed at every moment, but this was made for David, no one else. I’ll never know what David would have said, I only had the blueprint from him and it was also in my mind, I did my best to try and honor that.

What would you say you learned about separating the songwriter from the song and the production in the process of making NLMD 2018?

I think the only way I can answer that is when making an album, you truly can shape the direction it can go, the sky is the limit, and really the song is your guide.

This album is a great study now in the sense that you now have two albums… same songs, same vocals, same Bowie… but two completely different albums and that purely comes down to production. The songwriter is still there, but the production process is important and can shine if done well.

Concurrently, what did you learn about the “’80’s sound” while producing NLMD 2018? How would you characterize some of the signature sounds of that era that are present on the original NLDM? Why do those characteristics sometimes translate as classics, and others come across as dated like with NLDM?

The ‘80’s sound that most people talk about are big gated reverbs, cheesy clean synths, and treble for days! Those traits all had a big part of the original NLMD.

I think there were a lot of bands, and very major successful bands, that didn’t know how to adapt to the ‘80’s sound. It’s very interesting to think about, but many of the bands that come up in that era, don’t sound dated: Depeche Mode is an example I’ve used before. None of their albums sound dated from that time period, they came up in the era of synths and MIDI. It was new, but they were learning how to make songs and records that way.

Older groups from maybe the ‘60’s and ‘70’s, came up differently and were used to a band in the room with microphones. I think many groups had to take an album or two to adjust!

As you stated earlier, you said this was a unique project in the annals of popular music production. How did this unusual assignment help to change you as a producer and engineer?

I’m not sure there will be another album quite like this for me personally, but it certainly helped me realize how much can be done with a song in any form. The demo could be hardly anything but a voice and key, or it could be a fully-produced album. The song can take you many places if you allow it to.

Finally, how would you characterize your journey of going from an intern on a session, to part of David Bowie’s inner circle in the studio, to being the executor of his artistic vision posthumously? And how did the making of NLMD 2018 further your understanding of David Bowie as a recording artist?

I feel beyond lucky and forever grateful to David, it was a dream come true and still is like a dream. I’m also grateful to Tony Visconti for taking me on as his engineer on not just David, but many years of projects.

David was a private person, but in the studio it was relaxed and fun. I think he trusted me and that is why I was able to keep working with him for so many years. This project coming to fruition was nothing I ever expected, but his artistic vision was his own, I am trying my best here to execute that vision and I hope it now stands tall in the Bowie lexicon.

It did make me understand that not all artists are happy with what they have done. He was cool enough to say, “I didn’t like this album I did way back, let’s try again”… and there was never anyone cooler than David.

- David Weiss

Please note: When you buy products through links on this page, we may earn an affiliate commission.