Behind this Soft Synth is a Saga: The Emotional Road to SAW-1 Discovery

How do new soft synths arrive into the world? Are they brewed up by Magical Elves who just love insane new sounds? Perhaps there are creative creatures who live deep in the woods, rubbing their hands together in a mischievous cackle as they cast a spell, transforming pure ether into a wondrous sonic source for EDM heads around the world to get off on.

No one would blame music producers for thinking that’s what happens. After all, installing a fresh new software synthesizer into your system is just about the easiest way to mainline rushes of inspiration. When it’s done right, arriving when you need it, a soft synth doesn’t just deliver a landslide of new instrumentation ideas – it provides the opportunity to invent a never-heard-before sound on the spot. Load a patch, mess with the presets, and within a few glorious seconds you can be The First Person on the Planet to hear what magic materializes.

Hate to burst your bubble, but in the vast majority of cases soft synths are actually not made by Magical Elves. As you’re about to find out, the synthesis instruments that populate platforms like Reason, VST-hosting DAWs, or standalone stem from somewhere else entirely: They initiate in a place of incredible passion for sound, an awe for artistic achievement, and a drive for technical excellence. On the way its creators must prepare for tedium and despair. Unparalleled triumph is the potential reward for the work.

Such an adventure was certainly the case for J. Chris Griffin in his quest to create SAW-1 Discovery. An extremely powerful sample-based synthesizer based on vintage analog sawtooth wave recording, SAW-1 is stocked by waveforms recorded with ultra-high sample rates, vintage equipment and an obsessive attention.

A prolific record producer and sound designer (Madonna, Kelly Clarkson, John McLaughlin, MTV), Griffin constructed SAW-1 from fourteen unique layers consisting of over 940 analog samples, then converged with a relatively modest ambition: Generate some of the biggest sounds ever created using just one device.

Benefitting from the latest advancements in widely available computational speed and memory, there are over 130 samples per Oscillator choice in the dual-layer SAW-1. Sampled by Griffin, a studio perfectionist who painstakingly created beloved Reason refills like Electromechanical, each key sounds precisely like it does on the original instrument, when Single Saw or Dual Saw is chosen as the Oscillator source. Virtually no artifacts, fidelity issues or interpolation problems are present as players move up and down the keyboard.

He Saw the Saw

Griffin’s drive to make SAW-1 wasn’t so much about realizing a sound in his head but paying proper tribute to the waveform that resembles a plain-toothed saw with zero rake angle. That’s right: the sawtooth wave.

“I’ve always been enthralled with sawtooth waveforms on a synthesizer,” Griffin says from his studio in Manhattan’s historic Financial District. “From first experiences with a borrowed MiniMoog to the first time playing a 16-voice Waldorf Q+ with the analog filter set at a NAMM show — which was so utterly amazing to me at the time — the quest has been to recreate what my mind recalls from those special moments.

“Unfortunately, my mind recalls a much thicker, and better, sound than what was actually presented, so the search has been nearly impossible,” he continues. “It’s funny how the mind fills in and thickens sounds isn’t it? I find this with music too – especially from the ‘80’s. I remember those songs and productions being so lush and thick, but listening back they are anything but thick. It’s so weird, but it creates this quest to find or develop sounds that embody the imagined thing.”

In 2016 Propellerheads, the Stockholm-based makers of the hugely powerful and influential music production system Reason, asked Griffin to update a series of patches he had originally created for their Rigs 1 and 2 Bundles. “Normally there are strict guidelines to follow with factory patches,” notes Griffin, “but I have been working with Propellerheads since 2004, starting with the Electromechanical Refill, and they finally set me free to create ‘ultimate’ patches regardless of CPU hit. I realized that modern computers were nearly able to create those sawtooth textures that were in my mind.

“It takes a lot of work to generate compelling and engaging sounds for a hit song. Producers layer and tweak several different synthesizer instruments to be part of a greater whole, especially with sawtooth sounds.

“Until now, no single synthesizer could dare make a sound big enough to capture imagination and attention like a stacked layer, but I had a stash of ARP 2600 saw waves that just might accomplish this goal. The result was exactly what was in my head and more –2000 non-repeating, individual oscillators all going at the same time.”

Above all, Griffin was determined to bring an entirely new sawtooth experience and possibilities to music artists, electronic music producers, and content creators of all stripes –enhanced unabashedly by his own artistic perspective.

“There are a few general concepts that drive me,” Griffin says. “First is what I call ‘Thick, Rich and Chocolaty.’ There used to be these frosting commercials that used this phrase and it defines what I look for in a sonic landscape, whether it be in one of my productions or a synth patch. I want to go inside of a mix, look around and have each instrument close enough to ‘touch’ with merely an arm stretch. That’s thick to me.”

Next, Griffin set his sights on matters of size and largesse. “The instruments may be close but my imagined space is immense,” he states. “We are creating the illusion of space with sound – much like filmmakers do with cinematography. How can we help a viewer or listener perceive three dimensions when in fact there are only two? In photography and film, shadows and light create the illusion that a tree is in front of a person, but that’s impossible in a 2D space. It’s just an immersive illusion – we never think about it or question the reality of it.

“The same is true in music. Let’s make a drum kit sit in front of a guitar or create a space that sits behind the lead vocal and gives it depth when, in reality, there is no depth at all: It’s two transducers on a firm X-axis. There’s not even a Y-axis! How to create the illusion of size and depth with only one dimension axis? How do we create a large enough space to suspend reality but keep focus on the immediate story?”

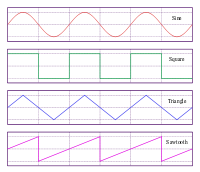

That’s where Griffin’s fave wave walks in. “Saw waves for me embody the best harmonics (odd) for dimensional manipulation. It’s the one waveform that includes both the fundamental frequency and harmonics that command attention without having to distort the sound.

“A sawtooth wave is kind-of annoying on its own, right? That’s why they are so popular for bass sounds, pluck sounds and lead sounds. They cut through a mix and cut through our imagination, forcing listeners to pay attention.

“Without focused attention on the right part of the story, a song cannot be a hit. In my view, sawtooth waves do this better than sine waves or square waves – and they can be effective without distortion, allowing a skilled producer to alter depth and attention to perfectly fit a musical story.”

The Reason for Reason

A clear synth vision was organized in his head. Now, Griffin had to identify the ideal platform, which for him was an easy decision.

“I love Reason. Reason is used on every production done here at my studio,” he states. “It’s permanently Rewired into Pro Tools for its synthesizer selection. No product includes so many different sound generators – at any price. I’ve been a fan and evangelist for Reason since 1.00 and have been deeply involved with Factory patch creation since Version 3. In effect, I’ve put my private soundbank inside the Factory set, so I’m uniquely invested in Reason.

“SAW-1 Discovery was made for me. I made it for my productions because I was so tired of layering synths together to get those magic sounds that I just made a device that could do it all. There’s more to the story of course, but that’s the genesis of SAW-1. However, as soon as I realized this synth might have value for others the question became, ‘Should I make it as a Rack Extension or try to get an AAX/AU/VST version made?’”

The answer to that question lay in a dinner conversation Griffin had several years ago with a friend who that also a prominent plugin developer. “We were discussing copy protection and related concepts when he mentioned that once a plugin becomes a VST the money just stops – it gets cracked and that’s it,” recalls Griffin. “A few legitimate users still buy it of course, but instead of proper ROI on a wildly popular plugin, it becomes crack-management and legal wrangling with anonymous criminals that think they’re actually helping the manufacturer by making the plugin more popular.

“The Rack Extension format is a perfect foil for this because it’s a closed system, much like the Apple Store or Google Play. SAW-1 will have less exposure and popularity, but I’ll get a proper return on my investment over a reasonable time.”

Crossover to Code

Griffin was chomping at the bit to dig in and start coding up SAW-1 personally, but there was just one small thing: He had no idea how to code.

“I’ve wanted to develop synths for a long time but third-party coders and graphic designers were expensive and needed significant time to learn how synthesizers implement information,” he reasons. “I didn’t have enough savings to invest serious money into something that might not even work, so my ideas sat dormant.

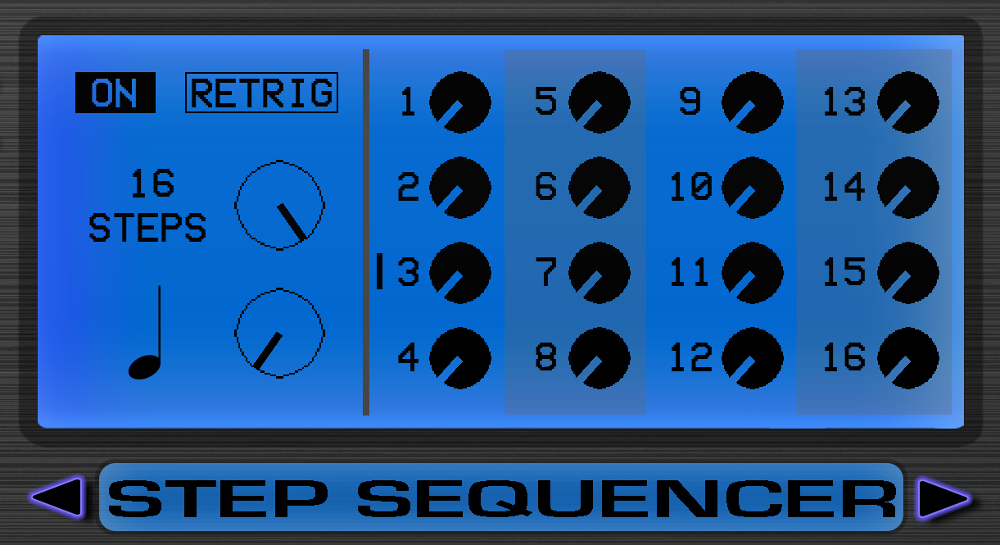

Baby steps: Griffin had to fully develop his coding skills before he could assemble SAW-1 components like the step sequencer.

“In April of 2016 our family experienced a significant tragedy. I didn’t feel like working with clients for many months after that, and to keep myself from getting totally lost I needed a new hobby. Coding and scripting seemed good so I printed a ton of manuals and set about learning Python, Lua and various scripting languages. I signed up as a Propellerhead Developer and downloaded their software development kit. Since I am friends with most of the guys at the company anyway I asked questions, bugged people and begged for any education they were willing to give.”

Calling coding a “dark art,” Griffin notes that certain essential kinds of written documentation can be hard to come by, and not just when it comes to Reason. “It’s a lot of trial and error/back-and-forth with those who have gone before. I had to prove myself to some of the guys before they would give me their ‘secrets,’” he says. “Each night after work I chose a specific problem to solve and would stay up until it was worked out. There were so many things to deal with it took over a year, but it was like a gigantic puzzle and I enjoyed the challenge.

“Furthermore, it reminded me of the capacity for learning; we aren’t glued to a specific knowledge set or field of influence unless we choose to be. It was gratifying to know that monstrous leaps were still a possibility even though I’m older and somewhat locked into a particular skillset.

“Each milestone and each new problem solved made me feel like The Incredible Hulk breaking out of his day clothes to become something fantastic and awesome. Not that I’m fantastic and awesome! But I do feel like The Hulk.”

Very Serious Sample Sources

Ironically, a cold-blooded business decision was at the heart of the iconic ARP 2600 becoming the central sound source to SAW-1. “I have a rough policy that whatever doesn’t get used on an actual record in one year’s time gets considered for sale,” explains Griffin. “Then I buy something new that will actually help make a record.

“Unfortunately, in 2011 my beloved ARP 2600 found itself in this category. My then-new Virus TI Snow just ate it for lunch. So bummed, but I sold it anyway. Before it sold however, it occurred to me that I could ‘stack’ ARP 2600 recordings the same way we stack background vocals or power-chord electric guitars. The ARP has free-running oscillators, so the chance of any note sounding the same as a preceding note is near zero. Nothing compares to non-synced analog oscillators running in tandem for largesse and thickness.

“So, I set about recording the ARP 2600 – specifically sawtooth waves. The system was set on a loop overnight for several weeks, recording every single key from Midi note 0 to note 127. That’s a ton of data but the result sounds absolutely fantastic.

“SAW-1 Discovery waveforms 1-5 are exclusively ARP 2600 sawtooth waves and stacks. Waveforms 6 and 7 add several Reason synths (with patches I created for their Synth Rig 3 bundle) and the Virus TI to the ARP stacks. It gets fairly insane but it’s a gorgeous insanity.”

When it comes to sampling live instruments for recreation with a sampled synth, Griffin knows the insane attention to detail needed for such a task, dating back to 2004 when he crafted the “Electromechanical” Reason vintage keyboards refill. Griffin can testify first hand to the turbocharge sampled synths have gotten since then, with vastly faster computing allowing better results for both the sampling audio engineer and the artist/producer/composer end user.

“Back then RAM was a huge limiting factor,” says of the “Electromechanical” sessions, which saw recordings take place at iconic studios such as Avatar. “The computer used for those sessions didn’t even have 1 gigabyte of RAM, it had 768 megabytes! so sampling every key or multisampling beyond four layers was out of the question.

“Modern RAM capacities and OS implementations have eliminated this bottleneck so I could just load up without restriction. I’m still looping but the loops now last a minute or more. Every white key is host to a new sample so interpolation is kept to a minimum – no more than one note in any direction. The resulting sound is incredibly organic and indistinguishable from the original sound across the keyboard – even though it’s sampled. I never imagined it would turn out so well.”

But accurate capturing and faithful recreations were only the beginning. From there, a huge playground opened up to Griffin as he began to assemble an array of custom patches. There was now an incredible range of options available with SAW-1’s seven different oscillator choices. These include Single Saw (one single-oscillator sawtooth waveform per layer), Dual Saw (two single-oscillator sawtooth waveforms per layer), Multi-Saw 1 (twelve vintage ARP 2600 sawtooth waveforms per layer (slightly detuned from one another), Multi-Saw 1 (sixteen vintage ARP 2600 sawtooth waveforms layer (moderately detuned from one another), SuperSaw (a “tame” multisynth layer combining the ARP stack with other sawtooth-wave synths), What The… – Club Ready, containing hundreds of sawtooth waves from multiple synths, and The Trinity – “the embodiment of sawtooth-wave sound” where over 1000 unique sawtooth waveforms per layer combine.

“With a commercial product there has to be a balance of textures,” Griffin says. “Small, large, thick, thin, moving, static and phrase-based patches have to be part of the factory soundset. Within each category a balance of textures should be included.

“However, they can’t be bad patches! I specialize in the aforementioned ‘thick, rich and chocolaty’ patches — especially pads and textures, but also utilize super-thin lead sounds and analog bass sounds that use one or two oscillators. I’ve got those covered with natural intuitiveness. I’m not intuitive in all areas — no one is — so I draw inspiration from other synthesizers that people love.

“Think of the top three synthesizer plugins in music today. I’ve listened through their factory sets and drawn inspiration for patches that might not come naturally to me. For example, thin pads aren’t something I know about naturally, but when the synth-of-the-moment has a whole folder of thin pads I’m investigating that sound and learning how these patches are used in a song. Then I listen to music and try to identify how these sounds function in recent hits. After that, patches are created and tweaked. I’ve learned more about the latest production trends in the process.

“Synth development has been very good for my music education! It helps me stay on top of trends and stay ahead of the curve when composing beats or songs.

Down to the Nitty Gritty: From the GUI to Beta Testing

There were no shortage of surprises along the way, as Griffin descended down into a deep rabbit hole where audio, backend coding, SDK (Software Development Kit) issues, GUI design, and beta feedback vied for his energy and attention.

“The gaps – oh my!” laughs Griffin about the SDK. “It turns out that EVERY manufacturer has gaps in their SDK because of the ethic between fellow programmers – no self-respecting programmer gives away ALL of the secrets! This realization was jarring and wasted a lot of my time, but it is the way it is. I’m not the person to challenge this ethic or change an existing culture. It is for me to fit in or get out.”

The SAW-1 GUI. Crafting the synth’s visual aspect was a fresh challenge for the musically-focused Griffin.

Griffin soon realized that the GUI implementation was actually more challenging than creating the synth engine. “Tying each pixel to the original Photoshop design, exporting elements and animating them accordingly took more time and effort than figuring out how to make the filter sound great,” he says. “What does a shadow do on a knob top as it’s turned in real life? Should I play with the lighting across know travel to emulate? Is text clear enough or large enough? Is shadowing and texture consistent and believable throughout the GUI? How many frames of animation for knob travel? What size should it be? Is this knob more important than another? Fader or knob? Black or blue?

“Everything has to be decided and programmed accordingly. Given the fact that I’m a music pro and not a graphic designer these questions sometimes become paralyzing.”

Finally, SAW-1 was ready to roll out for beta testing and QC at the hands of others. But as mountain climbers discover when they reach the summit, the work is only half over – now you have to come back down in one piece.

“Propellerhead put out a request for beta testers and 20 people signed up, including some fellow developers,” says Griffin. “Version Beta 1 was the best I could come up with by myself but the beta guys came up with so many ideas, suggestions and change requests that I was busy for six more months.

“In the beginning many testers would write paragraphs and paragraphs giving their opinions and probing my thought processes. It was hard to hear in many cases but it was pure gold. It’s much better to hear complaints in beta with people who want you to succeed than to wait and hear complaints when it affects the bottom line.”

Griffin outlines the beta process thusly. “Put out a beta, request comments, get eviscerated, make the changes and start all over. SAW-1 Discovery went through 21 or 22 beta stages before it was released. Admittedly that’s more than I wanted but it was my first release and it needed to be right. Since release, no bugs have been found. Even though it was hard to hear the critiques, it was such a valuable season!”

Although the beta group could be tough, Griffin took it as tough love. “Comments on color, function, placement and features were so valuable and put forth with such grace and care that I couldn’t help but implement the changes,” he says. “For example, some people hate the GUI, some people love it. Adding different skins solved much of the problem. Another example was implementation of dropdown menus versus click and drag, especially with the Quality and Polyphony parameters. There was a glitch in the GUI which made click and drag inefficient and the beta team convinced me that regardless of reason, it had to be changed.

“Lastly, the team pointed out inconsistencies in fonts, text size, spacing and nomenclature that I would have never payed attention to. To me, sound quality is the most important, but it became very clear that once sound quality reaches a certain threshold looks and consistency become paramount.

“I suppose there’s more commentary to be given on that subject, but who am I to argue with what is? I want things to be a certain way and potential buyers want it to be another. If sales success is a goal the product will satisfy both groups. That was a valuable — and painful — lesson to absorb.”

Unexpected Discovery

Released in summer 2018, SAW-1 Discovery has been available long enough to give J. Chris Griffin equally needed feedback from the field, and respond in step to a deeply appreciative user base.

“Feedback is great! Everyone who writes is thrilled with the sound and quality of patches,” he says. “It’s a niche synth so it will only appeal to a specific group, but that group is responding better than I hoped. Of course there are haters on the forums who assume their opinions are news to me, but there are only a few of those. They truly don’t inform decisions or force changes. The users with specific comments given via proper channels — emails or phone calls — get the most attention.”

In that way SAW-1 Discovery will continue to evolve, as Griffin allows himself to become more streamlined and purposeful in his development role. “There’s a meter on one of my new synths that doesn’t really need to be there – it’s just fun and a bit humorous – but I can’t make it look quite right,” he notes. “In the end I just eliminated it in favor of a unified color scheme and streamlined function.

“That’s the goal anyway right? Do a job well, be clear, avoid distractions and blow users away with the main thing — sound quality and functionality.”

- David Weiss

Please note: When you buy products through links on this page, we may earn an affiliate commission.