How to Use the One Often-Ignored Button that Will Make You a Better Audio Engineer

What is this game-changing button I speak of? What single switch could take your lifeless recording and elevate your sound to stud status?

Your console or DAW’s polarity switch should be much more than an afterthought. Here’s how to make it an integral and powerful part of your workflow.

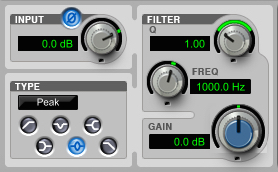

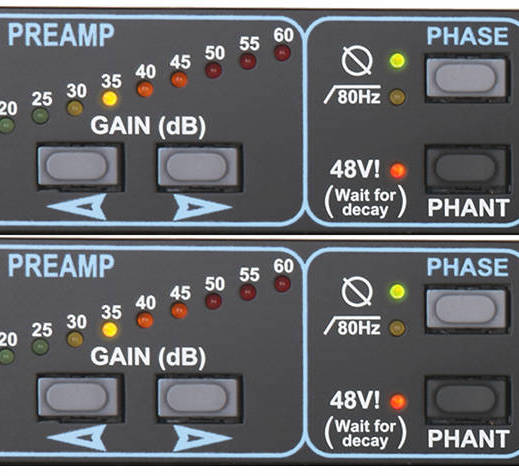

The single magic button, often confusingly and incorrectly labeled with the Ø (Phase) symbol, is actually not a phase switch at all, but a polarity inversion switch.

But to get the most out of it, you’re going to need an effective strategy for how, when and why to employ it.

Simply put, this switch inverts the voltage relationships of a signal, from – to + or + to -. The result will often be either a more or less cohesive phase relationship between multi-mic’ed signals.

Inverting polarity is especially useful when dealing with multi-mic’d sources, and can allow you to make sure the compressions and rarefactions of multiple complex sound waves work together, peaking and trough-ing in a more unified manner, thereby minimizing the cancelation of fundamental frequencies.

A quick technical note here before we get started: Addressing the differences between phase and polarity can be a polarizing topic in its own right (pun intended), and deserves to be addressed in detail in its own article that we’ll save that for another time.

To boil it down for the purposes of applying this powerful and overlooked button in your work, phase deals with relationships over time while polarity deals with simply flipping voltages from positive to negative, or vice versa. A polarity switch can help you deal with phase problems that arise, but strictly speaking, they are not the same thing.

For now, let’s stay focused and look more closely at how this mystical little button can help you in your audio pursuits.

Applications

Multi-mic’d drum tracks are the most obvious application of the polarity switch. But it doesn’t end there.

If you’re cutting a solo vocal with a single microphone, the polarity switch isn’t going to help you too much.

Polarity inversion comes most in handy when you’re recording a single sound source with multiple microphones.

Any time you’re using multiple microphones to record a single source, you absolutely must address phase relationships.

One common scenario is drum tracking. As a drummer myself, my love for drums and drum sounds is the reason I got into audio production in the first place, and the polarity switch has proven to be a powerful tool here.

Though there is no wrong way to eat the proverbial Reese’s when it comes to audio engineering—if it sounds good, it is good, and it doesn’t matter how you got there—I’ve come to realize that there are some techniques that help me get where I’m going much quicker and with less effort. Careful and deliberate incorporation of polarity inversion into my workflow has been one such technique.

Drums are often seen as one of the most intimidating things to get right as an engineer, and rightfully so, as there are so many moving parts. Any time you introduce more microphones into the equation, you’re setting yourself up for the opportunity to experience phase anomalies. (There’s that word again, “phase”.)

While the issues that arise are indeed phase problems, caused by the fact that the same source signal reaches multiple microphones at different times, a simple and effective solution is often to invert polarity.

But with so many channels to choose from, how do you quickly and reliably figure out just where to flip the polarity to improve your tone?

Polarity Procedures

Chances are, your audio instructor or favorite magazine writer who told you to flip the polarity on your bottom snare track only told you part of the story. Perhaps you followed that advice blindly (or is it deafly?) and missed the bigger picture.

For the sake of this exercise, let’s say you’re recording a full drum kit and you have a pair of stereo overheads, a kick microphone or two, snare top and bottom microphones, individual tom microphones, various ambient microphones—and maybe even more than that.

The exact combination of signals here is irrelevant as long as every time you introduce new signals to the equation, you check the contextual effect of the polarity switch on the newly introduced signal.

Whether you’re working with multiple mics or layered samples, developing an effective approach to polarity choices is key.

First off, in general, the easiest way to perceive phase discrepancies will be by listening in mono.

I like to pull up overheads first, and use them to capture a complete and full-bodied image of the entire kit.

(There are many amazing engineers who prefer to use overheads primarily as cymbal mics and will roll off a lot of low-end information. Either way, the procedure is the same.)

Once you have your overheads up, your left-right stereo balance feels good, and the kick and snare are sitting in the overhead image where you feel appropriate, switch to mono and hit that polarity switch on one side of the overheads or the other.

If the bottom falls out and your entire drum sound turns into a wimpy pile of nothingness, then you know you’re on the right track! Disengage that button and proceed on with your polarity as normal. Your overheads are now dialed.

Next, go ahead and pull up your kick drum in conjunction with your overheads. Try to boost the level of your kick until it is comparable to the summed total of your two overheads. Matching the level will help you better hear the phase interactions when you switch the polarity.

Now, flip the polarity on your kick channel. Do you lose or gain impact and body? Obviously, leave it set to whatever position preserves the girth and impact of the drum sound.

Are you noticing a theme here? When phase is not right, one typical red flag will be a loss of low-end information. This is almost never the desired effect.

(That said, I’ve known very talented engineers who like to leave certain mics out of phase because they like the EQ curve it creates when combined with other signals. While there isn’t necessarily anything wrong with this approach, it’s never been one that I’ve wanted to adopt.)

Now that you have determined the appropriate polarity relationship between overheads and kick, feel free to introduce your snare top, followed in turn by your snare bottom, hi-hat, toms, and so on.

The important thing is to make sure that every time you introduce a new signal into the sum total of the drum sound, you flip that polarity switch in context and decide if it plays well with the rest of the microphone signals.

Here’s the catch: If you ever find yourself flipping polarity and you can’t really hear a difference, then I’d suggest you try moving that new microphone around.

When there is little discernible difference between the two options, then there’s a good chance that your current mic placement is close to 50% out of phase. In my experience, that kind of placement isn’t setting you up for success. Halfway between great and terrible is not the kind of happy medium you want to find yourself in.

If you already “know” that all this is something you should be doing, then great! Let this serve as a reminder not to flag in your practice.

I know a multi-GRAMMY-winning engineer who once summed two snare signals to a single track, only later realizing that the two signals were severely out of phase. As his trusty assistant put it, “it bit him in the ass”.

Don’t worry, the crisis was eventually averted and that track still made it onto the radio. But this goes to show you that it can happen to anyone. Never forget just how powerful a good phase relationship can be—and just how much a bad one can derail your tone.

Dueling Disclaimers

It’s often a good idea to double-check the impact of the polarity switch before and after EQing a signal as well. Like it or not, your equalization moves can impact these phase relationships, and the EQ moves you make in isolation can end up sounding different than you anticipated when you hear them in context.

This is one reason I often prefer making EQ moves to a drum bus (or any other multi-mic’ed bus for that matter), rather than tweaking the EQ on each individual channel. It’s also a good reason to try and always EQ in context.

Sometimes, we get so focused when making EQ moves on a single source that we don’t realize we’re digging ourselves a hole somewhere else. This is especially so when EQing outside of the context of the whole instrument or the entire mix.

As a final note here, when you’re flipping polarity on distant or ambient microphone signals, it is sometimes more difficult to distinguish which position is favorable. Feel free to move mics around if need be, but ultimately go with your gut.

The extra-complex, washy phase relationships are part of what give ambient sources a sense of space and dimension, so getting the phase as coherent as possible is both more difficult, and less essential to the impact of your sound than for your closer mics.

Polarity Switching is Not Just for Live Tracking or Multi-Mic’d Instruments

Obviously, similar considerations apply when you are using multiple mics on guitar amps, on full ensembles, or when combing mics with DIs on a single source. But these principles don’t only apply to live instruments.

As sample supplementation of live recordings becomes more common to achieve a modern hybrid drum sound, attention to phase relationships remain a very important when blending live signals together with samples.

Be sure to always listen to the impact of the polarity switch, even when you’re adding samples to a live kit. The same even holds true if you are working exclusively with drum machines and layering drum samples on top of each other to create new textures.

Similar considerations can also be beneficial between instruments: For instance, when combining instruments such as kick drums and bass guitars that often play on the same beat together.

I’ll admit that the polarity switch is most valuable in situations where multiple microphones are in close proximity to one another and share a somewhat similar distance to the sound source. But don’t neglect it elsewhere.

Summing it Up

While polarity inversion isn’t exactly “fixing” the problem at hand, it often does provide an immediate solution that will help you acquire a much more pleasing sonic result, and fast.

When I’m tracking, it is my goal to make tunes sound like finished records from the onset. And when dealing with multiple microphones on a source, this little button helps me get closer, faster, every-single-time.

The best time to get this right is at the tracking stage. But when you reach the mix stage, audition the polarity switch just as you would in a tracking scenario. If, after doing so, you find that your drums are already sitting right, then your tracking engineer was a baller. Call them and thank them for making your life easier.

While multiple microphones on a singular source will never be “absolutely and totally in phase”, you can usually find a sonically-superior happy medium that delivers complexity, control, and great tone all at the same time. So get out there, throw up some faders, and test different combinations with your new secret weapon.

Bottom line: You can’t fight physics, so stop trying. Flip the problem on its head with the polarity switch.

Jasper LeMaster is a an audio engineer who lives and works in in Nashville, TN. He has extensive experience in both music and sound for film.

For more great insights into mixing, try our full-length course with SonicScoop editor Justin Colletti, Mixing Breakthroughs.

Please note: When you buy products through links on this page, we may earn an affiliate commission.