Remembering Lee “Scratch” Perry: From Studio to Stage to Deep Space

An immersive experience. The groundbreaking producer Lee “Scratch” Perry offered assurances of that in every way – on record, in concert, and simply face-to-face for those who got the opportunity.

Lee “Scratch” Perry was a mesmerizing figure, onstage and in the studio. (Photo credit: David Weiss)

It goes without saying that there never was, and there never will be, anyone remotely like Perry, who passed away on Sunday, August 29th in Lucea, Jamaica. He was 85.

Perry was an otherworldly pioneer in the way he created music. And he was as prolific as he was experimental – his discography covers hundreds of pages, including 70 of his own studio and live albums.

Scratch’s landmark work with Bob Marley & The Wailers was just one part of his incredible accomplishments. Perry is widely recognized as the creator of dub, pumping lucid dream atmospheres deep into reggae. From there, he influenced electronic, dubstep, trip-hop, dancehall and way beyond. Generations of producers, engineers and musicians were entranced by his Black Ark sound, where tons of delay, phase, filters, samples, and assorted studio wizardry elicit equal parts pleasure and paranoia.

Music and Spirit

London-born and raised in Jamaica, reggae great Sidney Mills had long been aware of Lee “Scratch” Perry. Long before he became a musician and 2X Grammy-nominated producer, a young Mills could instantly recognize Perry’s distinct sounds when they played on Kingston jukeboxes or boomed out from sound systems.

“Scratch was spiritual on a musical level,” says Mills, who was Steel Pulse’s keyboardist, musical director, and producer for almost 40 years. “He always had young folks around him, always sharing the wealth and knowledge. He was just gifted. A groundbreaking guy who was really wild and eccentric but also a genius.”

With his propensity for extreme experimentation in the studio, not to mention his personal interactions, Scratch could make you do a triple take. “A lot of people would say that Scratch was crazy but he wasn’t,” Mills observes. “He broke down music on a cellular level that many people don’t understand. You can just hallucinate on his music. It’s a crunching sound which engineers or artists are all trying to do today with plugins – Scratch did that years ago.”

Mills also notes the power of Perry’s words, an alluring element of the producer’s unique powers. “His lyrics, working together with the rhythms, told the story of the life that he lived, and the story of life in Jamaica.”

For a range of extra-illuminating listening, Mills recommends moving from tracks like Perry’s earlier “Disco Devil” to the more advanced “Heavy Voodoo” (featuring Keith Richards). “Those two records were different styles,” he says. “You can hear the old ‘70’s sounds, and then his newer sounds.”

Live Surprises

As impressive as Perry’s studio track record was, he was equally compelling live. I attended as many NYC live shows as I could when he was touring—going strong until age 83!—accompanied onstage by Subatomic Sound System.

Larry McDonald, playing live with Perry and Subatomic Sound System in Brooklyn, 2019. (Photo credit: David Weiss)

Each Lee “Scratch” Perry show I saw was completely unforgettable, yet also seemed to go by in a flash. Perry instantly entranced his audiences, drawing us into his every utterance and movement. He could stand almost still for a whole song and still captivate you, his mystical effect compounded by the band’s huge grooves.

Subatomic Sound’s live rhythms were propelled by master percussionist Larry McDonald, who toured with Scratch for over a decade. Today, McDonald’s credits include Bob Marley, Peter Tosh, Dr. Ernest Ranglin, Gil Scott-Heron, Taj Mahal, Bad Brains, New York City Ska Orchestra, Rocksteady 7, Dub Is A Weapon, and countless others.

Their playing relationship dates all the way back to the early 1960’s, when Perry performed at a Jamaican club where McDonald was in the house band. Nearly 60 years later, the two were still playing together on multiple tours, Perry never failing to captivate McDonald from his prime seat behind the congas.

“His performances were always one of a kind—eccentric and eclectic,” McDonald says. “It might appear to be gibberish that he’s talking, but he’s actually speaking Jamaicanese and most of it means something.

“Everyone in the band had to stay on their toes. He’ll change something in the middle of the song, and you don’t want to miss it. Some nights it gets so intense, you just get totally into it. You do get into some kind of trancelike mode, and you don’t even realize how much time has gone by. He would be onstage for three hours if you let him.”

The Dub Source

McDonald notes Perry’s groundbreaking role in reggae. “If there were no Lee Perry, I can’t say for sure that there would be a music called dub,” he says. “Lee’s stuff was always different from the mainstream. One time when I was in the studio with him, I was rocking a mic stand base around on a riser, and it was making this weird sound. He put a mic on it! Little stuff like that was what made him different.”

“From a producer’s and musical standpoint, Perry was the forerunner of dub music,” Mills agrees. “In the early days, he worked at different studios, and gained knowledge of the different rooms. In Jamaica, a lot of studios weren’t fully equipped, but he was the kind of guy that could make anything work. I learned from him how to go to a studio, and even if not everything’s working you make it work.”

For Mills, Perry’s music was evocative of a beautifully disorienting experience. “I compare dub with walking into a maze,” he states. “A place in your mind with colors and sounds. You walk into one room and there’s a bass, walk into another room and there’s a snare, each making different colors. His live shows were like a time warp, they kept building. You’re always saying, ‘What’s next?’ because you never knew what to expect.”

Similarly in the studio, Mills was constantly surprised by Perry’s ability to pull off potentially hazardous moves. “He used a simple Tascam board, but he was famous for using sound effects like the Mutron Bi-Phase,” he recalls. “I’d wonder, ‘How are you going to put the whole track through that thing?’ From an engineering aspect you usually only want to effect certain things. But he’d put the whole track through it, and it worked. And a lot of what I know about sampling, I learned from Scratch.”

Perry set up his famed Black Ark Studios in Kingston in 1973. The Tascam and Mutron were complemented by other classic gear like the Echoplex and Roland Space Echo, but literally any object imaginable could be pressed into sonic service. Perry’s clients at Black Ark included a long list of essential reggae artists including Bob Marley and The Wailers, Junior Byles, The Congos, Junior Murvin, Max Romeo, Mighty Diamonds, The Heptones, Augustus Pablo and Jah Lion.

“Scratch was into filtering from Day One,” Mills recalls of Perry’s techniques. “The Roland Space Echo was his main thing, and I remember going into his studio and seeing the Grampian (636) spring reverb. He was big on tube amps. Phase was a big part of his sound. He used to walk around with a Revox tape machine, because he liked the compression on it—he was very technical.”

But dub wasn’t just for audio engineers to geek out on. It was also a treat for the musicians who play it. “Dub is so far out and spacey—it’s very sparse, with a lot of space and effects,” says McDonald. “As a percussionist, that’s the best of all worlds. You had the space to play, and you can play some weird shit without people looking at you strange. In fact, they’ll probably look at you strange if you don’t play some weird shit! Scratch gave me a license to play exactly what I felt.”

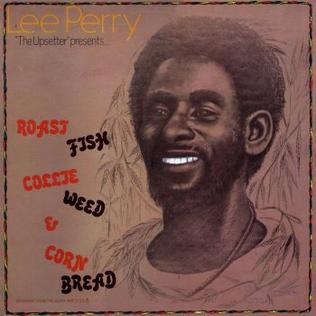

McDonald’s suggested listening for exploring Perry is the producer’s 1978 album Roast Fish Collie Weed & Corn Bread. “This was the record that showed you dub, and what dub was to become,” he explains. “It was a marked shift of dub reaching a different place.”

An Intergalactic Legacy

Lee “Scratch” Perry’s incredible output, and the equally incredible way he went about everything, add up to a truly irreplaceable artistic ambassador.

“Because of his physical appearance and his personality, he took his music out of Jamaica and made it worldwide,” says Sidney Mills. “That combination grabbed a lot of souls, because it was real. It wasn’t a marketing ploy, it was just him being him. He was a foundation for representing reggae music from a real roots perspective.”

“Every bit of acclaim that he got, he deserved,” Larry McDonald affirms. “He was a game changer in reggae. So many things started with him. He always loved to say, ‘Everything starts from Scratch!’”

— David Weiss is an Editor for SonicScoop.com, and has been covering pro audio developments for over 20 years. He is also the co-author of the music industry’s leading textbook on synch licensing, “Music Supervision, 2nd Edition: The Complete Guide to Selecting Music for Movies, TV, Games & New Media.” Email: david@sonicscoop.com

Please note: When you buy products through links on this page, we may earn an affiliate commission.

[…] Conga player Larry McDonald does an extensive interview about Scratch here. […]

[…] Originally Published on SonicScoop […]