New Gear Review: The BAD8 A/D Converter from Burl

I don’t write a lot of reviews, so when I do, I like to make it about something I have an opinion about. As such, this review of Burl‘s newly-minted conversion card, the BAD8, will take a slightly different shape than normal. The flowery, qualitative side of gear reviews can suck to read, so let’s cover the basics before we get into opinions.

Features

The BAD8 by Burl represents a unique breed of analog-to-digital conversion, offering a fully-discrete, transformer-balanced, class-A build.

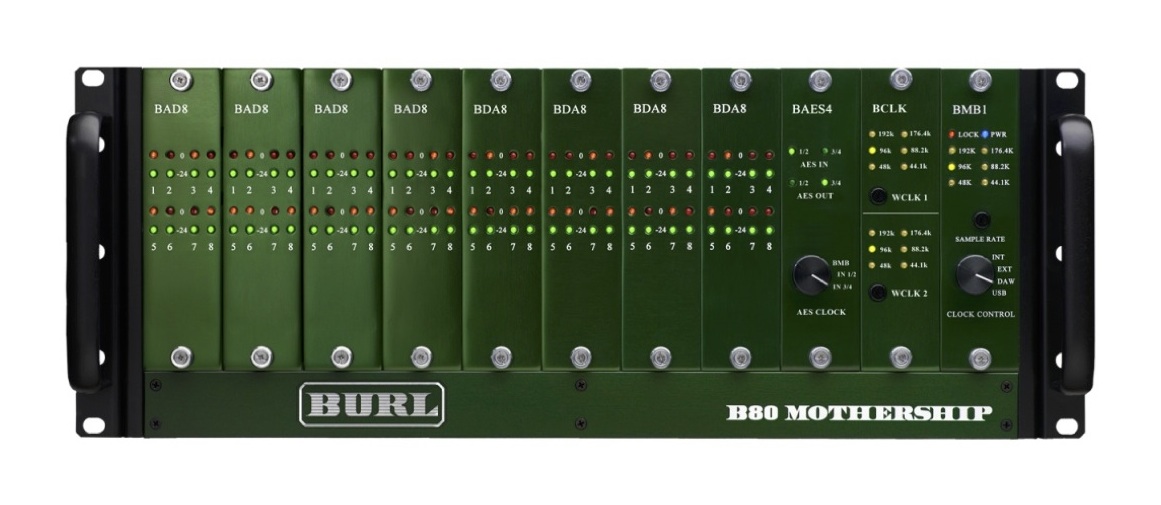

The BAD8 is an 8 channel analog-to-digital converter in Burl’s familiar proprietary card standard, for use in either of their available Mothership chassis: The 10-slot B80 or 2-slot B16. It is 24-bit PCM and supports the usual sampling rates for modern digital pro audio, 44.1 kHz -192 kHz.

Continuing in their spirit of design, the BAD8 is a transformer balanced, class-A, fully discrete circuit with a perspective. Burl has figured out a way to shrink the form factor of their signature BX1 transformer, so now they can pack 4 more channels on one board but it’s still that Burl thing.

And what exactly is “that Burl thing”? As with past designs, Burl has aimed to create a converter that’s as clean as anything when run at conservative levels, but has the potential be pushed on the way in for some gentle transformer saturation, which makes a Burl-equipped DAW feel and respond bit more like a high-end analog medium than a digital one.

The amp circuit redesign around the new ADC chipset rendered an even lower latency as well. Interestingly, there are 4 filter options present on the circuit, accessible from a jumper on the PCB. There are 3 different anti-aliasing filters, each resulting in a subtly different sound and slightly different latency.

Burl also provide you with the option to bypass the DC offset high pass filter. Combining this with the fact that there are no capacitors in the signal path, you could get some properly speaker-thrashing low end captured in your DAW of choice. (Though Burl cautions against this setting if you intend to process the recording further in the digital domain, unless you are careful and intentional with high pass filters as you go into the mix.)

In Use

Installation of the BAD8 into the Mothership is easy. The cards themselves are beautifully made and substantial; everything you touch feels sturdy and considered. The BAD8 slides nicely through the guides in the chassis and is held in place with knurled thumbscrews that also have star bit heads on them, which is a dope touch. One additional header connection is required between the main daughter card and the cosmetic front panel, but that’s basically it.

Input is presented at the back of the BAD8 on a Tascam standard DB25 scheme, as well as trimpot adjustments for operational reference level. The front panel loses the multi-segment meters present on the BAD4 in favor of the same metering scheme as the BDA8, a variable-brightness LED for signal indication and another for clipping.

If you are an existing Burl user, the BAD8 is compatible with a system that includes BAD4s as well. This is one of the underlying reasons for the additional filter options. Per the doc that ships with the unit, “The BAD4 has a fixed delay (latency) from the analog input to BMB output of 66 samples, whereas the BAD8 delay is configurable from 7 samples to 66 samples.” This is obviously great news for folks that want to expand a current system rather than scrapping all their existing AD cards for the newer BAD8s; simply choose the correct jumper position and you’re good to go.

There are some conventions that you’ll need to observe, however, and fair considerations as you plan any upgrades centered around adding BAD8s to an existing rig with BAD4s in it. If you are an early adopter of the Mothership, your BMB motherboard may need an update.

Fortunately, Burl is generously offering amnesty upgrades to users with BMB motherboard cards in the serial range of BMB1-0428 and above, and BMB2-0176 and above. Older BMBs with serial numbers that predate this will require a paid upgrade. They’ve informed me that this will be $899, which is very reasonable considering that’s less than half the cost of a new rack. Also, considering the way our industry generally mothballs out-of-date digital equipment, the availability of this upgrade speaks deeply towards their ethos of modularity in design and their willingness to provide support to their user base.

One additional consideration if you are adding BAD8s to an existing rig with BAD4s in it is the way the B80 backplane itself handles channel assignments. Basically, now that there are two options for the number of channels present at each input card, the BMB needs to have a way to distribute that information from the backplane to the ultimate digital outs of the rack. To that end, the updated BMB has a jumper set that allows you to define the inputs and outputs present at each card position and thus also the channel numbering scheme.

Being as I am primarily a Pro Tools user, I will limit the configuration conversation to that usage case for now. In a rig that has mixed BAD4s and BAD8s, Burl recommends you split the two different converter cards across the two different output ports on the BMB1.

So, imagining a case where you want the entire B80 filled with input conversion only, the first four slots would be dedicated to the BAD8s and the remaining 6 would be dedicated to BAD4s. For example, Digilink Port 1 would have slot 1 allocated for channels 1-8, slot 2 for channels 9-16, slot 3 for channels 17-24 and slot 4 for channels 25-32. Digilink Port 2 would then switch to 4 channels per BAD4, with slot 5 allocated for channels 33-36, slot 6 for channels 37-40, and so on, through to slot 10.

The Pro Tools Digilink standard has a fixed limit of 32 channels per connector, so the BMB1 and B80 splits them asymmetrically like this. The good news here is that BAD4s will still work in any of the first four card slots; you simply won’t have any audio present at the last 4 channels in any given card slot. However, this can easily be routed around in the Pro Tools I/O setup to make the numbering appear sequential inside Pro Tools. This is yet another cool example of Burl’s commitment to modular design and the end user’s ability to define their configuration based on individual needs.

For example, if you are an existing Burl user with 16 channels of I/O (4x BAD4s and 2x BDA8s) and wanted to add an additional 16 channels of BAD8s, the 2x BAD8s go into slots 1 and 2, the 4x BAD4s go into slots 5-8, and the 2x BDA8s go into slots 9 and 10. In this example, the 16 channels of input from the BAD4s and 16 channels of output from the BDA8s present at Port B on the BMB1 and you’ve got a smoking 32 in, 16 out rig on two Digilink ports, with room to add another 16 inputs as requirement dictates.

OK, yes, great, but how does it sound? I feel a story is in order as we get into the sonics of the thing. There’s so much rhetoric, opinion, and hyperbole in the space of musical equipment that I wanted to try to do this review more quantitatively, if possible. The opinion of someone whose work you may not know and whose musical tastes my differ from your own always feels like a fairly useless metric to me as a reader, and so I wanted to try to offer you something better.

I should also say here that I am already a Burl user. Given that fact, I felt that it would be disingenuous to try to represent my opinion as objective without some underlying factual reasoning. I already like their stuff enough to spend my money on it and to base my workflow around it. In fact, one of the reasons I took this review on was because I selfishly wanted to hear it to consider what is likely to be an inevitable purchase for me.

However, honestly, I never wanted to like Burl’s stuff. I wasn’t the biggest fan of the 2192, and I thought some of the conversation surrounding the Burl line sounded a little shtick-y.

Also, I came up in SSL rooms where the mentality was always to put lot of color in the racks but unify the center of the signal chain with something more on the transparent side. As such, I leaned into that same mindset in designing my hybrid situation; less color as the backbone of the signal path with tons of colorful options at the ready—but only when you want them. It seemed a little strange to put that much color into the conversion. After all, isn’t conversion the true center of the signal chain in most studios now? Isn’t linearity what you are supposed to want in a DAC?

So, here’s where the story comes in. I was hanging with my friend Justin Melland the other day, checking out a new synth he had just snagged. He is a very busy film composer here in LA, carving out a cool lane in a crowded marketplace. He has 2 monstrously large Eurorack cases, as well as a BEMI skiff with a modern clone Buchla 259 complex oscillator, and that crazy Macbeth Instruments thing that’s kind of like a SynthiA.

But Justin’s most recent acquisition smoked everything in the room. It was one of Rob Hordijk’s 5U format modulars. I have a pretty sick synth collection here too, but this legit got me jealously googling immediately. There was just something intrinsically right on about this thing. The raw oscillator sound even without the filters involved was massive and every time you turned a knob, you found yourself in a whole new beautiful landscape. It was as if this thing was actively helping.

The day after our hang, Justin actually reached out to Rob to try to get some quantification from him as to why it was just so euphonious, and Rob sent back one of the most beautifully thoughtful emails I’ve ever seen. They have been generous enough to let me excerpt some of it below, and I think it’s a wonderful jumping-off point for the conversation about the sound of the BAD8. Per Mr. Hordijk:

“Millions of years of evolution have caused the development of the human hearing mechanism [to be] the way it is, with the sole purpose to be able to survive in nature like it was when we were still cavemen. One hundred and fifty years of industrial sounds have not been able to change that. So, I think that some understanding of these natural principles of human hearing are important when designing electronic music instruments, as the psychoacoustic aspects are so all important.

“My design philosophy is that designing an electronic music instrument is a process that happens on a line between pure science at one side and pure art at the other side. Scientists have the disadvantage that they must always adhere to the ‘scientific method’, while artists are sort of expected to stay away from anything formal. But as a designer, one has the freedom to smoothly glide over this line and take whatever one needs from science and from art. So, when designing, I start quite formal with algorithms based on solid physics and math. But then it needs to be tweaked by ear as human hearing is not at all linear, so I go to psychoacoustics, and my own ears, to tweak the circuitry until it has the sound I like. Hoping that others will also like the sound.

One of the main principles is that when applying a nonlinear operation on a sine wave, this will ‘distort’ the sine wave, causing new sine wave partials to appear. In fact, the original sine wave does not get distorted as it will still be present, it is only that new partials will be produced and added to the original sine wave. [As such], the result of the addition does not look and sound like a sine wave anymore. And for a complex waveform, this goes for each sine wave partial present in that complex wave.”

It would be reasonable to wonder why we’re talking about synthesizers in a review about digital audio conversion, but stick with me for a moment and I think we may arrive at something more interesting than a set of complimentary superlatives.

As I approached the simple experiments I wanted to try with the BAD8, I was looking to the writing of Bob Katz, and cats like that. Much of the focus in Bob’s writing is how distortion enters into the signal chain in a digital system and righteously so, the march of technology with regards to recording media and transduction for the past hundred years has been mostly towards linearity.

Each new format is successively endeavoring to improve on some of the inherent limitations of recording media; either incrementally inside the format of the day or by inventing a new form entirely. From wire to magnetic tape to PCM digital and beyond, the pursuit of more and more linearity has often been priority.

In Use

Since the BAD8 is intended as an alternative to the existing BAD4 which already enjoys such a fanbase, I thought a useful and simple experiment would be a null test. Basically, record a single source through both converters, phase invert the recording from one of the two and add them back together. Theoretically, this should describe any timbral difference between the two circuits. If they are identical and phase locked, the resultant sum of the two recordings should be a full null. If there are differences, the frequency bands that remain uncanceled should show those differences clearly.

In order to set up this experiment, I decided to use a simple electronic waveform rather than an acoustic source. Synthesized waveforms have a more rigid mathematical expression quite unlike a clarinet or a cymbal, and so would be easier to observe the expected result. Additionally, by removing some of the timbral variation inherent to human performance, the experiment becomes more repeatable.

The waveform source was my vintage Model D Minimoog. I used only 1 oscillator with no modulation, set to the first square wave. (In my understanding, this is supposed to be the closest to a 50/50 duty cycle and so the relationship of the harmonics should follow the Fourier series for the expected harmonics of a square wave.) This was then patched out to my most frequently used DI here, a modified Ampex 351 wherein the tape playback path of the signal chain has been modified by a genius tech friend to be a DI instead of useless electronics and an unused set of windings on the transformer primary.

The output of the 351 DI was then patched into a passive mult, in this case, Redco’s Passive DB25 multi in my patchbay. The output of the mult was then fed into both a BAD8 and a BAD4.

I decided that it would be most interesting to use the new filter in the BAD8 (the one Burl chose for default operation) because it was their favorite in the bunch, and that this would provide folks like me who are already Burl users with a clearer picture of the timbral differences between the BAD4 and the new kid on the block.

I then recorded a sweep on the Moog, starting with the filter fully closed and sweeping to fully open. I chose a low fundamental pitch as I figured this would provide us with more information about the upper partials because more of them would exist in the audible range. As such, the completeness of the phase cancellation across the spectrum should theoretically be more perceptible.

The differences in latency were clearly observable in the waveform display, but the absolute phase was easy to see. I then nudged the recording by sample until the waves lined right up, flipped the phase and checked the two recordings of the same filter sweep out of phase with one another. The resultant sum wasn’t a complete null but it is surprisingly close. On my test rig here, the loudest band was 36 Hz (on a piano, D1). This frequency showed persistent range of -27.2 DBFS averaged across the sweep, however the persistent range dropped more than 30 dB to -62.4 DBFS with the two converters’ outputs phase inverted and summed. You can click here to download some session files and examine how completely they cancel for yourself.

Armed with this knowledge alone, I feel confident in saying that these converters are continuing in the Burl tradition of quality, and that if you already like the Burl sound, these are a welcome addition to the family that increases channel density without sacrificing sonics.

However, this is also where the experimental premise starts to go a little pear-shaped.

Observing the waveform output from the Moog’s signal path into the DAW on a spectrum analyzer (in this case, iZotope’s Insight), it was immediately apparent that the harmonic series was not at all what was mathematically expected. However, the Moog’s sound is legendary and this DI has smoked everything I’ve ever put next to it… does that mean that the non-linearity observed in the Moog’s square wave is a bad thing? Not according to the legions of frothy devotees. Does this mean that the non-linearity inherent to the circuit design of these Ampexes is an inherently bad thing? Not when they win almost every time over the several other similarly awesome DI’s I have in this room.

So in the above session, you’ll find the audio sweeps from the Minimoog through three sets of conversion: the BAD8, a BAD4, as well as an Apogee AD-X. Try playing with the phase! If you have an all-pass filter like the Little Labs IBP or Waves In-Phase, you can try some more subtle shifts. If not, a simple EQ1 with phase invert engaged will describe the timbral differences and phase coherence of the 3 units.

Observation with a soundfield analyzer can also be a cool way to reference the results! Additionally, you’ll find a song in there (Hurricane Walkin’ by Heather Christian and the Arbornauts) that went through 10 loops of conversion through each of the aforementioned converters. This helps evince the color of each box through the additive effect of multiple stages of conversion, as well as the multiplicative effect of more subtle shifts in absolute phase. I tried to align these in the time domain (using a two pop), but try nudging them by sample and messing with phase as well to see if you can get even more phase cancellation.

This is where Rob Hordijk’s missive above becomes pertinent. Even though the Moog’s square wave is ”distorted” in terms of its relationship to the mathematically expressed Fourier Ideal, the Moog square is one of the most widely recorded and well-loved square waves in history—and that’s because the Bob Moog brilliantly toed that line between art and science.

Similarly, with Rob’s synth, the moments at which he followed his taste past the point of accuracy seem to define the instrument. While there may be compromises or inherent distortion in the circuit design, it all serves to make a product that sounds better to the flawed mechanism through which it is perceived: the human ear.

So, I began to wonder if thinking of digital audio conversion being most well-served as a linear expression of mathematical accuracy is potentially wrong headed, too. My own initial misgivings about the sonic footprint of a so-called “colorful” centerpiece to the digital framework of my DAW were immediately assuaged by hearing the Burl line—so much so that I immediately upgraded my rig to as many Burl channels as I could afford. After all, the most highly prized pro audio gear in all of our wish lists isn’t flat with regards to frequency either; far from it.

When was the last time you put up a measurement microphone in front of a vocalist? When was the last time you mixed something entirely in the box without adding some kind of distortion? Be it the subtle harmonic distortion inherent to analog modeling-style plugins, tape simulators, or overt gain stuff, everyone I know that mixes at least a little bit in the box leans into distortion. I know I haven’t turned out a mix in years where there isn’t at least one Decapitator hanging out.

Given all that, would you rather have a room tied together by a device that faithfully reproduces everything that goes into it, or is it more desirable to have a centerpiece that has a flavor that is intrinsically right on? Is the BAD8 a bang straight, perfect reproduction device? Not necessarily! Does that matter when it makes everything that goes through it sound better? Well, I’m about a year into being a Burl user and I’ll never go back. If you have a chance to hear it, I’d be surprised if you didn’t seriously consider making the upgrade as well.

In my opinion, the whole Burl lineup is one of the best made and most fabulously euphonic converter product lines on the market today, at any price. Even though the Mothership is the digital center of my studio, it feels more like the last analog step than the first digital one. Similarly, in keeping with all the best analog kit we prize, you might also be happily surprised by the cleaner side of its color spectrum as well, if you choose to not lean into transformer saturation. In operation, it’s much closer to the idea of “color when you want it” than you might expect.

MSRP for the BAD8 is $2,699, up from the BAD4’s street price of $1,499. However, the additional channel density on the BAD8 represents a 10% savings for the same amount of throughput if one were to use BAD4s instead. The higher channel density of the BAD8 also makes 32 I/O possible on a single Digilink port, so there are some additional savings to be had in the backplane in larger systems. Furthermore, this means that 64 I/O is actually possible on one HDX card if you fill two B80s with 32 channels each.

This is good news for folks that still want to do large format analog mixing or recording and have the scratch to go fully Burl but don’t need the extra processing power from an additional, potentially extraneous HDX card.

Simply put, I see the BAD8 as a very welcome addition to an already awesome product line that makes it easier to maximize the I/O available in a single B80.

Brian Bender is a Los Angeles based Producer, Mixer, Composer and Sound Designer with 15 years of experience across almost every segment of music and audio production. His work has been nominated for 2 Grammys, 2 Independent Spirit Awards and an Oscar.

Please note: When you buy products through links on this page, we may earn an affiliate commission.