New Software Review: StageOne and CenterOne by Leapwing Audio

When I got the chance to review Leapwing Audio‘s StageOne and CenterOne plug-ins, my heart widened with excitement. Why the horrible pun? Two reasons:

Leapwing Audio aims to inject some magic into your stereo field with the StageOne and CenterOne plugins—can they find a place in your arsenal?

Firstly, these plug-ins operate on the stereo field: they alter width, influence front-to-back depth, and facilitate surgical manipulation of each channel, be it left, right, or center.

Secondly, I’m obsessed with finding good digital width processing. Or rather, I became obsessed when I sent my favorite hardware piece back to Rupert Neve Designs for some maintenance.

I found myself stuck without my trusty Portico II MBP for two weeks, and yes, I deeply felt its loss. Nothing I tried in the digital world seemed to give me the same breath of fresh air that the MBP could with just a single click of its built-in stereo width processing. If such a thing were to happen again, I’d want to make sure I’m in good digital hands.

So, are these two plug-ins the answers to all of my problems? Let’s find out.

Features

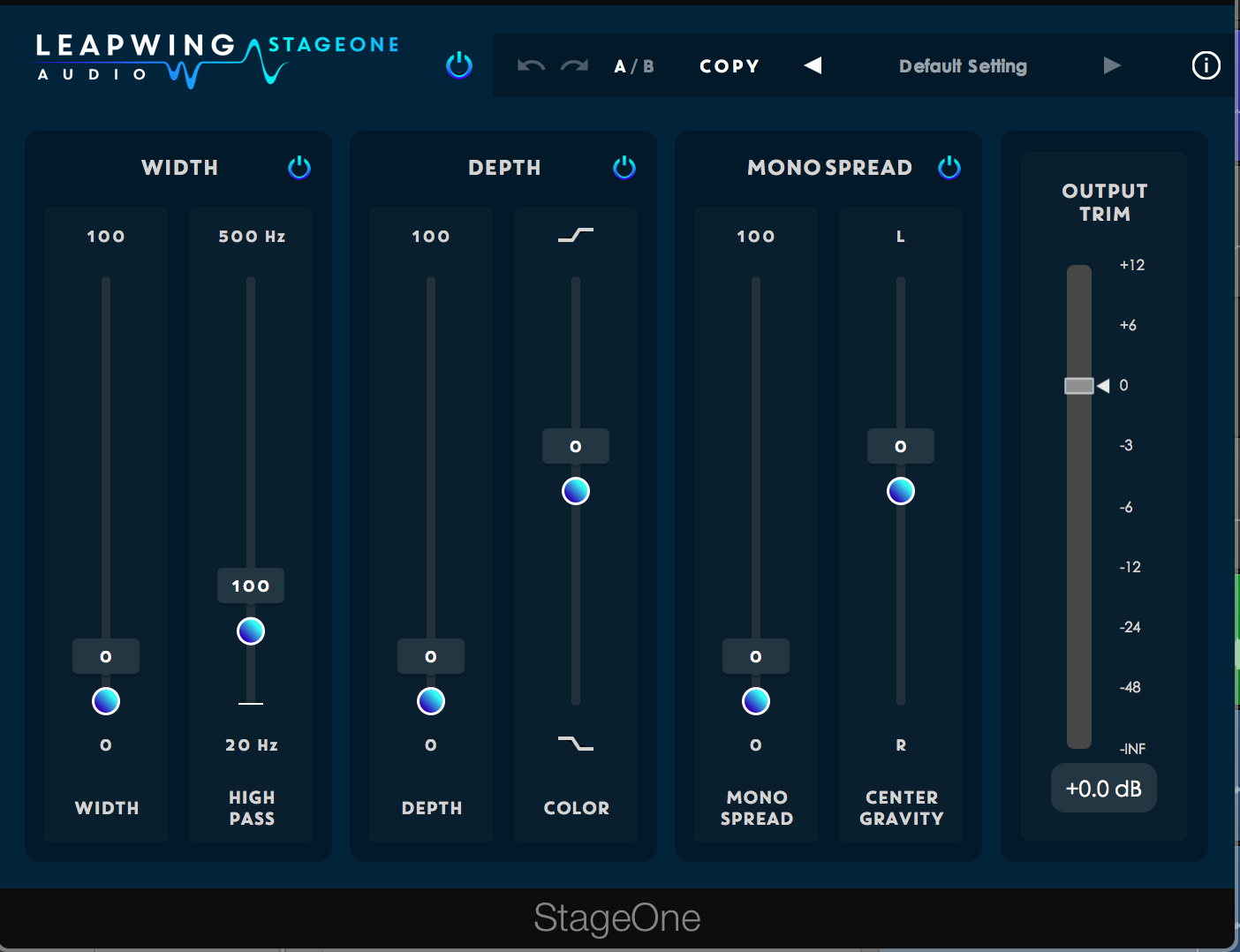

StageOne offers a relatively simple GUI, with three main sections: Width, Depth, and Mono.

You get two sliders per section—and that’s pretty much it for controls. The Width slider is self evident: it stretches the apparent width of a source. The other is your high-pass filter, below which no widening occurs.

You get two sliders per section—and that’s pretty much it for controls. The Width slider is self evident: it stretches the apparent width of a source. The other is your high-pass filter, below which no widening occurs.

Mosey on over to the Depth section and you’ll find Depth and Color controls. The former adds reflections to the signal, pushing elements back into the overall mix. In a master, they can help create a heightened feeling of front-to-back depth. The second slider tilts this effect into either higher or lower frequencies; it’s a tilt EQ for the reflections.

Mono comes next, with a slider to stereoize monophonic content, as well as a Center Gravity control to push the signal towards the left or right of the stereo field (basically, it’s a panner). You can bypass any section individually. An output trim rounds out the affair.

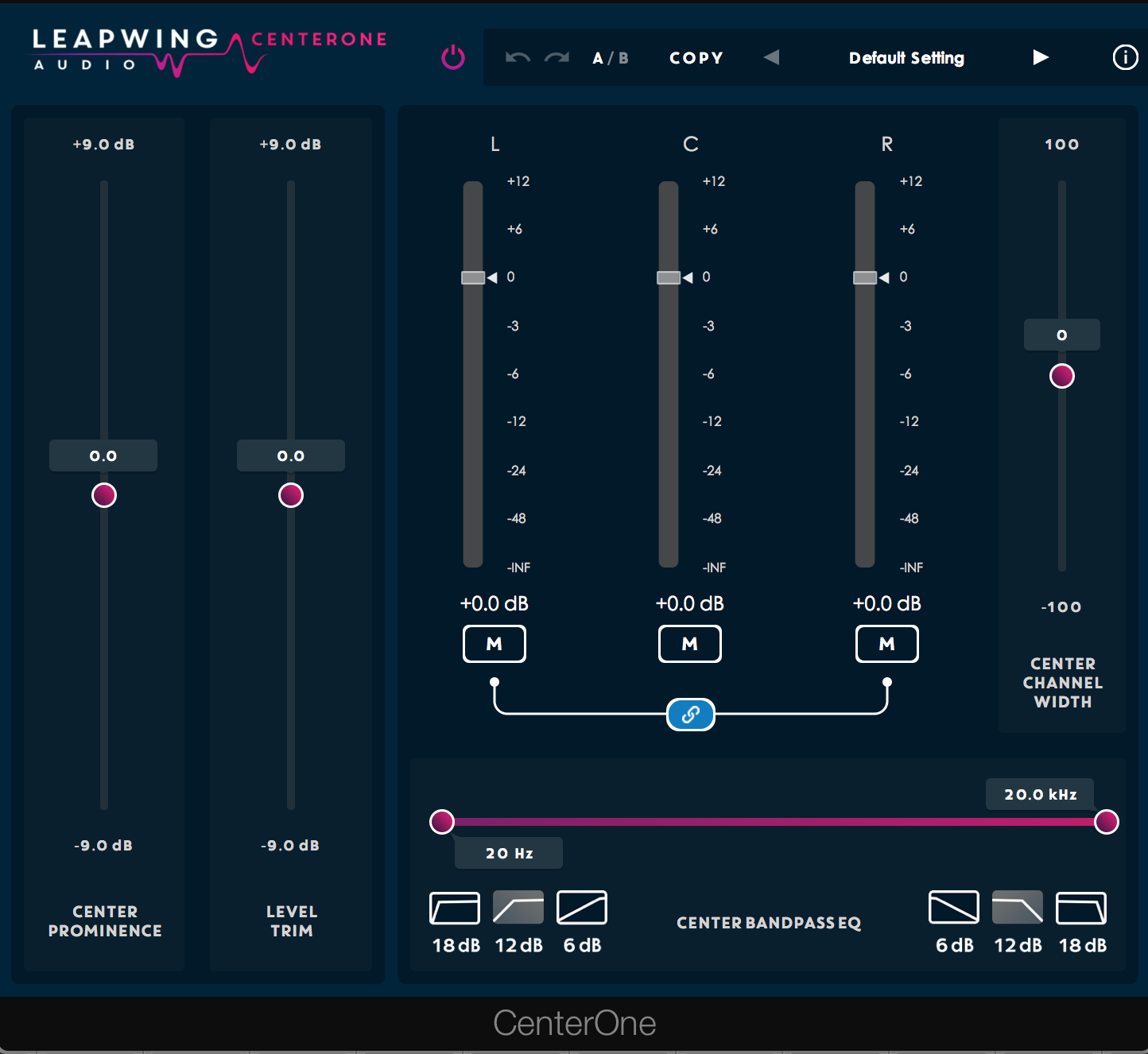

CenterOne’s interface seems simple, but the GUI facilitates some esoteric operations: see those L, C, and R sliders? Those are level controls for the left, center, and right signals of your stereo mix.

CenterOne’s interface seems simple, but the GUI facilitates some esoteric operations: see those L, C, and R sliders? Those are level controls for the left, center, and right signals of your stereo mix.

Look below the sliders: that’s a filter for eking out or emphasizing frequencies in the center channel. If you’ve got an annoying frequency bloom in the phantom center, you can assign it to the center channel and edge it back into the mix; because CenterOne is not an M/S processor, it won’t sound like M/S equalization.

Ostensibly, the plug-in uses a combination of panning and spatial-manipulation DSP to isolate the information in the left, right, and center independently. What’s more, CenterOne combines everything into a bit-perfect signal at the output—it will null against an unaffected copy when left in untweaked.

Note the Center Prominence and Center Channel Width sliders; we’ll get into how they work in the next section. A level trim is also on hand.

In Use

Remember that Mid/Side is a misleading term. A better phrase is Sum/Difference. It’s left + right / left + phase-inverted right. Why does this matter?

Say you’ve got a guitar mixed into the left speaker alone. Engage M/S processing, and you’ll wind up tweaking the guitar in both the M and S channel. This can lead to weird timing issues (in the case of compression) and weird tonal issues (in the case of EQ).

As CenterOne isn’t an M/S processor, you should be able to processes material in the left speaker without affecting the vital center.

But what about off-center instruments?

This is where the Center Channel Width control comes into play—take this example, from the tune “Fun Fax” on Adjective Animal’s upcoming record, “America’s Got Talons”.

I’d like to boost the vocal at around 400 to 600 Hz for a little umph:

But I also want to edge these frequencies out of the guitar in the right channel. I want to divert your attention from the guitar and redirect it to the lead vocal. With M/S processing, I can’t be as exact as I’d like:

The problem lies in the guitar: it’s not fully right, but off-center, so we still have guitar competing with vocals in the mid channel. When I boost in the mid channel, but cut in the sides, it creates a complicated EQ conundrum.

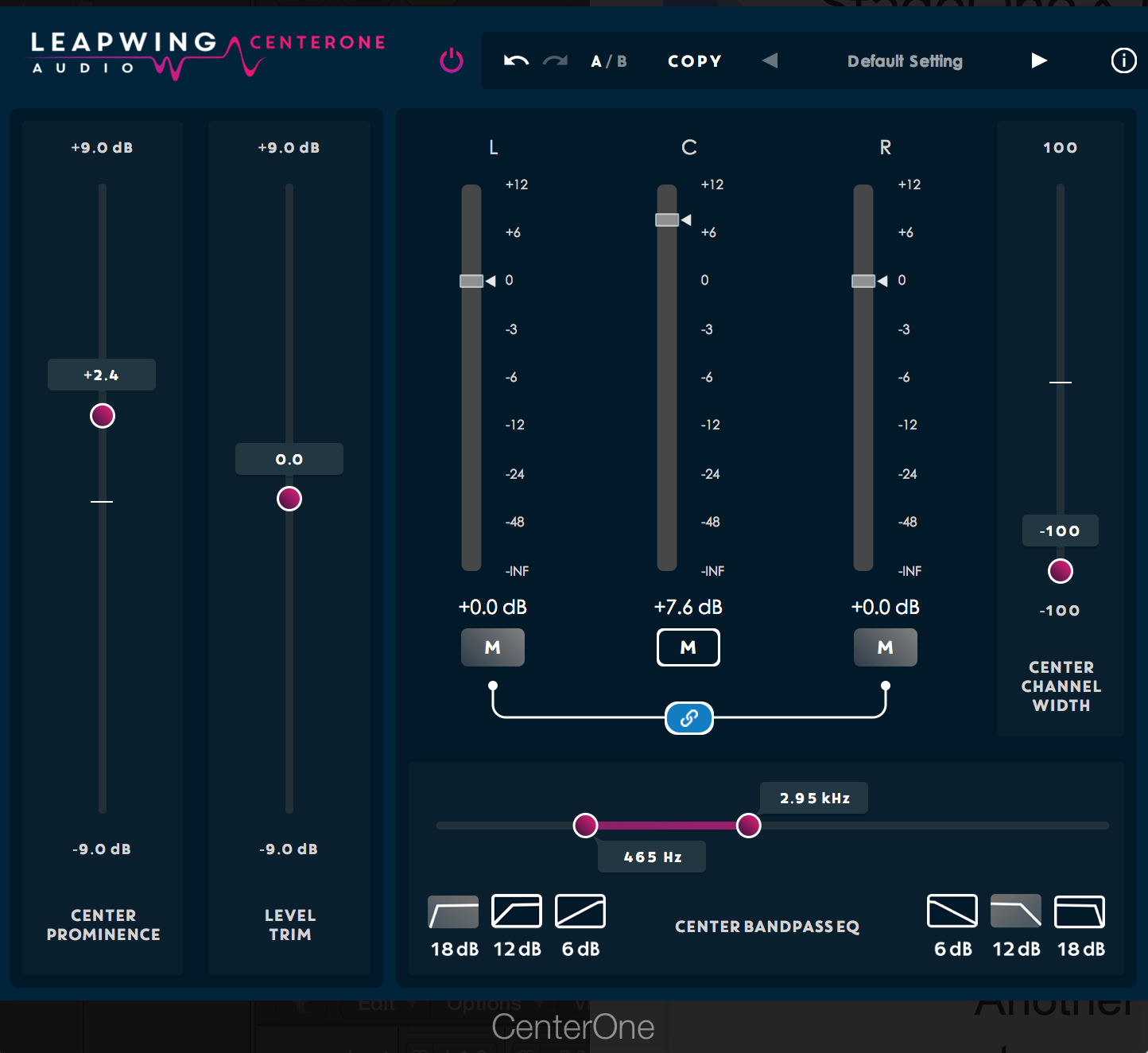

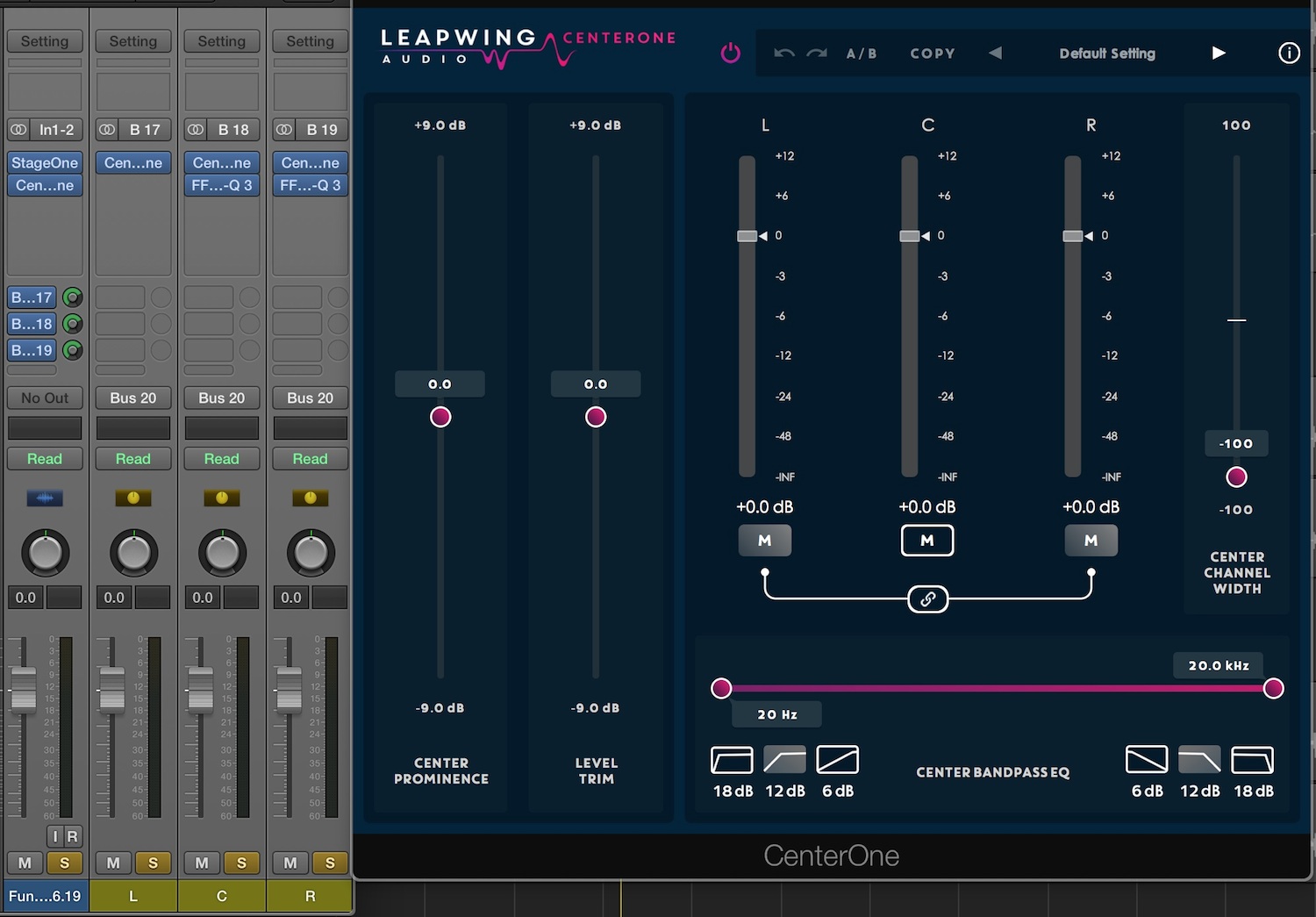

With CenterOne, the routing is complicated, sure, but I can get more surgical with my EQ: look at how we handle the routing in this screenshot:

Note the position of the Center Channel Width slider: this control shows the algorithm how to define mono content, essentially “filtering out” more and more off-center material the lower you pull the slider. Since we’ve taken the Center Channel Width slider down to -100, there’s nary a guitar in the center.

Note the position of the Center Channel Width slider: this control shows the algorithm how to define mono content, essentially “filtering out” more and more off-center material the lower you pull the slider. Since we’ve taken the Center Channel Width slider down to -100, there’s nary a guitar in the center.

So, I take my M-channel boost and apply it to the center channel. Next, I take my cuts and lay them on the right channel. Here’s what we get.

Go back and forth between these audio examples and listen. You won’t hear an obvious boost to the vocal. Instead, you’ll find the guitar is slightly less noticeable—less prominent. Your attention has been successfully diverted.

If your ears tell you these examples sound the same, well, here’s the null test:

It’s not a perfect null. Instead, we’re (mostly) left with the information I wanted to avoid: the prominence of mid-rangy guitar in the center channel.

For mix-buss testing, I chose two tunes: a vibey analog mix (again, from Adjective Animal), and an acoustic number from Americana singer/songwriter Pete Mancini. You might recognize these tunes from my DynOne review; we’ll actually leave the DynOne processing on and start from there.

Here’s the first tune, called “Everybody Hide”:

Let’s see what happens with StageOne. Settings are 40% width, with a high-pass at 339 Hz.

It’s quite seductive, but if you listen for a while, it begins to feel flattened, stretched, and weird—a problem endemic to extreme width processing. So let’s set it back to 17% and hear how it sounds.

I find the results pleasant but subtle; bypass it, and you miss it when it’s gone.

What would depth add? Here’s 100 percent, tilted in color toward the highs:

There’s way too much going on here—the reflections are not only noticeable, but distracting.

In my testing, I found less depth is frequently better on full mixes, though small amounts do add some useful interplay between the back and the front of the mix. Here’s the tune at 4%.

Let’s move on to complementary CenterOne processing.

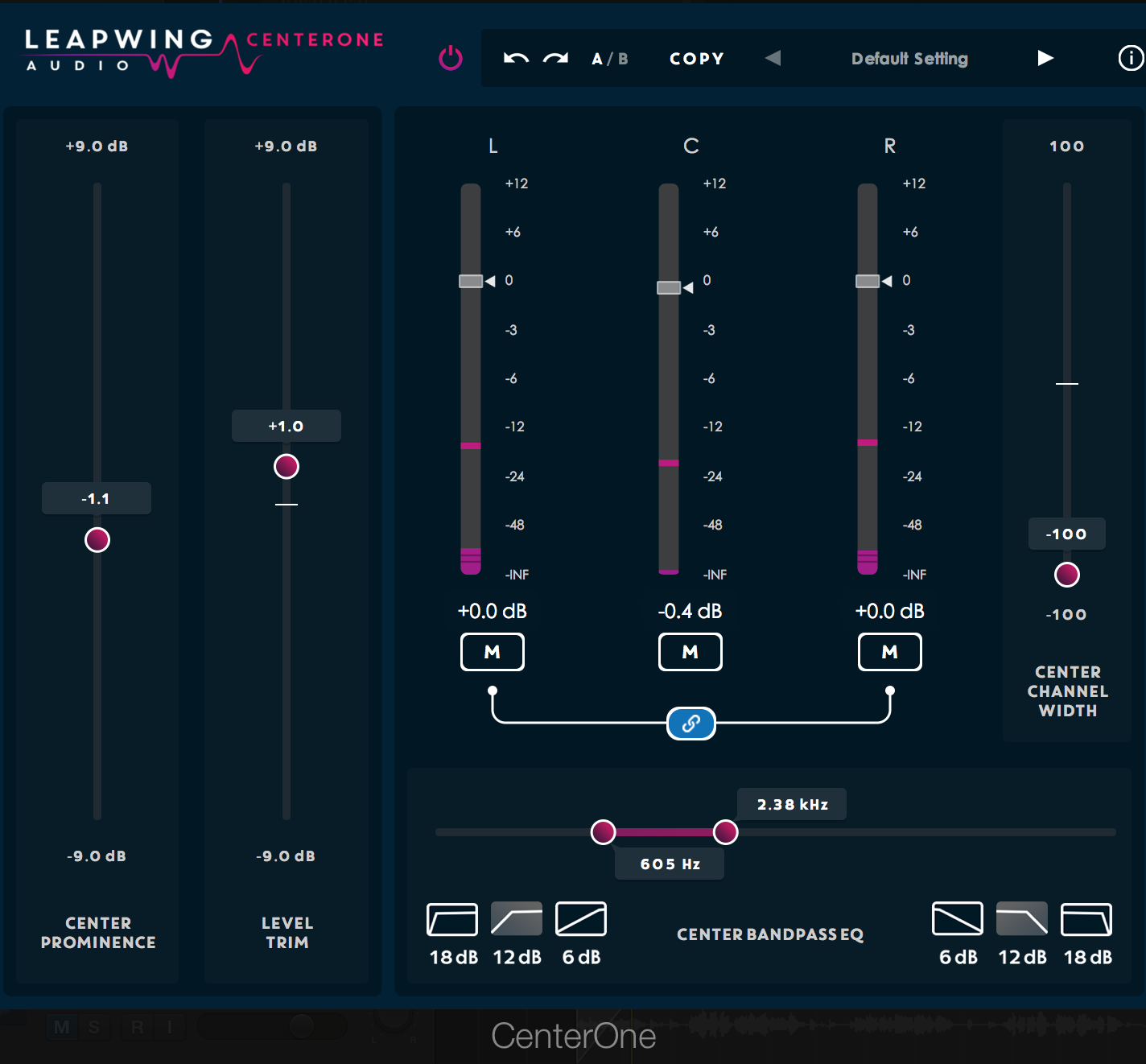

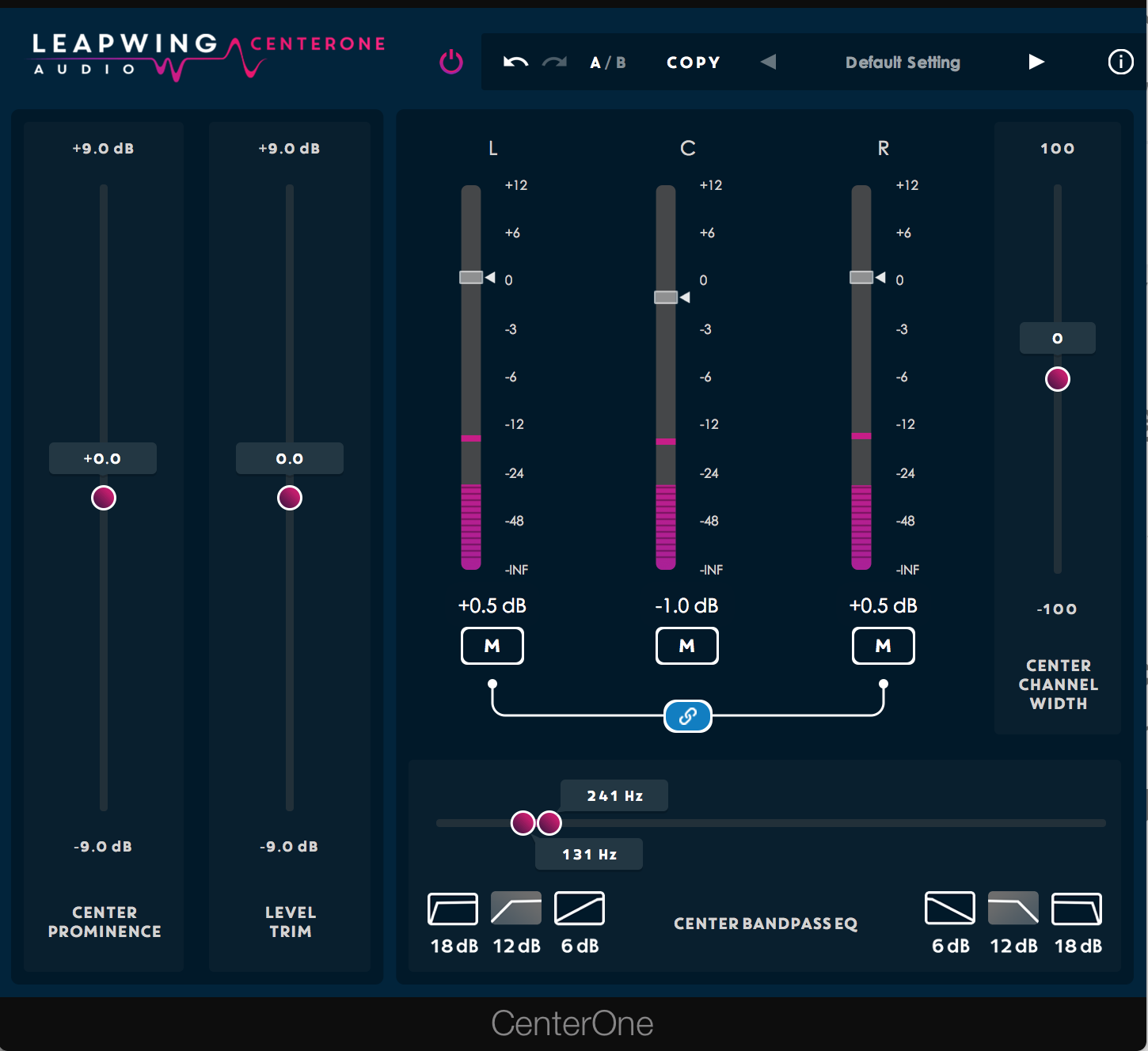

As you can hear, the bass pokes out a bit. We’ve already got DynOne and StageOne handling tone, compression, and width. With CenterOne, we can tamp this low-mid bloom down with the following settings:

And if we top it all off with 0.8 dB of Center Prominence, we can find a happy medium between stereo width and center solidity. That’s exactly what the Center Prominence slider is for: raising or lowering the level of your mix’s phantom center.

And if we top it all off with 0.8 dB of Center Prominence, we can find a happy medium between stereo width and center solidity. That’s exactly what the Center Prominence slider is for: raising or lowering the level of your mix’s phantom center.

Let’s go to our acoustic tune, “Pine Box Derby”.

This mix is a little mono-centric. I tried the Mono section first, but it added a woozy feeling to the vocal that made it sound auto-tuned on certain phrases. So, no mono was employed.

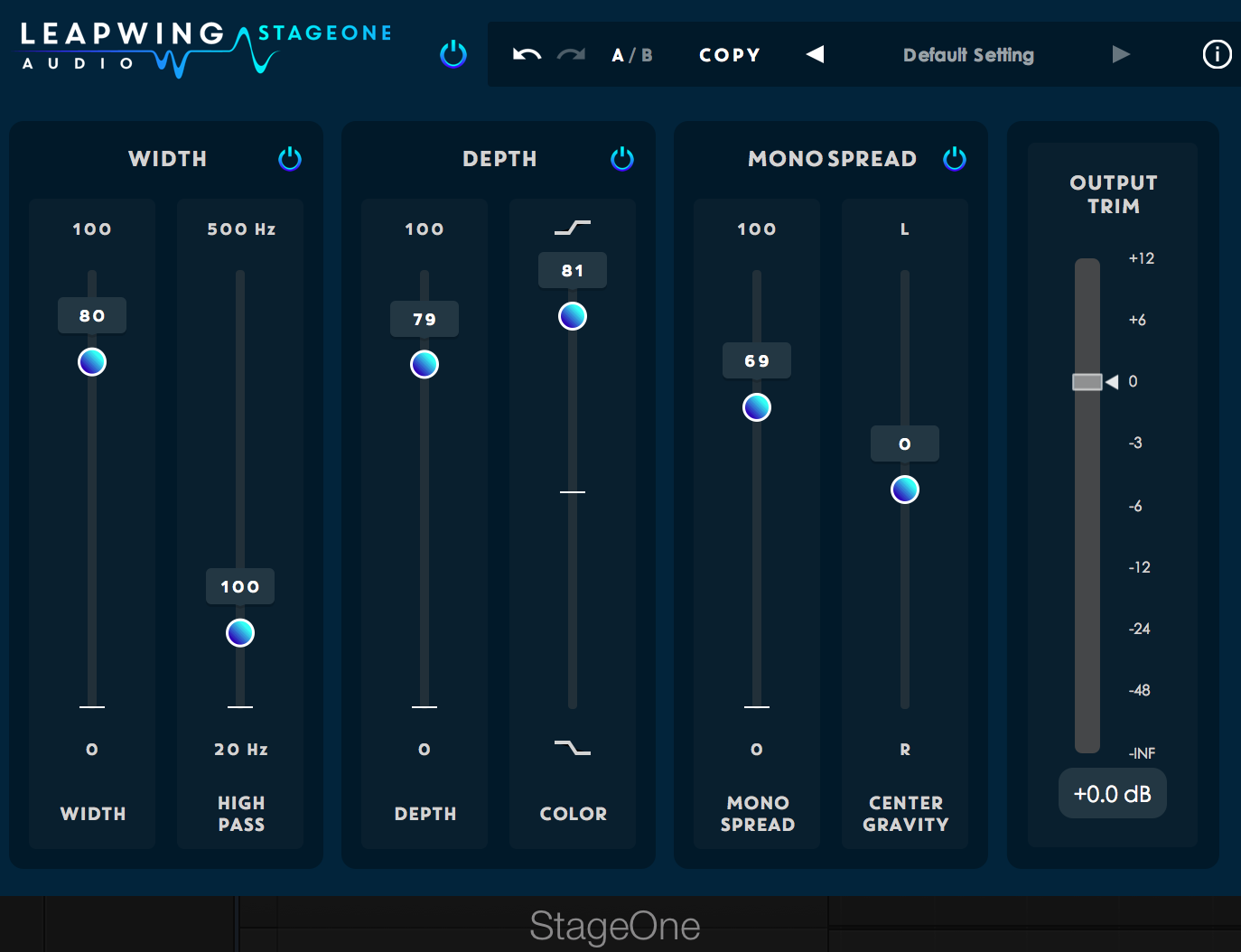

Here’s the tune, driving the width and depth:

We’re using 40% width, but it doesn’t feel much wider. The Mono parameter, as established, adds a weird quality to the vocal.

So let’s introduce CenterOne before StageOne, bringing the L and R channels up by 0.6 dB:

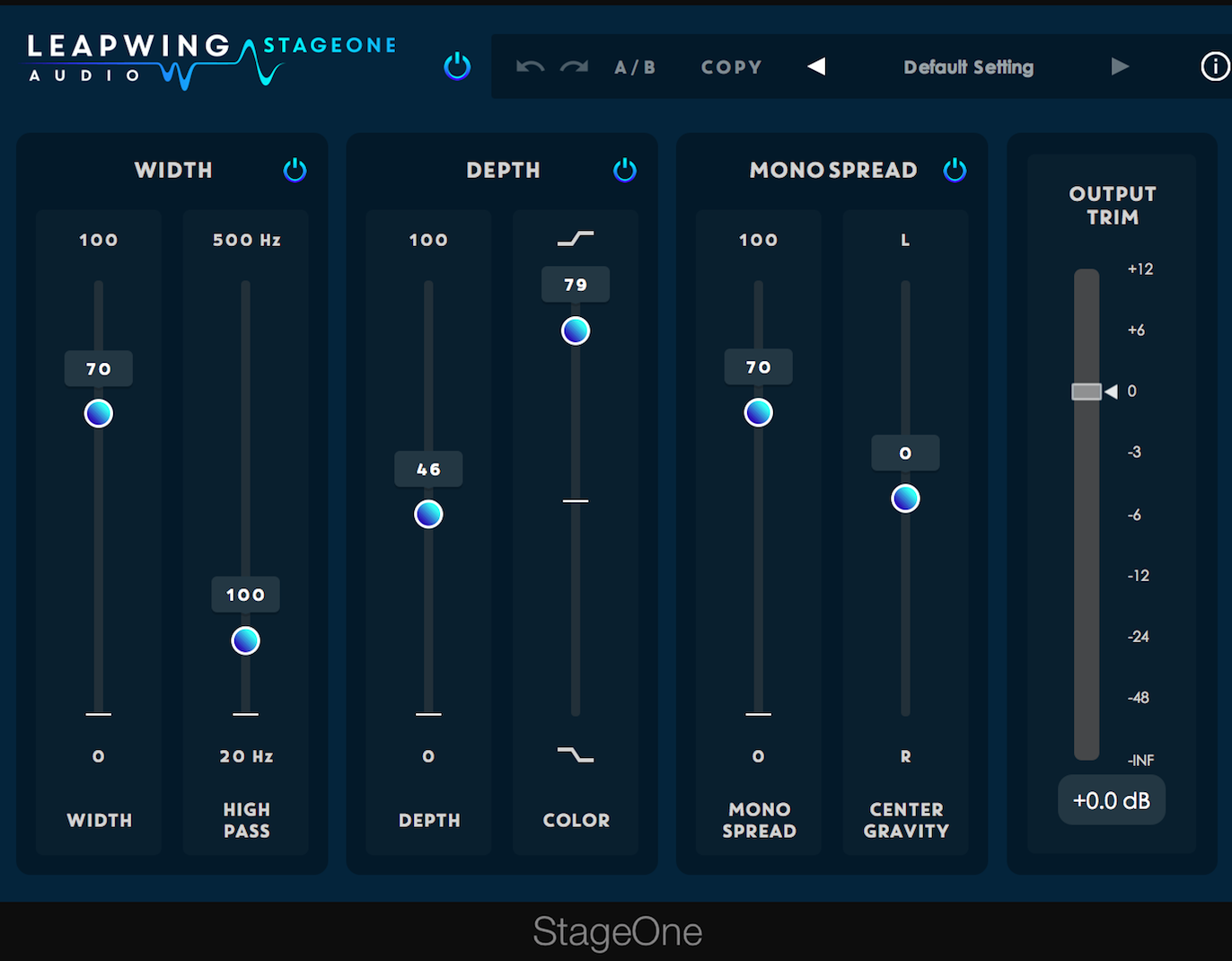

Now we’re getting somewhere. Let’s look at the settings employed:

We’re using more Depth than we did on the previous mix, but these acoustic instruments seem forgiving of the added reflections. The fact that the mix is already wet doesn’t hurt; it allows the reflections to complement the vibe of the tune.

We’re using more Depth than we did on the previous mix, but these acoustic instruments seem forgiving of the added reflections. The fact that the mix is already wet doesn’t hurt; it allows the reflections to complement the vibe of the tune.

But consider the lead vocals now: they could use some rebalancing, as they’re a bit loud. So let’s see what a second instance of CenterOne can do for us, placed after StageOne.

First, we’ll band-pass the center channel to target the vocals and bring them down by -0.4 dB. Then we’ll bring the Center Prominence down -1.1 dB. Finally, we’ll adjust the level trim for level matching with the original.

Next up, individual instruments.

When you’re presented with something like a power trio, it’s tough to come up with inventive ways to stereoize the guitar. It’s a challenge—if guitars, bass, and vocals are going up the middle, it can make for a boring mix!

We do have a few tricks up our sleeves. We can copy and delay one side, but that leads to strange issues in mono. We can edit the track so that a later verse doubles an earlier verse (hard panned left and right), but we’re out of luck if the track hasn’t been recorded to a click, or if the song doesn’t use a verse/chorus structure.

We can create stereo width with EQ—cutting some frequencies in the left and boosting others in the right—but this has a recognizable effect, and it can feel hollow over long periods of time.

With StageOne, we have a new tool—one that turns this:

Into this:

One of the beautiful things about StageOne is how it folds down into mono. Say we pushed that stereo guitar even wider:

Summed to mono, it still folds back into this:

Go with stereo hard-left/hard-right delay for a widened effect, and sure, it sounds nice:

But this is your mono fold-down:

Not exactly the most pleasant signal, is it? Since you cannot account for how your listener will enjoy your mix, it’s important to consider mono compatibility when implementing stereo effects. Leapwing did, and the results pay off.

Here’s a kooky trick I’m not using a lot in my mixes: parallel grit to bass tracks with CenterOne, followed by StageOne. Here’s the bass:

If you think you’re also hearing drums, you’re not crazy: this was recorded live, and there is some bleed. Anyway, let’s send it to a buss, and then exaggerate its upper midrange with CenterOne:

Next, some stereo trickery with StageOne:

Run this in parallel alongside the original bass track, and it sounds like this:

It probably sounds weird on its own, but within the whole track, this trick gives the bass a presence that cuts through the instruments. Observe this rough mix, pieced together only with Leapwing plugs for tone/compression, and Exponential Audio verbs on the drums.

To Be Critical

In this section, I’m supposed I tell you what I didn’t like about the plug-ins. But to be honest, I don’t have many gripes about them, and the critiques I have speak more to my own desires than the plug-ins’ architecture. “Wouldn’t it be great if these modules also did a million other things?!?” That’s about the gist of my complaints.

In terms of operation, I haven’t found a moment where either plug-in failed me because of an internal flaw, either with its sound or its GUI. None of my sessions have ever crashed the DAW because of StageOne or CenterOne.

What more could you ask for?

Summing it Up

Though we’ve only covered certain uses for these plug-ins (namely, mixing and mastering in music) for post-production and DJ remixing, CenterOne can certainly come in handy. You can use it to isolate elements for mashups or exotic remixes. If you work in film, you can utilize CenterOne to add elements into the center channel for theatrical releases.

But now, back to my original concern: how do these two plug-ins compare to the MBP?

They don’t, of course. The MBP is so much more than a widener. The hardware sports the enviable quality of making things sound better simply by running a mix through its circuitry.

Leapwing doesn’t build plug-ins the same way Slate or UAD does; they’re not going for overt box tone. That’s not to say these plug-ins are sonically invisible. There is a small signature, at least when compared to other digital processes. But I find it pleasurable.

To expect these plug-ins to replace a piece of gear like the MBP is preposterous. But to expect the MBP to replace tools like CenterOne and StageOne is equally so. I can’t rebalance an off-center guitar with the MBP; I can’t add front-to-back reflections with the MBP.

In the digital world, these plug-ins present a step forward in handling the stereo spectrum. Priced at $199 each, StageOne and CenterOne provide interesting ways to achieve great results. Indeed, in a strictly ITB world, I’d probably reach for them first when attempting any buss-related trickery.

– As a composer of musicals, Nick Messitte has seen his work enjoy the stages of Edinburgh’s Fringe Festival and New York’s Musical Theater Festival to critical acclaim; as a guitarist, he’s played with internationally renowned musicians, including Sam Rivers, Hawksley Workman, Gary Thomas, Devin Grey and Daniel Levine. Nick is also a sound designer of theater and film (with credits such as the award winning I Hate Myself and Sumi) and a producer/engineer of records (credits include Bullet Proof Stocking’s critically acclaimed EP Down To The Top, which Nick mixed, mastered, and supplied with additional instrumentation). Lastly, he is a writer/cultural critic, whose musings can be seen regularly at Forbes.com.

Please note: When you buy products through links on this page, we may earn an affiliate commission.