Research & Development: Designing Rockruepel’s sidechain.one Compressor

How does a new kind of compressor get designed and built? Get inside the creation of the innovative sidechain.one compressor from Rockruepel.

The versatile Rockruepel sidechain.one is a mono VCA compressor which features sidechain filters for advanced control options.

“Building the gear is not the hardest part,” says Stefan Heger. As the partner of Rockruepel, a boutique analog audio manufacturer based in Düsseldorf , Germany, Heger has a wealth of experience when it comes to introducing new gear to producers, mixers, mastering engineers, and studios.

One by one, Rockruepel has brought several intriguing offerings to the audio crowd. They include the comp.two high-end compressor and limit.one analog dynamic limiter, each of which made a name for themselves with discerning audio engineers. Designed with a simultaneous mindset of providing highly useful studio tools built to extremely high audio quality specs, Rockruepel reflects Heger’s direction, honed by his decades-long career as a mastering engineer.

In this “Research & Development,” you’ll learn what goes into creating a new piece of analog gear. Focusing on the innovative Rockruepel sidechain.one analog sidechain compressor, we’ll uncover it’s unique journey into existence: What’s the signal path from creative spark to napkin sketches, on to prototypes and finally the finished product?

The challenges can be intense. Heger and his partner Oliver Gregor — the technical brains behind rockruepel — pulled back the curtains on how the sidechain.one was designed and built. As you’ll see, the road to getting small-batch audio gear into people’s hands takes inspiration, ingenuity, patience, and persistence.

Thinking of making your own analog audio gear concept a reality? Or have you ever just been curious how new analog studio equipment is created? It’s all here, in the story of the sidechain.one.

Stefan, why do you believe that analog gear is more important than ever for mixers and mastering engineers to have in their toolkit?

Stefan: I don’t think it’s more than ever, but it’s the logical step when you work, whether it’s mixing or mastering. Because ultimately, we end up listening via the speakers and we’re listening to analog music. The control and enhancement over music has a really important role to play in the analog domain.

Eventually you are dialing into what you’re hearing, which is analog music. Our ears are analog and the dials and everything is analog. That’s why I think that everybody needs to explore it to find out if that’s their way of working.

I’m in this position where, over a long period of time, I was able to collect very good gear and had the chance to play with a lot of analog gear. The more I do what I do, which is mastering, the more I feel like I’d like to be in control in a physical way with it. I couldn’t say that a plugin is not good, but what I could say is that I can’t use a plugin with my eyes closed in the same way that I can do it with a knob, a structure, something that’s in front of me where I can put my hands on it.

The sidechain.one has a very unusual concept in controls. What is your “elevator pitch” on the sidechain.one? What makes it different?

Stefan: The sidechain.one was invented with the idea of, “What tool do I not have accessible to me in the analog domain?” That’s where the inspiration came from, and that’s where Luca Pretolesi comes into the picture. He would do workshops showing how he would use the Dangerous Music BAX EQ to control the Dangerous compressor by dialing it in. Both units, roughly add them together, and you’re at about $6,000 for the two!

The original “napkin drawing” of the sidechain.one rendered in Adobe (note faders have not yet been incorporated in the design)

Besides the money, it also was a big effort for something kind of subtle that he showed in his workshop. That gave me an idea: “Why not build a tool that takes away very little rackspace but does something with full flexibility, with the ability to select your sidechain frequency no matter where it is?”

Some of the frequencies are more obvious to you as a user, some are less. But I didn’t want to draw the line — and I’m saying this because a sidechain frequency usually is in the lower range, like a low cut at 50, 80, 100 Hz. That’s sort of what you see on every compressor, but I didn’t want to stop there. I wanted to say, “No, let’s go all the way.”

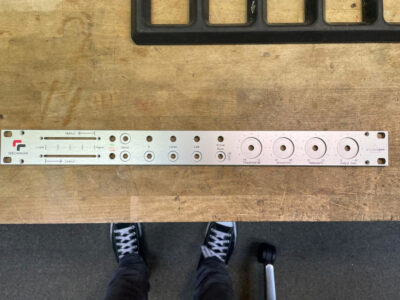

That’s why you have these faders that are unusual. We’ve looked into trying to do this with dials, but a fader was just a more obvious thing to do at that level.

A compressor should be very neutral-sounding, but then again with a very wide range of attack and release. Controlling the kick drum in MS (mid-side) is Luca’s main feature. I thought, “Okay, that’s great, but that limits it to just one thing really.” That’s why we have a very slow and a very fast release and a very slow and a very fast attack just to dial in to whatever you desire to do.

Can you explain exactly what the faders control?

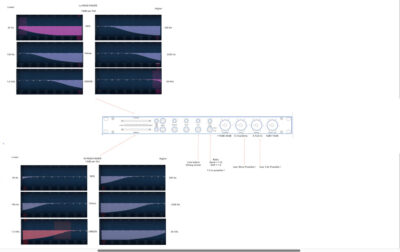

There’s a top and a bottom fader. In the default setting you have a frequency range from 20 Hz to 20 kHz. The fader on the top controls the high frequencies, and the bottom fader controls the low frequencies.

By pushing them together, you basically have a low cut on one side and a high cut on the other, about 12 dB octave. You squeeze them together so that you end up with a band pass — a wide one and a narrow one. You can choose how skinny/thin you’d like to do your band pass. And besides that, you can then move the band pass.

But you cannot only control the width, you can also control where it is at exactly, and in order to have a more finer way to choose it, there is a dip switch next to the faders. We call them “high,” “mid,” and “low.” That takes the range of the fader into the high frequency range, mid frequency range or low frequency range. They’re in the manual: It’s from about 0-200 Hz, 200 Hz-2 kHz, and then from 2 kHz all the way up.

Audio Inspiration

Tell me more about how this presentation by Luca inspired this? Did you find that you had that idea right away after seeing that presentation? Or was this something that kind of had to marinate?

Stefan: I’ve seen him (do his presentation) more than once, so maybe that helped. Luca does a lot more mixing than I do, but I use the Dangerous compressor, I love it, and I also love the BAX EQ. But looking at my own studio, I was like, “I’m never going to use a BAX EQ for my sidechain.” For me, the idea of using such a brilliant loudness EQ, stereo EQ for something as basic as a sidechain trigger, I just said, “No, no, I can’t do it.”

From there I started feeling the need that one machine has to do that: It has to be one machine rather than an EQ that’s inserted into a compressor. That’s the drive behind the sidechain.one.

Oliver: If you use two different pieces of gear, it’s too complicated, not as much control. With the sidechain.one, you have the whole thing in one unit.

Oliver, what were your thoughts when Stefan explained to you what he wanted the design to be? What was your process as you began to bring the sidechain.one into existence?

Oliver: I just did what Stefan wanted, the shortest way, with not so many controls. For me, the design process is to go the shortest way. Fewer components make better sound. I just wanted to achieve a compressor with a simple sidechain EQ.

Again, the shortest path is the best: Just a state-of-the-art compressor with a state-of-the-art EQ fixed in a sidechain.

Fair enough! Stefan, what might you add to that about the design process and what you were looking to Oliver for?

Stefan: I’d like to add that his challenge was not just to do a sidechain compressor. The challenge was also where we were coming from as far as the brand. At Rockruepel, we like to look at something without the idea of finding a shortcut to make it cheaper. The sound needs to be great, it needs to be not altering in a way where you lose sonics.

My point to him was that I had a very high expectation that this compressor cannot muffle the sound. It cannot change the dynamic range. We’re very high end when it comes to how the gear is actually manipulating the sound. So that was my challenge for him: Not just, “It needs to have this functionality, but it also needs to just sound mastering-level quality. Please figure this out.”

Initiating Analog Design

Can you describe the major stages of the design process? What had to happen in order for the sidechain.one, to move from concept to prototype to finished product? I’m sure that there’s going to be some people reading this article that have their own ideas for analog gear. Let’s help demystify for them how a unit like this goes from the idea to being the finished product.

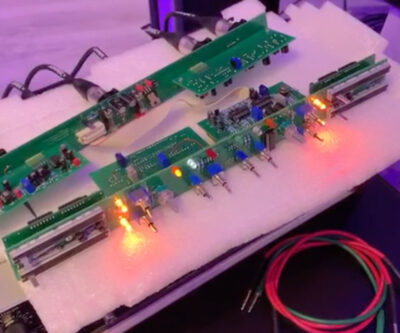

Oliver: First we start with an idea and a lot of sketches. Then I went into the circuits design phase, and I tried a lot of things. The first stage is I made just a bigger PCB (board) with more room on it to make some experiments. What would be the best way to get this task?

The first circuit went into the trash! Then I started the second board with a different circuit — this is what went into the sidechain.one.

Got it. And how long was that process for you?

Oliver: About a year. Because we had to send the prototype between Germany and the U.S. [where Luca Pretolesi is based].

Stefan: Luca was an early listener to the sidechain.one as well. So a year is actually quite good for what we did. But that introduced the cost of shipping the prototypes back and forth, the additional time of sitting down with people and saying, “I like this, I don’t like this…” That’s why it just takes time and money to do it right.

So Stefan, is it hard for you to tell Oliver, “You have to fix this and this and this.” I’m trying to imagine the collaboration process there. He’s driven an hour to get it down to you. He’s worked on it for weeks and it’s still not quite right.

Stefan: With every relationship, I think it’s about looking for the tone of how you say things. If there is a point where we disagree, then we manage to talk about it and not get upset. I think we both found a good way with each other.

Oliver: Yes. It could be about the sound or it could be that I have to look for good-looking screws or things like that.

Stefan: It comes down to that. Once the technical part is done, then the next really important part is to come. How does it look? Where is the logo going to go? Where is this going to go? How does this fit into the other products?

There’s lots and lots and lots to think about. And also, where do you want the company’s brand to go? What’s the overall vision? Because we’re doing this for such a long time that we’re not just saying, “Let’s build one box and then forget about it.” We want to be a company with a vision of where all this drives towards a long term commitment to our products and the support of the customer.

We’ve talked about the interaction between the two of you to get where you want, but then there’s a whole other level of complexity that had to be added by getting Luca’s feedback as well. When Luca made suggestions, would you have to go back to the drawing board?

Stefan: It was important that he’s on board with everything. He had the same right to veto. He’s part of the sidechain.one, so we took everything he had to say under consideration.

Getting to “Zero”

Of all those design stages, which proved the most complex to complete?

Oliver: I think it’s a stage of the serial number “zero.” When you first make a serial product, every component has to be right and available. Everything must fit together, and that’s the hardest part: To get final units where you can produce a series.

Stefan: That’s the part when, again, I have to put all faith into Oliver. I do have to let go of the final decisions and crunch the numbers. It’s significant, because we didn’t buy one unit per component. We had to scale up everything.

We’re a really small company, so anything in the 10’s of thousands of dollars is like, “OK, that’s a lot of money.” So the hardest thing is really to say, “OK, that’s it – here’s money.” Basically you’re buying something that you are hoping to sell.

You have no idea at this point. Nobody knows about it. You haven’t sold a single one yet. You have to give it a go before you can sell one unit, and that is a really tough thing. We went back and forth quite some time before Oliver said, “Let’s do it. Let’s make a hundred.”

And they’re built where?

Oliver: At my shop in Düsseldorf, Germany.

You’ve both designed several pieces of hardware. What were some of the lessons you learned from those past experiences that allowed you to save time and effort with the sidechain.one?

Stefan: I would have to say the lesson learned is that you can’t think it over enough. At a critical point, you need to involve a few more people for feedback. Because it’s the little things that if you were to leave out a small detail, it may decide the future of this product.

Small details are obvious to the first customer using it. In this case, the first units didn’t have a white line on top of the cap knob. It was hard to see, depending on the angle, where the knob is (pointing to). The sidechain.one offers wide ranges, so seeing where the knob is was more important than we thought, for example, on the comp.two or limit.one. Luckily we could change this and retrofit any units that were out there already. They’re all shipping with it. It seems like such a minor thing, but it is super important — we also offer to retrofit comp.two and limit.one.

Getting Gear Out Into the Wild

Now that the sidechain.one has hit the market, what are some surprising techniques and or applications that you’ve heard about from users?

Stefan: My network and my own work is so much into stereo and mastering, so obviously when I talk to a lot of people, that’s where we share common interests, and that was where I saw it the entire time. But we made a decision very early on by saying, “We’re not building a stereo unit, we’re building a mono unit.”

What we’re wanting to see is how people could use this with a mono channel. That means you are either recording or mixing and you can use it on any instrument, on any source you want to. For me the biggest excitement is to see if people start using it in mono — I’ve heard from at least one person who is successfully using it (that way) and loves it.

Also, because we chose such a wide range of attack and release, there are several studios that use it on a stereo bus on a beat or drums. They’re telling us that because you can control a frequency portion of the compressor to work at, that you can actually manipulate the groove of how something feels when it progresses. To me, that was like, “Wow!” That was not the intention. But it’s a groove maker, so you can actually take an existing groove or beat, and turn it to actually feel a little slower or like it’s a notch faster.

What type of audio engineer has already gravitated to the sidechain.one? And what type of user do you think will need some convincing?

Stefan: A mastering person is going to have an easy time because it’s a very clean, transparent-sounding unit, so they can focus on dynamic control. There’s no hurdle they need to overcome.

What I’m interested to see if we go in the direction of the mono use. Who will start using it on, let’s say, on an electric bass guitar, or on vocals? I’d like to see that, but that is just going to be a little bit of a harder thing. I think that will take a little longer.

Finally, what’s the Big Lesson that you learned from the process of creating the sidechain.one? Put another way, what advice would you give to someone thinking of designing an ambitious new piece of analog hardware for the studio – what do you know now that you didn’t know before?

Stefan: Well, I’m learning because I’m interested in the success. And by “success,” I don’t mean getting rich from it. I mean that we put so much money, time and effort into it and I want us to — at the end of the day — be able to say that we recouped all that and we created something great.

In the lesson sense, what I’m learning is, “How do you bring something to market? What do you do to increase reach in today’s times?” I would say to everybody who builds analog gear, that creating something good or something that works is not the hardest part.

The hardest part is really defining what your expectations are from it: Do you want to sell one unit, 10 units or a hundred units? After that, do you want to sell more?

I’ve been working with great companies like Dangerous Music for so long that I’m learning how they do things and what their challenges are — I can apply this a little bit to my expectations for Rockruepel. Along the way, I’m learning how to promote and how to get a unit into the market that people are interested in and trying. We’re in that phase, where we’re really exploring everyone who can use it.

Does it make it harder or easier when you’re doing this with gear like the sidechain.one, which is different than what people are used to?

Stefan: It’s hard. It’s tough because even though I think we’ve created something unique, there’s tons of compressors, tons of EQs, out there. Up to the (decade of) the 2000’s, everybody needed analog because everybody had an analog studio. Now that is all different. Some people have decided, “I don’t need any analog gear anymore.” And the ones that are using analog gear, there’s a lot of gear out there which is built exactly like we are — very small runs or custom gear.

It’s a satisfying journey nonetheless. I totally have fun, and we can say we’re working on our next product. It’s going to be something that has not been done yet, and that’s exciting. It’s too early to say anything about it — other than that we’ve started the process of sketching out the circuits on napkins!

— David Weiss is an Editor for SonicScoop.com, and has been covering pro audio developments for over 25 years. He is also the co-author of the music industry’s leading textbook on synch licensing, “Music Supervision, 2nd Edition: The Complete Guide to Selecting Music for Movies, TV, Games & New Media.” Email: david@sonicscoop.com

Please note: When you buy products through links on this page, we may earn an affiliate commission.