How to Properly “Vintagify” Your Own Tracks and Loops

This is a post by Mark Marshall. For more detail on getting authentic-sounding vintage tones, try his new full-length course, Producing and Recording Electric Guitar.

Clearing samples for use in music has become not only a complicated legal process, but an expensive one. So what happens when your production depends on the implantation of “old” sounds?

Taking a chance on not clearing a sample is not always an option if you want to be sure to you can get your track out there (or actually make any money on it.) So why not just take the time to create your own retro samples? They’ll be yours to own. No legal issues. No future conflict. And they’ll be 100% unique to your track.

To help you create even more convincing retro samples, we’re going to go through some failsafe steps I use to create convincingly old-sounding samples for my own productions. You’ll even get to hear some before-and-afters below.

Boom Boom Boom

When re-creating drum sounds from old records, it’s good to keep in mind the sort of mic’ing that was common in that time period.

For instance, in the 1950s and early 1960s they didn’t use many mics on the drums. Often, there was only one overhead mic. Eventually, a bass drum mic was added, and then, a snare mic started to become more common. So, if we really want a vintage vibe, we need to not over-produce the drum kit.

Whether you’re recording live instruments, or starting with sampled ones, this process remains the same.

For this example, I’m going to use the EZDrummer Funk Masters kit to create some retro drums.

So many drum samples have been created from Clyde Stubblefield’s drumming. Toontrack actually had Clyde come in to record some of his grooves and sample his drums. So, it’s a fitting place to start.

I’m going to keep the feel pretty loose in this sample to give you a sense for just how “human” you can go, but it can be tightened up or relaxed further.

Tuning also plays a huge role in achieving the tones from this period. As an example, the toms were often higher pitched and more open than what a lot of modern drummers expect. If you’re using a real drum kit to generate your own samples, you’ll have to spend some time to study the tunings of the era you’re recreating. Using a vintage kit alone won’t just get you there.

When using a program like EZDrummer, I’ll often make a few adjustments right off the bat. In the case of getting a retro 50s or 60s drum sound, I’ll begin by pulling down all mics except for the overheads. Let’s just start with these. We may or may not bring in the bass drum mic or a snare mic later, depending on how vintage we’re trying to go.

When starting with the overhead mics in a sample-based program like this one, you may have to adjust the volume of the cymbals. Fortunately, unlike with recording live drums (where you may have to lecture the drummer about how hard he’s hitting each piece in the kit) doing that is easy in a program like this one: Each drum and cymbal volume can be independently adjusted.

Alternately, if you’re recording drums from scratch, you have the option of moving a single mic around the kit until the balance sounds just right—a favorite technique of Daptone producer Gabe Roth.

If I feel like I need a little more body in the snare or bass drum, I’ll add a little of that mic in. The overhead mic is the star though. You can see the image above for the balance I settled on in this example. (I did turn down the volume of the cymbals in the overheads.)

After I had a good drum balance happening, I knew I wanted to put a classic compressor on the drum bus. I like the UAD Fairchild 670 or 660. We’re not looking to completely squish the drums. A little compression will do. We’re not just looking for dynamic range control here, rather, the vintage flavor that specific compressor adds.

Roll of Tape

The most important part of emulating vintage sounds is getting the instrument and the performance right. But once you have that, a couple passes through tape, and a pass through an analog console can help you get a lot closer still.

Next, we’re going to add some tape plugins. (Yes, I said plugins.)

Depending on which era of drums you’re trying to re-create, the tracks were likely bounced from one tape machine to another. Maybe more than once or twice!

It wasn’t until the late 1960s that engineers had 16 tracks to work with. So in order to make room for new tracks, they often had to bounce (or sum) tracks together along the way. This degraded the quality and added a little more to the noise floor. To really get the essence, we need to re-create that bounced tone, so I’m going to multiple tape plugins here.

First, we’re going to stack a few Studer A800 plugins and leave the noise on. (If you really want to get micro on the subject, be sure to check which type of hum is associated with your preferred sound. The American hum is 60hz and British is 50hz.)

You can also play with the IPS (inches per second) control to experiment with how dark you like the tone. I use 15ips most of the time. However, for really retro sampling, I sometimes use 7.5ips on multiple tape machines.

Let’s consider the chain instruments used to be recorded in: Microphone, mic pre, tape, console, bounced to tape, mixed through mixing console, and then captured back on tape in the mix. For this example, I’ve created a somewhat similar signal chain: Tape, Console, Tape.

This is a process I use often for recreating 60s-style sounds. Though I only used two passes of tape in these examples, you could add more tape plugins to further simulate the degradation of bouncing tracks.

Let’s have a listen, in and out of context. For this quick rough mix, I’ll keep the drums a little cranked up to help keep the focus on them.

We could probably tighten the “lock” between the drummer and the rest of the band here by editing the performance slightly, and get an even more authentic sound that way. (Maybe by making that snare drum hit a little earlier on bars 4 & 8, and improving the timing of the fill.)

We could also try swapping out snare drums on the fly to get an even better match for the tone of the guitars. Fortunately, these are things that are very easy to do with sampled drums!

Guitars

Let’s move on to the guitars, which is much more my personal area of expertise, and hear what’s going on more closely. The guitar sounds here feel very authentic to me, and a lot of that has to do with getting the instruments and the amps right.

Although Strats and Tele’s were around and were popular in the 50s and 60s, I really like semi-hollowbody guitars for convincing 1960s soul and funk sample-making. Motown and James Brown guitarists frequently used hollowbody or semi-hollowbody guitars in their tracks.

In these examples, which we’ll hear in isolation in a minute, I used a Gibson ES335 with humbuckers. With this kind of guitar, there tends to be a little more “woodienes” to the sound than with Fenders or solid body Gibsons

Amps

Clean is clean… Or is it?

The truth is that not all clean sounds are equal. A lot of sounds we associate with the “clean” from the 50s or 60s actually had a little overdrive from the amp.

Let’s take the clean sounds of the legendary Stax Records session guitarist, Steve Cropper, as an example. He played with the likes of Booker T., Otis Redding, Sam & Dave, and The Blues Brothers, and he regularly played through a tweed Fender Harvard. His sound had just a little “hair” on it, simply from turning the volume of the amp up.

A lot of the amps used on the sessions of that time were of lower wattage. So even when they were playing them “clean”, the volume they needed to compete with the drums usually induced some subtle power tube saturation. (The one exception to this were direct recorded guitars from that era, though even these often had a bit of saturation from tube and tape components.)

If you have access to a small tweed amp, that is an excellent route to go. The natural midrange in their design is a great pairing for the style of this era. Otherwise, you might want to try other lower wattage amps and turning the amp up to about 4.

This approach remains the same with the vast majority of amp sims, which have sought to mimic this kind of natural tube response. So, analog or digital, keep an eye on that amp volume knob!

Amp Mics

These days, I see a lot of engineers place mics right on the grill of guitar amps by default. That’s a shame, because there are so many good ways to mic an amp. Personally, I’ve never really had a standard of placement for guitar amps. It changes depending on the kind of sound I’m trying to capture.

The distance of the mic from the amp has changed by the decade. In the 50s, it wasn’t even common to have a spot mic on the guitar amp at all. When spot mic’ing eventually became a thing, it was common to see them about a foot away from the amp, to better capture what the amp really sounded like in the room. All of the guitars on early Beatles records for instance, relied on a tube condenser about a foot away from the speaker cone.

In order to create vintage guitar sounds, we need to think about our mic distance too. Putting a mic right on the grill just isn’t going to get you an authentic early 60s tone. In this example, you can hear a Gibson ES335 into a Henry Amps Bad Hombre, mic’d with an AEA A840 a foot back.

If you’re using an amp sim, check to see if it allows you to move the virtual mic on your virtual amp virtually further back. If you don’t have that option, try using a reverb plugin that allows you to effectively re-amp the signal into a room. (The UAD Ocean Way Studios plugin is an especially good option for this.)

As you can hear below, while laying on a vintage signal path helps add more authenticity to the track, getting the instrument, amp, playing style and part right is where so much of the tone comes from:

1960s Bass

Nowadays, we’re all about the big bottom. But back in the day, you couldn’t have too much low end on your record or it would make the needle to jump on your turntable and cause skips. For this reason and others, the amount of low end on recordings was limited.

Until the late 60s (with the notable exception of Motown) bass was often recoded through an amp with a mic. This led to a very round tone. Bassists often favored flat wound strings, rounding things out further still.

One of the most popular amps of the time was a Ampeg B15. it’s a fairly low-wattage bass amp that falls into the “60s clean” (aka “just a little dirty”) category. Ampeg makes a great plugin version that runs in the UAD unison slot so you can take advantage of all the gain staging goodies.

Did I mention that flatwound strings are key to this sound too? They have shorter sustain and the low end isn’t as sub-heavy as what you’ll get from modern roundwound bass strings. As unconventional as flatwounds may seem to modern players, they are a key part of THE soul and Beatles tone. It’s also a great idea to try putting a foam mute under the strings of the bass. This further cuts the sustain of the bass, which is another distinctive characteristic of the time period.

It also makes sense that if you’re going to try to recreate sounds from a certain time period, that you should use EQ’s of that era. I really like Helios EQ’s for 60s flavor. Helios boards were part of the Rolling Stones’ mobile studio, which was used on many a record from the late 60s. If you really wanna go old school, you could also use the UA 610 preamp. It’s the Pet Sounds tone in a box.

In this isolated example, you can hear how much more audible and consistent the bass becomes once it goes through the aging chain, benefitting from a bit of extra saturation, natural compression, and edge.

Piano

Recoding real piano is really challenging in modern times. As many major studios are closing, there are fewer rooms to record nice pianos in. Once a staple of countless middle class homes, today it’s rare that even a smaller recording studio will have a well-maintained piano.

I use Keysacape a lot these days to record real-sounding piano without breaking out a single real mic. It’s actually quite amazing at recreating real piano sounds. I used an upright piano for this next example. To get an authentically “vintage” sounding pop, rock or soul piano, you don’t necessarily want to go for the most impressive and luxorious-sounding solo grand piano in your library.

One tip key here: Contrary to what you may read elsewhere, piano doesn’t always have to be in stereo. For real old school sounds, try mono!

I treated this piano sound with the same channel strip as the others we’ve heard so far: Tape, console, tape.

You can get really deep in Keyscape. There are countless options to tweak, including things as minute as pedal noise, which can add a more organic texture to your samples.

80s Guitar

For the electric guitar in this next example, I took a more of a 1980s approach. This sample features a DI guitar tone with a very fast delay on it to create a doubling effect. This was a popular technique of the time. You can also use a flanger for an 80s-approved doubling effect with a different flavor.

Rhodes

In this next sample, I’m using the Keyscape LA Custom Retro Trem. They didn’t just meticulously sample piano—they samples a lot of classic keyboard instruments.

I didn’t really change anything about the preset in this case. Sometimes, you don’t have to. I simply added my vintage channel strip to the equation.

At the end, let’s hear a rough sketch of how these homemade loops might stack over a simple drum beat and serve as the basis for a new sample-based production.

Synths

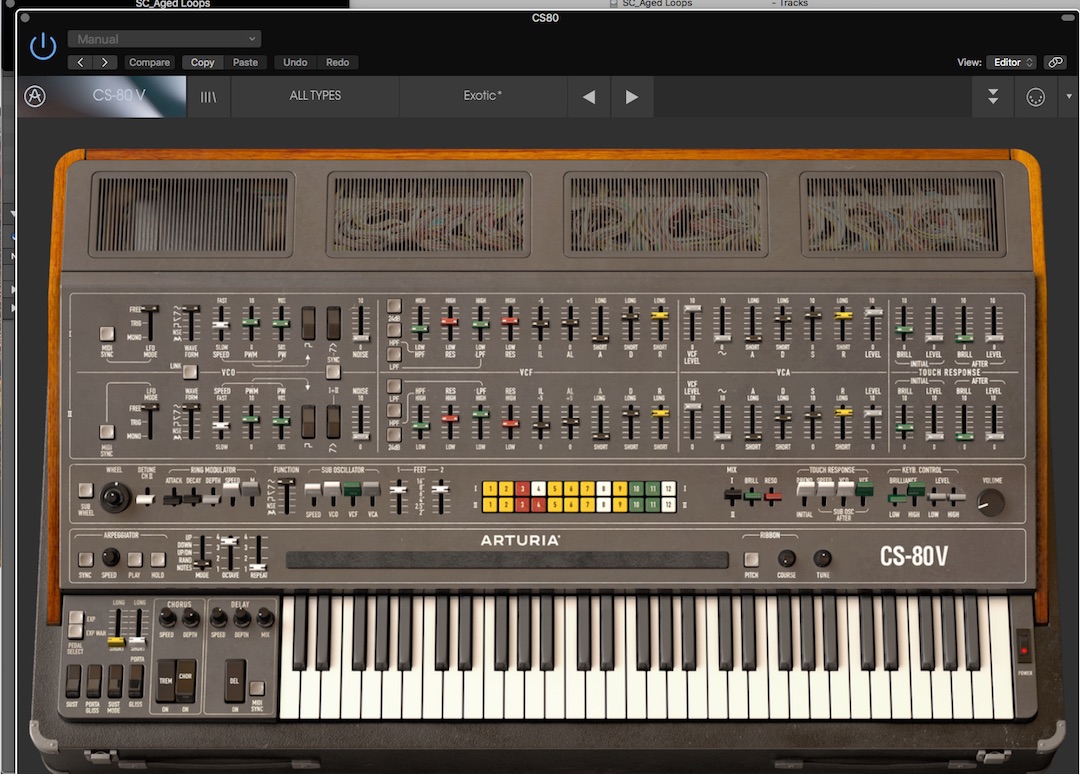

In this next example, I used some Arturia synths from their V Collection. These synths sound great right off the bat. Easily the most accurate emulations I’ve heard.

But there’s one thing about 1980s synth sounds that may be missing: In practice, these synths were often heavily processed. The synth sounds that we most associate with the 1980s often had console EQ applied, delay, reverb and compression. They weren’t just captured. They were sculpted.

I’ve seen a lot of people plug in an old Juno 106 only to scratch their head. What you’ll hear is a raw sound compared to the sound of a final recording chain and mixdown from the time. For the first example below, I used the Arturia CS-80 emulation. It’s one of my fav synths and most notably associated with Blade Runner.

Arturia’s emulation of the classic CS-80 comes very close to sounding like a real CS-80. But to sound like a real CS-80 as you might hear it on a major release, further processing may be necessary.

I changed a few spices in our channel strip for the CS-80 example. Tape was still being used in the 1980s as the primary method of recording, so we’re still using the UAD Studer plugins. I did however, experiment with the type of tape being used. I ended up choosing tape with a little more headroom for a cleaner sound.

It’s worth noting that there can be a big difference between tape brands, and I encourage you to flip through them and listen carefully on your own tape plugins.

I also swapped out the console for this sample. Instead of the Helios channel strip, I switched to the SSL, which was very often used on a lot of popular 80s recordings. It seems like a small detail, but you may be surprised to hear how it all adds up.

I also knew I wanted some 80s reverb applied right to the synths. In this case, I used the AMS RMX16 digital reverb. This reverb is all over the 80s! Let’s hear these in isolation, and then over a simple drum loop for some context on how they might be used in a modern sample-based production.

Orchestras

Creating truly authentic sounding orchestra samples is a real road block for many. Thankfully, Spitfire has given some great solutions to those of us who can’t always afford to record real strings. Still, depending on the library you go with, it could be daunting to lean how to create realistic-sounding arrangements or loops.

This is where the Spitfire’s Composer Toolkit series will become your friend. Think of it as a way to jump start writing for string sections sections. For instance, in the Bernard Herrmann library, they give you instrument pairings that he often used in his arrangements. In no time, you can easily start creating some vibey and somewhat familiar-seeming orchestral arrangements.

In this next example, you can hear me using some of the effect articulations they have included in this studio orchestra preset. Spitfire made it about as easy as it can be for you to create orchestra arrangements without a degree in composition. Especially with the Composer Toolkit series.

The averahe beatmaker with some very basic fluency in music theory can get the Bernard Herrmann Library and create some realistic-sounding string samples in a relatively short period of time. Perhaps not as short as sampling a record. But probably a lot shorter than taking the time to actually clear the sample!

Spitfire didn’t attempt to make these string samples sound “vintage” however. To vintagify (fancy new word I just made up) them, I added our old-school channel strip once again: Tape, Helios Channel Strip, Tape.

Here is another example of me using the Spitfire Bernard Hermann Library. These parts were created without too much wrestling. T

he Harp and Celeste pairing is a classic, and is just one of the many preset groupings available. I applied the same vintage channel strip.

Let’s hear them in isolation, and then how they might pair over a drum loop to get some ideas for how they might work as samples in a modern production.

Words

The point in this article was not to fully degrade the quality of the recordings. You could easily use something like Zotope Vinyl (a completely free plugin) to create the sound of a worn record. Instead, I really wanted to try and recreate the sound of what those instruments sounded like when originally recorded and heard as intended. You could of course do additional processing to lower the quality of a track further and make it sound more like worn, sampled vinyl, or a tape cassette that’s been through the washing machine a few times.

At the end of the day, there is no reason that legal obstacles around sampling classic records have to hold you back. Yes, you will need to learn a little more about music composition and production. But, it’s really worth it to own the music you create. You probably don’t want to create a smash hit like the Verve’s “Bitter Sweet Symphony” only to lose all the royalties in the end and wind up nowhere!

Don’t know a C chord from a hole in the wall? You can still use these very same techniques to vintagify modern recordings that are easy to license for sampling—and may even been free to use. In addition to the option of drawing on high-quality commercial sound libraries, a whole slew of totally free-to-sample recordings (both historic and contemporary) are available at outlets like Archive.org, Free Music Archive, Creative Commons Search and more.

Now, get in your time capsule and start creating some vintage loops!

Mark Marshall is a producer, songwriter, session musician and instructor based in NYC. For more detail on getting authentic-sounding vintage guitar tones, try his new full-length course, Producing and Recording Electric Guitar..

Please note: When you buy products through links on this page, we may earn an affiliate commission.

[…] http://sonicscoop.com/2018/05/24/properly-vintagify-tracks-loops/ How to Properly “Vintagify” Your Own Tracks and Loops […]