Charlie Watts in the Studio: Audio Insights on a Different Drummer

The Rolling Stones certainly have contributed their fair share to the audio industry. They’ve recorded 30 studio albums, 33 live albums, played 2,000+ live shows, plus scores of TV appearances, documentaries, and movies. This one band has provided nonstop work for countless audio engineers, producers, mixers, and audio post since the early ’60’s.

Arguably, only a tiny fraction of all that recording would have happened if the Stones had a different drummer. Their drummer was always Charlie Watts, who passed away on August 24th at age 80.

He joined the band in 1963, and we can only imagine what a life he lived in the six ensuing decades. What was it like to have his unique perspective on a Rolling Stones concert? Picture the world’s greatest entertainers by your side, electrifying one million people as you play upon your throne. It would be as if Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, Brian Jones, Bill Wyman, Mick Taylor, Ron Wood, and many more were doing it just for you.

Charlie Watts: The View from the Studio

Jimmy Douglass’ career as an engineer, mixer, and producer launched in his teens. Today, his acclaimed discography includes Aretha Franklin, Led Zeppelin, AC/DC, Missy Elliot, Jay-Z and Kanye West, Timbaland, and many more.

As his discography took off, Douglass was asked to assemble and mix the Rolling Stones’ 1977 live double album Love You Live. He also engineered and mixed multiple tracks for them, including the Stones classic “Fool to Cry” on Black and Blue.

From his own front-row seat in the studio, Douglass experienced Watts up close. “He was always the grownup in the room,” recalls Douglass. “He was simply no nonsense. He would go in and play his part, deadpan even. He didn’t say much about it while the band was doing their antics.”

Playing to stadiums was a similar story. “He was the same dude,” Douglass says. “He would just be there, doing what he does while everyone else acts crazy. He underplayed everything, but man was he there. I always wondered how he was so chill in the middle of all that chaos.”

Bob Clearmountain is well known for his contribution to the music landscape as an engineer, mixer, and producer. His deep discography contains David Bowie, Chic, Roxy Music, Bruce Springsteen, Bryan Adams, INXS, and hundreds of other artists.

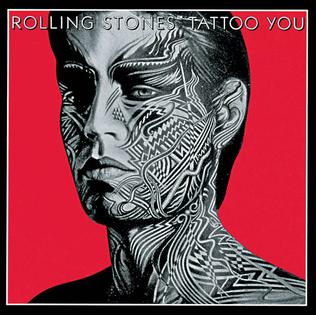

Generations of rock fans were raised on the sounds Clearmountain mixed for the Rolling Stones’ 18th studio album Tattoo You. It’s a big record that includes “Start Me Up,” “Hang Fire,” and “Waiting on a Friend.” He also mixed their 1995 live/acoustic release Stripped, the Martin Scorcese-directed Shine a Light 2008 concert film shot at NYC’s Beacon Theater, dozens of concert videos, and more.

Here’s how Clearmountain explains Watts’ drumming style. “Like you were in a fast car, and you’re driving right at the edge of a cliff. You’re so close, you’re just brushing the railing there. The edge. That’s the kind of drummer Charlie was. It always feels like it’s going to come apart, but it never does. It just keeps going.”

Watts’ incredible longevity, playing with the Rolling Stones for 58 years over all those albums and concerts, cemented his legacy. His playing inspired decades of drummers, who craved something which Watts alone could deliver. “Charlie played a big part in influencing all sorts of drummers,” says Clearmountain, “including jazz and pop as well as rock drummers. He had an extremely unique style, and it wasn’t about keeping perfect time.”

Watts inspired another surprising genre, according to Jimmy Douglass. “I think his drumming had a lot to do with the punk age,” he observes. “I grew up in a studio musician era, with the Bernard Purdies, and they were right on it. The Stones stuff was loose, it gave you the right to not be perfect on everything.

“Punk music was was ratty as shit, and the rattier the better. I’m not putting it down, that was the signature: ‘Look how far out there we can be and still offer something that fills your soul.’ He was the beginning of that whole thing.”

“Never ask a drummer to play like Charlie Watts!” warns Juan Cristóbal (JC) Losada, the Miami-based GRAMMY and Latin GRAMMY winning producer, mixer, engineer, songwriter, and drummer. “It’s harder than you think. His talent, his feel, can’t be replicated. You can use him as a reference point, but not to be copied.

“Charlie Watts’ drumming was about consistency, less is more, impeccable timing. Also a very good use of the pocket: sometimes playing the back of the pocket, that last millisecond. He could play those slow feels at the back of the pocket, but at the same time he could play the faster, four-on-the-floor.

“He played a French grip technique, which is thought of as a softer touch, but he would slam it, especially the rim shot while also striking the snare. His transitions became a part of the Stones’ hooks, and a centerpiece of the songwriting. Hats off to the many audio engineers and producers who captured his impeccable sound live and in the studio.”

Mixing Rolling Stones Rhythm

Clearmountain developed his own Rolling Stones viewpoint while mixing Tatto You at NYC’s fabled Power Station. “From a mixer’s point of view, Charlie Watts had a feel that no other drummer on the planet could possibly duplicate,” he says. “His snare drum was always perfect sounding. And he hardly ever hits the high hat at the same time as the snare, which is a mixer’s dream.”

Bob Clearmountain mixed 1981’s “Tattoo You.” (Image credit: The cover art can be obtained from Rolling Stones Records/Virgin Records., Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=20133041)

Clearmountain continues, “He wasn’t a basher like a lot of rock drummers. He was almost a jazz player—he hit the snare lightly, but in a way so it would just resonate. His snare always sounded so good you never had to do anything in particular – just add a little treble and it was perfect.”

Watts’ jazz tendencies often called for kick drum solutions, however. “His foot was very dynamic,” says Clearmountain. “It sounded great, but he could be light and then he’d push it hard. It’s perfect live, but it’s different for a record. I would sometimes sample his bass drum and trigger it. So it’s still his bass drum, but now I could reduce the dynamic a little bit.

“Either that or I would compress it in a way that would even that out, for a little more consistency on the record. I probably sidechained it. Using a sidechain with an advance trigger, you can keep the sound intact and still control the dynamics.”

Losada’s credits include Carlos Santana, Ricky Martin, Enrique Iglesias, Plácido Domingo, José Feliciano, Shakira, José José and Chayanne. He is also EVP Global A&R for NFT music player GLOZAL. His 2017 Latin GRAMMY win was for mixing Jon Secada’s masterful To Beny Moré with Love, a complex project recorded by Secada and a big band in Puerto Rico.

“When you look at the live recordings, the miking techniques on Charlie Watts were a lot of ambient mics—not close miking,” Losada observes. “Just capturing the overall ambience of his set. That trashy ride cymbal, the toms.”

Douglass divulged deeper wisdom from mixing Rolling Stones rhythms. “I did learn a different pocket of the groove,” he says. “As opposed to what I was used to from R&B, funk, American rock and roll. They changed my whole style of recording and mixing—the bass wasn’t where you were used to, it was over here. It wasn’t the classic R&B and funk. It was almost light the way they were doing it, but it was right on.”

Influencing Producers

When working with artists in the studio, Losada channels Charlie to create space. “Sometimes less is more,” he explains. “I use my drummer’s background to produce drums. The inspiration Charlie brings is, ‘How can you be consistent on that grid but also be flexible, let the drums breathe in and out?’

“In the subdivisions you feel the swing, but what happens in between the quarter notes…That’s where you’re like, ‘Oh my God!’ Listen to his work at the beginning of ‘Start Me Up.’ It’s simple yet innovative. Simple in the good sense. There’s no acrobatics, its boom-boom-bop.”

In turn, Losada loves to apply the Charlie mindset to all music production aspects—from tracking to producing to mixing. “Again, less is more—focus on capturing the performance and ambiance, focus on consistency,” he says. “If I need to bring the ‘Charlie Watts’ out of a drummer, I may ask them to imagine zooming into the click in slow motion, and then you can play inside of the click. You can play in that moment. You don’t always have to play on top of it, you can play ahead or behind it.”

Travels with Charlie

Watt’s all-business gameface belied his true nature, a ready wit lurking just beneath the surface. “I remember setting up Charlie’s drums for the Shine a Light movie at the Beacon Theater,” Bob Clearmountain remembers. “He rarely tuned his drums. He didn’t have to because he didn’t hit them hard enough to wear them out.

“I wanted to tune his floor toms a little bit. I asked the drum roadie, ‘Do you think he’d mind if I touched it up a little bit?’ and he said, ‘It’s probably all right.’ When Charlie came onstage, he came up to me and said, ‘I heard you messed with my drum tuning!’ Then he started laughing. He was very sarcastic. I loved that about him.”

And Clearmountain noticed yet another thing to envy about Charlie Watts. “He got better as he got older,” says Clearmountain. “There was a period when I was sent archived shows spanning the last 50 years. I mixed shows from 1971, at the Marquee in London early on, right up through a few years ago.

“I got a sense of how the band evolved, and Charlie just kept getting better. He’s a skinny guy in his 70’s, and he’s playing his ass off! During a two-and-a-half hour show, he never let up.”

So who had the best seat in the house? Perhaps it was the legions of Rolling Stones fans, rocked to the core by our world champion drummer. But it just might have been Charlie Watts, making magic from a Gretsch four-piece. “He had a pocket that was his,” says Jimmy Douglass. “What was it? I can’t really tell you. But it was his.”

— David Weiss is an Editor for SonicScoop.com, and has been covering pro audio developments for over 20 years. He is also the co-author of the music industry’s leading textbook on synch licensing, “Music Supervision, 2nd Edition: The Complete Guide to Selecting Music for Movies, TV, Games & New Media.” Email: david@sonicscoop.com

Please note: When you buy products through links on this page, we may earn an affiliate commission.

[…] The Rolling Stones certainly have contributed their fair share to the audio industry. They’ve recorded 30 studio albums, 33 live albums, played 2,000+ live shows, plus scores of TV appearances, documentaries, and movies. This one band has provided nonstop work for countless audio engineers, producers, mixers, and audio post since Read more… […]

[…] The Rolling Stones certainly have contributed their fair share to the audio industry. They’ve recorded 30 studio albums, 33 live albums, played 2,000+ live shows, plus scores of TV appearances, documentaries, and movies. This one band has provided nonstop work for countless audio engineers, producers, mixers, and audio post since Read more… […]