The Pioneers of Audio Engineering: Les Paul

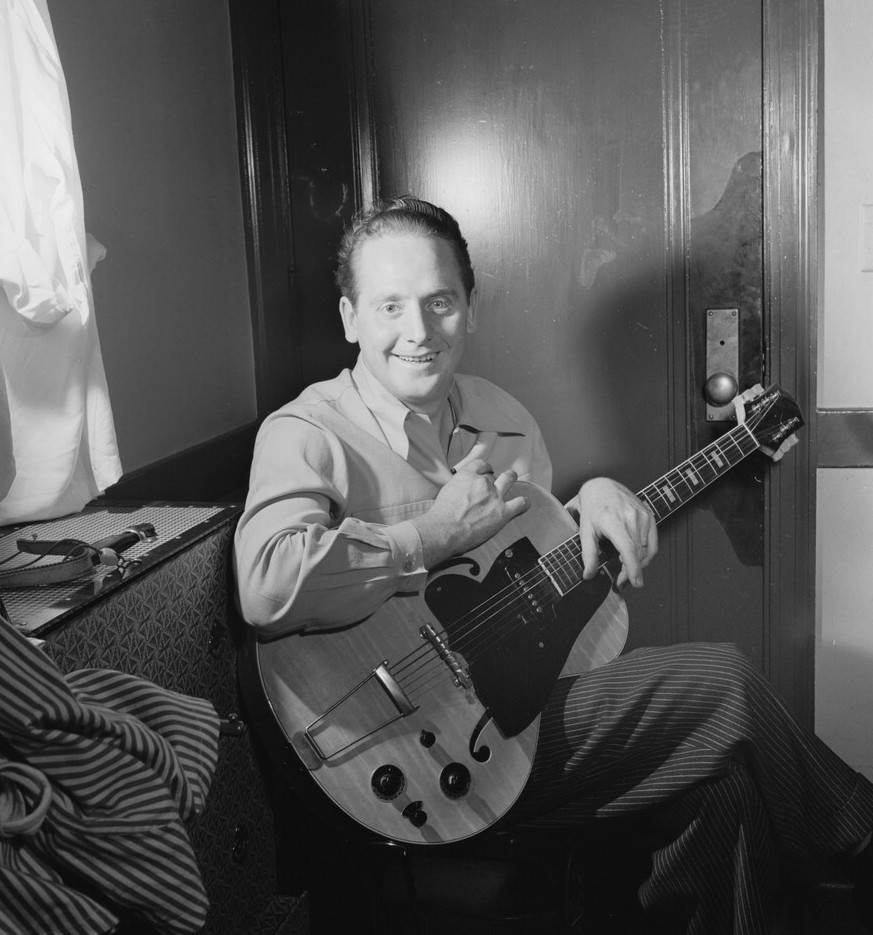

Les Paul, pictured here toward the end of his life, never gave up designing, tinkering, and performing until the very end.

Who was Les Paul? He was man who could be classified in many different ways: Inventor, audio engineer, producer, arranger, musician—as a jazz, country and blues guitarist—and designer of audio circuits and guitars.

As disparate as each of these skills may be, he brought one common quality to all of them: Innovation. It is remarkable to recognize just how many of the innovations we now take for granted in audio can be traced back to this one man.

As I was doing research on his life, I couldn’t help but be overwhelmed with a feeling of sadness at times. Sadness because I’ll never get to meet Les Paul, sadness because I fear the world is lacking in people as great and as significant as him anymore.

Les Paul was a person filled with new ideas, exuberance, and a seemingly unquenchable thirst for life. He saw the world like a collection of small puzzles and seemed to genuinely believe that he was put on this earth to solve all of them.

His inventing started from an early age when it became clear to him that a “normal” harmonica holder just wasn’t good enough, and he didn’t stop for the rest of his life. He was at it even as he approached 90, working to improve the hearing aids he had to rely on late in life.

Sadly, he did not get to complete that endeavor, passing away in 2009, with less-than-innovative hearing aids to contend with. But along with the sadness I feel for a world without Les Paul is an awe of his accomplishments, and a gratefulness that he was even here to change the face of music and audio production as we know it.

An Unordinary Life

Les Paul posing with part of his guitar collection in a photo from the Les Paul Foundation website.

Paul began his musical career playing country and eventually, ended up in jazz and popular music.

He is one of the pioneers of the solid body electric guitar and experimented with various configurations for years until finally teaming up with Gibson to form one of the most successful and long-lasting endorsement partnerships in music history.

Les was never quite satisfied with the “typical” anything. When something he thought up wasn’t available, he would create it. He is credited with being one of the first to experiment with many different recording innovations such as overdubbing, delay effects, phasing, and many more.

He was also one of the earliest home recordists, and was recording his trio in his apartment in Chicago as early as 1935. He would record his then-wife and constant collaborator, Mary Ford, all over his house, and even displayed his sound on sound technique live using Ampex tape machines on the Alistair Cooke’s “Omnibus” show. He appeared on the show in order to dispel rumors that the sole basis of his music was electronics, rather than human performance.

I was fortunate to get my hands on a copy of his autobiography Les Paul: In His Own Words, which released the same year of his death. The book is no longer distributed to stores or online retailers, but with a little digging you can still find it second-hand or on the Les Paul Foundation website. Throughout this article, I’ll include key quotes from the book to help tell Les’ story in his own words.

Early Life

Lester William Polsfuss was born in 1915 in Waukesha, Wisconsin. His parents, George and Evelyn Polsfuss, were of German ancestry. They divorced when Paul was still young, and so he was raised primarily by his mother.

He showed his exuberance and inventive spirit from a very young age, even modifying his mother’s player piano as early as 8 years old. He would cover up the holes on the piano roll and make new holes to alter the compositions to his own liking. This was typical of Les. It was almost as if he couldn’t look at anything without wondering how it worked and how he could change it to make it better.

“When I threw the switch, I wanted to know what happened between the switch and the bulb that made it come on. I knew there was something going on there and I wanted to know in detail what the hell it was.”

Les was given his first harmonica by a ditch digger around the same time he was altering his mother’s piano roll. That harmonica truly jump-started his love affair with music, which would last the rest of his life.

After designing his own neck worn harmonica holder—which allowed him to play both sides without removing it from the holder—he began to also take an interest in electronics. He started by building a crystal radio set and going to the radio transmitter tower on weekends where he introduced himself to a friendly engineer who would show him the equipment and answer any questions he had.

From here, he complimented his harmonica with a guitar from Sears, and began to play anywhere that had an audience. Les was a born entertainer, and jumped at any opportunity to play in front of people. Soon, he began playing regularly at Beekman’s Barbecue Stand, and it was there that he was confronted with the catalyst that was to spark his obsession with developing an amplified electric guitar, and perfecting it. After finishing one set, he received a note from someone in the audience that simply said, “Red, your voice and harmonica are fine, but your guitar’s not loud enough.”

The Origin of the Les Paul Solid Body Guitar

The instrument that Les Paul would eventually create with Gibson has become one of the most iconic and popular instruments in the history of modern music.

Paul started out with a telephone mouthpiece, but using it on stage created too much feedback. He eventually figured that a phonograph needle might work better so he jammed his dad’s player’s needle down into the guitar’s bridge and connected it to a radio speaker. It wasn’t perfect but it worked.

(This wasn’t the only occasion that he’d try out a solution with whatever he could get his hands on. Around this time, he also had the idea of building his first disc cutting lathe with a Cadillac flywheel and dental belts.)

As a teenager, Les further developed the idea of a low-feedback amplified guitar by creating his first solid body electric using a two foot piece of metal rail from a nearby train line.

“Using a short length of steel railroad rail and two railroad spikes, I invented a device that could give me a consistent reference point for my experiments. I took a guitar string and fastened it at each end of the steel rail using the spikes like a bridge and nut to raise the string so it could be plucked. Then I took a telephone microphone, wired it into Mom’s radio for amplification, and placed it on the rail under the string. I soon figured out that the tremendous solidity of the rail allowed the string’s vibration to sustain for a longer time, and there was no feedback.”

After eventually dropping out of high school with his mother’s blessing, Les teamed up with Sunny Joe Wolverton’s Radio Band and began performing on “hillbilly” radio stations in Missouri. They had some success together and both moved to Missouri to start a two-man act, to which Paul credits his improvement as a guitar player. Sunny Joe became his mentor and Les had a knack for picking up and imitating everything he did.

After his time with Joe ended in 1934, Paul moved to Chicago and adopted a double identity, playing as “Rhubarb Red” on daytime country radio and as “Les Paul” at night, jamming with the jazz greats.

While playing the clubs and touring the country he remained unsatisfied with the electric guitars of the time, and they kept reminding him of the original problems he encountered way back when he was just a kid playing at Beekman’s Barbeque stand. He deemed the few commercially made electric guitars available at the time unacceptable due to their uneven response, as well as buzzing and humming issues. He didn’t find any of the amplifiers suitable, either.

One day when Les had enough, he decided to take matters into his own hands and had a guitar made to specifically meet his demands. He went over to National guitar company and had them build a custom guitar with no F holes. The workers in the factory thought he was crazy, but obliged what seemed like an insane demand. After receiving the finished guitar, he cut out a hole and dropped in his homemade pickups near the bridge, creating one of his first electric guitars.

The Very Beginnings of Multitracking

Paul’s take on the solid-bodied electric guitar wasn’t his only innovation.

In early 1935, he started a trio and began to record in his small apartment, where he would begin his experiments with the “sound on sound” techniques we take for granted today, pushing the limits of the technology available.

At first, he started with very humble equipment:

“My recording machinery was behind a folding bed, so to record, we’d fold the bed down and crowd around it,” he revealed in his autobiography “I’d sit on the edge of the bed where I could reach the recording controls, and there was just enough room left for Ernie and his bass, Jimmy and his guitar, and my dog. Using the homemade recording machine I’d built, a disk cutter, we would record our songs and then play them back.”

His multitrack breakthrough came one day after rehearsal when he wanted to record a song, but his band had already left. The idea struck him to add a second playback arm and cut the track twice on two different sets of grooves.

The hard part was having to start both arms at the same time so they would sync up. It was very crude version of what we now know as multitrack recording, but it worked, and he was able to overdub himself on a different set of grooves and play them back in sync. He no longer needed his band to make a record. Eventually, after refining it years later, this breakthrough idea would change Les Paul’s life forever.

The Solid Body Guitar Evolves

After leaving Chicago for New York in 1938, Paul landed a major gig with a featured spot on the Fred Waring’s Pennsylvanians radio show. It was here that he was able to bring the sound of the electric guitar to people all over the country.

Fred Waring had specifically picked Paul to play electric guitar rather than acoustic guitar because he felt it was a sound that almost no one had heard before, and would help set him apart from the other bands that were playing on the radio at the time. For many, the Pennsylvanians radio show would be the first time they’d ever hear the electric guitar—and it was being played by none other than Mr. Les Paul.

By this time, Les had been experimenting with electric guitar for many years. The main guitar he had been using while playing back in New York was his “Gibson Cheapie”—an L-50 model with a chunk cut out and another one of his home made pickups dropped in.

Les Paul shows off his original “Log” concept for the solid body electric guitar. He used a single dense piece of wood, flanked by a pair of cosmetic “wings”, allowing him to get sustain and without feedback, all while keeping the appearance of a more conventional guitar.

Although Paul enjoyed playing this guitar, he was always looking to improve on his designs. He had been intrigued with his early experiment using a steel rail with one string, and long remembered how well that string had vibrated and sustained.

He eventually realized it was the solidity of the neck and body that were critical factors in providing that sustain. Now, he just had to figure out how to get something as solid as a steel rail into a guitar in a practical way.

Les was friendly with guitar maker Epi Stathopoulo and was eventually granted access to the Epiphone factory, where he was allowed to use the equipment on Sundays. There, Paul took an Epiphone neck, a length of pine for a makeshift body, and mounted his homemade pickups into the wood. This became his legendary guitar, known affectionately as “The Log.”

This same guitar was used to first demonstrate his solid body design to the Gibson guitar company that he would later partner with. But at first it didn’t take. The Log wasn’t only initially rejected by Gibson, but Les remembers them laughing at him and calling him “the character with the broomstick with pickups on it.” It would be ten more years before the company would finally team up with him to create one of the most iconic instruments of all time.

Going to California

In 1941, after making “The Log” and despite being rejected by Gibson, Les still wanted to fulfill his lifelong dream of playing with Bing Crosby, and he acted on that by making his way out to California where his dream would be made a reality.

While in California, he started a new trio before being drafted into the military. He was lucky enough to secure a job for the army producing radio shows which would be broadcasted worldwide to entertain the troops. He would take pre-recorded clips from different sources and cut them together to form a variety show of his own making. He credits this work with helping him learn much about disk editing, which later proved useful when operating his own studio.

An early German “Magnetophon” that inspired the Ampex line that Les Paul would help to develop and promote in the U.S.

During his time in the service, Paul came to recognize that the Germans had superior sound recording and reproduction technology at their disposal.

It wasn’t until after World War II had ended that the Allies discovered that the Germans had been using the first magnetic tape machines, which they called “Magnetophons”.

They had figured out that with magnetic tape, the quality of the recording was better from the start, and that, unlike with discs, that quality did not lessen as the length of the recording increased.

While riding down Sunset Boulevard after the war with his hero Bing Crosby, Bing tried to persuade Les to create a new studio to record his music and educate others. Paul initially shrugged the idea off, but then went home and sealed the garage door, threw some rugs down and paneled it with transite insulation. He sealed just about everything except the side window, which he used as an entrance.

As noted in the previous part of the “Pioneers of Audio Engineering” series, on Tom Dowd, recording studios around this time tended to present a very sterile and conservative environment. Engineers were taught specific ways to execute each task and usually weren’t allowed to deviate too much from that standard. Les Paul solved this problem by building his own studio so he wouldn’t have to answer to anyone but his audience, and would be able to experiment and record the ways he wanted.

According to his autobiography, he spent $1,000 on his new garage studio in 1945. (Somewhere in the neighborhood of $14,000 today.) He did not charge anyone to record there for the first three months, as he was mainly experimenting and figuring out his approach and getting familiar with his equipment and room.

For the first time ever, it was possible for Les to write, produce, arrange and perform a song entirely on his own. Les Paul was doing this over 70 years ago, at a time when doing everything yourself was unfathomable. “I was doing everything myself, right down to delivering the masters to the label,” he remembered. He was a pioneer of the independent home based recording culture, except instead of just having to buy a Focusrite Scarlett interface and downloading a copy of Reaper, he had to build an actual studio from the ground up, including all of the equipment and electronics.

In his autobiography, Paul talks about the musicians who passed through and recorded in his garage, including Bing Crosby, The Andrews Sisters, Art Tatum, Tex Williams, Pee Wee Hunt, Gene Autry, and even W. C. fields, whose only audio recording was done right in Les Paul’s garage. Bing Crosby’s wife brought over his four kids to record a Father’s Day’ surprise recording. Les even talks about hanging out in his backyard with Leo Fender and Paul Bigsby. I can only imagine what nights with these three guitar design legends hanging out and talking shop might be like.

Mary Ford, and Making Multi-Track Magic

Les had needed a country singer to fill up shows on NBC when he was introduced to Colleen Summers, now better known by her stage name, Mary Ford. Les and Mary hit it off right away and soon started dating.

After months of trial and error, Les had developed a way of capturing multiple tracks on one disk while making sure the line noise didn’t increase to the point it would be unusable. His home studio had paid off significantly, he was now able to achieve a special sound that no one else could get.

Once he established his sound on sound technique, he realized there was one more important element he could now add: Controlled delay. He didn’t want a concert hall reverb style over reverb anyway, because he felt it muddied up the sound. And he realized that an extra playback cartridge directly next to the recording head would allow him to achieve a delay that would be based on the placement of the head. You could move the head back to make it delay longer. It is one of the earliest instances of slapback delay being used.

This was a time of intense experimentation for Paul. In 1948, he released “Lover,” the first track he finished employing his “New Sound” a year earlier and using the multilayer techniques he had long been experimenting with.

Les Paul and Mary Ford produced a string of major hits together in the early 1950s including “How High the Moon”.

“You’d lay your first track down on a disk, then listen back and play something along with it while you used the second machine to record the combined sound on a second disk. You repeated that step as many times as it took, discarding one disk after another until you got those first two tracks blended just right.”

Each new track would cause the previous track to lose fidelity, so the most important tracks needed to be done last. When making “Lover,” Paul attempted to combine all of his inventions and techniques together, from his super-hot guitar pickups, to varied disk speeds, to specialized playing techniques.

The track ended up being 8 layers deep, the first of them being a percussion pass with just a snare and cymbal. When Les didn’t direct inject his guitar right into his desk he would use a Fender amp modified with a Lansing speaker. “Lover” was the epitome of what became known as his “New Sound.”

A Gift from Bing

Les Paul’s earliest multitrack innovations used disk technology. But not for long.

When Germany was finally defeated and the Allied forces took over Germany’s research facilities, two Signal Corp officers were assigned to investigate the communications technology: Richard Ranger and Jack Mullen.

Their investigation led to the discovery of the Magnetophone, the first ever magnetic tape machine, invented by the German military. Mullen would eventually go on to work with Ampex and take this innovation to America and the rest of the world.

Up until this point, everyone in the U.S.—including Les Paul—was using discs to record their music. Les was introduced to the German machine by Colonel Richard Ranger, and when he saw it, he knew right away this would be great for his old pal Bing Crosby.

Crosby had just left NBC because they wouldn’t allow him to pre-record his shows, due to the inferior quality of disc recordings compared to live broadcast. ABC had agreed to let him pre-record shows, but the quality was still an issue. Paul, being aware of this problem, gave Crosby a call and told him about these new magnetic tape machines that would allow him to finally record clean audio.

After hearing of these new tape machines, Crosby set up a test recording with Jack Mullin, who now was working with Ampex. Mullin brought down his Magnetophons and recorded the same show on both tape and to disk. When the two recordings were compared back to back, there was no contest: Tape was the future.

After hearing how great tape machines sounded, Crosby was convinced, and personally went to Ampex to lay a check down on the president’s desk for $50,000. (Nearly $700,000 today.)

Six months from the time Crosby laid the check down, the first Ampex model 200 was delivered to ABC and put to use in 1947, replacing the original Magnetophons that he had used during the A/B tests.

Crosby remained grateful for the tip from Paul. One day in July of 1949, he pulled up outside of Les Paul’s house with a brand new Model 300 Ampex tape machine.

“So we went out to Bing’s Cadillac, and when he went to the trunk, I was expecting to see a Philco radio or a set of golf clubs. I had no idea what he was up to until he raised the lid, and Holy Christ, there sat one of the first Ampex Model 300 tape machines. And he said, This is yours, for what you’ve done for me.’

After receiving the tape recorder from Crosby, it sat in his studio unused because he didn’t yet know how to do his sound on sound recording technique with his new tape machine. Then, out of nowhere it hit him: The crucial piece that was missing was an additional fourth head.

He drew out a design, called Ampex, and told them that the head in his machine had broken and that he needed a spare, as he was wary of letting them know exactly what he was up to. Mary and he were on their way to a gig in Chicago so he had the head sent to their hotel.

When he arrived in Chicago, the playback head was waiting for him and he hired a worker to drill the holes.

“And that was it. We had sound on sound. My idea worked great, just like I thought it would.”

The Gibson Les Paul

A lot of guitarists have heard the story of the Gibson staff laughing at Les when he brought in his “Log” guitar, but most don’t know that there’s more to the story: Despite the rejection, Les stayed close with the people at Gibson over the years and remained a fan of the brand.

Leo Fender, who you could often find at Les’ house hanging out, came over to ask Les if he wanted to form a partnership and start making a “Fender Les Paul.” According to Les, Fender wanted to join up and go into making solid body guitars together, but Les politely declined because of his longstanding relationship with Gibson. So Fender went ahead without him.

Later, Paul Bigsby brought over one of Leo Fender’s early prototypes for his new solidbody guitar line, and that’s when Les ended up hopping a plane to Chicago with his Log and Leo’s prototype in hand to meet with Mr. M.H. Berlin, head of Chicago Musical Instruments Company, which owned Gibson at the time. Paul had told Berlin about what Leo Fender was planning on, and Gibson finally decided to make a solid body guitar of its own in order to compete.

It struck me as a bit off that Les actually took Leo’s prototype to Gibson, which, at the time, would have been a direct competitor. I’m not exactly sure how ethical of a move it was, or if Leo ever knew or held any animosity towards Les about it. In any event, he would likely have been able to convince Gibson sooner or later, and the competition between the two companies has brought us two amazing styles of electric guitars, with Fender developing the first commercially-available solid body and Gibson working to one-up them.

The Golden Years

Les Paul with his wife and collaborator, Mary Ford at near the height of their chart-topping success as pop recording artists.

The early 1950s were a particularly successful time for Les Paul. By 1952, he had his own signature model guitar with Gibson.

In 1953, he started doing a television show called Les Paul and Mary Ford at Home, and the pair went on to record a string of major hits, including “How High The Moon” and “Tiger Rag”, using the sound on sound techniques he had developed for disk recording.

Les and Mary had moved to Mahwah, New Jersey to be closer to their production company. They built the house into the side of one of the Ramapo Mountains, less than an hour drive from NYC. He even had a big hole gouged out of the granite behind his house, which he turned into an echo chamber.

While filming the TV show, Les got the idea for the first multitrack recorder: Working with film audio inspired him to want to build an eight track machine where the heads were all evenly aligned, one on top of the other, in what was called “sel-sync”. This allowed you to use the same head for recording and playing back so that everything would remain in sync while overdubbing.

Ampex worked on creating a new eight track model for about a year, delivering the prototype to New Jersey with a bill for $14,000. (Nearly $140,000 today.) Paul was disappointed however, and felt there were many problems that still needed to be addressed.

The whole thing wasn’t really functional until about 1957, when they redesigned the machine with Paul’s own pick for a designer, Rein Narma, who is also known for designing a pretty famous compressor that you may have heard of—the Fairchild 660/670. (Ampex admired his work so much they even hired him.)

The Final Years

Although Mary and Les eventually divorced, and she remarried, they still talked frequently. Les remembers speaking with her for the very last time in 1977 in which they even talk about the possibility of getting their act back together. She passed away September 30, 1977.

Les kept on playing music, innovating and inventing until the day he died. Despite a long-broken and disabled arm that he had set into playing position, and age-related hearing loss, he never dreamed of stopping. He kept a residency at the Iridium Jazz Club in NYC where he played every Monday night for many years, and lived out the rest of his life in the house in Mahwah that he had built and lived in with Mary.

Les Paul was truly one of a kind, and his impact on the music and recording industries has been imprinted on every musician that came after him. He has inspired millions of musicians, and will continue to do so for many more generations to come.

There aren’t many people that will make as much of an impact on the music world as Les Paul did. Every one of us who records music or enjoys making it should be eternally grateful for Les Paul and the trail he blazed ahead of us.

David Silverstein is an audio engineer who works at Sabella Studios. You can find more of his writing on his blog, Audio Hertz.

Please note: When you buy products through links on this page, we may earn an affiliate commission.

robertm2000

December 7, 2017 at 8:01 pm (7 years ago)Les Paul – he was THE innovator in sound recording. I can’t help wondering where the record industry would be if Les Paul hadn’t come along. Maybe setting up a row of single track tape recorders, all synced up electrically?

L.A. Nights

December 8, 2017 at 5:58 am (7 years ago)Les Paul passed away in 2009.

David Silverstein

December 8, 2017 at 10:01 am (7 years ago)Yes, good catch. I’ll make sure we update that.