Hip Hop, History and the Studio: Fresh Revelations Unveiled in “Contact High”

Hearing hip hop history has never been easier. Between Spotify, Apple Music, Tidal, YouTube and all the other streaming services, hip hop fans can simply pull monumental albums out of the air and indulge their ears to excess.

The book “Contact High: A Visual History of Hip Hop” brings a whole new perspective to hip hop history.

But seeing hip hop history? That’s proven much, much harder— until the new book Contact High: A Visual History of Hip Hop came out. A collection of photographic essays of hip hop legends assembled by the acclaimed music journalist Vikki Tobak, it’s a landmark tome that reveals the intimate moments around iconic images by sharing photographers’ contact sheets.

Brilliantly bound in a gorgeous presentation, Contact High stands as a work of art all its own, while simultaneously celebrating the art of photography — which in turn is celebrating the art of hip hop’s greatest pioneers. The last shoots of Tupac Shakur and Biggie Smalls are there, as is Al Pereira’s shoot of Queen Latifah on the set of “Fly Girl,” Jerome Albertini’s shoot capturing all of Wu-Tang Clan at once, and scores more — many never seen before — including A Tribe Called Quest, Nas, N.W.A., Kanye West, 50 Cent, Jay-Z, Nicki Minaj, Eminem, Kendrick Lamar, and Lil Wayne.

The result is an indispensable visual record of the genre, being hailed by some as “the Bible of hip hop photography.” Even better yet for the producers, mixers, and gearheads among us is the presence of several collections taken within the sanctity of the studio. Shenanigans at the console with A Tribe Called Quest, sonic immersion for J Dilla before a bank of faders in his home facility, and Jay-Z in deep thought plus a pair of microphones are just a few of the audio-centric surprises inside Contact High.

Recognizing the studio as “a sacred space” for hip hop is just one of the many insights from Tobak in this interview with SonicScoop. Here she discusses her personal journey and much more about the creation of Contact High, a work that has instantly become inseparable from the hip hop history that it so masterfully documents.

Contact High has been extremely well received since its launch in October. Have you been surprised by the amount of attention that the book has generated?

I’ve been a little bit surprised at just how much people love it and really are drawn to it, as a historical document. A lot of music books come out, but I’ve been getting the sense that this book will kind of stick around for the long run, because people are really responding that it’s a historical book.

I’ve been more surprised at how young people are really using it to learn about the history of the music and the photographers. Then, older people are like, “Yes. This encapsulates what it was and all those moments that we experienced.”

One other thing that surprised me, though, is just how much the music world has embraced it, relative to the photography world. When I was writing it, I was really thinking of it as a photography coffee table book, with music as the premise, but I’m surprised that the photography world hasn’t been a little bit more critical in looking at these photos in context of the history of black photography.

I’m sure you had some ideas about why this book was needed, when you decided to write it. But what additional insights have you learned, now that it’s out there in the world?

I think people knew what hip hop was, they’ve heard about the history of it from so many different perspectives. The photos were always just sort of a given, although they weren’t presented in this collective way. And this was a very key time [in hip hop history].

Nas and his producer team in the midst of making “Illmatic.” (Photo by Lisa Leone. Reprinted from Contact High. Copyright © 2018 by Vikki Tobak. Published by Clarkson Potter, an imprint of Penguin Random House, LLC.)

I think what surprised me the most is the fact that it was so obvious, that these photos were in the collective consciousness that all music lovers share, especially in the hip hop world. But it’s like, “Oh. Here they are. Of course.” Like, “Boom. I remember where I was when this came out. I remember where I was when this album cover came out. I remember where I was when I first saw this photo.” It means so much to people. It’s really bringing people back to individual moments in their own lives, what was happening for them, when they first saw that photo.

That must feel positive to help people to reconnect with something so fundamental like that.

It’s an amazing feeling, because it definitely makes the book feel bigger than any one photographer, than any one artist, than any one writer. It makes it feel like it’s bigger than just any one person, or artist. That it doesn’t belong to me. It belongs to this bigger collective of people.

Whenever you create something like that, whether it’s a song, or a piece of art, that is a great feeling, when it leaves your hands and starts to belong to this greater circle. It’s a weird feeling, and it’s a really cool feeling.

Deeper Inside the Music

You were already a hip hop expert, before you started “Contact High.” What additional insights did you learn personally about hip hop culture from writing the book?

I learned the individual stories of the photographers more. That was the nature of what I was researching and interviewing, but learning how each and every photographer came to photographing hip hop is also really fascinating.

One thing I noticed about hip hop, versus other genres, is that a lot of the photographers were coming up and making their way alongside the artists. The photographers, themselves were really young. A lot of them were young men and women, Black or Latino descent, who weren’t classically trained, who were just drawn to something on a gut instinct and weren’t always on assignment, or anything. Learning their individual stories was something that I learned.

Then secondly, I also had to analyze, because a lot of people were like, “Well, why are you writing this book? Why were you drawn to hip hop?” I found myself having to answer in a more-linear way than I always have, because to me, you live your life and it just makes sense, but because I was being asked by people who don’t know me and don’t know my history, or don’t know how I came to love it, I had to sort of retrace my own steps. I had to have a more-linear version in my own head of, “Why did I fall in love with hip hop and then, come to write this book?

Speaking of the photographers, like the photographer Glen E. Friedman that did the photos for Public Enemy’s album It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back. He was going to scratch the photo that they liked the best, just due to his own artistic stance! But then Hank Shocklee of the Bomb Squad told him not to.

And that’s one thing that I really wanted to do with this book, is talk about not just the person in the main image, and not just the photographer, but also talk about who else was around. In a lot of these iconic images, you don’t see the producers. You don’t see the neighborhoods. You don’t see all the people that were around that created these moments.

By telling the stories through the contact sheets, you can see a lot more of the layers. The story of the Bomb Squad comes out because you see the process and you see who was involved at every step. The contact sheet was sort of a way to do that. Otherwise, you don’t get a lot of the Hank and Keith (Shocklee) and everyone that was around, and where they were.

Audio Caught on Camera

Drilling down to the music production side, what new insights did you glean about the history of hip hop in the studio? What role has audio technology — whether we’re talking about turntables, microphones, the studio itself — played in the evolution of hip hop?

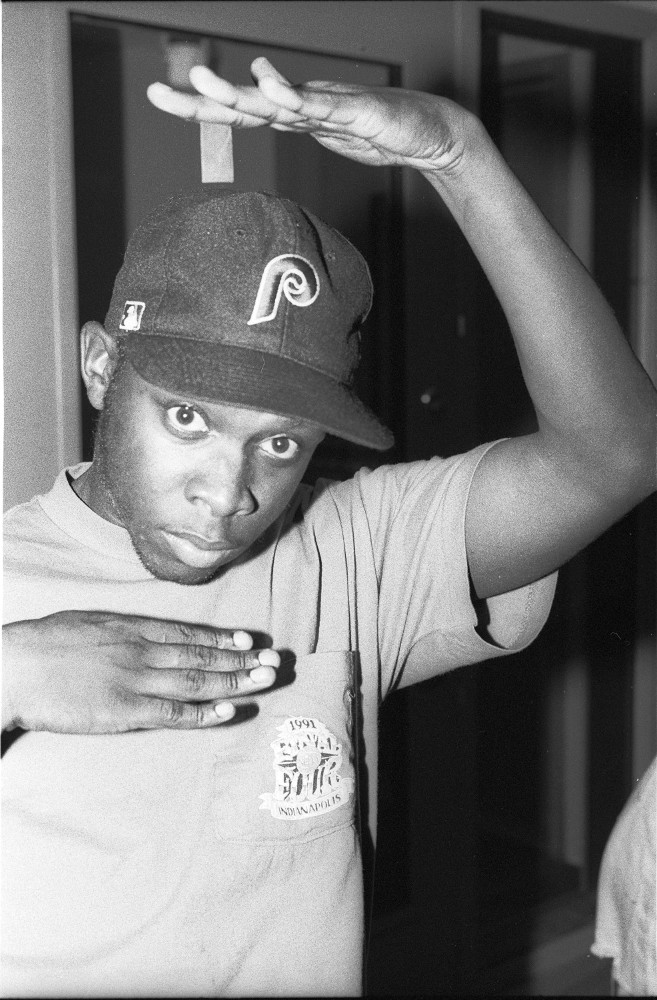

Phife Dawg of a Tribe Called Quest strikes a studio pose. (Photo by Al Pereira. Reprinted from Contact High. Copyright © 2018 by Vikki Tobak. Published by Clarkson Potter, an imprint of Penguin Random House, LLC.)

I wanted to make sure that you saw the studios, because they were so important in what kind of sound was being made, and definitely certain hip hop artists had certain allegiances to different studios. For example, when you hear Danny Hastings and RZA talking about the making of the Wu Tang cover, Enter the 36 Chambers, they talk about how they’d spent weeks together at Firehouse Studio before they shot the album cover. That was where they kind of visualized what would be and heard the music. That space was really important.

Then, of course, Young Guru was in there, talking about his experience with photography, and how Guru and DJ Premier worked at D&D Studios. That was a space where they felt comfortable and would allow photographers in.

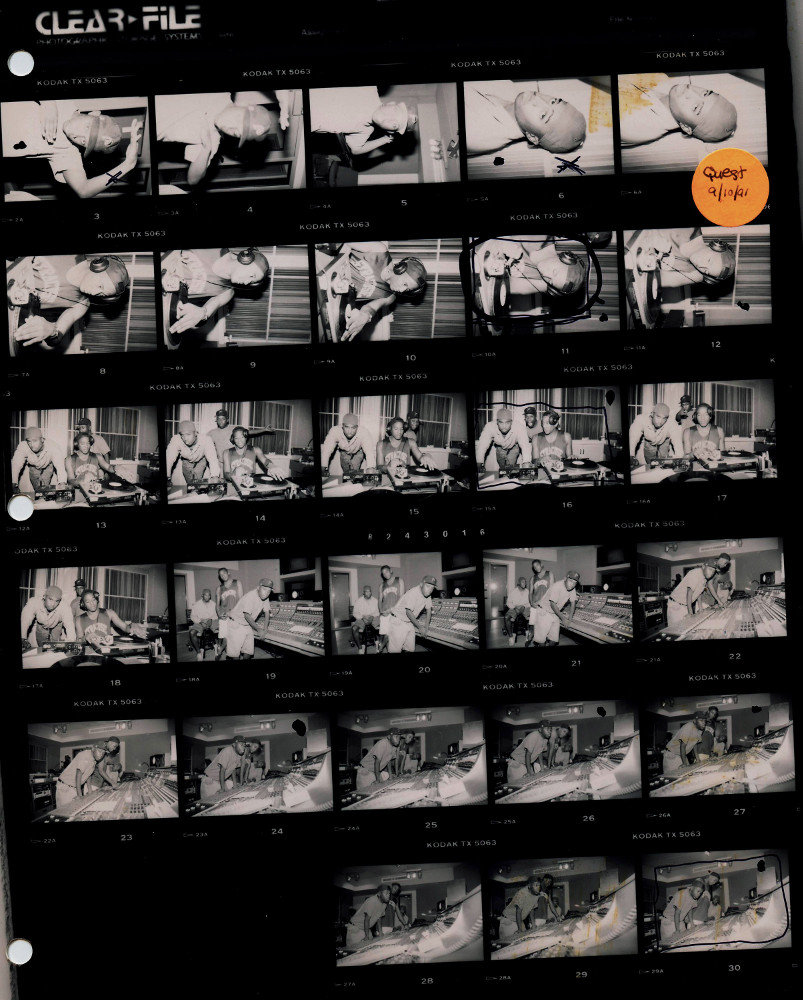

And I actually don’t know what studio it is, but for the spread on a Tribe Called Quest, there’s a very famous photo of Phife Dawg, sort of framing his face with his hands. In the rest of the contact sheet you can see that they were actually in the studio recording. Otherwise you wouldn’t have known that, that was just a moment of him being goofy in the studio.

In my core time with hip hop, I spent a lot of time at D&D Studios with Guru and Premier, while they were recording various things and I understand that the studio is a very sacred space. Who gets let into that space is a very intimate choice, and it can kind of screw up a whole vibe, or add to. It’s just a big deal. I learned that first hand, working with Gang Starr and being in those spaces. I wanted to make sure that, that element was represented. A really good example of that in the book also, is the Lisa Leone series of Nas recording Illmatic.

I loved that series of pictures.

You see all the producers and you can almost feel the tension in that studio. That was Sony Studios, where that was taking place, but like Lisa said, “You felt like something important was happening, you just knew.” The photos really capture that.

…and the contact sheet the Phife Dawg image comes from — note the large frame console in many shots. (Photos by Al Pereira. Reprinted from Contact High. Copyright © 2018 by Vikki Tobak. Published by Clarkson Potter, an imprint of Penguin Random House, LLC.)

Many Sides of Jay-Z

Of course, I wanted to ask you about the J Dilla photos — because this is in Detroit — about that shot of him at the console [at his home studio in Clinton Township]. What do you like about that contact sheet?

I like that they’re in the studio and I like that they’re in Detroit, because both of those were things that were indelibly defining to Dilla’s career and who he was.

Experimental beat master J Dilla deep in thought. (Photo by Brian “B+” Cross and Eric Coleman. Reprinted from Contact High. Copyright © 2018 by Vikki Tobak. Published by Clarkson Potter, an imprint of Penguin Random House, LLC.)

That was his happy place. If you were going to photograph someone like J Dilla, you’re going to photograph him sitting at a board, or in front of an MPC. On the contact sheet, you see the Detroit River. You see parts of his back yard. It feels like Detroit, for anyone that’s lived there, those particular photos and moments just really have this air about them, that feels like Detroit.

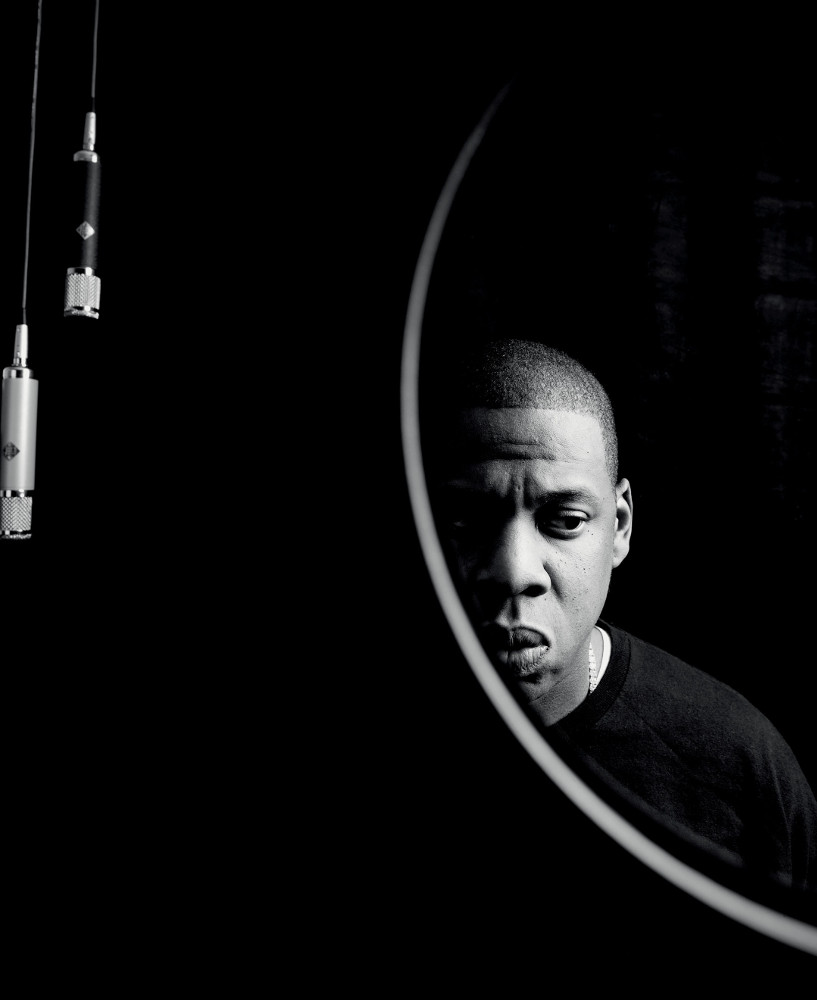

Another one I wanted to ask you about is the one that Danny Clinch took of Jay-Z in his studio. I think that’s a very cool shot and it doesn’t scream studio at you, but the microphones are there. I’m interested in what spoke to you about these particular photos.

Well, that particular one, by Danny Clinch, it’s a digital shoot. I only wanted to include digital shoots if it were for a reason, to tell a story, or if it served a purpose. I wanted to include the Jay-Z photo, because Danny Clinch is a photographer that had shot analog all his life. Then, this was his first shoot that he was starting to shoot in digital. I wanted to talk about how certain photographers were transitioning into shooting digital and how that maybe changed, or didn’t change their practice.

Then, the other reason is that one thing I wanted to do wherever possible, is show artists at different stages of their career. Jay-Z was perfect , because I had his first shoot [earlier in the book]. Then, I had a shoot where he was just starting Roc-A-Fella Records and was just starting to make his way. That’s where the World Trade Center photo that Danny Hastings took comes about.

A classic side of Jay-Z. (Photo by Danny Clinch. Reprinted from Contact High. Copyright © 2018 by Vikki Tobak. Published by Clarkson Potter, an imprint of Penguin Random House, LLC.)

Then, this photo that Danny Clinch took was definitely when Jay was already a powerhouse and only was giving the photographer 12 minutes with him at the studio, where he already happened to be working. It’s a very tight portrait. It’s almost like Blue Note, very classic.

There’s no signs of wealth around. Where you look at earlier photos of choices that he was making, the first one he wanted to be in front a yacht. He wanted to be in front of the World Trade Center. Then, he wanted to be in front of the World Trade Center again, to show that he’s building and thinking like a Wall Street guy. By the time Danny Clinch comes to the studio later on, you get a very simple, complex Jay, at a different part in his career and understanding where he fits in on this continuum, back from the jazz world to now. That’s why I included that photo.

Reconnecting with the Beats

I’m sure you went through quite a journey in assembling Contact High. What albums did you personally get reconnected to personally, musically, in the course of making this book?

That’s a good question. I started listening to a lot of Gang Starr again. I went back and I listened to Hard to Earn and I listened to Moment of Truth. I went back to those two albums, even though I was at D&D when they were recording Hard to Earn. I know that album inside out, upside down. I was also kind of sad in writing the book that Guru from Gang Starr was not around, because he was someone that I was really close to and we had a lot of deep conversations about photographs and history.

I was so young, that I guess now, all these years later in writing the book, I got to thinking, “I wish that he could see the book.” It just made me go back. Also, I just wanted to re-listen to a lot of his lyrics, because as I was looking closer at the imagery, I just started to re-think about how brilliant he was, and how connected his lyrics and his imagery and the way he dressed and all of that were.

Then also, Nas’ Illmatic. I always loved that album, but I just went back and re-listened to it. I also recently got the opportunity to do a talk with Large Pro, who’s in that shoot and who’s responsible for much of Illmatic and discovering Nas among others.

Also, Dilla and MF Doom on Madvillainy — those albums were later in the game for me, personally, because I’m definitely an early-to-mid-‘90s girl. Those albums were slightly later. I re-listened to them, because in writing about the Madvillainy shoot and Dilla, I wanted to pick up on any nuances that I may have overlooked or missed. Those, I had to listen to with fresh ears but the other ones were, like you said, a re-connection and a reminder of why I fell in love with the music in the first place.

Why did you fall in love with hip hop?

When you grow up in Detroit music is really, really part of the fabric of the city and music explains so much about everything in that city. That was always second hat for me to kind of listen to music and expect it to tell stories of a city.

When we were in high school and hip hop started to come out, I was already part of that club scene in Detroit, which was mostly early techno and house music. It was sort of like this outsider culture that I really connected to.

Hip hop was an extension of that to me, and that was the reason why I left Detroit and then moved to New York. That was the voice of the moment. That’s why I fell in love with it: because it translated everything that I was seeing and feeling.

- David Weiss

Please note: When you buy products through links on this page, we may earn an affiliate commission.