New Software Review: Harrison Mixbus 32C

Harrison applies the large format console aesthetic, workflow and mindset to their full-featured DAWs, Mixbus and Mixbus 32C.

Writing a fair and complete review of an entire DAW is a daunting task, to say the least.

A DAW is much more than just a recording device. It’s more than an editor and more than a processor. It’s an entire studio environment with complex workflow possibilities and constraints alike.

When you become adept with any one DAW, it becomes a bit like a home office that you are used to and able to work quickly and confidently in. Stepping outside those bounds can be daunting.

It’s a sobering moment when you realize, for instance, that the “switch screen” hotkey in one DAW is the “nudge clip to the left” hotkey in another. (A moment that leaves you to wonder how many timing and phase relationships you’ve ever-so-slightly destroyed.)

But in the modern studio business, can you really afford not to check out how the industry is changing and what other offerings are available? Plus, an extra DAW in your back pocket means that an inspired session will never fail because one piece of software does.

With that in mind, Harrison offers up a whole new type of DAW to add to your studio with their Mixbus software, and with an alternate version, Mixbus 32C. Both aim to bring a more analog and more human workflow to the DAW experience. As a company, Harrison has a long history and impressive pedigree. Their first analog console offering was the Series 32, released in 1975. (For a sense of time and scale here, the first commercially available SSL console was released in 1976.)

Through the 70s and early 80s Harrison continued to make analog consoles, including the first fully automated console. The 90s heralded the introduction of their first digital console, and to this day Harrison continues to produce world-class consoles, both digital and analog. While their name may not be as famous as SSL or Neve, their consoles are in use in top film and music mixing studios around the world.

My primary DAW has always been Pro Tools, so all of my comparisons will be based around that. In the case of both DAWs, searching the forums when I encountered problems revealed a list of problems I never had. I’ve generally had good luck with Pro Tools in the past, but there have been issues, some of which were never solved. And there are definite critiques I have of Pro Tools that others probably think of as a cool feature. The point being: your mileage may vary.

With such a long history of console manufacturing, Harrison’s stance on DAW construction is not surprising. They have made it clear, in both literature and layout, that their goal is to more closely emulate the feel and sound of mixing on an analog console, and not a “container for plugins”. Let’s take a closer look at Mixbus.

Features

The two DAWs, Mixbus and Mixbus 32C, are for the most part similar. 32C has more busses, but the overall feel and functionality is very similar. The real difference lies in the sound, as standard Mixbus is modeled after the overall sound of Harrison consoles while Mixbus 32C is end-to-end modeled after one specific console—the one owned (and still used) by Bruce Swedien to mix Thriller, Bad, and a ton of other records. This review is based on the Mixbus 32C model.

While Mixbus may have analog dreams, it is still very much a full-fledged DAW in terms of its feature set. All aspects of music making can be accomplished inside Mixbus; this includes recording, mixing, sequencing, using MIDI tracks and virtual instruments, etc. It even supports sync for video and can lock up with other systems.

Like most DAWs I’ve used, Mixbus has a few different screens to work from, mainly the editor view representing our multitrack, and the mixer view, representing the console. There are of course other windows that can be opened. One of my favorites is the meterbridge, a fully-sizable group of meters that can be set to a large number of metering standards used around the world, in broadcast, film, and music. Additionally, these meters have buttons for input, record enable, solo, and mute. Using a touchscreen as an additional monitor featuring this window would make recording and overdubbing with multiple musicians much easier to wrangle. Sadly, there is no way to use the transport as a separate window, which would also be nice.

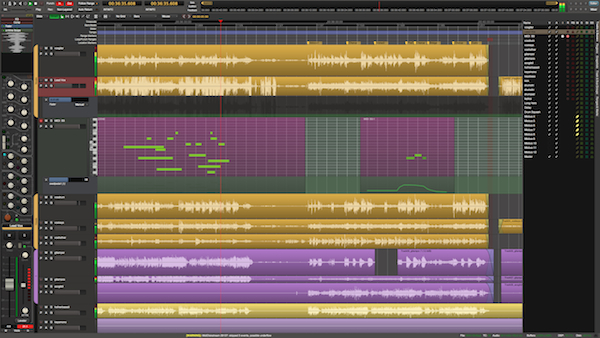

The Editor window is laid out in a mostly comfortable and familiar fashion. Across the top are the transport controls, editing tools, playback modes, counters, selection and song map. Many timeline lanes show common units (min:sec, bars & beats, timecode, tempo, meter, etc.), but there are also some very useful lanes such as Range. This timeline allows you to bounce out any pre-defined range, which is great for mixing live albums, or exporting a portion of a mix as a clip or preview.

Tracks in the Editor window are laid out in the standard fashion. The left side of the window can display the currently selected channel strip, making work on all aspects of one particular track very easy. The right side of the window displays all session lists at a glance, such as tracks, busses, regions, snapshots, groups, etc.

The other main window is the Mixer window. While there is quite a bit of flexibility in setup and routing, there is also a designated signal flow that is used: channels feed into subgroups, which in turn feed the main mix, like on a console.

Harrison gives you an unlimited number of audio, MIDI, and auxiliary tracks, which then feed into a possible 12 subgroups and/or the main stereo bus. The 12 subgroups are designed to act as submixes or time-based effects tracks. Harrison automatically accounts for the latency of all tracks feeding towards the submixes, and ultimately the stereo bus as well. Should you need additional aux tracks for submixing or time-based effects, you must account for any incurred latency on your own. In practice, I only did this when a track needed extra little reverbs and delays. Any latency here was either unnoticeable or didn’t affect the audio in any negative way.

The left side of the mixer window displays lists of channel strips, groups, and user-favorite plugins. The right side of the window displays the 12 subgroups, the main stereo group, and the monitor section (more on that later).

The setup of how the busses are fed by the tracks in Mixbus is interesting. Whereas most analog consoles have group assignments and aux sends, those have more or less been combined here to feed the 12 mix busses. Amount of, and stereo placement of each feed, are fully adjustable.

The layout and look of tracks in Mixbus feels closer to an analog console than any other DAW I have used or seen. Every channel has bus assignments and a 4-band semi-parametric EQ that are always on display. They are relatively easy to use, but take up a lot of real estate and cannot be hidden. Again, the EQ is part of the console feel and sound that Harrison is going after. Each channel also has an input trim (THANK YOU!), mute and solo buttons, a fader and dynamics section. The onboard dynamics processor can be set to Leveler (low ratio with adjustable attack time), Compressor (adjustable ratio, fixed attack and release), or Limiter (with adjustable release time). While basic in scope, the dynamic section does a decent job when nothing special is needed other than basic dynamic range control.

At the top of every track is a small, useful window that toggles between signal flow order, or controls for that channel. Controls include: record arm, input and output routing, polarity, VCA group assignment, as well as solo lock and solo isolate. You can switch between accepting the input signal, or the signal that was previously recorded… just like on a split format console. It’s hard to believe that some DAW manufacturers still don’t have a polarity switch on every channel as a default, so it’s nice to see little touches like that here. Mixbus even has a polarity optimization feature that can analyze multiple audio tracks and offer automatic polarity options that you can toggle between to find the best fit. Elegant and useful.

The signal flow order window is a spot where Mixbus really shines. Every piece of processing (including the fader and onboard EQ/compression), auxiliary sends, and even hardware inserts, can be arranged in absolutely any order. Other DAWs pretty much seem to have processing be post-fader with sends either pre or post. Mixbus gives so much more flexibility than that. I particularly enjoyed expanding drums to reduce bleed, then sending the full dynamic range to reverbs, before riding the fader into the channel compressor.

The 12 mix groups look similar to tracks, but have simplified tonal controls (a defeatable three-band EQ fixed at 300Hz, 800Hz, and 2kHz, in lieu of the parametric EQ and filters available on the channel). Each group also has a saturation control labeled “Drive”. In mixing, I found this tool to be excellent for getting groups of instruments to sit right in the mix. The amount of saturation doesn’t affect the level of the track, and the saturation VU-style meter ends up being useful here as well. Each group has a pan pot and stereo width (fully mono to fully stereo) control for placement in the stereo field. Additionally, each group has the same dynamics processor as the channels, with an added sidechain compressor setting. Each group can use the sidechain, and any channel can feed it, but there is only one sidechain as far as Mixbus is concerned—so any groups using it will all be triggered by the same signals.

The main stereo bus contains the aforementioned controls, along with a few extra features. A look-ahead limiter and phase correlation meter exist at the final output, and while every channel and bus has a standard dBFS digital meter, the stereo bus has a K-14 loudness meter. The K-System meters (designed by Mastering Engineer extraordinaire Bob Katz) is an integrated metering, monitoring, and leveling setup that helps you get consistent loudness results while maintaining a solid dynamic range. Read more about that here.

At the far right of the mixer window is the monitoring section, and I’m a huge fan of it. A dedicated monitor controller or control section, similar to that on a large format console, is paramount to making good mixes, as far as I’m concerned. And the fact that many DAWs offer nothing in regards to that is sad. Apart from letting you know if any channels are solo’ed, muted, or auditioning audio (listening without going through any of the processing or busses—a very cool feature), you have a choice of solo modes: AFL, PFL, or SIP (including solo in front!). Exclusive solo and solo-overrides-mute options are available alongside solo boost level, adjustable dim, mono, polarity, and mute. You can also easily add any plugins to process the monitor feed without affecting the mix. This whole section alone is worth the price of admission and frankly makes mix translation much easier to achieve.

Last in the mixer window are the VCA faders, new to version 4. Mixbus has grouping capabilities for tracks to aid in mixing and editing, similar to other DAWs. However, there are no nested groups (group within a group—a nice feature in Pro Tools). The VCA faders come in very handy here. Any tracks or groups can be controlled by a VCA fader, as well as added to or removed from the VCA faders at any time. In a very nice twist, deleting a VCA fader writes that info to the individual tracks, so no valuable mix info is lost. Additionally, the VCA faders (and the 12 subgroups) have a toggled “spill” feature, which quickly shows only the tracks using that VCA or subgroup.

In Use

Getting a session up and running in Mixbus is easy and should be pretty straightforward for anyone who has used a DAW before. Dragging and importing tracks is easy, as is the hardware and software routing of signals, which features an incredibly useful hardware latency calculator. Initial prompts ask some questions to help with setup (for example: Do you use hardware or software to handle your input monitoring?).

The look of Mixbus is clean and straightforward, but packs a lot of information in. More so than Pro Tools, Mixbus is heavily aided by the use of larger screens, but has very useful scaling features to help maximize screen real estate. I’ve definitely had Pro Tools windows with functions that were offscreen and allowed me no way to reach them.

Though Harrison’s roots are in the analog domain, the digital editing and programming capabilities offered in Mixbus are just as comprehensive as any competing DAW on the market.

Editing audio is also easy and flexible, if not as responsive as Pro Tools on my computer. The user interface here works, but is not as smooth and usable as Pro Tools. Audio regions that overlap are stacked in layers, similar to photo editing software, meaning layers can be moved up or down depending on what you want to hear at that time. A very nice feature, stacked audio tracks can also all be played at the same time, which is great for sound effects or handclaps where you need multiple regions to play back simultaneously, but don’t really need additional audio tracks.

The editing tools and modes in Mixbus are easy to understand and use. However, there is a “smart” tool functionality that combines several modes, and I can’t help but wish it were smarter. As a comparison point, the smart tool in Pro Tools allows me to edit and arrange audio in a much smoother fashion without having to constantly switch tools.

Fades are easy to draw in place, and getting accurate crossfades is simple as the waveform view is translucent. While Mixbus does not have as many fade taper options as Pro Tools, there are multiple choices, and finding one that works was not difficult. Mixbus, by default, actually always fades audio in and out, on every region. This has to do with digital audio and how it exists in an “on or off” state. Automatic crossfades help eliminate little clicks and pops.

A facet I sorely miss about Pro Tools here is the absence of offline, Audio Suite-style processing in place. I use this feature heavily, as tracks I get are often recorded at home and have problems. Applying de-noise, de-click, de-reverb, pitch correction (and creating doubles), phase adjustment, tape saturation, filtering, etc., are staples of my workflow, and I often do a decent amount of clean-up even before mixing starts—so I would love to see this feature added. However, for plugin usage, Mixbus does support AU, VST and LV2 plugins, which opens the field of available processing quite a bit.

Flipping over to the mixer to begin balancing the tracks is where the real magic of Harrison Mixbus comes to light. This is an entirely subjective opinion, but it just sounds better, and I’m underselling that a bit. The way summing is handled just sounds smoother, more musical, and more natural to me. Additionally, like analog gear and even modeled simulations of that gear, you are richly rewarded by good gain-staging and mixing habits overall.

Mixbus itself has a sonic fingerprint, and like a console, can be driven to obtain different shades. The metering, both individual channel meters, and the K-14 on the mix bus, guides mixers to that sweet zone where everything really gels together. It’s a different, more holistic experience than Pro Tools, and I love it.

Mixbus has made mixing itself a more fun and engaging experience. Using just faders, and built-in filters and EQ (not surgical, but very musical), felt quite a bit like mixing on an actual analog console. The user interface translates very well here, and so did my mixes because of that. Absolute A+ for sound quality.

Bouncing a mix is very easy, flexible and powerful. You can bounce out multiple formats, time ranges and stems simultaneously. Exports also give a very informative visual analysis report that shows LUFS, LU (Loudness Unit) histogram and range, waveform display with peak indicators, and a spectrogram view.

Sadly, MP3 and AAC, two of the more popular formats for sharing and listening to rough mixes with artists, are not supported here. Licensing is required for Harrison to use those formats, which would drive up the (very competitive) price of Mixbus. However there is an included full-fledged metadata editor.

To Be Critical

There are, however, a few areas where Mixbus could use improvement. Implementation of full stereo functionality is lacking to me. I noticed that while the busses to the 12 stereo subgroups have full panning and balance flexibility, auxiliary sends (just like the ones in Pro Tools) appeared to be mono-only, whether they are feeding a mono or stereo aux bus. This means if I use an aux send to feed an aux bus, I can’t pan the guitar left and the reverb send right. This is a minor complaint and affects few situations, but I like to experiment when mixing and need flexibility to try whatever options pop into my head. Harrison later noted that this is in fact a bug which will be fixed in version 4.3.

That said, I do feel full stereo functionality is lacking with respect to plugins, as Mixbus does not offer multi-mono capabilities—something I use all the time in Pro Tools to de-correlate my delays and reverbs. This same limitation applies to the aforementioned “stacked layers” as well.

As mentioned above, the editing and arranging functionality just doesn’t quite feel as smooth and easy to operate as it does in Pro Tools. Navigating, selecting and cutting between any two exact points is just faster and easier in Pro Tools. For example, two mono audio tracks cannot just be dragged onto a stereo track to combine them (and vice versa); the tracks must be imported in the right order and manner for them to become a true stereo track. This isn’t a deal breaker, but all of these functions need to be smooth and seamless to accommodate modern users whose methods are as diverse as the genres they create in.

Selecting and navigating in and around the timeline also feels slightly limited compared to Pro Tools. Keep in mind that I have been a near-daily user of Pro Tools for well over a decade, and many of my workarounds have become second nature. I have noticed that time and repetition have made improvements to my workflow here.

Additionally, the tracks, subgroups, and main stereo bus are all in the same window, and there is no way to separate them. If viewing all 12 subgroups and the master bus, I can see only two audio tracks on my laptop screen, making navigating within the session laborious. Tracks and busses can be shown or hidden as needed, but that means more time is spent scrolling and clicking, which takes away from what should be a seamless process. Offering the mix busses as a separate window would ease this issue, and much more successfully utilize multiscreen setups as well.

One of my biggest pet peeves about working in Mixbus though, is the lack of any way to import data from another session. Users can save templates, but I love the ability to think back on a session that had something I need and seamlessly import that into the current session. The ”Import Session Data” feature set in Pro Tools is sorely missed here.

Lastly, I feel the user manual, while greatly improved from the initial versions I saw, still needs some work in regard to clarity and scope. Several features are mentioned by name, but then never again revisited or expanded upon in any way. However, Harrison has provided explanations of many of the features in a series of informative streaming videos. This has become more and more the norm in recent years, but I still prefer a fully functioning PDF. Solving an issue with clients in the room via written manual looks professional. Watching videos while they wonder why they hired me does not. Also, videos cannot be updated the same way an in-depth and accurate user manual can. In all fairness, I think many companies have these same issues.

Summing it Up

As mentioned above, adopting an entirely new DAW is a daunting task. Dedicated users will be looking at a steep learning curve, and will have to get comfortable being uncomfortable for some time. However, there are benefits to having a secondary DAW in your setup, and anyone who has ever had their current DAW glitch or fail knows this intimately. Although I will keep and use Pro Tools for tracking, editing, and sharing audio with other users, I’m also going to continue to mix using Mixbus. Ultimately, how it sounds is of paramount importance and Harrison has really nailed that here.

Another concept to consider is the size of DAW manufacturer, the pros and cons that brings, and thus the level of customer service offered. While I, along with other Mixbus users, may have some complaints about the functionality in some areas of the software, I know for a fact that others have written in to say they still prefer to work with Harrison over some better-known companies. I know that because of my lengthy correspondence with some of the fine folks at Harrison.

The last page of the manual has contact info—an email address and a phone number that a person actually answers. Also, staff members are on the Mixbus forums, and are not only forthright and honest, but actually listen to their users. Smaller companies tend to do this better. Anyone who has encountered the Minotaur on the Avid or Logic website while attempting to get help knows exactly the value in this.

I’ve now been working within Mixbus since early version 3, and have seen Harrison’s commitment to evolving and continually improving Mixbus. If you have found yourself unhappy with the sound of your DAW and want to try something new, I highly recommend giving Mixbus a try. The standard version retails for $79, with Mixbus 32C retailing for $299.

Please note: When you buy products through links on this page, we may earn an affiliate commission.

Mike Levine

January 18, 2018 at 10:07 am (7 years ago)Test