Precision Latin Mixes and Smart Business: Sonic Gems from JC Losada

“A truly hybrid and intricate system.” Producer/mixer Juan Cristóbal (JC) Losada is discussing his SSL + Pro Tools signal path here, but he could also be referring to something else entirely: his dynamic approach to the music business.

Born in Venezuela, then a certified GRAMMY and Latin GRAMMY-winning hitmaker in Miami, Losada now calls New York City home. But the roots of his success lay not in any one locale but in his ability to adapt to changing industry landscapes, rolling with changes while carving out his own unique path in the process.

In NYC, one obvious differentiator is his studio. His sonically accurate setup, centered around an SSL AWS 948 Delta, is situated within the midtown offices of peermusic, a prolific publisher with the sage wisdom to partner alongside Losada and explore fresh creative convergences between music, audio and publishing — some of which have already resulted in epic albums and GRAMMY Awards.

For this meticulous multitasker, however, it’s all about artistry: in producing, mixing, performing and educating. What follows is a big interview where every concept is essential, so let’s lose the ado — and dive into everything JC Losada has to offer.

First off, tell me about where we are. Where is this studio? This is kind of an unusual set up and business arrangement that you’ve got.

When I made the decision to move up to New York City, I got an amazing opportunity. Mary Megan Peer, who is the deputy CEO of peermusic, offered me the option to expand on our ten year partnership, and relocate it from Miami to NYC. This is an office that takes care of royalties and legal, and only the classical music department is here. So part of the idea was to put together a creative hub out of New York, which as we all know, it’s one of the biggest creative epicenters in the world.

Now we are developing writers out of the New York office, and also taking care of the writers that come from other countries. Recently I worked with a writer that came from Australia, Juliana Barilaro, who is signed out of the peermusic office in Sydney. Also, I had the opportunity to work with Mr. David Foster — who came from L.A. to collaborate on a new Broadway Musical that he’s working on.

Part of the idea is for me to take care of not only the New York-based writers and producers, but also internationally. These are writers that come from other peermusic offices, as well as the projects that I get from my company as an independent producer.

What are the benefits to you and your career, as a producer and mixer, of having an arrangement like this with a publisher?

It’s not a usual arrangement in the sense that publishers generally are not in the business of developing masters. And I’m in the business of developing masters as a producer and as a mixing and recording engineer. So both parties get real benefits.

Having this kind of partnership obviously generates extra traffic for my company. For example, the songs for that Jon Secada album are part of the peermusic catalog. So the idea of re-recording some of these songs is reviving the catalog, right? It’s a catalog that has many many years, so they use my services for me to develop these new masters that are going to revamp their catalog. So I won a GRAMMY at the same time that I was providing my services for peermusic on this beautiful album.

Congratulations!

So it’s a win-win situation. They have an in-house studio and engineer, and I have an in-house publisher that brings me traffic and new projects and new clients. Since I’m also a songwriter, when someone comes in town and they are looking for collaborations with a writer, I’m the go-to guy not only because of my credentials and expertise, but also because I’m in-house.

From there, the relationship with this songwriter might go beyond that, and then we might start working together on new songs or productions.

I wonder why more publishers aren’t doing this arrangement.

Remember that peermusic is an old company, so they have a catalog that ranges from “Georgia on My Mind” to “Mambo No. 5” to “Umbrella” by Rihanna. So there’s such a variety of songs and styles in their catalog that they are one of the first companies that realized, “Okay, we need to revamp this catalog. We need to keep this catalog alive.” One of the ways to do that is developing new recordings of old songs.

Also remember that songs eventually become public domain, and the company is 90 years old — so some of these songs that are in the catalog are about to become public domain. So how do you get around that situation? You develop new recordings or new compositions based on the old catalog, so you can renew this copyright and keep this copyright alive, not only creatively, but also financially. So I think some of the newer publishing companies, at some point, are going to start doing the same as their catalog starts aging.

Office Space to SSL Studio

Let’s talk about the studio itself: There are things you can do here, things you can’t. I imagine you’re not going to set up a drum set in here, right?

Well originally this is an office space, maybe like 14’ x 13’, with about a 10-foot ceiling. So originally this is just an office space. When I came in, I had to kind of like work on it a little bit. The idea was to set up a creative suite for these writers to come in, and for me also to take care of my independent projects. So I brought in an SSL AWS 948 Delta. In my studio in Miami, I used to have an SSL 4000. When the moment came for me to move up to New York, I had to make a decision which felt sad at the moment to get rid of my vintage board. I loved that board. It’s a beautiful sound. I think it’s one of the consoles with the most number one hits in history.

But also as times and music styles have evolved, blended and merged into each other, I felt that the sound of the 4000 was getting me stuck a little bit in that crunchy, greedy sound from the SSL 4000. But now that I’m working on the AWS 948, I have more options. It’s like having a bigger palette for you to choose different colors. The fact that you can split the EQ, you can turn half of it into an E or a G EQ. You could use the outer bands on an E configuration and the inner bands in a G configuration, so the same EQ can work as two types of EQ.

Also this being a small space, when I was getting ready to move to New York, I was thinking “Okay, how am I gonna move the 4000 up to New York?” You know? To set it up there is going to take a lot of real estate. You need a big room. You need to set up air conditioning. You need an extra room to set up the power supply. So I decided to make the move to a smaller footprint.

This is still a 48-channel console in a 24-fader frame. So you can set up your channels as mono channels or stereo channels, or just split the board and use half of it in mono and the other half in stereo, which is as I have it set up right now. The first 16 channels are mono channels. So I do my drums, bass, lead vocal, double vocal. Then, the last bucket of eight faders, I have them all configured in stereo. Why? Because modern mixing uses a lot of stem mixing. You know, you have all your synthesizers come out in stereo channels. Or, for example, I pre-mix my background vocals inside of Pro Tools.

How would you approach that?

Let’s say I have 24 channels of background vocals, those are pre-mixed inside of Pro Tools, and then they come out in one stereo channel on the console. So one of the cool things is that I can split the board, and half of the board could be controlling Pro Tools, and the other half of the board could be analog faders. So instead of me having to flip pages and faders, you can have everything on one layer.

The flexibility that I’m finding in this console is definitely something that is more in tune with modern production and current workflow. As you have two or three different sessions in one day, you have to be flipping between one project to the other one, so this console definitely allows me to do that in a seamless way.

What else is going on in this room, besides the console?

As I was saying before, it’s not intended to be a recording studio per se, as we don’t have an isolation booth at this point. It’s more of a creative space focused on mixing and production. We can do all the programming for the song, we can record vocals, we can record guitars. If we have to do a big drum recording or that sort of stuff, then we would go to a different studio. But other than that, the whole production could be done here from the click to the final product.

I’m also using small, old model Genelec speakers which are very transparent, and I’ve been a Genelec user for many, many years. I have also the ADAM A77X with a JBL sub. Since these are ribbon twitter, they have a little bit of a peak somewhere in the high range, but once you tune your ear to it, then you understand that some of the stuff might have a little bit of a peak, maybe around 5 or 6 kHz. But then you tune your ear and tune your room according to that, and then you learn how to compensate.

I always say that there is no perfect setup. There is no perfect speaker or perfect room. It’s just a matter of tuning our ear to the environment that we’re working on. You could bring $10,000 speakers or $20,000 speakers, and it’s not about the speaker, it’s about the ear that is listening to those speakers. Once you tune and you calibrate your brain with those curves, with those peaks or those notches, then you can communicate with your system better and have a more transparent result that is going to be bulletproof.

Why do you like working on this hybrid analog/digital system?

The console is totally analog even though it’s a hybrid console. As I was saying before, I spread out my channels from Pro Tools, and everything goes through EQs, and I use the summing of the board. I use of course, all my SLL EQs, which are my favorite, and the master section of course. You have the master bus compressor, and your master fader.

So what I do is I play back out of Pro Tools, spread out my Pro Tools channels on the board, EQ on the board, some compression on the board. Then for my reverbs and delays, what I do is those channels that are coming in the board I send out of my auxiliary sends. I send back into my interface, and then I use Pro Tools also as my effects rack.

One other thing is that I’m using Universal Audio plugins. So I have my Lexicon, I have my Manley, all of the goodies. I also have the SSL EQs by Universal Audio. But when it comes to reverb, definitely the Lexicon 224 is my first option. I used to have a 480 Lexicon in my studio in Miami, so I’ve been a Lexicon fan all my life.

Going back to how the setup works, my channels come out of Pro Tools into my SSL, then out of my auxiliary sends. These auxiliary sends are connected to the interface, then out of the auxiliary sends go back into Pro Tools, excite the reverb that I have in here, and out of the reverb I open an auxiliary channel in Pro Tools. Right? I open up my reverb over there, and out of the reverb in Pro Tools, come back into the interface, and then it shows up into the effects return of the board.

So it’s like if I had an outboard reverb unit, but instead of being an outboard, it’s in Pro Tools. But other than that, it’s being sent from the analog path, and it returns into the analog path of the board on the effects return.

So that’s one of the things that makes the system really hybrid, that I’m using Pro Tools also as an effects rack, but it’s being sent and received out of the analog path.

I see. So where does the mix bus come in?

The signal comes out, then comes back in, then comes back in the effects return, and then the mix gets printed back into Pro Tools. So it’s like a four-, five-way in and out. Then I use the mix bus to actually do the mix, and then the external source input of the SSL to monitor the mix.

Whatever’s getting printed into Pro Tools, the mix comes back here on the external source, which allows me to monitor the mmix without the signal going through additional paths on the board.

If I want to listen the actual mix coming out of the board, I listen to the mix bus. And if I want to hear what is being actually printed in Pro Tools that returns in one and two, of course I set up these two channels at zero dBs, and then pan them out, so this is an exact reflection of what is being printed.

Then also as I’m printing in Pro Tools, I assign the Manley EQ inside of an auxiliary bus before printing the audio. I usually use the Massive Passive Manley EQ, and I usually also use the Vari Mu Manley compressor. So as my mix comes out of the master bus from the SSL, goes into an auxiliary channel into Pro Tools, I do some EQ. Kind of like a little pre-mastering or just color the mix a little bit. You know, maybe sometimes compensate a little bit for the high end. Maybe I add a little punch on the low end, and a bit of compression.

So after the master bus compressor, come back into Pro Tools, Manley, and then after the Manley, I put the Vari Mu. And then out of that auxiliary bus, then I print into an audio channel. Then I print my mix in Pro Tools and then I monitor that mix through the external source of the SSL. It’s like a truly hybrid and intricate system.

The integration between Pro Tools and this SSL console is off the charts. How you can control Pro Tools, how you can run your automation now with Delta automation, which is a Pro Tools plugin now you can control your SSL analog automation from a Pro Tools channel, as if it was any automation that you’re doing inside of Pro Tools, but it affects your analog fader, which is wonderful.

So there’s no outboard whatsoever now.

I owned the 4000 console for maybe almost 15 years I had that console. But in Florida, the electricity is very unstable. I used to have Manleys, 1176’s, LA-2A’s, API EQ’s, Summit DCL 200. Those are beautiful toys. I love my toys, don’t get me wrong. Please guys, if you’re listening or reading out there, I’m not deserting you! I’m still an outboard freak.

If your mix is sounding beautiful, and you want to go to sleep and listen to it the next day. Then you come in next the day, and for some reason it’s not sounding the same. It can be the electricity. But instead of being 110 [volts] it’s 115 that day, so your tubes are getting a little warmer.

And your LA-2A is not responding the same way, and then you have to tap it a little bit or let it warm up. All of these little moving parts that might change the sound of your mix from one day to the other, or maybe in a matter of hours. And having to deal with the recall situation plus all the outboard gear recall, it really was getting out of hand.

That’s one of the reasons why I’ve decided to switch it up. I’m an outboard gear lover and collector, but when it comes to work, I needed to change the workflow. So right now, the only outboard gear that I have is my Antelope Orion 32 interface, and I have the Universal Audio Apollo Twin interface, but I only use it for DSP. I’m about to buy a Satellite also so I can increase the DSP on that, but shout out to Universal Audio. They’re doing a great, great job with their plugins. The Lexicon, the Manleys, the Neve, the SSL, and all the Pultecs.

A Multicultural Mixer

Let’s turn our attention to how you mix, and what kind of mixer you are. How would you describe your lane as a mixer right now? Where are you an expert?

That is a hard question, because I think one of the things that sets me apart is diversity. I was in Miami for 16, 17 years, and I’m originally from Venezuela. At the same time that I grew up listening to Latin music, I also was playing drums in my rock band in Venezuela, and I’m a big Beatles fan and classic rock fan, but at the same time I’m a salsa and bolero fan.

So I think one of the things that set me apart is being able to work in many different genres. Not because I intended it that way, but just because I grew up listening to all kinds of music. And as you know, Miami’s very diverse. Of course, the diversity in Miami is mainly Latin, so I have a lot of that influence in my work. But also, I’m a drummer and I used to have my rock funk band in Venezuela, and I grew up listening to many different genres, but radically different, from hardcore salsa, to Beatles, to Queen. So I think one of the things definitely that sets me apart is the diversity, because of my musical background.

I used to play the violin when I was a kid, and then I used to play also the cuatro, which means “four,” which is a folkloric instrument from Venezuela. Then as a teenager I started playing percussion and drums, and I went to Cuba a few times to learn some Latin percussion. So for example, when I was engineering Santana’s album, I ended up also playing percussion in one of the songs.

And that’s one thing that I don’t think all engineers can say. Before being an engineer, I’m a musician, and being a musician gives you a wider background when it comes to approaching a mix, because you’ve been sitting on the musician’s seat before you sit behind the board. So you kind of understand both sides of the glass, let’s say.

No matter what the genre, how would you say a mix takes shape for you? What’s your starting point, and then how do you start to work it so it begins to evolve?

I always say that drums and bass, or percussion are like the trunk of the tree, the spine. Then, the branches of the tree are the guitars, the keyboards, the background vocals. And then at the top of that tree up there are the vocals.

If it’s pop music, kick drum is the first thing that comes into mind. And I always put the kick drum on fader number one. So drums and percussion, then bass. Once I make sure that my drums — I’m saying drums if we’re talking rock or pop — I would say percussion if we’re talking salsa and Caribbean music.

So once I make sure that that spine is straight and strong and able to support the other branches, then I move on to the bass, which is like the root of that trunk, and then I start working on the branches. Usually I start, depending on the genre, with piano or guitars. A pianist that is also a mixer might be like, “What do you mean you start with the drums? You have to start with the piano.” Some people might even get offended if I say that guitars and piano are the branches of the tree. But again, there’s no rules. There’s no written rules. This is just a matter of preference. That’s also what I always tell my students: “I’m only giving you tools for you to develop your own technique.”

You mentioned your collaboration on various projects with Erika Ender, the co-writer of “Despacito.” A lot of people who are reading this now may be primarily hip hop, rock or pop mixers, but with the success of that song and others like it now, they know that their first Latin mix might come in the door tomorrow. If they’ve never had a song like that come to them, is there a different mindset that you need for that? What makes it a little different to be mixing for the Latin genre?

Well you know, one of the things with us Latinos is we are very romantic and passionate, so for us, vocals are really important. We want to make sure that those lyrics come across. You’re trying to, like “Despacito” for example, co-written by my good friend Erika Ender. Even though it’s a very sexy song, despacito means “slow,” like “let’s take it slow.” It’s actually kind of empowering women. So for us, lyrics are very important.

If you go back to all classic Latin songs, you’re always going to notice that the vocals are really loud, we could say. But it’s part of our culture. Spanish language is the romantic language, and it’s very rich. And of course the rhythm: Latin music is all about rhythm. It’s about shake it, shake that booty, go to the dance floor, make sure you can dance! Maybe that’s also why I start with the rhythm when I’m mixing, because for me, and for us Latinos in general, the rhythm is what’s going to make the difference. The rhythm is what’s going to get people dancing, the rhythm is what gets your song played on the radio.

Even if it’s a slow song. You know, we also do lots of ballads and romantic songs, so you always make sure those drums bam, boom, boom boom boom! You know, they’re beefy and heavy, even when it comes to ballads.

So if you’re mixing a salsa track, you would think that the congas are the equivalent to the drum set. When it comes to salsa it’s all about the congas. And then you have the timbales, doing the shells, and the maracas would be the hi-hat. So if you’re mixing a salsa track for an artist like Marc Anthony or something like that, then you would think that you want to make sure the congas, the timbale, the maracas and the güiro are building the equivalent of a drum set.

But these are just general appreciations. When you have a song like going back to the case study of “Despacito,” I think the lines have been blurred when it comes to the genre and the mixing techniques. Because a song that starts being a Latin song ends up being a global phenomenon, regardless of how it was mixed. Regardless of what the lyrics say.

When I grew up in Venezuela, as I was telling you before, I grew up listening to the Beatles, to Queen, to The Clash, to The Cure, and I didn’t understand most of the lyrics. It was all about how the music gets you and how it surrounds you with the rhythm, with the melodies, with the textures or with the vibe. You know? So I think the world now is ready to sing in Spanish, even if they don’t know what it’s saying. It’s about the overall content in the song. Like the rhythm, the melody, the Spanish rap, and then you have Justin Bieber singing in English, but then you have Daddy Yankee and Luis Fonsi singing in Spanish. It’s like it doesn’t matter anymore. It’s like it’s a big world out there, and also thanks to companies like Spotify, the globalization of music now is a reality.

So I think there’s a big cultural and social element that also comes into play when we’re talking about mixing, production and recording. It’s not only about the music, it’s also about the society and the multicultural world that we live in right now.

A GRAMMY-Winning Approach to Jon Secada

The mix on the song “Como Fué” for Jon Secada’s GRAMMY-winning 2017 album To Beny Moré With Love that you just played me, that’s a different thing than a “Despacito,” for example. That’s a very luxurious mix, requiring next-level skills to pull off, if you ask me. How did you approach mixing that song?

Well that was recorded in Puerto Rico, and it’s a big band. It’s a full big band and that was all recorded live. I think it was four trumpets, four saxes, four trombones, piano and full percussion set, and of course voclas. It’s a Latin jazz big band trying to emulate how the big bands were in the ‘50’s and ‘40’s, because the song was originally written in that era. So again, go to my congas, go to my bongos, go to my timbales, and make sure the rhythm base is strong.

Of course, the challenge with this kind of recording is that everything was recorded live in the same room, so you have the instruments bleeding through microphones that are not supposed to come through it, so you have to sometimes over-EQ or compensate for some frequencies in order to mask the bleeding, or play a lot with mutes. And the problem with the mutes is that when you mute something, the overall ambience of the mix changes, because that noise that is in the background is part of the overall ambience of the mix.

JC Losada played an important role in the GRAMMY win for Jon Secada’s 2017 album “To Beny Moré With Love.”

We could say the genre of this song is bolero jazz, so that’s your drum set right there. You have your maracas doing the hi-hat, and you have your timbales doing the cáscara. So it’s like the same approach that we were talking about earlier, make sure the spine is strong. And then of course you have all of these horns happening, piano, and of course the bass. But always, I bring first all of my percussion. Make sure the percussion is tight. And then once you have that well put together, then you start putting all the sprinkles around.

And this also had the challenge of we’re trying to reproduce the sound of an era, you know? So even though you want to make sure it’s very clean and pristine, you also want to leave some space for that roomy sound, and a little bit of that dirt that a live recording brings, because you’re trying to emulate some of that sound from 50, 60 years ago. Part of the challenge was to let some of that noise, which I would call ambience instead of noise, to be turned into a tool that is part of the overall concept of the mix.

Another challenge is that we did two versions of that song. We did one version that Jon Secada sang the whole song, and we also did a version with the original singer of the song. So we had to take the original two-track recording from RCA, and the big challenge, of course, was to clean up that two-track in order to extract the vocal as much as we could and isolate the vocal from the rest of the big band. Then we did a virtual duet with Jon Secada and the original singer of the song which is Benny Moré. It’s kind of like what Nat King Cole did with “Unforgettable” and his daughter, Natalie Cole.

(embed code for Come Fue on YT)

Artistry and Education

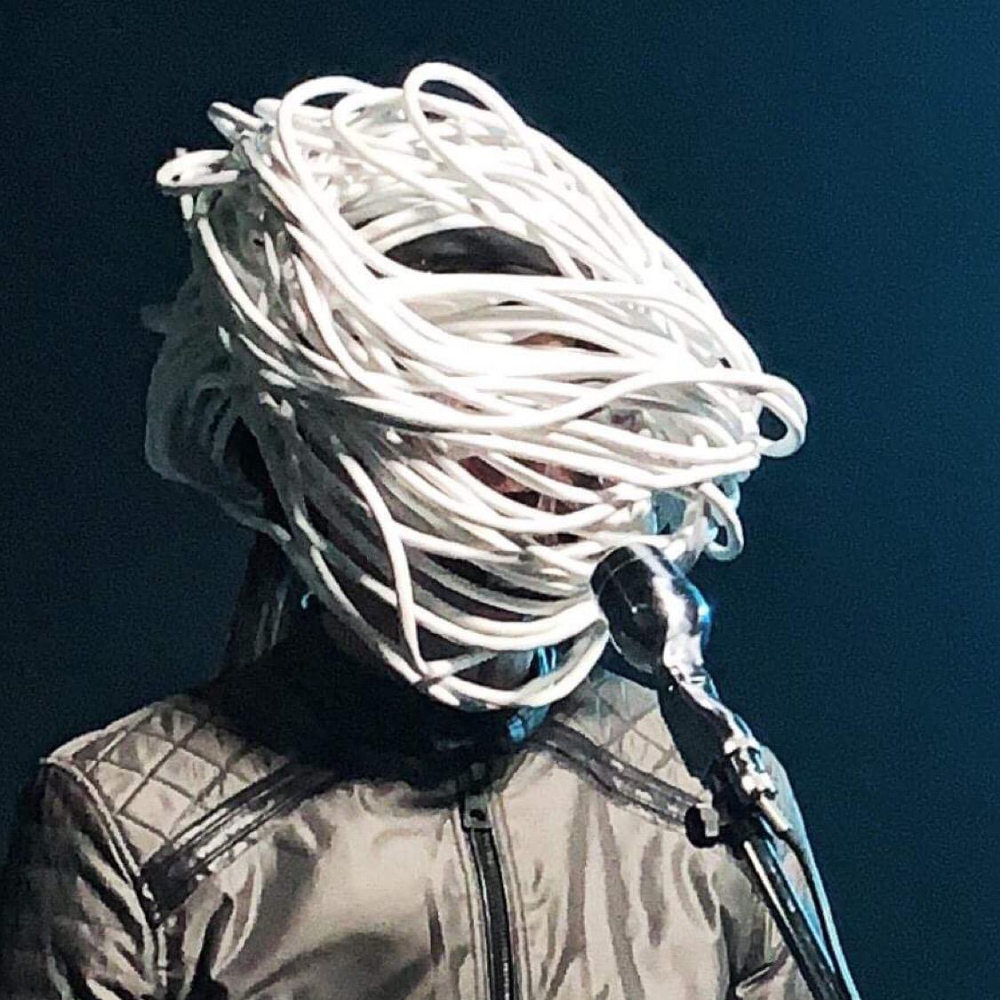

Another way you’re making waves on the musical front is by producing Cable Head, a “music performer and activist” on Sonic Projects/Sony Music US Latin that’s gaining good traction. Why do you refer to Cable Head as a modern superhero?

Imagine if you had the opportunity to travel 200 years in the future and see the devastation that mankind had brought to our planet and society. If you could come back to our time, wouldn’t you tell everybody what you saw? Wouldn’t you bring this message to your fellow humans about bullying, war, the environment, teenage suicide, all of these issues.

As a producer, I wanted to get behind something that went beyond music itself. When you have an artist that brings something different to the table, it turns heads: With all of the attention that Cable Head is getting, I’m experiencing that first hand. Cable Head had it’s live debut at the BMI SHowcase during the LAMC, standing out from other performers with its impactful message and powerful image, that’s what I’m talking about.

The debut single, “Cierro Los Ojos” is extremely catchy.

Thank you! The songs are great, but it’s more about the message. The superpower that Cable Head has is that he can change consciousness through sound & technology. A key element on this project are the visuals, the video produced by “El Living” , has had an impressive organic growth on Youtube. People are latching on to the message and the image, which is amazing!

Another part of your move to New York has also involved you being a professor at NYU as well, right?

Being at NYU is definitely a very exciting side of my career. I’ve always been really excited about sharing the knowledge with the young generation. All musicians, producers and engineers complain about the state of music industry and how things sometimes are hard or unfair.

So I say the only way to make a change is from within, and that’s educating the new generation. We can give them a few tools so they can be aware of some of the things that we went through, and they can use some of our experience to shape their own path, and avoid making some of the mistakes or some of the situations that we’ve been through.

I had been a guest lecturer at NYU in Steinhardt [Department of Art and Art Professions] for the last two or three years. At some point after getting great feedback from the students, they offered me a position as a professor in the music tech program and made me a producer in residence for the music business program.

So right now I’m teaching two classes at NYU. One of the classes I teach is Fundamentals of Music Technology, and then the other one is called Village Records, which is a label that NYU created and is part of the music business program.

One twist that I give to my music tech class is that I want to make sure that each of these students comes from a different background, because as you know, the student population at NYU is so diverse. I have students from China, Singapore, South America, Puerto Rico, from Canada, Australia. I want to make sure, following our previous conversation about the globalization of music, that each of these group members comes from a different background. Not only that they have different skillsets, but also that they come from different cultural backgrounds, because to me that’s the future of music.

So where are we going to find the next “Despacito?” It might be in Asia, the Middle East, India. So at the same time that I’m teaching the students how to use the basic concepts of music technology and how to apply those to music production, I’m teaching them how to collaborate, because this is all about collaboration.

And I’m also teaching them about cultural integration through music. Because music is all about innovation. What happens if I blend tablas from India with a violin from China or with a balalaika from Russia with some congas from Puerto Rico? That’s where the next big thing might be.

Wow. For my final question I want to ask: How would you advise an emerging mixer or producer who’s reading this on how they could build up their own career?

The first thing I always tell aspiring producers and engineers is “Use your ears.” This is sound engineering. Forget about those plugins that have all of these lights and meters and flashiness and little meters and LEDs and all that. Don’t look at those. Don’t get distracted by those. Use your ears.

Those lights and flashes are there to give you a little bit of support, a little bit of guidance, but the problem now is that when you’re mixing in Pro Tools, when you’re mixing in the box, you’re looking at a screen at all times. So instead of focusing your energy in your ears, you’re splitting your energy. Half of it goes to the screen through your eyes, and the other half stays in your ears.

The problem with that is that when your song is ready and you send it to a listener, the listener is just listening. They close their eyes, and they listen to the music, so they’re only getting half of your energy, because the other half of your energy you wasted looking at the lights. But when you send the mix out for digital distribution, or you send it to the GRAMMY committees, they’re not going to be looking at the meters. They don’t have all the flashiness in front of them.

Music comes through the ears, and you’re supposed to convey all of these emotions and all of this message just through the ears. Trust and develop your ears. Make sure when you’re listening to your mix, your ears are so in tune with your brain that you could see the lights only by listening.

— David Weiss

Please note: When you buy products through links on this page, we may earn an affiliate commission.