New Gear Review: Kick by Avantone Pro

Avantone Pro unleashes their take on sub-frequency microphones with Avantone Kick—can it become your top way to capture bottom end?

Most producers and engineers would probably agree that low end is the most difficult part of the frequency spectrum to get right.

Muddy, indistinct bottom end is a tell-tale sign of inexperience in an engineer or mixer, and a demo reel filled with examples of this kind could be a clear deal-breaker when trying to land your next project.

The low end is so hard to get right in part because bass frequencies tend to behave unpredictably when referencing your work across different systems. And there is a great risk that your decisions around the bottom end will sound skewed on playback if your listening environment is not decently tuned.

Though getting a pro-level low end balance may not be easy, there’s plenty of ways to help achieve it. When you need to control an overabundant low end, filters and dynamic EQ can take you a long way. If it’s earth-quaking bottom you’re after, you can try to beef up your low frequencies after the fact with pitch-shifting effects or additive bass plugins like Waves’ Renaissance Bass. But the very best way to get powerful-sounding lows is at the source.

I’ve spent a lot of time playing drums in recording studios and on the road, and practically everywhere I go, there it is: the now-discontinued Yamaha Subkick. These big transducers are found everywhere for good reason: because they’re awesome. Unfortunately, they’re also not being made anymore.

Like so many other engineers, I have even gone as far as fashioning my own makeshift large-driver sub-mics by wiring extra speakers in reverse. It’s a fun and easy project. But it has its drawbacks compared to a custom-built solution.

The physics of sound suggests that capturing the larger low end sound waves from things like kick drums and bass cabinets with a larger transducer makes a lot of sense. This is why I back the idea of a sub-kick style of mic so much. And with some careful carving of EQ to make low frequency elements co-exist happily, you can achieve a very robust, non-algorithmic quality to the low frequency content in your productions.

Enter into the sub-frequency mic fold Avantone Pro, purveyors of some very popular mics and speakers based on classic designs. They’ve recently released the Avantone Kick, their own flavor of big-driver mic, to help fill the gaping hole left behind by the loss of Yamaha Subkick. I was excited to put it to use.

Features

Upon first glance, it’s obvious that Avantone Kick bears a striking resemblance to the discontinued Yamaha model. Though a different color scheme, they both share the same overall approach to design. Both models feature 6” drivers that are housed in an actual drum shell, with real drum hardware and mesh heads. The speaker (mic “capsule”) can be seen facing outward on one side, protected by the semi-transparent mesh head.

I was actually sent the prototype of the Avantone Kick, which was confirmed to be the exact same design that went into production. This was fine by me as I love gear that’s got a story. When it showed up, it was in immaculate condition, looking not one bit different to my eyes than the version that hit the shelves. It being a prototype, I assumed there was a decent chance of a more visually “in-progress” unit, which also would have been cool.

The Avantone Kick boasts a frequency response of 50Hz – 2kHz, a figure-8 polar pattern, and an output impedance of 6.3 Ω. A standard male XLR connection is available just like on any other microphone. At the heart of its design is the AV10-MLF driver—the same driver found in their popular CLA-10 emulation of the classic Yamaha NS-10, in partnership with Chris Lord-Alge. The decision to use this driver is most appropriate because after all, before sub-frequency mics were being manufactured, it was the commonly-found spare NS-10 drivers that engineers were using to wire in reverse.

But unlike the often-exposed and shoddily-mounted drivers in these original rigged studio setups, the Avantone Kick comes sturdily housed in a 10” birch drum shell which connects to a heavy duty double-braced drum stand. Assembled, it bears the feeling of heft and robust build quality, weighing in at over 10 lbs. Although I am not excited to add any extra weight to my drum hardware case, the extra pounds for build quality are welcome here.

In Use

The obvious source material to put under review was a kick drum and a bass cabinet, and I also ran some white noise through a Dynaudio BM5A MkII studio monitor. For all tests, the Avantone Kick was placed on-axis, approximately 5” in front of the source. And phase with complementary mics, of course, was checked.

The kick drum used was a 22” Ludwig Keystone Badge, circa mid 1960’s. It was stuffed with a blanket, which created a nice, vintage “knock”. There is no inherent “big” or “deep” quality naturally present in this drum. I was hoping the Avantone Kick would give it some “thump” without making it sound like something it is not.

It was easy to get a good sound here and move on quickly when sneaking it into the drum mix. With no EQ (I wanted to wait to hear what it did on bass), but a little bit of compression and a touch of limiting, it fit unobtrusively into the sound of the kit, and added a very pleasing sense of natural size that simply isn’t attainable with an algorithm.

Here is a sample of the Avantone Kick track solo’d, playing isolated single hits that increase in dynamics:

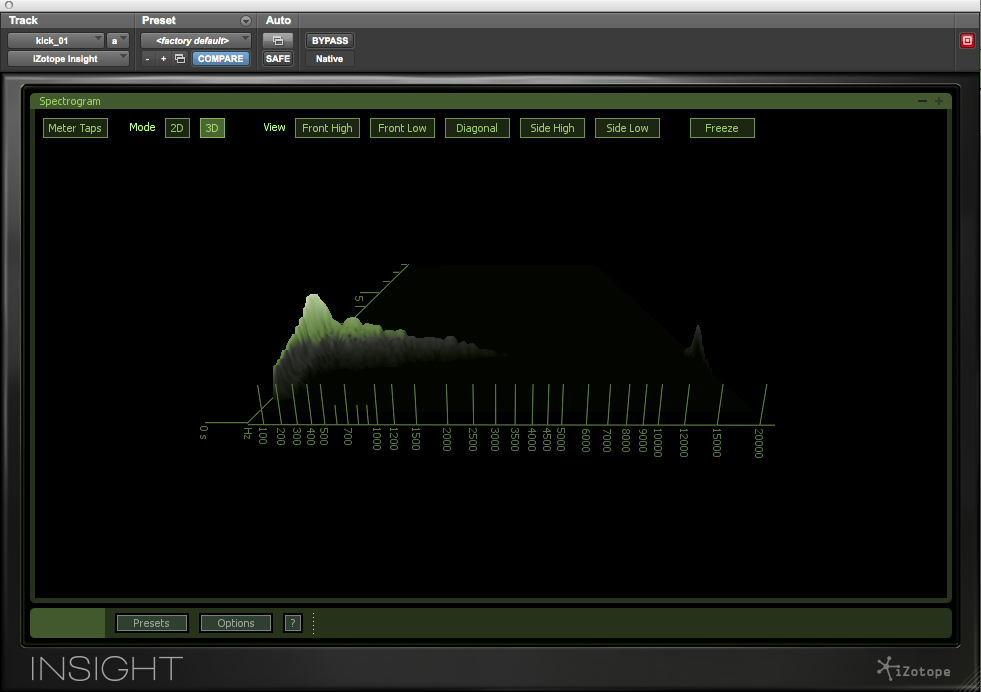

And also, a snapshot from both the frequency spectrum analyzer and spectrogram in iZotope’s Insight:

A kick drum quarter note captured with Avantone Kick, as seen through iZotope Insight’s spectrum analyzer.

A kick drum quarter note captured with Avantone Kick, as seen through iZotope Insight’s spectrogram.

The Avantone Kick, as expected, extended the lows quite nicely when tucked underneath the main bass amp mic (with a touch of DI mixed in as well for detail). I got a balance that felt decent among the three elements in solo, and brought the bass up against the drums.

For copyright reasons I am unable to provide the audio sample for the bass, but I am happy to report that multiple instances of the Avantone Kick seem to co-exist rather happily in a working mix scenario for a rhythm section. After a few brief moments of EQ carving, which I’m sure I will further address in the mix, and I’ve got a brand new flavor of low end available at my disposal. And one that feels less digital than what I’m used to, hearkening back to when rock records had massive budgets and bands were moving air in big rooms.

To be clear, I’ve gotten plenty of great low end sounds using EQ or other methods, and having a sub-kick at the ready will simply provide another means of getting there. But I have a feeling the sub-kick method will be adopted as primary and soon supersede my need for applying a more digitally-based treatment for low end after the tracking phase.

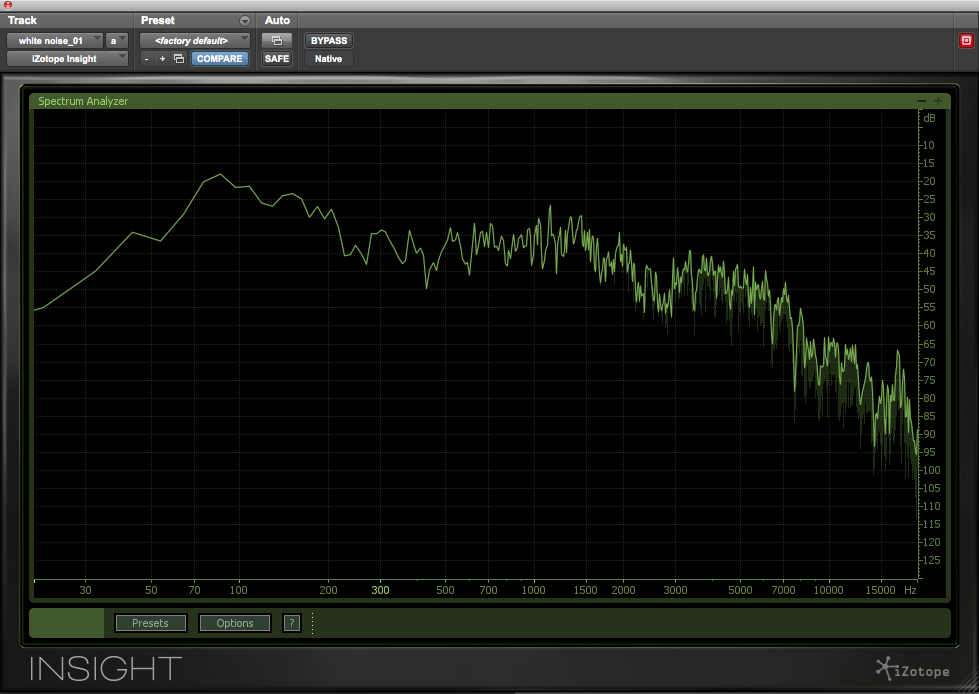

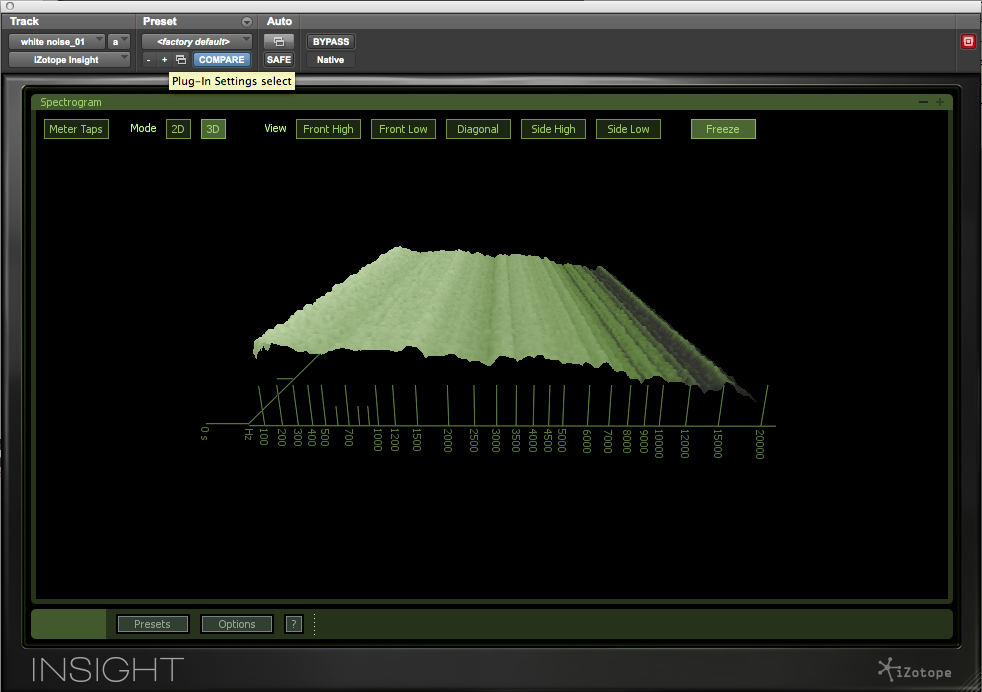

Lastly, for fun, I wanted to hear how the Avantone Kick captured white noise, and what it looked like laid out on the frequency spectrum and further, a spectrogram:

In general, I would like to be applying as little processing as possible (unless used for effect) in a mix scenario, and the Avantone Kick puts me in a position where I mostly foresee myself using subtractive EQ. I love the idea of this, especially pertaining to low end.

Although I haven’t gotten to the mix phase with the material used for this review, I am already confident that this new flavor of low end feels more organic and rich than even my best efforts via using an algorithm. It will take some work to learn exactly how to EQ both the kick drum and the bass in order for them to play perfectly well together, but I’m fully confident that what’s needed in the track was captured by the Avantone Kick.

One final note I’ll add is that dynamics treatment in particular for an element like a sub-kick is crucial. If not properly controlled, later compressors in your signal chain (for example, your drum bus or mix bus), can behave unpredictably and react drastically to overly-dynamic low end material. If new to using a sub-kick, I urge you to get its dynamics under control as early in your chain as possible. I would suggest, whether with kick drum or bass, compressing your signal to taste from a creative/mix standpoint, then limiting it to protect against any big jumps in amplitude. Your ears, and your gear, will thank you later.

To Be Critical

I’ll precede this by saying that my one and only critique of the Avantone Kick is somewhat null. I’m picky about drum hardware. I only use designs that have fully-variable pivot points (ones that don’t employ two sets of interlocking teeth) because it allows for pinpoint-accurate adjustment of the angles of your drums and cymbals.

Initially I was less than thrilled to see an interlocking-teeth design on the Avantone model, but then it occurred to me that this unit is a microphone, and its upward/downward angle is essentially almost completely irrelevant. The stand feels sturdy, and I would trust it in both studio and stage settings without thinking twice.

Summing it Up

After just one session, I consider the Avantone Kick something that I will need to have for every future drum and bass setup. Even if you’re not looking for super big and deep lows, you can filter it, and it’s still helpful to have your low frequencies captured by a larger capsule. Again, it’s science.

The Avantone Kick is priced at $349, which is not an amount I would think twice about when purchasing a high quality dynamic microphone. With the AV10-MLF driver priced at $149, that puts all added electrical and mounting components, drum shell and parts, plus the stand, at around $200. If you’re hesitant to take the plunge, download the audio samples from this review, and drop the kick drum underneath a familiar drum session—see for yourself!

I, for one, will always make sure to have the Avantone Kick in hand for a crucial drum or bass session.

Please note: When you buy products through links on this page, we may earn an affiliate commission.

[…] Muddy, indistinct bottom end is a tell-tale sign of inexperience in an engineer or mixer, and a demo reel filled with examples of this kind could be a Read more… […]