Making Money with Library Music: The Details of the Deals

Follow the money! This week we learn the ins and outs of collecting fees and royalties for your music.

In my last post about making money through music libraries, I wrote about the different types of library models, the kinds of deals they offer, and how best to submit your material. If you’re new to the world of library music, it’s a great place to start.

Today, we’ll go deeper into the money side of the business to talk about how the system works and what you need to do to get paid.

The Payments

When you start getting your compositions placed with music libraries, there are two kinds of payments you might expect to collect: “fees” and “royalties”.

A fee is a one-time payment made to you to secure a license to use your music. A fee can also be an amount paid to you by a library to purchase the exclusive rights to represent your music, or to buy you out completely, as in a “Work for Hire”.

A royalty is generally paid in a broadcast situation. Each time your music airs, you are entitled a royalty.

The Sync and Master Fees

Let’s start by taking a closer look at fees.

First up is the “Sync License Fee”. A music synchronization license, or “sync” for short, allows the licensee to synchronize the composition with some kind of visual media output such as film, video, or TV.

Note that we’re only talking about the composition here. The licensee is paying this fee for the rights to use the underlying musical composition—not any specific recording of the composition. That is handled with a second fee called a “Master License”.

A Master License grants the licensee rights to use a particular recording of a composition. The Master License fee is obtained from the person who owns the recording (aka the “master”). This isn’t necessarily the copyright holder—though in the library business it usually is.

With music libraries, the sync and master licenses are usually combined into a single fee, and being able to provide both of these types of licenses at once is known as “clearing both sides”. This kind of fee can be collected by either an exclusive or non-exclusive library, and the split depends on your contract with them, though the industry standard is 50/50.

To “follow the money” with a common real world example, imagine this scenario: You create a piece of original music and submit your recording of it to a music library. The library makes it available from their catalog, and a client purchases the licenses to use it in his or her project. Both the Sync and Master Fee is collected by the library and split with you.

There is no statutory rate for the amount of a Sync and Master fee, which means that the exact amount your music will sell for is negotiated by each library.

The Upfront Fee

Another type of fee you may come across is the “up-front” fee. As part of your deal with a library, they may pay an up-front fee per song to purchase the exclusive rights to represent your music. (These rights may or may not revert back to you after a period of time, depending on the deal you negotiate.)

If you are paid an up-front fee, it sometimes means the library will keep 100% of any future sync or master license income under the duration of the contract. However, the writer will usually retain the writer’s share of the public performance royalty income. More on that below.

The Work for Hire Fee

You may strike a deal with a library to provide music for them under a “Work for Hire” or “WFH” agreement. In this case, the fee is purchasing more than just the rights to represent the music—it is purchasing the actual copyright to the composition.

In this scenario, you no longer own the music. The company paying you is now considered its author and copyright owner in law. Legally, the company can now be credited as and collect any royalties owed the writer. Whether they do so will depend on the deal you make, as WFH contracts can still allow for the original creator to collect performance royalties.

Performance Royalties

A performance royalty is owed to the writer and publisher of a song whenever that composition is broadcast or performed in public. These fees are collected and distributed by a Performance Rights Organization, or PRO.

The PRO pays 50% directly to the publisher of the track (usually the music library) and 50% is paid directly to the writer(s) of the track. This income is called “backend”, and is often the only payment you’ll receive for certain kinds of placements. This is common for libraries that don’t collect the individual sync fees for each composition. Instead, they’ll charge a customer a single “blanket fee” to access all the tracks in their library. The blanket fee is typically not shared with composers, leaving the composer only the backend as payment, unless there are any upfront fees as part of the deal.

Join and Register

So, what does it take to collect royalties from a PRO? In a nutshell, you join a Performing Rights Organization like ASCAP, BMI or SESAC and you ensure your music is registered with your PRO.

Public performance uses are tracked (and paid out) by the title under which the composition is registered. Any libraries that you have an exclusive contract with will be the ones to register your music with a PRO. They will list themselves as publisher in order to collect the publisher share, while you will collect the writers share.

Non-exclusive libraries that you contract with will register songs the same way, but they will use a new title that is unique to them. This allows them to collect publishing royalties for any placements they are able to procure. Oftentimes, the new title is a simple identifier added on to the song title. Say you provide a song titled “My Best Tune” to the non-exclusive music library “Great Songs”. Great Songs registers the song using the title “My Best Tune-GS”. If they get a placement using that unique title, then the publishing royalties will flow to them.

Royalty free libraries generally don’t partake in publishing income. Their focus is on non-broadcast placements that don’t generate backend. But, it’s also not unheard of to have an RF track show up in a broadcast situation. So I’d encourage you to also join a PRO as a publisher and to register your non-exclusive royalty free tracks with a PRO, listing you as writer and publisher. This will allow you to collect 100% of royalties. Registration is easily done online via your PROs’ website.

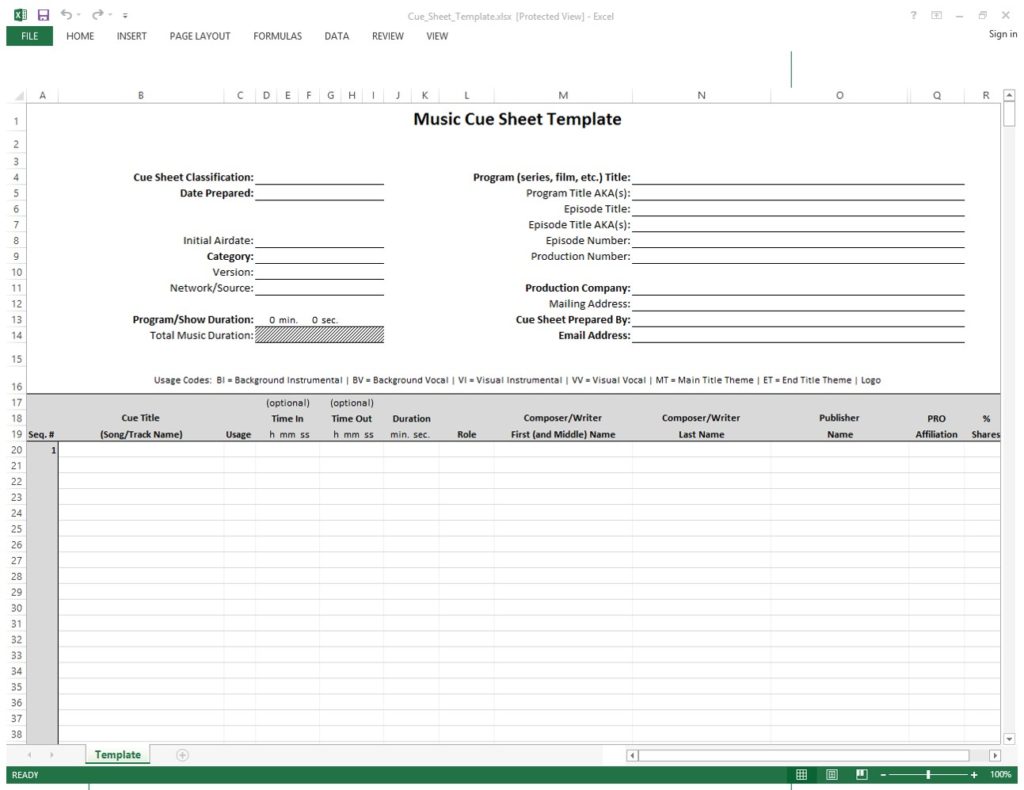

Cue-sheets

When used in a broadcast situation, your music will show up on a cue-sheet. A cue-sheet lists all the music contained in the project. It shows each cues’ title, duration and how it was used, whether as a “background instrumental” or “feature vocal” or whatever the case may be. The cue-sheet also includes the name of the writer(s) and publisher(s) and their ownership shares.

The cue-sheet is filed with the PRO by the music supervisor or production company working on the broadcast. The PROs pay out royalties based on the cue-sheets they receive, along with other factors. The cue-sheet system is not an exact science, and hopefully new technologies will increase accuracy in the future.

How Much Income Will I Make?

How much you can expect to earn in the library business is a difficult question. One way I can help to answer is by using my actual experiences. Let’s start with royalty free sales. Unlike placing music in film or broadcast productions, it’s a low cost, high volume business. You generally get to set you own prices in the RF market, and I price a full length track at $39.99. This is split with the library, so if you priced your music the same way, you’d make $20.00 on each sale.

What’s not helpful about that information is it doesn’t answer the question of how many sales a month you will make. But everyone’s situation is different and that question can’t be answered. Will you have a large number of tracks for sale? Will they stylistically be of genres that are known to sell best? You’ll just have to dive in, work the market and see how it goes for you!

What About Broadcast Sync and Master fees for Film and Broadcast Productions?

Earlier I wrote that there is no statutory rate for the amount of a Sync and Master fee, and it is negotiated by each library. A real word example I can share with you is a recent placement I had in a very popular premium cable TV show. My cue was used twice in the episode. The library charged them $1,400. Placements I’ve had in feature films for theatrical release average at $1,000 each. (Both of those examples are before the 50/50 split.)

Securing the rights to tracks from major, well-known artists can sometimes cost orders of magnitude more than this, so this is a niche that helps music supervisors stay in budget while finding perfect tracks for their needs and providing a meaningful source of income to writers of library music.

And the Backend?

I mentioned previously that the most typical broadcast TV placements are cable TV reality shows. See the table below for actual backend payouts reported on ASCAPs’ most recent domestic performance statement. To demonstrate the different possibilities, I’ve included a variety of networks, airing times and cue lengths. Each entry represents a single play.

| Network | Type of Performance | Time of Day the Show Aired | Length of Music Aired | Amount Paid |

| History | Background | Night | 0:14 | $0.77 |

| Background | Primetime | 0:14 | $3.09 | |

| Background | Afternoon | 0:13 | $2.15 | |

| HBO | Background | Night | 0:13 | $1.02 |

| Background | Primetime | 0:13 | $4.12 | |

| Background | Morning | 0:13 | $2.06 | |

| Discovery (Planet Green) | Background | Morning | 0:28 | $0.51 |

| Background | Afternoon | 0:28 | $0.76 | |

| Background | Primetime | 0:28 | $1.01 | |

| Hallmark | Background | Morning | 1:54 | $6.30 |

| Background | Afternoon | 1:54 | $9.44 | |

| True TV | Background | Primetime | 0:07 | $0.88 |

| Background | Afternoon | 0:07 | $0.66 | |

| Background | Night | 0:07 | $0.22 | |

| The Learning Channel | Background | Afternoon | 0:53 | $12.97 |

| Background | Primetime | 0:53 | $17.30 | |

| Background | Night | 0:53 | $4.33 | |

| TNT | Background | Primetime | 0:41 | $37.71 |

| Background | Night | 0:41 | $9.42 | |

| Animal Planet | Background | Morning | 0:16 | $0.67 |

| Biography | Background | Morning | 0:26 | $0.41 |

| Viceland | Background | Afternoon | 2:25 | $9.01 |

| National Geographic | Background | Night | 0:17 | $0.40 |

You can see that how much you might earn in a quarter is dependent upon a lot of factors, and of course the volume of placements.

Streaming Amounts

As entertainment options move from cable to the streaming services, the backend payments are taking a serious hit. The entries in this table represent a single episode of three different shows as streamed on three different services.

| Streaming Network | Type of Performance | Number of Streams | Length of Music Aired | Amount Paid |

| Amazon | Background | 16,890 | 0:17 | $0.20 |

| Hulu | Background | 123,612 | 0:08 | $0.41 |

| Netflix | Background | Not reported | 0:15 | $0.68 |

Yes, it really is accurate that 123,612 streams of an eight second cue paid out .41 cents. Hulu reported 68 separate entries on the statement that all totaled added up to $17.36. While streaming may be the future, as it stands now streaming backend payments are not a viable source of income.

Summary

Creating and monetizing your music can be a long and drawn out process, but there is such a sense of accomplishment in persevering to the point of achieving successful placements that keep you going.

One great feeling is knowing that your creation was selected out of the hundreds of thousands tracks available. Another is realizing that millions may have heard something that you have imagined from scratch—and possibly created in your bedroom! Just remember to be smart in crafting your deals, and know about the industry norms and the kinds of payments you may be entitled to.

Please note: When you buy products through links on this page, we may earn an affiliate commission.

[…] http://sonicscoop.com/2019/05/22/making-money-with-library-music-the-details-of-the-deals/ Making Money with Library Music: The Details of the Deals […]